The COVID-19 pandemic has brought public budgeting into uncharted territory, with states facing shortfalls and an uncertain economic recovery.[i] Making matters more complicated for New Jersey, the state’s budgeting process is an insider’s game that incentivizes politics and short-term decision-making — not good governance or long-term sustainability. Take, for example, the new corporate tax subsidy program. The price tag of this economic development incentive package ballooned from $3 billion to $14.4 billion behind closed doors. This flawed process threatens the future of public schools, health care, and reserve funds for uncertain times. Fortunately, New Jersey can raise the standards of state budgeting by embracing transparency and proven best practices to better face the fiscal challenges at hand.

Improvements that can both de-politicize and more effectively shape New Jersey’s budget include:

- Comprehensive consensus revenue forecasting

- Multi-year forecasting of expected revenue

- Multi-year forecasting of expected spending

- A stronger “Rainy Day Fund”

- Budget “stress tests”

- More transparency in the budget process

Adopting these tools of good governance would raise the level of debate that the current process avoids and, optimistically, would break the cycle of politically easy maneuvers that have contributed to New Jersey’s deep financial hole. This report examines these best practices further and how they can improve New Jersey’s budget process for residents and lawmakers alike.

Comprehensive Consensus Revenue Forecasting

Each year, New Jersey estimates how much money it will collect through taxes, fines, and fees during the upcoming fiscal year. Lawmakers rely on that figure to know how much the state can invest in public goods like education, health care, mass transit, and other services critical to New Jersey’s future prosperity. But the process is inherently politicized, as the executive and legislative branches produce their own competing revenue forecasts.[ii] Disagreements over these estimates often overshadow and distract from important conversations regarding where resources should be allocated and what programs should be prioritized in the budget. In the end, the governor has the authority to determine the official estimates. If the finalized revenue projections are overly confident and inaccurate, it can lead to mid-year budget cuts and accounting gimmicks to keep the budget in balance. If the projections are too low, they can be a barrier to needed investments that the state had the resources to pay for.

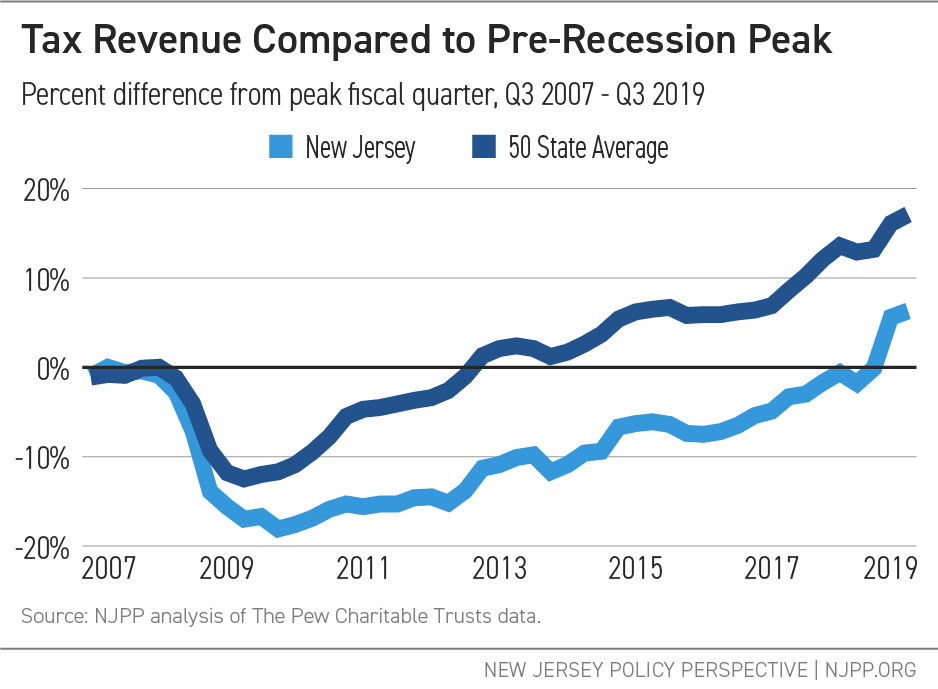

In the years after the Great Recession, the state budget would come up short before the end of the fiscal calendar, leading the administration to find extra dollars with one-time measures such as raiding special revenue funds or postponing payments like property tax relief for senior citizens.[iii] The overreliance on these temporary measures led to large budget shortfalls and several credit downgrades by major credit rating agencies.[iv]

