Increasing the minimum wage will boost the take home pay of over 1 million workers – but not if the Legislature stalls

To read a PDF version of this report, click here.

Increasing New Jersey’s minimum wage to $15 an hour by 2023 would boost the incomes of over 1 million workers and inject $3.9 billion into the state’s economy.[1] Raising the wage for all workers without significant delay is critically important to improving the economic conditions of families, businesses, and the state at large. While many believe that the state’s economy is stronger due to the reduced rate of unemployment – which has finally dropped below pre-recession levels – poverty still remains concerningly high, signaling a wage problem for low-income workers who aren’t paid enough to purchase their basic day-to-day needs.

Considering that lawmakers passed $15 minimum wage legislation that was inclusive of all workers in 2016, it is surprising and disappointing to see that – eight months into a new administration that supports raising the wage for all – a bill still hasn’t been introduced. There have been murmurs of extending the phase-in period beyond five years, leaving the tipped wage at its current paltry level of $2.13 per hour, and dividing the working class by excluding youth, seasonal, and farm workers from the increase. In an age where the federal government is actively attacking the economic security of the working class, it would be a terrible mistake for lawmakers to raise the wage but leave behind some of the state’s most vulnerable workers.

New Jersey’s recovery from the Great Recession has been one of the slowest and least robust in the nation. As we move further away from that economic crisis, it has become clear that even though the economy shows signs of increasing strength – unemployment levels lower than pre-recession levels, a booming stock market, and healthy GDP growth – the gains of the recovery have been funneled almost exclusively to the already wealthy and well-to-do. Wages have remained stagnant and low- and middle-income families continue to struggle to get by.

A recent survey by the Federal Reserve found that 40 percent of Americans cannot afford– or would have to sell possessions to cover the cost of – a surprise $400 expense. One in five adults say they can’t pay all of their current monthly bills. More than one in four adults report that they’ve forgone important medical care because they can’t afford it.[2] With such a significant share of the workforce still suffering from economic insecurity on a daily basis, it should be no surprise to anyone that inequality continues to grow as our economy lags behind the rest of the country. One can assume that the problem is broader and deeper in high-cost New Jersey.

Contrary to popular belief, the slow growth in wages and the consistent presence of higher poverty levels also has implications for the business community. Oftentimes, businesses don’t see low wages as a problem that hurts them, but the reality is that our economy is consumer-driven, meaning it relies on consumers (i.e. workers) being able to fulfill their demands and needs. When consumers don’t have the disposable income necessary to be full participants in the economy, that hurts businesses who are deprived of would-be customers.

Taking all of this into consideration, lawmakers should prioritize raising the minimum wage for all workers, and soon. When accounting for the cost of living, New Jersey’s $8.60 minimum wage falls $18.38 short of a living wage, ranking 5th worst in the country.[3] The longer this increase is delayed, the more the value of a $15 hourly wage erodes away and becomes insufficient to address the harmful issues it is meant to. Making sure that the most vulnerable workers in the Garden State are being paid a fair wage for their labor is critical to reducing poverty, reversing growing levels of income inequality, and strengthening our economy.

Opting to leave behind any portion of the workforce – as has been discussed recently by legislators in both houses – is unnecessary and cruel, and doing so fails to make our state stronger or fairer for those who suffer the most every single day. Coming to this conclusion isn’t difficult, all it requires is looking at the facts.

