New Jersey is stronger when people of varied backgrounds, experiences, and perspectives work and learn together. For the state’s public education system, teachers and leaders of color play critical roles in ensuring equity. However, people of color are decreasingly represented in the teaching workforce. This problem is particularly acute in Camden, New Jersey, where the city now employs fewer Black teachers and more white teachers than it did two decades ago. The decline in Black teachers is largely attributed to charter and renaissance school expansion, where charters are hiring fewer teachers of color. This expansion has also resulted in a less experienced workforce, as charter and renaissance teachers have far less experience than Camden City School District teachers. While this is a major workforce equity problem, this is also a problem for students, as students of color benefit from having access to teachers of their race. This brief examines Camden schools, charter expansion, and the resulting shift of the whitening of Camden teachers.

Background: Camden’s Schools, Charter Expansion, and State Control

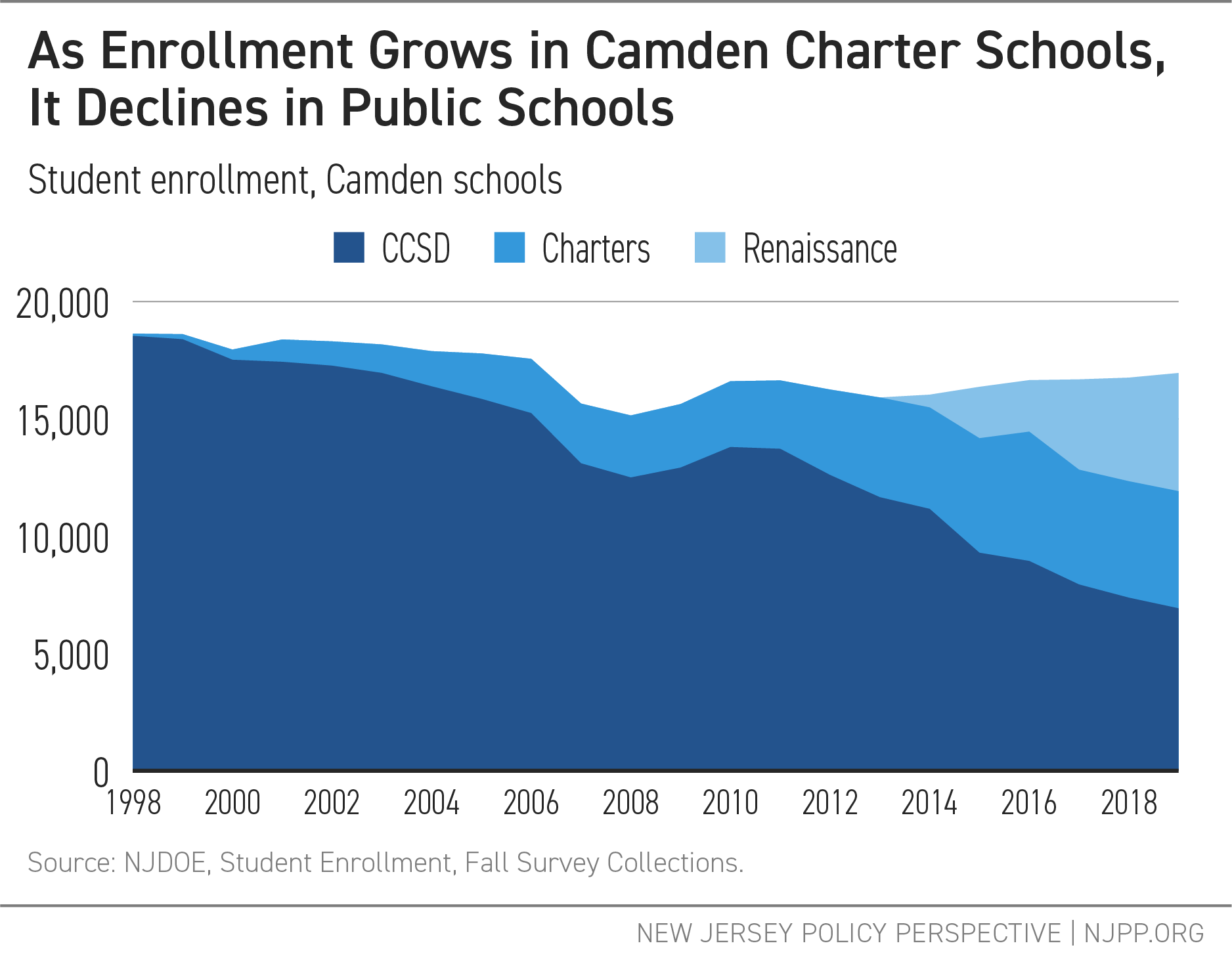

Recent reports of the likely closing of several schools in the Camden City School District (CCSD) will come as no surprise to anyone who has observed the city’s educational system over the past two decades.[1] Enrollment in CCSD has been declining for years, even as the overall population of students in publicly funded schools has changed little. Instead, and like other cities in New Jersey, CCSD has seen its enrollments drop due to the rapid growth of charter schools: publicly funded schools approved directly by the state and run by private, non-governmental organizations.