The Legislature, governor, and independent experts such as economists, should instead work jointly to produce a revenue forecast. This type of “consensus” process is employed by more than half of the states (28), helps to reduce the chances of political gridlock, and increases the revenue estimate’s value as a trusted starting point for writing the state budget.[v] It’s also a best practice endorsed by a variety of fiscal policy institutions including the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, the Volcker Alliance, the Urban Institute, and Stockton University’s William J. Hughes Center for Public Policy.[vi]

Consensus revenue forecasting would not only produce a more accurate forecast but also center budget debates on a single revenue estimate for everyone to work from.[vii] This, in turn, would make the budget process more transparent and accessible to the public and Legislature alike, resulting in a more democratic debate and ultimately greater fiscal discipline 一 something bond rating agencies value in their state bonding assessments. A 2015 bill to establish a consensus-forecasting board passed both houses of the Legislature but was ultimately vetoed by Governor Christie.[viii] Recent attempts to put similar legislation on the desk of Governor Murphy have also failed due to conflicting design preferences.[ix]

Overall, the consensus revenue forecasting would be improved by enacting the following changes:

- The revenue estimate should be developed early in the budget process, reviewed periodically, and agreed to by the governor and Legislature. Given New Jersey’s July-June fiscal year, a hypothetical timeline could be: in November, the budget committees and governor agree to a revenue estimate to frame the following year’s budget; in February, the estimate is revisited and revised if necessary; in May, the estimate is reviewed a final time before the budget is passed in June. Throughout this process, the assumptions and documentation behind the estimates would be public and thus subject to inspection and debate by outside stakeholders.

- The revenue estimating body should include outside experts. By including independent economists, along with economic and budgeting experts from state government, lawmakers could further depoliticize the revenue estimate and improve trust in the forecast.

- Revenue forecasting meetings — or at the very least, minutes of the meetings — should be open to the public. This openness can be a marked contrast to states where the estimate is prepared by staff in back rooms or through negotiations among leadership. An open process builds trust among elected officials outside the inner circle who must vote on the budget, as well as the media and the public. They gain access to the information needed to evaluate budget policies based on the facts before decisions are made. Revenue estimating meetings are open to the public or minutes of the meetings are made publicly available in 30 states.[x]

Multi-year Forecasting of Expected Revenue

The pandemic and its long-lasting impact on New Jersey’s economy offer a unique opportunity for lawmakers to move away from short-term and politically convenient budgeting. Instead, they should assess revenue estimates using a long lens, which would allow lawmakers and the public alike to see how changes in tax policy would impact future revenue collections.

While fiscal experts in both the legislature and the Department of the Treasury produce revenue estimates beyond the upcoming fiscal year, there is neither a formal process for coming up with estimates nor an obligation to share them with the public. Projecting how much revenue the state should collect beyond a single year gives lawmakers the ability to anticipate and respond to predictable changes and evaluate newly enacted tax policy over several years. Without the full fiscal picture, budget policy proposals can become fodder for debate based on political potshots rather than credible, impartial information.

Fiscal analysts in the executive or legislative branches may be reluctant to share long-term projections given the potential for forecasting error. To address this apprehension, lawmakers could designate this budgeting best practice as a non-binding planning tool. Even so, a multi-year forecast lessens the chances of unexpected surprises and last-minute tax-cut proposals that rob the state of needed resources in the near-future. So far, 22 states have committed to making longer-term projections for at least three years as part of their budget process.[xi] Ideally, the executive and legislative branches should jointly produce these multi-year estimates to avoid a wasteful and unnecessary political fight over the correct revenue projection.