Poverty and Inequality Persist Amidst a Sluggish Recovery

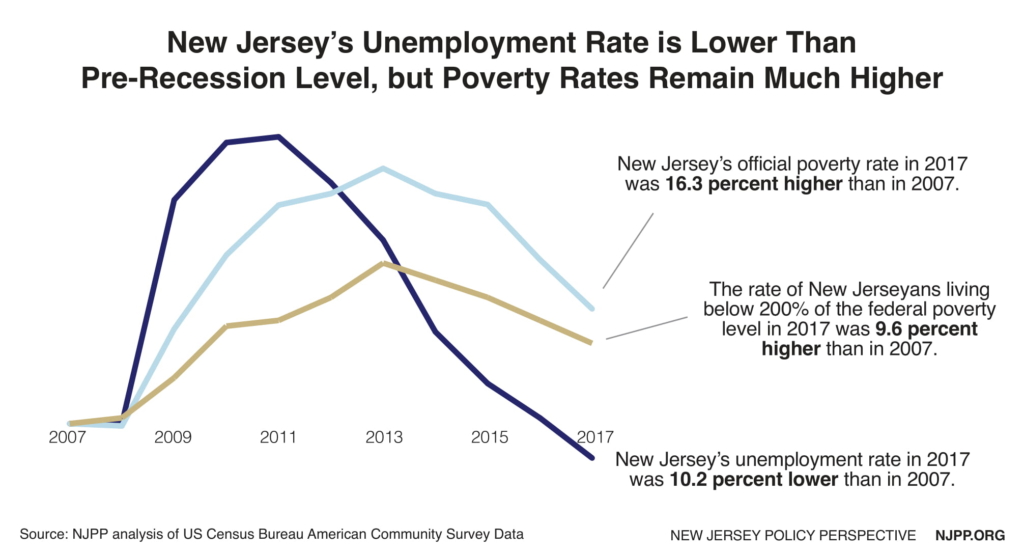

While it is true that unemployment has dropped significantly in recent years – lowering to 5.3 percent in 2017 from 6 percent in 2016 and a high of 10.9 percent in 2011 – poverty rates are higher than they were before the recession. The official poverty rate in 2017 was 10 percent, up from 8.6 percent in 2007 and representing about 143,000 more people. However, considering the high cost of living in New Jersey, the 200 percent federal poverty level provides a more accurate picture of economic insecurity in our state.[4] Looking at this metric, the poverty rate in 2017 was a staggering 22.89 percent, up from 20.89 percent in 2007 and representing about 245,000 more people.

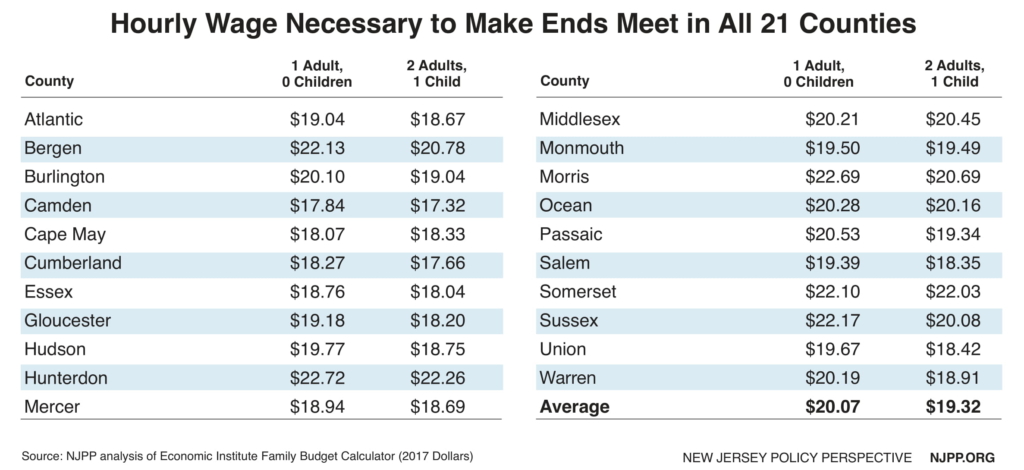

It is not surprising to see poverty remain higher as unemployment decreases considering the minimum wage is far below a livable wage. The Economic Policy Institute (EPI) has a useful tool called the “Family Budget Calculator” which helps measure the income a family needs “in order to attain a modest yet adequate standard of living.” The family budgets that the EPI calculator analyzes consists of seven areas: housing, food, transportation, child care, health care, taxes, and “other necessities” which includes things like clothes, basic household items, and school supplies.

According to EPI’s analysis there is no part of the state where a worker can reliably make ends meet on less than $15 per hour, not even a single adult with no children. For this type of worker, Camden county requires the lowest earnings at $17.84 per hour. Hunterdon County requires the highest earnings at $22.72 per hour. For families with two adults and one child, each parent would have to earn $17.32 per hour in Camden county and $22.26 per hour in Hunterdon County working full time.[5] Looking at the current minimum wage of $8.60, minimum wage workers in each county are earning less than half of what it takes to safely and reliably make ends meet.

As long as a significant portion of New Jersey’s workforce is unable to provide for themselves and their families, the state’s economy will continue to experience widening levels of inequality and sluggish economic growth. Fixing this problem is possible, but only if an increase in the minimum wage to $15 that is fully phased in by 2023 and includes all workers is enacted before the end of the year.