Camden’s charter sector, however, is unique: many of its students are enrolled in “renaissance” schools, a special type of charter school authorized by separate legislation that receives additional financial support.[2] Renaissance schools were introduced to Camden with the promise from their supporters that they would enroll all students within their given boundaries or “catchments.”[3] A State Auditor’s report in 2019, however, found that the renaissance schools were enrolling many students outside their catchments, even as students within them were put on waitlists.[4]

Renaissance and other charter school enrollments have become more prevalent in Camden over the last two decades. While the overall number of students in publicly funded schools has declined by less than one thousand students since 2000, the growth in charter and renaissance enrollments has left CCSD with 10,592 fewer students over the same period.

Changes in Camden’s Teacher Workforce: Less Diversity, Less Experience

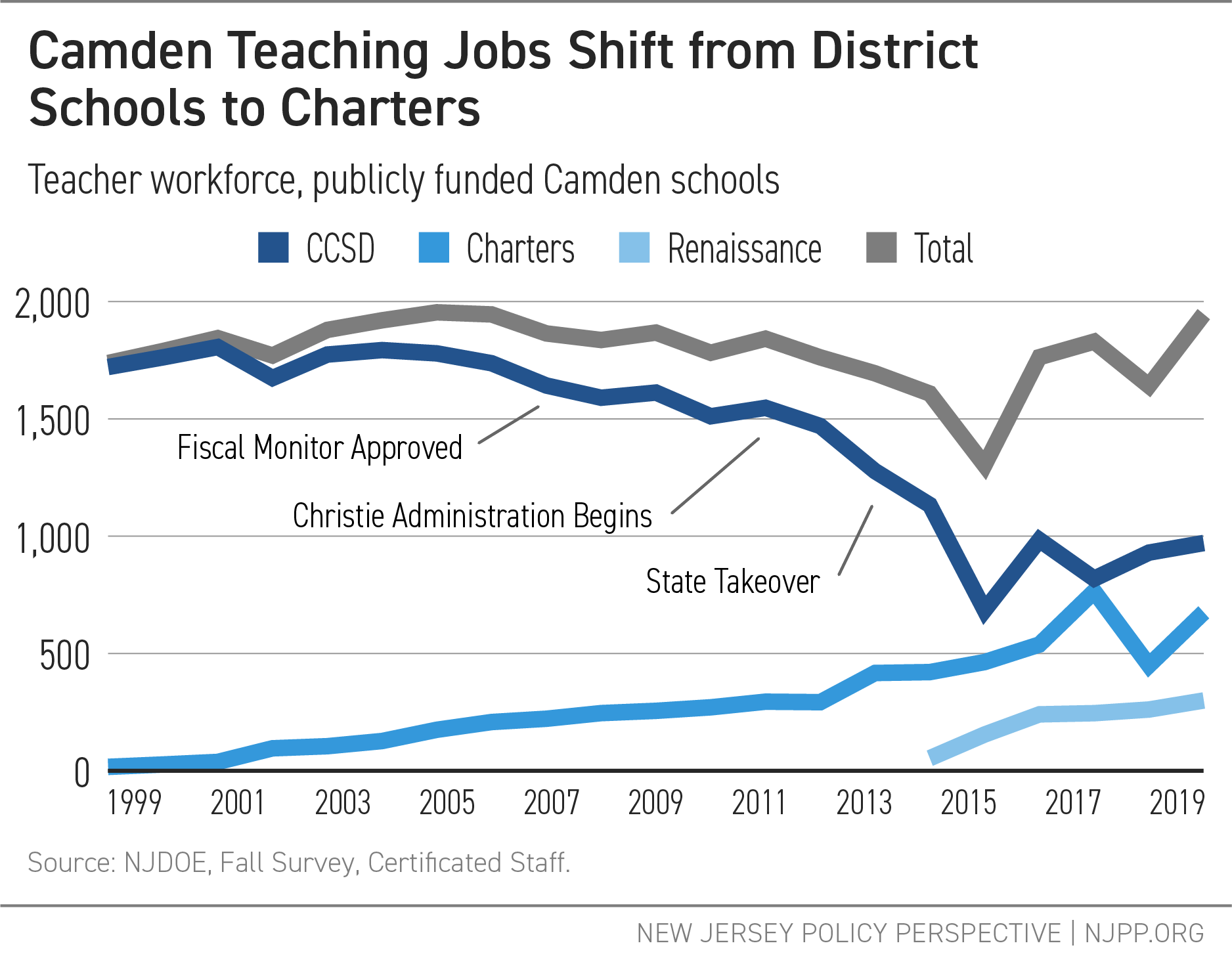

While there are several important consequences to the shift in enrollments from CCSD to charter and renaissance schools, one that is not often discussed is the change in the composition of the teacher workforce in Camden.[5] As CCSD enrollments have declined and charter/renaissance enrollments have increased, teaching positions in CCSD have been replaced by positions in charter/renaissance schools.

It is important to note that the decline in CCSD teaching positions preceded the state takeover of the district in 2013,[6] the year before the city’s first renaissance schools opened. Most of the decline occurred after 2006, when the state first appointed a fiscal monitor—who oversees and approves all operation, management, and staffing decisions— for the district.[7] The decline accelerated during the early years of the Christie administration; Governor Christie was well-known as a supporter of charter school expansion.[8]