Multi-year Forecasting of Expected Spending

Projecting what the state spends on programs beyond a single year can provide insight into how to adequately support critical public services over the long-term. This practice can also be used to project the real-world impact of changes in the tax code on specific programs and the communities they serve.

Known as “current services” or “baseline” budgeting, this best practice takes into consideration predictable spending fluctuations, like inflation and per-person costs, expected uptake of services, or scheduled adjustments like the current ramp up toward fully funding both the pension fund and school funding formula. Forecasting in this way provides lawmakers and the public the opportunity to analyze whether a program is meeting expectations given higher operating costs or whether more revenue will be needed to cover a program in the future. Crafting a current services budget does not bind lawmakers to fund the programs and services at the designated levels. This practice simply allows policymakers and the public to better understand the consequences of those funding choices on programs, services, and residents over time.

Currently, 19 states and Washington, D.C. prepare current service estimates beyond the upcoming fiscal year.[xii] Five states publish multi-year projections that provide the cost of current policies in future years and then demonstrate how certain policy changes could affect that cost.[xiii] Transparency is enhanced when current service estimates and its methodology are published alongside the detailed budget, allowing the public, press, and service providers to assess how program cuts or expansions will impact the budget years down the line.

New Jersey should project revenues and current services spending for at least three years to help chart a clear and sustainable fiscal course out of today’s crisis. If New Jersey enacted both current service budgeting and multi-year revenue forecasting, its politicized budget debate could be a thing of the past. High-quality, long-term revenue and expenditure forecasting would shine a light on the underlying structural imbalance between revenue and spending that has chronically held back New Jersey’s economy. Incorporating these forecasting practices would give policymakers the time and the tools to understand the full impact of policy proposals and make course corrections as needed.

A Stronger Rainy Day Fund

Of course, forecasting tools cannot predict economic downturns or when catastrophic events like the coronavirus or climate change disasters hit the state. But building healthy reserves can blunt the damages of these events without having to resort to drastic spending cuts or accounting gimmicks. Despite warnings issued by budget experts over the years, lawmakers have failed to make the emergency fund a priority.[xiv] That lack of planning meant New Jersey’s rainy day fund was near-empty when the COVID-19 pandemic hit and decimated the state’s revenue collections.

New Jersey law dictates how reserves are designated and under what circumstances the state can access them. There are two distinct funds for excess revenue, each with their own rules. The Undesignated Fund Balance is comprised of leftover revenue, or surplus, at the end of the fiscal year. The Surplus Revenue Fund, also known as the “rainy day fund,” is comprised of revenue from better-than-expected tax collections.[xv] Surplus dollars in the Undesignated Fund Balance can be used for any purpose. But money in the rainy day fund can only be “unlocked” under certain circumstances, such as when:

- The governor declares that spending will exceed revenues.

- The Legislature determines that using the fund is preferable to a tax increase to cover a revenue shortfall.

- The governor declares an emergency and notifies the Legislature.

Lawmakers have habitually relied on the fund to balance budgets instead of replenishing the reserves to levels that would buffer New Jersey’s finances against unforeseen emergencies. For example, in the wake of the Great Recession, a cycle of overly optimistic revenue projections resulted in the state not having enough resources to pay for everything included in the budget — let alone having any revenue leftover for reserves. As a result, deposits into the rainy day fund ceased and the fund remained empty for 11 straight years.[xvi] That level of neglect has left the state underprepared for the pandemic as well as the next recession or superstorm. The lack of ample reserves also leaves the state vulnerable to another credit downgrade, which would lead to higher borrowing costs.

Leading up to the pandemic outbreak, most states were better prepared by having more money in an emergency fund than at the start of the Great Recession, both in nominal terms and as a percentage of state expenditures.[xvii] Guided by lessons learned during the Great Recession, these states made deliberate policy changes to deposit rules and other mechanisms of their reserve funds to further strengthen their rainy day fund balances.