Raising the Wage Would Help a Diverse Array of Workers – Further Carve Outs Should Be Avoided and Youth, Farm and Tipped Workers Must Be Included

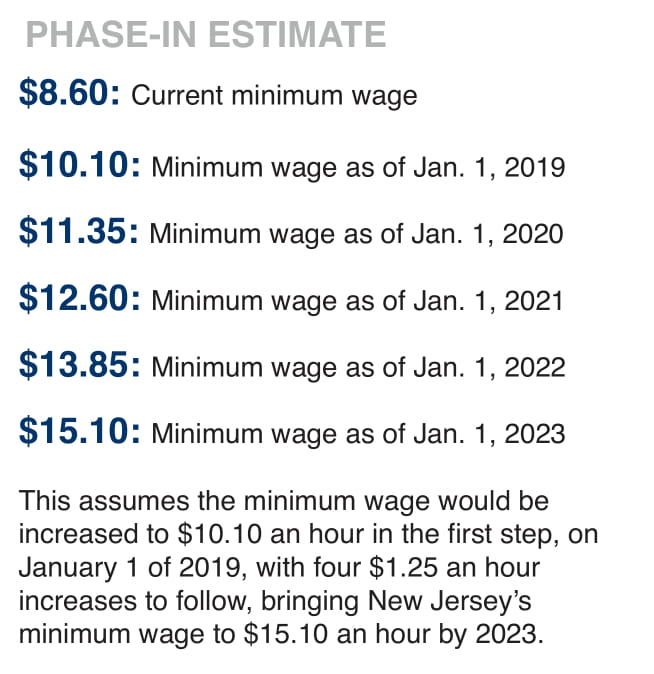

The number of workers who will benefit from increasing the minimum wage to $15 depends on how long the phase-in takes, but we reasonably assume that lawmakers would follow a phase-in schedule similar to the 2016 bill that was vetoed by Governor Christie. As such, we assume that the minimum wage would be increased to $10.10 an hour in the first step, on January 1, 2019, with four annual $1.25 increases to follow, bringing New Jersey’s minimum wage to $15.10 an hour by 2023.

Increasing the minimum wage to $15 by 2023 would result in a $3.9 billion raise for approximately 1,047,000 workers, representing 26.3 percent of the state’s total workforce. Of that group about 792,000 would be directly affected, meaning they currently make less than $14.53 (the current dollar equivalent of $15.10 in 2023). Another 256,000 would be indirectly affected, meaning they make slightly more than the new minimum and would likely see their pay also increase.

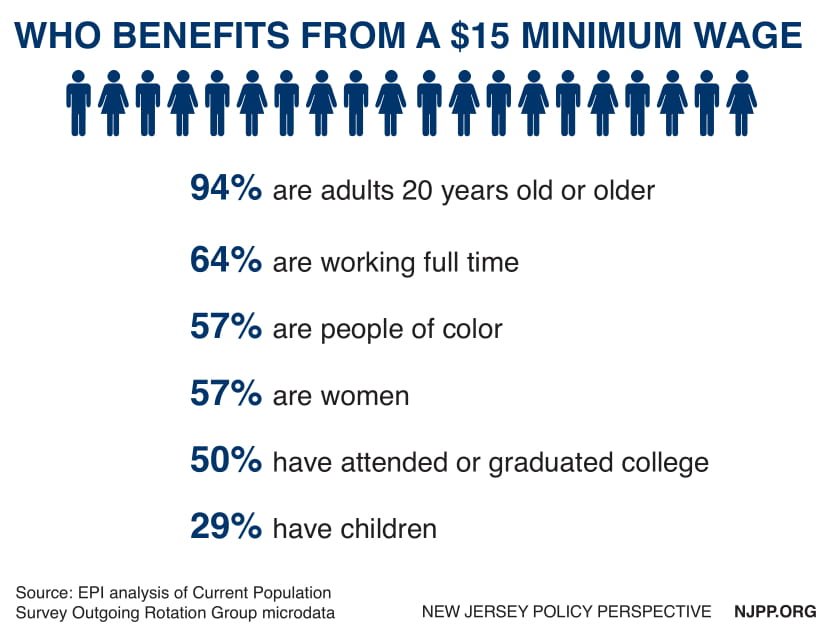

Of those who would benefit, 57.3 percent are women, 57.2 percent are people of color, 94 percent are adults, 29.2 percent have children, 49.7 percent have attended or graduated from college, and 64.3 percent are working full time.