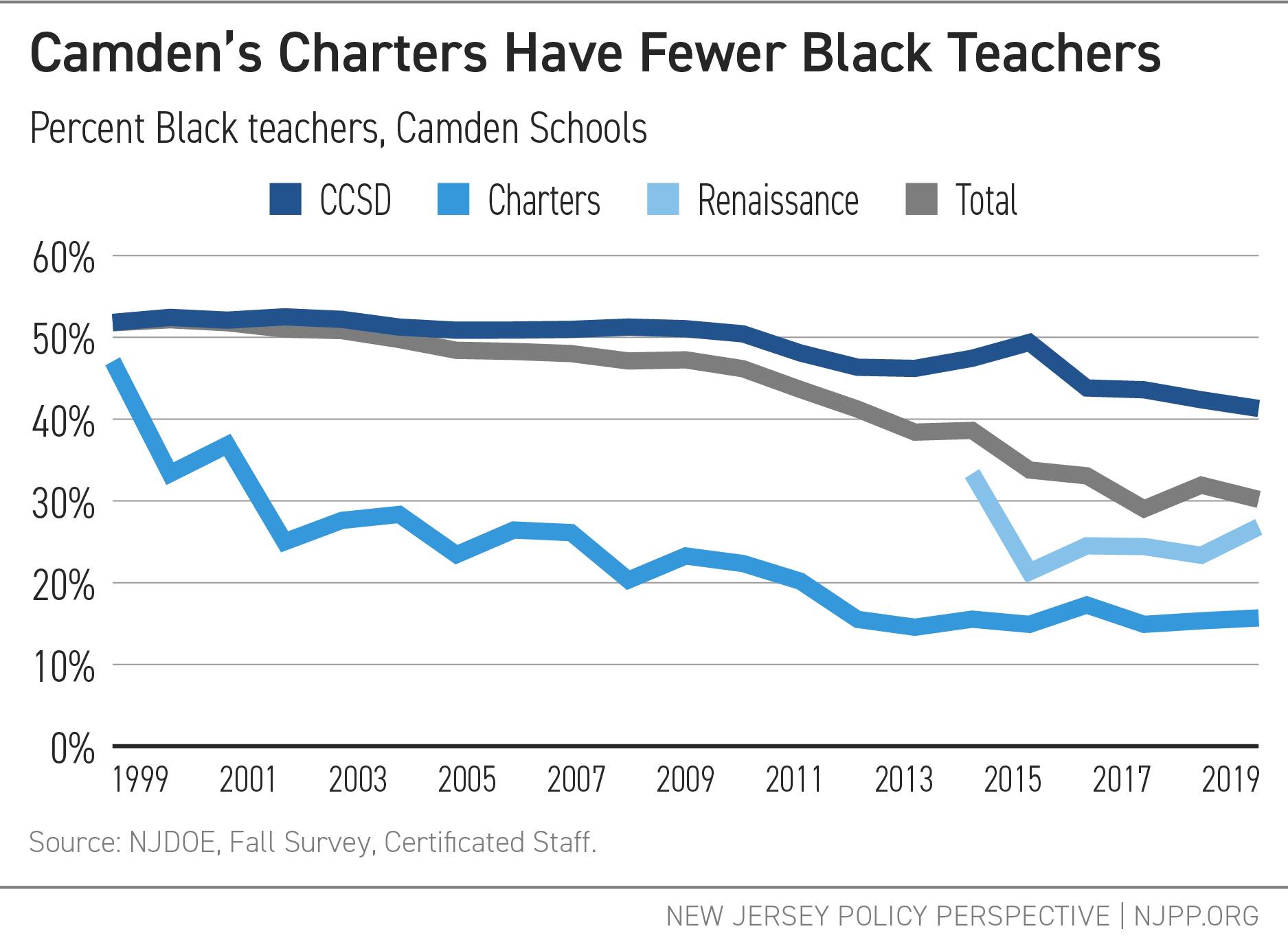

The demographic composition of the CCSD teaching workforce is considerably different from the charter/renaissance workforce: charter teachers are less experienced and less likely to be Black. While the percentage of Black teachers in CCSD has declined in the last decade, it has always been higher than the