To read a PDF of this report, click here.

After a months-long stalemate, New Jersey’s three most powerful policymakers announced late last Friday that they’d come to an agreement on investing in the state’s transportation networks. As part of the deal, the leaders have agreed to a large-scale package of tax cuts that would disproportionately benefit well-off New Jerseyans while further decimating the state’s ability to pay for essential services, promised obligations and other critical investments.[1]

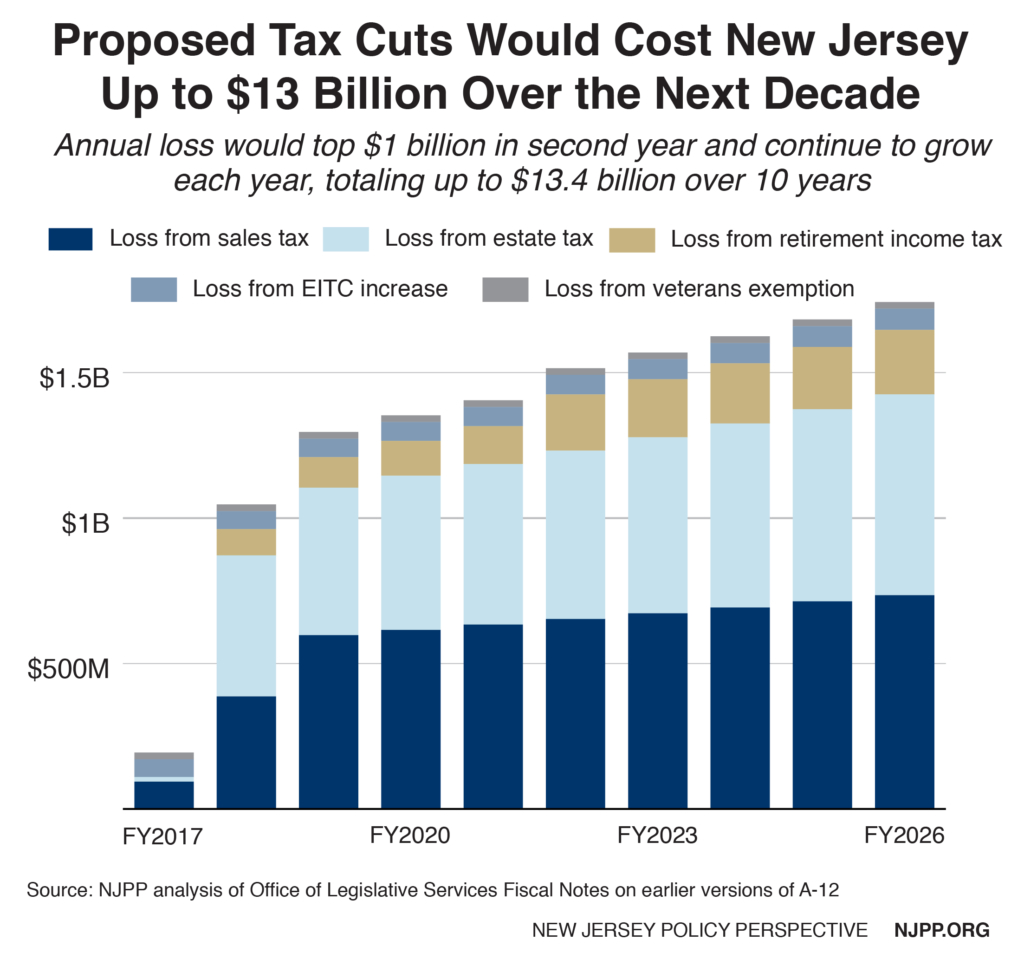

The tax cuts would cost the state approximately $13 billion over the next 10 years, and are the price political leaders are willing to pay as a tradeoff for finally enacting a gas tax increase for essential transportation capital funding over the next 8 years.[2]

At a time when the state already cannot meet its past, current and future obligations; invest in the assets that grow a strong state economy; or provide an adequate safety net for its neediest residents, blowing a hole of this magnitude in the state’s budget is reckless, financially dangerous and – make no doubt about it – unfair.

This projected revenue loss does not include the invisible costs that will almost certainly accumulate quickly as a consequence of yet another round of credit downgrades for New Jersey bond issues, which will produce higher interest rates and tens of millions of dollars in new yearly costs.

Under the proposed plan:

- New Jersey’s sales tax would be cut by 5 percent, to 6.625 percent from 7 percent, over two years, costing about $598 million a year once fully phased in and $735 million a year by 2026

- New Jersey’s estate tax would be completely eliminated over two years, costing about $485 million a year once fully phased in and $690 million a year by 2026

- A tax exemption for retirement income would be expanded by 400 percent over four years to reach higher-income families, costing up to $193 million a year once fully phased in and $221 million a year by 2026

- The state Earned Income Tax Credit would be increased from 30 to 35 percent of the federal credit, costing about $61 million a year to start and $73 million a year by 2026

- A new income tax exemption would be extended to some New Jersey veterans, costing about $23 million a year

These tax cuts would deprive New Jersey of the resources it needs to thrive as a state, from helping to make college affordable to protecting our environment to ensuring that the least fortunate among us have adequate assistance to get by.