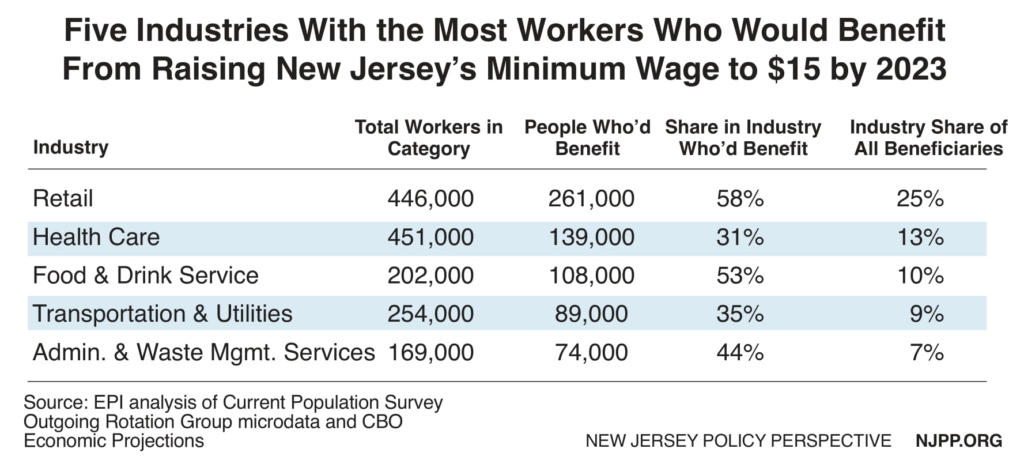

Most of the New Jersey workers who would benefit from increasing the minimum wage to $15 are in the retail, health care, and food service industries.

Existing Exemptions in New Jersey’s Minimum Wage Law

Lawmakers are currently considering carving out youth, farm, and tipped workers from the minimum wage increase. Doing so would be misguided and actively harm these workers, preventing them from earning more for their work and becoming more economically secure. With regard to carve outs, there is a lot of misinformation and misunderstanding on what the current landscape is. There are already several carve outs that exist in New Jersey’s minimum wage law – for youth workers, employees at summer camps, college students, interns, school-to-work programs, tipped workers and farm workers:

- Youth workers (under 18) are currently exempt from the state wage and hour law (see 12:56-3.2). However, the law provides a number of sectors where youth workers are explicitly included in the state minimum wage. Sectors where youth workers are explicitly included in the state minimum wage are: Mercantile occupations (12:57-3); Beauty culture occupations (12:57-4); Laundry, cleaning, and dyeing occupations (12:57-5); Light manufacturing and apparel occupations (12:57-6).

- Employees of summer camps, which often includes many youth workers, are explicitly excluded from the state minimum wage. The minimum wage law is not applicable, “during the months of June, July, August or September of the year to summer camps, conferences and retreats operated by any nonprofit or religious corporation or association,” (34.11-56a4.1).

- Concerning college students and interns, full time students employed by their university or college through a work study program may be paid 85% of the state’s minimum wage (12:56-3.2).

- Interns or participants in “school-to-work” programs, regardless of age, may be excluded from the minimum wage. However, wage and hour regulations provide specific guidelines that must be followed to ensure that education is the primary objective of the position and that any productive labor is incidental to those educational goals (12:56-18).

- Farm workers are currently required to be paid the state minimum wage, but they are not required to be paid overtime for any work over 40 hours per week, including piece work (34:11-5614).

Including as many workers as possible in the minimum wage increase is important to ensure that the most vulnerable workers in the state are better able to make ends meet. It would be wonderful to see lawmakers remove the carve outs that already exist but, at the very worst, they should not add to them.

Youth Workers

Carving out youth workers from a minimum wage increase is bad policy that unnecessarily puts teens at increased risk for poverty and other issues that come with economic insecurity.[6] Of all the workers that would benefit from increasing the minimum wage to $15 by 2023, six percent are under the age of 20, equaling 63,355 total teen workers.

There’s a common stereotype that young workers are simply using their earnings to pay for video games and movie tickets, but that couldn’t be further from the truth for many who are seriously contributing to their family’s income. For teen workers who come from families that earn less than $50,000 per year, they contribute over $9,300 on average, or 18.6 percent. For families of color, teen workers contribute over $9,600 on average, or 19.3 percent.[7] That’s a significant amount and it shouldn’t be discounted. Especially considering that many teen workers in low-income families are saving for the cost of college to help avoid student loans, it would be callous to carve them out from the increase to $15 per hour.

Proposing to carve out teen workers isn’t just a bad idea when you look at the facts, it would also be hypocritical for New Jersey to do so. Just this year, the state passed an equal pay amendment that required women and men to be paid the same amount of money for similar work. To say that pay discrimination against women isn’t ok but pay discrimination against teen workers is would be incredibly hypocritical. Either work is work that should be valued no matter who does it or it isn’t. Lawmakers have already stated that they want to stamp out pay discrimination and they should extend that value to all workers, including teens.