same percentage in the charter/renaissance schools.

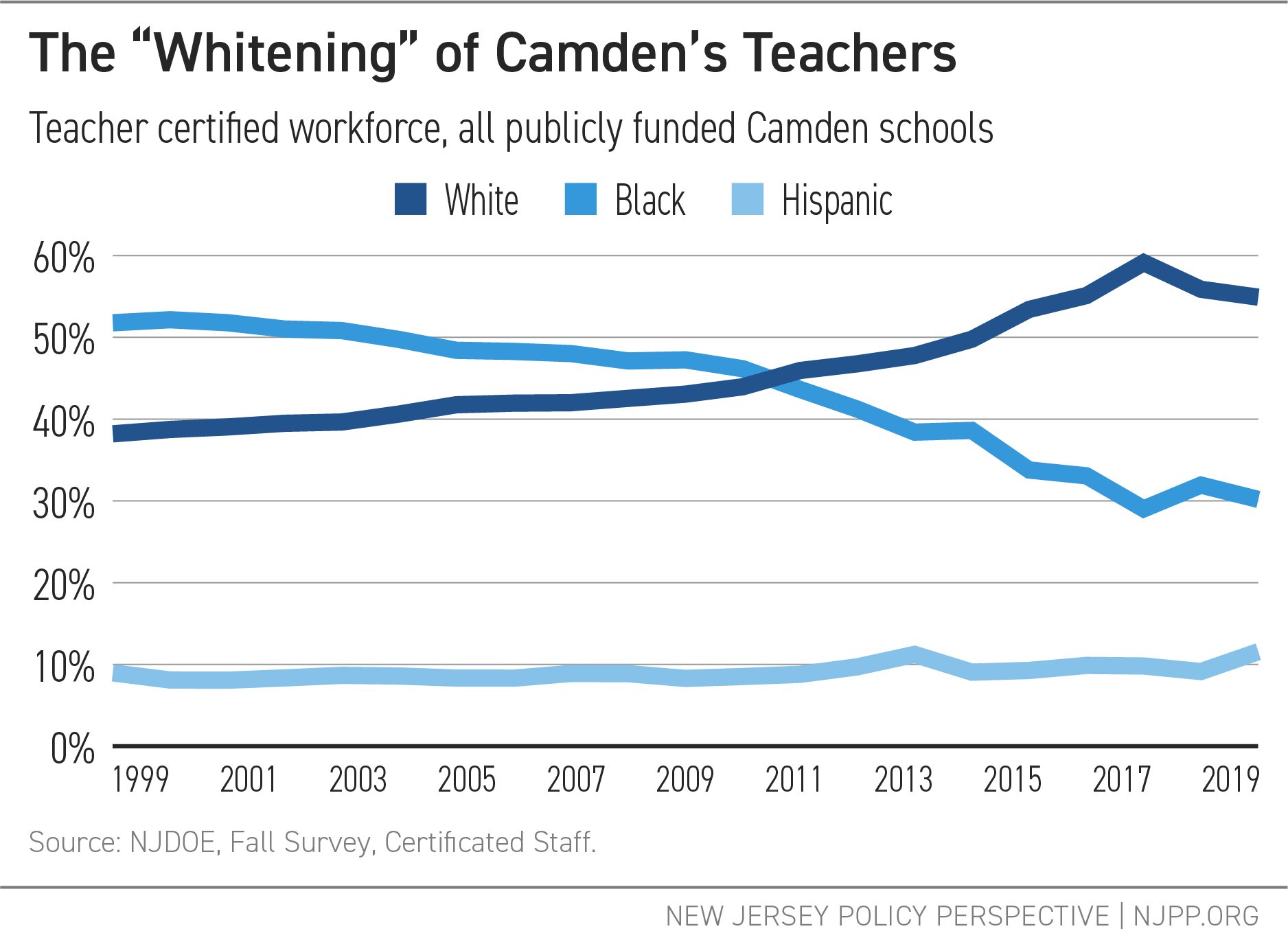

These two factors—fewer Black teachers in CCDS and a shift to more charter/renaissance teachers—have greatly impacted the overall Camden teaching workforce. Two decades ago, the majority of Camden’s teachers were Black; today, the majority are white.