With new sources of sustainable revenue and stabilized economy, the Murphy administration has tripled the state’s surplus and was on schedule to make a second deposit into the rainy day fund, building upon FY 2020 $401 million deposit.[xviii] But it’s just a fraction of what should have been put into savings compared to the rest of the country. Since FY 2010, the national median rainy day fund balance as a percentage of general fund spending grew from 1.6 percent to 7.8 percent in FY 2020, a new all-time high due to improved revenue conditions.[xix] In the same period, New Jersey’s rainy day fund balance grew from 0 percent to 1.8 percent.[xx]

Finally, New Jersey can’t allow reserves to be treated like a slush fund or a second-tier obligation. To address this, a change to statutory language should be made to mandate a replenishment schedule with deposit targets based on revenue forecasts.

Budget “Stress Tests”

To better plan for potential economic downturns, New Jersey should build regular hypothetical exercises, known as “stress tests,” into the forecasting process. Based on a similar analysis required of banks under the 2010 federal Dodd-Frank Act, stress tests give budget officials the opportunity to develop state-specific responses to drastic revenue shortfalls or sharp increases in spending in response to an emergency.[xxi] Stress tests can also help analyze tax reform proposals and spending approaches by looking at the potential volatility of either. For example, when the state adopts a progressive revenue source that may be volatile, this type of analysis highlights the importance of setting aside some of the revenue from this tax when it brings in more revenue than anticipated.

New Jersey already uses stress testing to analyze the long-term solvency of the public employee pension system.[xxii] Due to the pandemic, revenue declines called into question whether New Jersey would be able to ramp up its annual pension payment. But stress test data convinced the governor and legislative leaders to increase the pension contribution despite a lagging economy.[xxiii] If lawmakers can rely on nonpartisan, data-driven analysis of the pension system, surely they could enact stress testing of state finances as a best practice measure.

Annual stress tests on the state budget are equally important because they give lawmakers guidance on how to recover from multi-year shortfalls and help establish attainable reserve goals. Stress tests are also a smart way to examine turbulent revenue streams, which can inform decisions about how to reduce risky volatility.

A Transparent and Responsive Budget Process

“In difficult fiscal times, legislators and governors can be tempted to forgo best practices and sacrifice fiscal stability for short-term fixes to maintain as many government services as possible. Yet states may find that long-term commitments to improved budget processes will leave them better able to deal with the natural disasters and fiscal crises that inevitably occur.” – The Volcker Alliance, 2018[xxiv]

Recently, the Volcker Alliance graded the transparency of states’ budget documents based on four key disclosure practices.[xxv]They include:

- An accessible website of budget procedures, schedules, and data like reports on unfunded liabilities, capital budgeting, economic forecasting, and reserves.

- Clear, accessible, and detailed tables showing the amount of debt owed by the state and debt service costs.

- A report on the cost of deferred infrastructure maintenance for assets like roads, bridges, and buildings.

- Regular accounting of the cost of tax exemptions, credits, and abatements used to attract or retain economic development and jobs.

Overall, New Jersey received a “B” for following most of these practices, with the exception of disclosing deferred infrastructure maintenance costs.[xxvi] In fact, only three states — Alaska, California, and Tennessee — received an “A” because they prioritize documentation of what needs to be spent in the long-term to keep publicly owned physical assets in good shape. While mandated procedures and reports may look good on paper, New Jersey is failing to maintain meaningful transparency in practice.

On the website of New Jersey’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB), one can find archived state budgets dating back to 1987 and financial information in the Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports (CAFR) going back to 2002.[xxvii] A budget lays out the annual spending plan using tax income and other revenue and a CAFR reveals the state’s overall financial condition. Budgets are intentions, CAFRs are detailed financial evaluations. However, the various access points and static nature of the documents hardly translates to a level of transparency that could convey a full picture of the state’s fiscal stability. This kind of convoluted disclosure makes policymakers blind to the impact of their budgeting decisions or, worse, allows decisions to be driven by politics rather than good budgeting practices. The Department of Treasury ought to produce a more accessible and interactive online archive of these documents as well as the annual Debt Reports and mandated report on New Jersey’s tax credit programs, the Unified Economic Development Budget.