Farm Workers

Some of the most vulnerable workers in the state are farm workers. They are generally people of color and immigrants who perform demanding, physical labor in difficult conditions. Simply put, farm workers are some of the workers that inspired the Fight for $15 movement due to the low wages they earn. Historically, New Jersey has never carved out farm workers from a minimum wage increase before, and to do so now would be an incredible mistake.

An analysis by Professor Michael Reich – an economist and chair of the Center on Wage and Employment Dynamics at the University of California, Berkeley – found that New Jersey’s farm workers would benefit to the tune of a 20 percent increase in annual income.

Many have argued that farm workers must be carved out so that New Jersey can remain competitive in agricultural industries, believing that otherwise the state’s farms would be put at risk of closure. The analysis produced by Professor Reich shows that this opinion is false, concluding that food and produce prices wouldn’t have to increase significantly in order for farms to afford the rise in the minimum wage for their workers. Including farm workers in the increase would result in the price of a package of blueberries increasing just three cents a year annually. That is an incredibly insignificant change that is absolutely worth it to make sure farm workers can be included in the wage increase so they can better meet their needs and provide for their families.

Tipped Workers

New Jersey currently has about 193,000 tipped workers, of whom about 78,000 are waiters or bar staff and all of whom would benefit from increasing the tipped wage which is currently set at the federal level of $2.13 per hour.[8] If a worker doesn’t make the $6.47 in tips necessary to bring them to the state’s $8.60 an hour minimum wage, their employer is required to make up the shortfall – what is known as a “tip credit.” If an employee doesn’t earn enough in tips to make up the difference, the onus is unfortunately on them to ask their employer to bridge the gap – something that many tipped workers are hesitant to do for fear they could risk their job. There is significant evidence to show that tipped workers suffer from higher rates of wage theft than other workers.[9]