In 1999, 52 percent of Camden’s teachers were Black; by 2019, only 30 percent were. In contrast, 38 percent of Camden’s teachers were white in 1999; 55 percent were in 2019. Changes in the percentage of Hispanic/Latinx teachers or of other races do not explain this remarkable shift. [9]

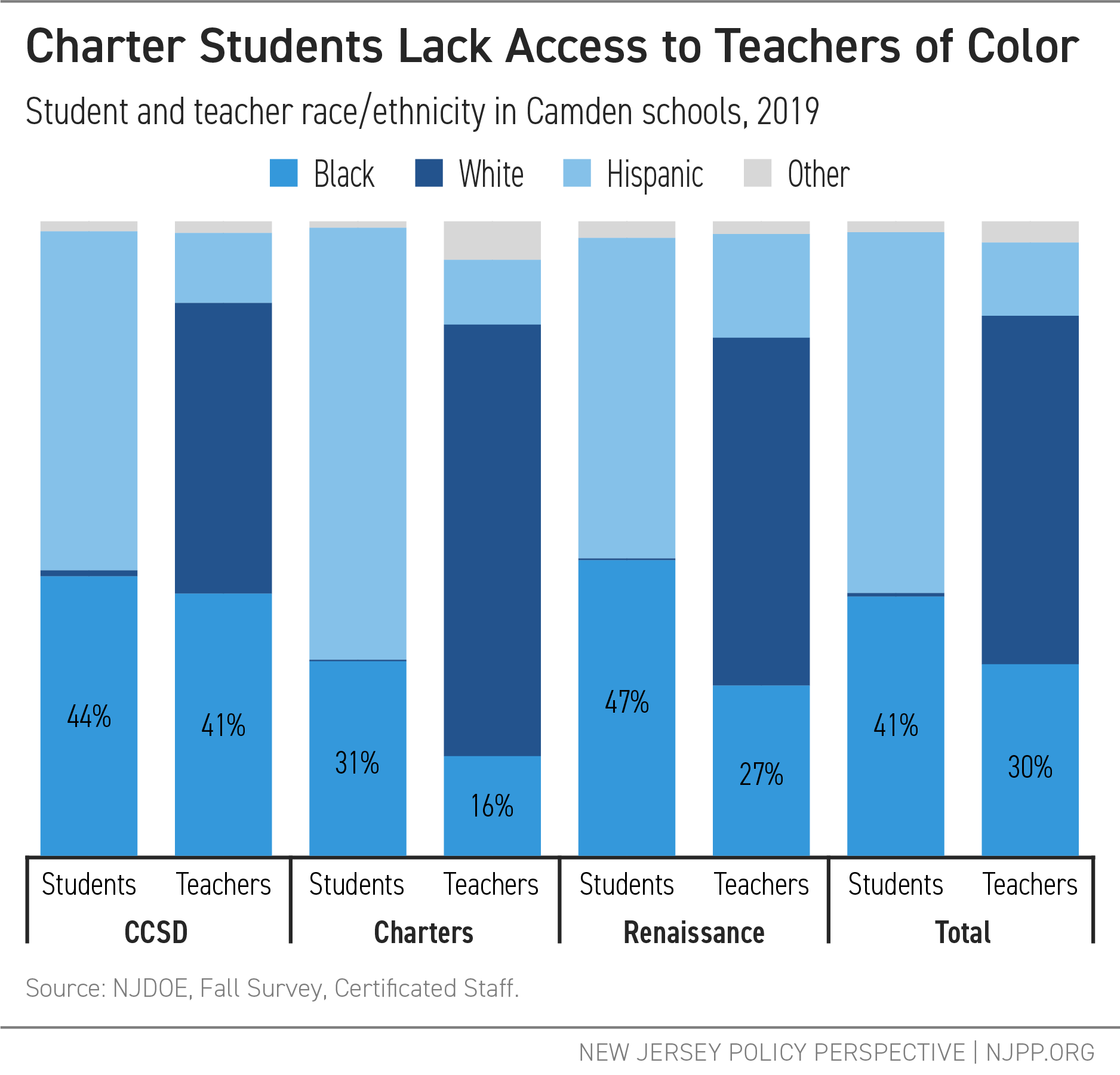

The changes in the Camden teacher workforce’s racial/ethnic profile have left Camden’s students with fewer teachers who look like them. In CCSD, 44 percent of students and 41 percent of teachers are Black. In charter schools, however, 31 percent of students are Black, but only 16 percent of teachers are. Similarly, 47 percent of renaissance students are Black, but only 27 percent of teachers are. The shift in the teacher workforce from CCSD to charter/renaissance schools, therefore, creates a greater racial mismatch between students and teachers across the entire city.