But it’s even worse than that.

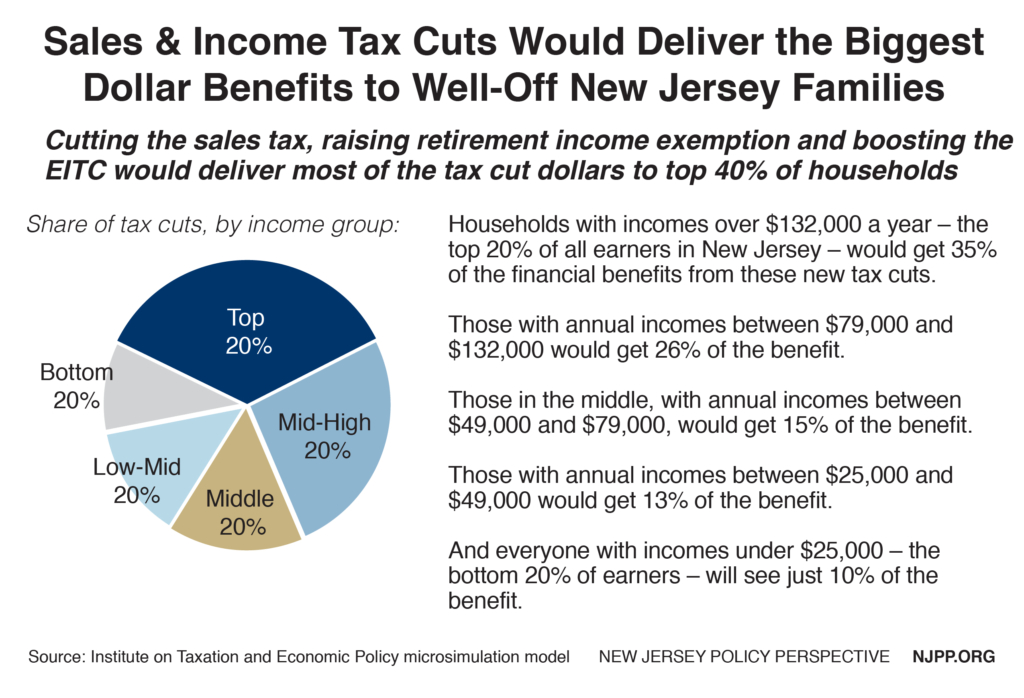

With the exception of the EITC increase – necessary to protect New Jersey’s poorest families from paying the biggest chunks of their earnings to the new fuel taxes[3] – these tax cuts would deliver the most benefit to already well-off families who need it least and guarantee that this tax package fails any reasonable “tax fairness” test.

Estate Tax Elimination Benefits a Fortunate Few

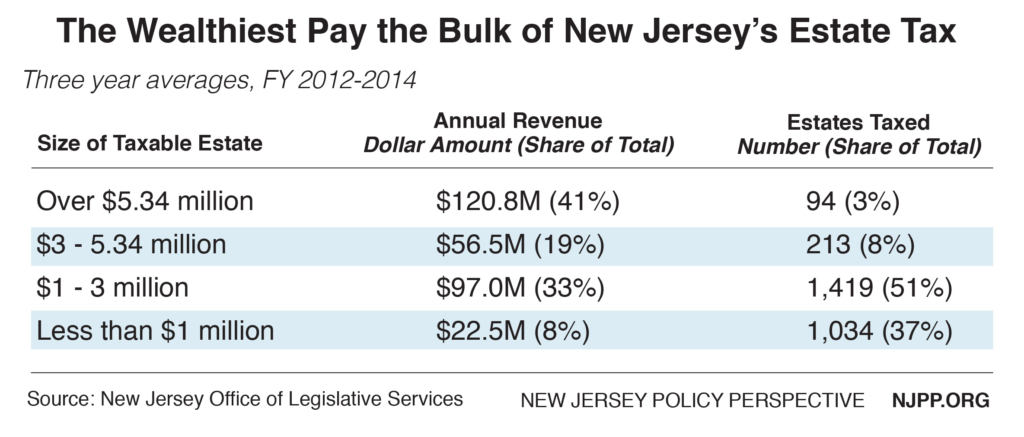

The total elimination of the estate tax, in particular, is incredibly slanted to the wealthiest inheritors of money in the Garden State. In fact, of the approximately 70,000 people who die in New Jersey each year, only about 3,500 – or 5 percent – leave behind estates large enough to owe any estate tax. These estates belong to New Jersey’s wealthiest households.