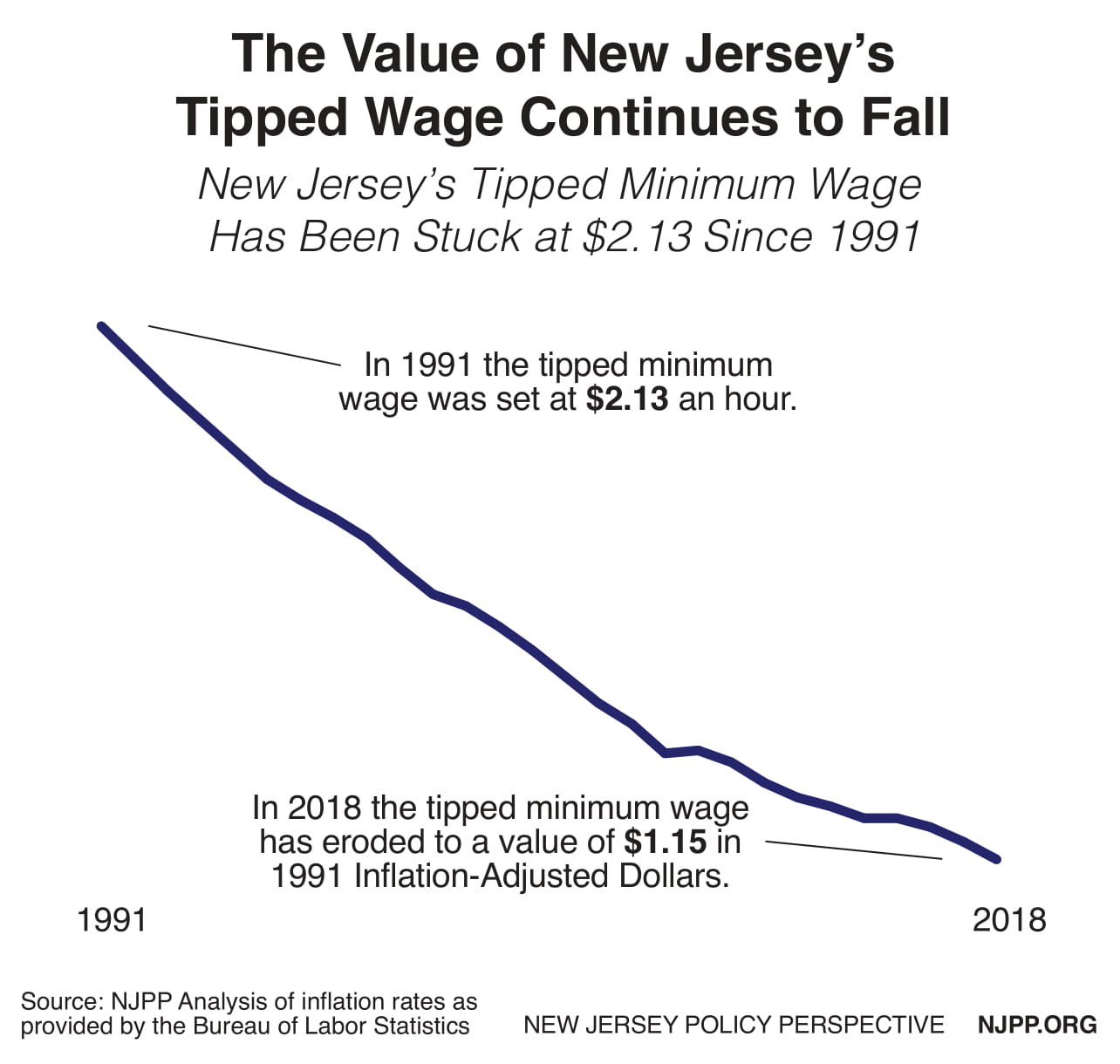

The federal $2.13 tipped wage has remained constant since 1991. Over those 27 years, its value has eroded by 46 percent to a value of just $1.15 in 1991 inflation-adjusted dollars, meaning it would have to be $3.94 in 2018 inflation-adjusted dollars to keep up with 1991’s purchasing power.

The gap between New Jersey’s tipped wage of $2.13 and minimum wage of $8.60 is already one of the largest in the country. To increase the minimum wage to $15 without increasing or completely phasing out the tipped wage would only make that gap larger and invite an increase in instances of wage theft.

Phasing out the tipped minimum wage would be smart policy for New Jersey to pursue. First, it would simplify regulations that owners of tipped businesses have to implement by eliminating the need to calculate wages owed to make up the gap between the tipped wage and the minimum wage. Second, it would make a tip a tip again. Tips would no longer serve as the primary source of income for workers, but represent a slight bonus awarded by the consumer for exceptional service. Besides, seven states – including the entire west coast of the United States – no longer have a tipped wage.[10] Alaska, California, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington have all decided that workers in traditional tipped industries should make at least the minimum wage like every other worker and, despite opposition claims to the contrary, their restaurant and food cultures haven’t become a wasteland of nothing but chain restaurants like Chili’s and Applebee’s.

Getting rid of the tipped wage would have the added benefit of reducing incidents of sexual harassment that female workers face in particular.[11] Because tipped workers are forced to rely on tips to make up the majority of their pay, they end up having to answer whatever whims – fair or otherwise – that customers or their bosses may want. The power dynamics present in these situations put the worker at a disadvantage, and many customers and owners fully exploit it. Phasing out the tipped wage would do away with those power dynamics and let workers focus on their jobs.

The Importance of $15 by 2023 – Further Delay Erodes Purchasing Power

The idea of a $15 minimum wage was introduced four years ago in 2014. Since then, the value of a $15 minimum wage has eroded significantly – $15 in 2014 is worth just $14.08 in 2018. If the original bill had been signed into law when it passed, the state would have reached a $15 minimum wage by 2019. Unfortunately, that didn’t happen, leaving low-wage workers in a lurch. Following recent remarks from legislative leaders that this issue may bleed over into 2019, there is real concern that by the time the wage gets to $15, it won’t be nearly as valuable to low-wage workers as intended.

If the same bill that the legislature passed in 2016 were to be signed this year to take effect in 2019, we would be looking at a scenario where the minimum wage doesn’t reach $15 until 2023. Due to inflation, the delay of 5 years – reaching $15 in 2023 instead of 2019 – adds up to a loss of about 6.5 percent in purchasing power for low-wage workers. In other words, $15 in 2019 would only be worth about $14.02 in 2023, reducing the amount of real income low-wage workers would receive as a result of the policy change from $31,200 a year to $29,161. That’s a loss of over $2,000 in annual earnings for workers and families where every dollar is absolutely critical, and that hurts businesses that are losing out on profits from customers who would have spent that $2,000 locally and immediately. It’s worth noting that these projections don’t take into account changes in current national trade and economic policy that could lead to an increase in inflation, which would result in the value of $15 eroding even further.

If lawmakers hold off passing the $15 minimum wage legislation this year, the erosion from inflation will only significantly reduce what workers ultimately take home. To avoid that affect, it’s worth considering either reducing the phase-in period from 5 years to 4 years or less, or increasing the wage level beyond $15 to make up for lost time, or some combination of the two. The bottom line is that getting to $15 after 2023 dilutes the positive impact of the policy so significantly that simply tying wage increases to inflation after 2023 would be insufficient. Raising the wage to $15 by 2024 – eight years after the Christie veto– and claiming it will address issues of income inequality and poverty would be a dire mistake and a false promise.