Black students in Camden are not the only students whose identities are underrepresented in the teacher workforce: the proportion of Hispanic/Latinx students in Camden is far greater than the proportion of Hispanic/Latinx teachers. This is true in both CCSD and the city’s charter sector. As NJPP notes in its report on educator training in New Jersey, there are significant barriers to entry for potential teachers of color in teacher preparation programs; the problem of teacher diversity, therefore, is hardly exclusive to Camden.[10]

The mismatch of teacher and student race and ethnicity in Camden has important consequences. As NJPP documents in its latest report on the teacher workforce in New Jersey, students of color benefit from having teachers of their own race in their schools.[11] This benefit has eroded, however, as more teaching positions close in CCSD and open in the charter schools.

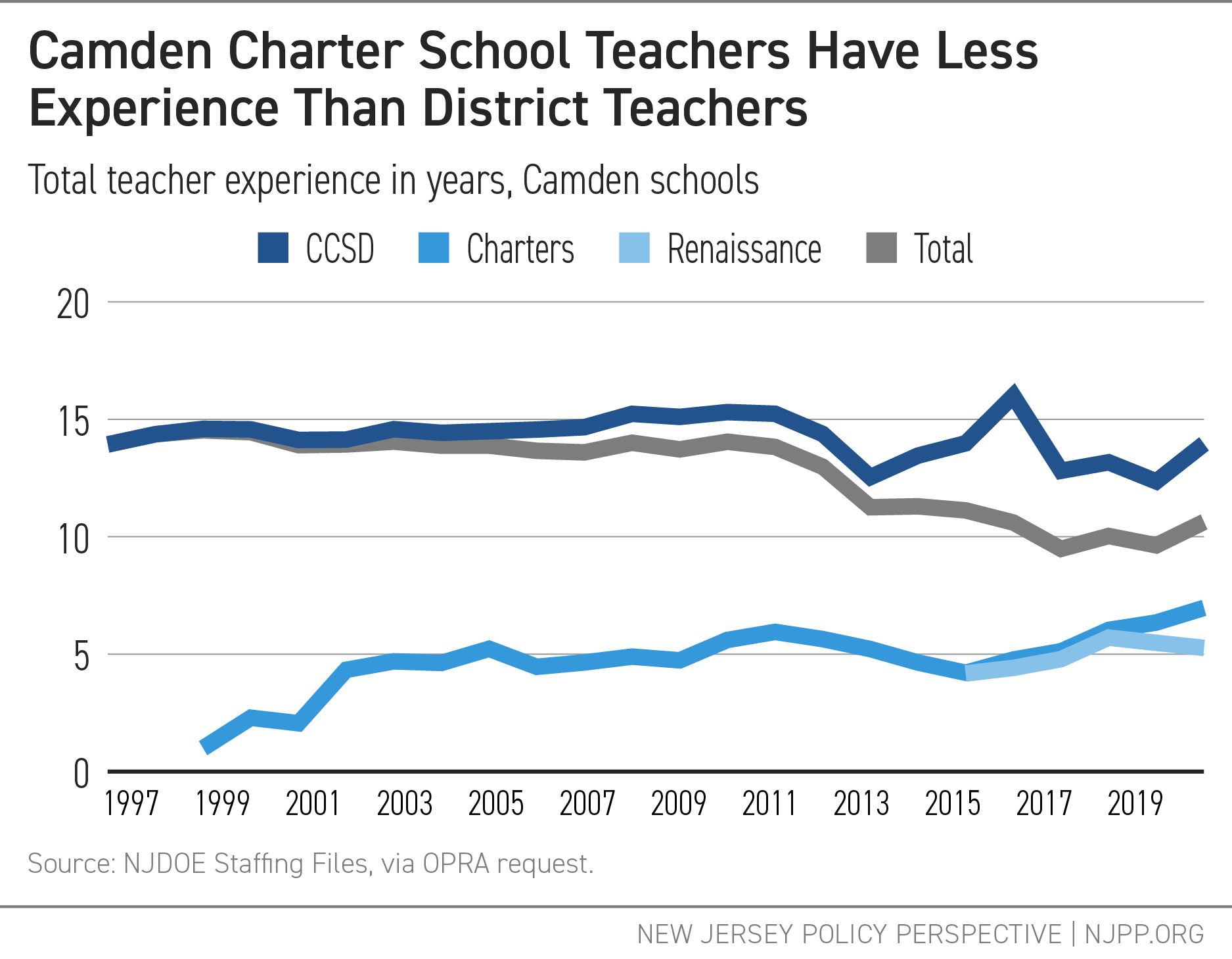

Another notable change in Camden’s teaching workforce is the decrease in average educator experience. A Camden teacher had 14 years of total experience in 1997; today, they have less than 11 years. This change can almost entirely be attributed to the growth of charter schools. Although the average experience of charter and renaissance teachers has gone up slightly in recent years, charter teachers have far less experience on average than CCSD teachers.