And fewer than 100 estates – the very largest, each of which has taxable assets of more than $5.34 million – pay 41 percent of estate tax in a given year. Eliminating this tax would give these wealthy families a tax break averaging $1.3 million.[4]

Contrary to the myths about the estate tax, it is clearly not a tax on the state’s middle class. In fact, the median net worth of all Garden State households is $117,000 – and the threshold for filing an estate tax return is five times that amount. Even households at the top – those with the highest 20 percent of assets – have an average net worth of $366,000, still far below $675,000 – the level at which the estate tax kicks in.[5]

While it’s true that New Jersey’s low estate tax threshold makes it an outlier among other states, completely eliminating this tax would make the state an outlier in the other direction. In fact, nearly every other state – plus D.C. – in the wealthy Northeast has an estate tax, as do other prosperous states across the country like Minnesota, Washington and Hawaii.[6]

If policymakers truly wanted to address the state’s outlier status, they would adjust the estate tax rather than completely abolishing it. For example, by raising the threshold to $1 million they could have eliminated the tax for about 2 of every 5 heirs that now owe it, while preserving over 90 percent of the revenue the tax collects.

And while proponents of eliminating the estate tax suggest it must be a top priority to stem the tide of wealth leaving the state, the actual facts flat out debunk the myth of millionaire flight.

We aren’t running out of wealthy New Jerseyans. In fact, we have the fourth highest share of millionaires of all states, and their numbers increased by 11 percent in the last decade. In addition, the number of families with taxable incomes over half a million dollars nearly doubled between 2003 and 2013 – a time including the Great Recession in which income taxes were raised on these folks not once, but twice. Lastly, revenues from the estate tax itself are at an all-time high, and are projected to grow by over 40 percent in just the next five years.[7]

Income and Sales Tax Changes Also Help Well-Off the Most

When looking at the sales tax cut, the retirement exemption expansion and the EITC increase, the fairness picture doesn’t improve much. (The veterans’ exemption is too insignificant to be able to model, and no data exists on the actual earnings of estate tax filers, just their estate sizes.)

In fact, these tax changes would give an average annual cut of $723 a year to the top 1 percent – those with annual household incomes over $808,000 – and an average cut of $76 to those in the bottom 20 percent earning less than $25,000. Those in the middle 20 percent (household incomes between $49,000 and $79,000) would get an average tax cut of $112 a year.[8]

Of course, lower- and middle-income families also have – by definition – less income, so it’s instructive to look at the impact of any tax change as a share of their income. When combined with the fuel tax increases, the sales and income tax changes in this package would make the state’s tax structure less equitable.

Families earning between $25,000 and $49,000 would most feel the pinch, paying 0.17 percent more of their income to taxes each year. And families right in the middle – earning between $49,000 and $79,000 – wouldn’t be far behind, paying 0.13 percent more of their income to taxes each year.

Meanwhile, the top 20 percent of earners – those with incomes above $132,000 a year – would pay just 0.03 percent more of their income to taxes each year. And the top 1 percent, with incomes of $808,000 or more would only pay 0.01 percent more.

Endnotes

[1] New Jersey Governor’s Office, Governor Chris Christie Announces Bipartisan Agreement On Broad-Based Tax Cuts And TTF Funding, September 2016.

[2] NJPP analysis based on two Office of Legislative Services fiscal notes for different versions of the legislation A-12, which included most of the elements in this package: July 2016 (http://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2016/Bills/A0500/12_E1.PDF) and August 2016 (http://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2016/Bills/A0500/12_E2.PDF). For the period beyond OLS’s analysis, NJPP used the following growth projections to determine revenue loss: EITC (2 percent); sales tax (3 percent); retirement income (3.5 percent); estate tax (4.5 percent). This analysis uses the top of a range determined by OLS for revenue loss on the retirement income exemption, and therefore represents a reasonable maximum amount of revenue loss.

[3] New Jersey Policy Perspective, Tax Increase to Fund Transportation Should Be Combined with Credit to Help Low-Income Families, January 2015.

[4] New Jersey Policy Perspective, Eliminating New Jersey’s Estate Tax: Like Robin Hood in Reverse, January 2016.

[5] Corporation for Enterprise Development and Haverman Economic Consulting analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Participation, 2008 Panel, Wave 10, 2013. For more:

[6] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, State Estate Taxes: A Key Tool for Broad Prosperity, May 2016.

[7] New Jersey Policy Perspective, The ‘Exodus’ is More Like a Trickle, June 2016.

[8] Analysis using Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy microsimulation, using 2016 incomes. The analysis is targeted to tax impacts for New Jersey residents only using an estimate that non-residents pay 20 percent of New Jersey sales taxes and 28 percent of fuel taxes.