While New Jersey Waits, States and Cities Across the Nation Make Progress

In recent years, several states and cities have passed $15 minimum wage legislation in response to the difficult and damaging economic realities that their residents are facing. Seattle voted to increase the wage to $15 in 2014, with the phase-in culminating in 2021 for all workers – employees at large companies started receiving $15 in 2017.[12] Los Angeles voted for its increase in 2015, with all workers receiving $15 by 2020.[13]

In 2016, California passed legislation that would see the state get to $15 by 2022.[14] In the same year, New York signed into law a bill that would increase the wage to $15 for all workers across all industries by approximately 2023 – large business in Manhattan had to get to $15 by 2018 and most workers will reach $15 by 2021.[15]

There are several more places that have voted to increase their wages, but the latest example is Massachusetts, which earlier this year became the third state to vote for a $15 minimum wage.[16] The Bay State opted to get to $15 by 2023, and in doing so included youth workers and increased the tipped wage from 30 percent of the state minimum to 45 percent. It is important to mention that while many view minimum wage increases as a campaign important only to Democrats, the Governor of Massachusetts is a Republican. For their legislation to get to $15 by 2023 and do so without carving out vulnerable workers goes to show that people of all political stripes can understand and support the need for all workers to benefit from this important policy change.

New Jersey is often compared to New York, Massachusetts, and California due to the characteristics we share of being a high-cost state but also having a highly educated workforce, median household income on the upper end of the spectrum, and a diverse population that benefits from vibrant immigrant communities. While New Jersey continues to drag its feet on raising the minimum wage, our contemporaries are moving forward with strength and taking the steps necessary to improve their economies for all of their workers, residents, and businesses.

Beyond economic considerations, there’s significant research to show that increasing the minimum wage helps lead to reductions in recidivism,[17] reductions in domestic violence and child abuse,[18] and reductions in teen pregnancy rates.[19] It is an important determinant of health outcomes and the American Public Health Association notes that income shapes one’s access to other important determinants of health like housing, education, and employment opportunities.[20]

Worries about job losses are belied not only by our own recorded history – when New Jersey last increased the minimum wage through the ballot in 2013 opponents said we’d lose 30,000 jobs[21] and instead we gained 90,000[22] – but also the experiences of business owners in states that have already increased their wage to $15.

Take for instance the story of Tom Douglas, a notable restaurateur in Seattle who owned 15 restaurants prior to the increase and strongly opposed the change, predicting that he would “lose maybe a quarter” of his restaurants in the city. Fast forward to post-increase, more restaurants were opening in the city than in previous years[23] and Douglas himself recanted his previous position as he not only didn’t have to close any restaurants but ended up opening a few new ones. There’s the California fast food CEO who, much like Douglas, thought the increase to $15 would destroy his business but now says it has provided an important boost.[24]

And rigorous research continues to show that increasing the minimum wage is good policy. A new report by the Center on Wage and Employment Dynamics at the University of California, Berkeley, examined the effect of minimum wage increases in six cities – Chicago, Washington, D.C., Oakland, San Francisco, San Jose, and Seattle – and found stronger private sector growth than comparable economies along with no significant negative effect on employment.[25] There’s also a recent report by the U.S. Census Bureau which, looking at 20 years of government- collected data, finds that raising the minimum wage increases worker earnings over the short and long-term without significant declines in employment.[26]

At the end of the day, there are simply too much data and recorded experiences showing that increasing the minimum wage works. For New Jersey to continue to delay action at this point would require ignoring what we know to be true and opting to believe rhetoric and myth over fact and rigorous research. We’ve already suffered significant setbacks, being one of the last states to emerge from the Great Recession, and our economy continues to struggle with poverty rates that are higher than they should be at this stage in our recovery. If we continue to talk about “next year” for increasing the minimum wage to $15, we’ll be left in the dust with no one to blame but ourselves yet again.

The opportunity in front of us is clear – raising the wage will benefit over a million workers, help businesses by providing them with more consumers who can purchase the services and products they offer, and improve the local economy in communities all across the state. There is no reason to hesitate any further, it is time to do what we know is both the right and smart thing to do. It’s time to pass and sign legislation that raises the minimum wage to $15 for all workers, and the time to do it is now.