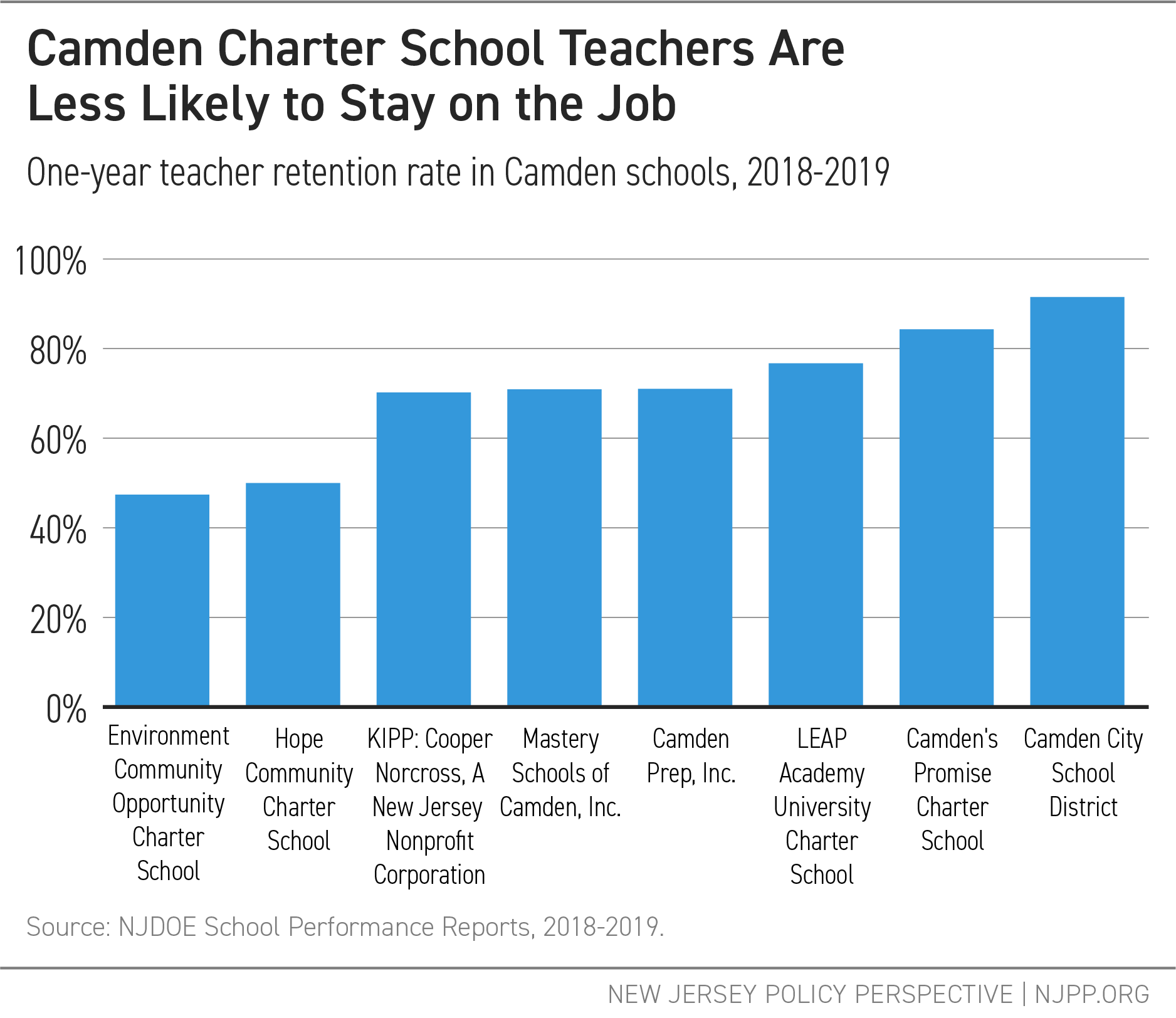

The simplest explanation for charter school teachers’ lack of experience is that the schools do not retain staff nearly as long as CCSD. In the 2018-19 school year, 92 percent of teachers who worked in CCSD in 2017-18 returned. Contrast this with the 70 percent retention rate in the renaissance schools, or even lower rates in some of the charters.