Transparency in the state budget process itself is just as important as crafting a sustainable one. Unlike the governor’s budget, which is mandated to be released by a certain date, the Legislature’s proposal is not subject to a timeline. The result is a vacuum whereby leadership crafts a deal behind closed doors and releases a budget just days, and sometimes hours, before it must be voted on and signed into law. This ad hoc process has become so commonplace, it is practically treated as a normal course of action. But, in reality, it removes meaningful analysis and debate about the most consequential legislation of the year. Placing sunshine on the final stage of resolving differences could put an end to the habit of bypassing public scrutiny.

Finally, providing clear and easily accessible information can help the public better understand the scope of New Jersey’s responsibilities and challenges and guide policymakers to make better-informed decisions about how to allocate resources. Lawmakers could improve access to budget documents in the following ways:

- Consolidate disclosure documents in an interactive format to better track budgetary needs and challenges. These should include data on revenue volatility, deferrals of spending, long-term obligations, and spending and revenue trends and forecasts.

- Establish a uniform format design of the state budget documents to improve searchability for research purposes.

- Mandate a publication date for the legislature’s proposed budget and establish a timely process to allow for a more inclusive public debate in the final weeks before budgets are signed into law.

Better Budgets Can Pave the Way to a Better Future

Striving for the best possible information about a state’s fiscal health is the key ingredient to a productive debate about annual and long-term policy priorities. Taken together, these proven budget methods provide a more complete picture of the real costs of obligations and investments and the resources necessary to fund them. They may not guarantee better outcomes by themselves, but these proven budgeting practices can reduce uncertainty and improve policymakers’ ability to plan for the future.

Endnotes

[i] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, States Grappling with Hit to Tax Collections, August 2020. https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/states-grappling-with-hit-to-tax-collections

[ii]The Legislature’s Office of Legislative Services provides revenue estimates for its members. The administration’s Office of the Chief Economist, Office of Revenue and Economic Analysis, and Office of Management and Budget collaborate to provide revenue estimates for the governor. Official revenue estimates are made for both the current fiscal year and the budget fiscal year. The governor formally certifies the revenue estimates per the New Jersey State Constitution.

[iii] NJ Spotlight, Raids on Dedicated Funds Climb Under Christie, July 2013. https://www.njspotlight.com/2013/07/13-07-08-raids-on-dedicated-funds-climb-under-christie/; NJ Spotlight, A Look at the Fuzzy Math of NJ’s Homestead Tax-Relief Program, September 2019. https://www.njspotlight.com/2019/09/a-look-at-the-fuzzy-math-of-njs-homestead-tax-relief-program/

[iv] Reuters, New Jersey credit rating cut for 11th time under Christie, March 2017. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-new-jersey-downgrade-moody-s/new-jersey-credit-rating-cut-for-11th-time-under-christie-idUSKBN16Y2LF

[v] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Improving State Revenue Forecasting: Best Practices for a More Trusted and Reliable Revenue Estimate, September 2014.https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/improving-state-revenue-forecasting-best-practices-for-a-more-trusted?fa=view&id=4185

[vi]Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Improving State Revenue Forecasting: Best Practices for a More Trusted and Reliable Revenue Estimate, September 2014.https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/improving-state-revenue-forecasting-best-practices-for-a-more-trusted?fa=view&id=4185; The Volcker Alliance, Truth and Integrity in State Budgeting: Preventing the Next Fiscal Crisis, December 2018. https://www.volckeralliance.org/truth-and-integrity-state-budgeting-preventing-next-fiscal-crisis; Stockton University William J. Hughes Center for Public Policy, State Revenue Forecasts: Building a Shared Reality,February 2017. https://stockton.edu/hughes-center/documents/2017-0203-state-revenue-forecasts.pdf

[vii] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Improving State Revenue Forecasting: Best Practices for a More Trusted and Reliable Revenue Estimate, September 2014.https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/improving-state-revenue-forecasting-best-practices-for-a-more-trusted?fa=view&id=4185

[viii] New Jersey Bill No. A4326/S2942 https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2014/Bills/A4500/4326_R1.PDF