Endnotes

[1] Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata (2017) and CBO Economic Projections (January 2016)

[2] Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2017, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, May 2018. https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/2017-report-economic-well-being-us-households-201805.pdf

[3] NJPP Analysis of data from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Living Wage Calculator

[4] The official poverty rate – 100% FPL – registers at an annual income of $24,600 for a family of four. In a high cost state like New Jersey, it makes no sense to limit real poverty to such a low level of income.200% FPL is more appropriate and registers at an annual income of $49,200 for a family of four.

[5] Economic Policy Institute, March 2018. Budgets are in 2017 dollars.

[6] National Employment Law Project, Excluding Young New Jersey Workers From A $15 Minimum Wage Is Bad Policy, September 2018. https://www.nelp.org/publication/excluding-young-new-jersey-workers-15-minimum-wage-bad-policy/

[7] National Employment Law Project analysis of U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey Public Use Microdata Sample, 2012-2016

[8] National Employment Law Project analysis of May 2017 Occupational Employment Statistics data.

[9] Economic Policy Institute, Twenty-Three Years and Still Waiting for Change, July 2014. https://www.epi.org/publication/waiting-for-change-tipped-minimum-wage/

[10] New Jersey Policy Perspective Raising the Tipped Minimum Wage Would Increase the Economic Security of Many Hard-Working New Jerseyans, July 2014. https://www.njpp.org/reports/raising-the-tipped-minimum-wage-would-increase-the-economic-security-of-many-hard-working-new-jerseyans

[11] Restaurant Opportunities Center United, Better Wages, Better Tips: Restaurants Flourish With One Fair Wage, February 2018. http://rocunited.org/2018/02/new-report-better-wages-better-tips-restaurants-flourish-one-fair-wage/

[12] Office of the Mayor, Seattle, Washington,$15 Minimum Wage. http://murray.seattle.gov/minimumwage/#sthash.wJiTvFbp.dpbs

[13] Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles’ minimum wage on track to go up to $15 by 2020, May 2015. http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-minimum-wage-hike-20150518-story.html

[14] The Sacramento Bee, Jerry Brown signs $15 minimum wage in California, April 2016. https://www.sacbee.com/news/politics-government/capitol-alert/article69842317.html

[15] New York State, Governor Cuomo Signs $15 Minimum Wage Plan and 12 Week Paid Family Leave Policy into Law, April 2016. https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-cuomo-signs-15-minimum-wage-plan-and-12-week-paid-family-leave-policy-law

[16] National Employment Law Project, Massachusetts Joins New York and California in Adopting $15 Minimum Wage, June 2018. https://www.nelp.org/news-releases/massachusetts-joins-new-york-california-adopting-15-minimum-wage/

[17] Agan, A. Y. and Makowsky, M. D., The Minimum Wage, EITC, and Criminal Recidivism, January 2018. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3097203

[18] Raissian, K. M., Bullinger, L. R.,Money matters: Does the minimum wage affect child maltreatment rates?, January 2017. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0190740916303139?via%3Dihub#!

[19] Bullinger, L. R., The Effect of Minimum Wages on Adolescent Fertility: A Nationwide Analysis, March 2017. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28103069

[20] American Public Health Association, Improving Health by Increasing the Minimum Wage, November 2016. https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2017/01/18/improving-health-by-increasing-minimum-wage

[21] Watchdog, New Jersey’s minimum-wage question poses maximum complexity, October 2013. https://www.watchdog.org/new_jersey/new-jersey-s-minimum-wage-question-poses-maximum-complexity/article_3e1f3a4a-a943-549c-8568-e5639189b72d.html

[22] NJPP analysis of data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. State and Area Employment, Hours, and Earnings, New Jersey, Total Non-Farm, 2013-2015

[23] Puget Sound Business Journal, Apocalypse Not: $15 and the cuts that never came, October 2015. https://www.bizjournals.com/seattle/print-edition/2015/10/23/apocolypse-not-15-and-the-cuts-that-never-came.html

[24] KQED News, Fast Food CEO Says Higher Minimum Wage Boosts Business, January 2017. https://www.kqed.org/news/11245110/minimum-wage-goes-up-and-so-does-business-thats-what-this-fast-food-ceo-says-happened

[25] Allegretto, Godoey, Nadler and Reich, The New Wave of Local Minimum Wage Policies: Evidence from Six Cities, September 2018. http://irle.berkeley.edu/files/2018/09/The-New-Wave-of-Local-Minimum-Wage-Policies.pdf

[26] Rinz, K., Voorheis, J., The Distributional Effects of Minimum Wages: Evidence from Linked Survey and Administrative Data, March 2018. https://www.census.gov/library/working-papers/2018/adrm/carra-wp-2018-02.html