[ix] NJ Spotlight, Could Advisory Board Health NJ Avoid Last-Minute Budget Shortfalls?, December 2018. https://www.njspotlight.com/2018/12/18-12-12-could-advisory-board-to-forecast-annual-budget-help-avoid-last-minute-shortfalls/

[x] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Improving State Revenue Forecasting: Best Practices for a More Trusted and Reliable Revenue Estimate, September 2014.https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/improving-state-revenue-forecasting-best-practices-for-a-more-trusted?fa=view&id=4185

[xi] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Better State Budget Planning Can Help Build Healthier Economies, October 2015. https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/better-state-budget-planning-can-help-build-healthier-economies

[xii] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Better State Budget Planning Can Help Build Healthier Economies, October 2015. https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/better-state-budget-planning-can-help-build-healthier-economies#_ftn10

[xiii] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Better State Budget Planning Can Help Build Healthier Economies, October 2015. https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/better-state-budget-planning-can-help-build-healthier-economies#_ftn10

[xiv] NJ Spotlight, How We Got Here: New Jersey’s Long Record of Not Putting Enough Money by for a Rainy Day, June, 2020.https://www.njspotlight.com/2020/06/how-we-got-here-new-jerseys-long-long-record-of-not-putting-enough-money-by-for-a-rainy-day/

[xv] New Jersey Treasure, Office of Management and Budget, State Financial Policies: Basis of Budgeting. https://www.nj.gov/treasury/omb/policies.shtml (last updated May 5, 2020)

[xvi] The Pew Charitable Trusts, States’ Financial Reserves Hit Record Highs, March 2020. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2020/03/18/states-financial-reserves-hit-record-highs

[xvii] The Pew Charitable Trusts, Rainy Day Funds Help States Weather Fiscal Downturns, April 2020. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2020/04/09/rainy-day-funds-help-states-weather-fiscal-downturns

[xviii] New Jersey Treasury Department, Testimony of State Treasurer Elizabeth Maher Muoio Before Assembly Budget Committee Hearing, May 28, 2020. https://www.state.nj.us/treasury/news/2020/05282020.shtml

[xix] National Association of State Budget Officers, Fiscal Survey of the States: Spring 2020, June 2020. https://www.nasbo.org/reports-data/fiscal-survey-of-states

[xx] National Association of State Budget Officers, Fiscal Survey of the States: Spring 2020, June 2020. https://www.nasbo.org/reports-data/fiscal-survey-of-states

[xxi] The Pew Charitable Trusts, Rainy Day Funds Help States Weather Fiscal Downturns, April 2020. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2020/04/09/rainy-day-funds-help-states-weather-fiscal-downturns

[xxii] The Pew Charitable Trusts, New Jersey to Make Largest Pension Contribution in State History, October 2020. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2020/10/01/new-jersey-to-make-largest-pension-contribution-in-state-history

[xxiii] The Pew Charitable Trusts, New Jersey to Make Largest Pension Contribution in State History, October 2020. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2020/10/01/new-jersey-to-make-largest-pension-contribution-in-state-history

[xxiv] The Volcker Alliance,Truth and Integrity in State Budgeting: Preventing the Next Fiscal Crisis, December 2018. https://www.volckeralliance.org/truth-and-integrity-state-budgeting-preventing-next-fiscal-crisis

[xxv] The Volcker Alliance,Truth and Integrity in State Budgeting: Preventing the Next Fiscal Crisis, December 2018. https://www.volckeralliance.org/truth-and-integrity-state-budgeting-preventing-next-fiscal-crisis

[xxvi] The Volcker Alliance, State Budget Practice Report Cards and Budget Resource Guide: New Jersey, 2020. https://www.volckeralliance.org/sites/default/files/Volcker%20Alliance-StateBudgetingReport-Tearsheet-NewJersey-FY17-19.pdf

[xxvii] New Jersey Treasury Department, Office of Management and Budget, Publications. https://www.nj.gov/treasury/omb/index.shtml#currentpubs