Previous research on New Jersey’s charter sector suggests that some charter operators—including those who operate the renaissance schools—benefit from employing a staffing model that churns teaching staff. [12] Because teachers earn more in their later years, cultivating a less experienced staff allows these charters to operate at a lower per-pupil cost; the savings can be used to offer more competitive wages, which in turn allows for a longer school day. There is a question, however, as to whether this staffing model can be brought to a larger scale, as the supply of novice teachers in New Jersey is shrinking.[13]

Conclusion: Stemming the “Whitening” of Camden’s Teachers

There are at least two reasons why Camden should care about the changes in its teaching workforce. First, students of color benefit from having teachers of color in their schools. In Camden, this means policies should be in place to support the recruitment and retention of Black and Hispanic/Latinx teachers across all sectors: CCSD, charters, and renaissance schools.

Second, the policies that have led to fewer Black teachers in Camden’s schools have been established by the state and are not the result of local action. CCSD has operated under a state fiscal monitor since 2006 and under full state control since 2013. The plan to close CCSD schools and replace them with charter schools was developed by the Christie administration without local input.[14] The Urban Hope Act, which established renaissance schools, is a state initiative but has been confined solely to Camden.

The whitening of Camden’s teacher workforce is the result of policies imposed by outside forces. Yet these very policies have resulted in fewer jobs for Black teachers in a predominantly Black city.[15] The policymakers who have caused this shift have an immediate obligation to acknowledge the problem and propose solutions to address it.

End Notes

[1] April Saul, (1/8/21), WHYY. “‘How am I going to drop off my kids?’: Parents, stakeholders fret at proposed Camden school closures.” https://whyy.org/articles/how-am-i-going-to-drop-off-my-kids-parents-stakeholders-fret-at-proposed-school-closures-in-camden/

[2] https://www.state.nj.us/education/chartsch/renaissance/docs/2014UHA.pdf

[3] Georgie E. Norcross, III, (4/13/17), The Star-Ledger. “Working together has saved Camden’s schools | Opinion.” https://www.nj.com/opinion/2017/04/working_together_has_saved_camdens_schools_opinion.html

[4] Stephen M. Eells, Office of the State Auditor, New Jersey. (1/15/2019). City of Camden School District.https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/legislativepub/Auditor/341017.pdf

[5] Throughout this report, I refer to “teachers” as certificated staff who do not hold administrative positions. These staff include those who are not in instructional positions but provide student support, including counselors, occupational and physical therapists, nurses, librarians, speech therapists, and so on. “Teachers” in this report does not include those who do not hold a certificate, such as paraprofessionals, custodians, cleric workers, etc.

[6] John Mooney (6/6/2013). Nj Spotlight. “Camden Schools Takeover: Day One, and Counting” https://www.njspotlight.com/2013/06/13-06-05-camden-schools-takeover-day-one-and-counting/

[7] Winnie Hu (10/30/2006).The New York Times. “In New Jersey, System to Help Poorest Schools Faces Criticism.” https://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/30/education/30abbott.html

[8] John Mooney, (7/18/17). Nj Spotlight. “Christie’s Charter Legacy: A Clear Record of Growth.” https://www.njspotlight.com/2017/07/17-07-18-christie-s-charter-legacy-a-clear-record-of-growth/

[9] NJDOE data divides teacher race/ethnicity into seven categories: white, Black, Hispanic, Asian, Native American, Hawaiian Native, and two or more races. (See: https://www.nj.gov/education/data/cs/) The percentage of teachers in the last four categories totaled never rises above 4 percent in the data and is excluded from this analysis.

[10] Mark Weber (2020). New Jersey’s Shrinking Pool of Teacher Candidates. The New Jersey Policy Perspective: Trenton, NJ. https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/new-jerseys-shrinking-pool-of-teacher-candidates/

[11] Mark Weber (2019). In Brief: New Jersey’s Teacher Workforce, 2019. The New Jersey Policy Perspective: Trenton, NJ. https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/in-brief-new-jerseys-teacher-workforce-2019-diversity-lags-and-wage-gap-persists/

[12] Mark Weber (2019). Ten Important Facts About New Jersey Charter Schools… And Five Ways To Improve The New Jersey Charter Sector. New Jersey Education Policy Forum; New Brunswick, NJ. https://njedpolicy.wordpress.com/2019/04/26/ten-important-facts-about-new-jersey-charter-schools-and-five-ways-to-improve-the-new-jersey-charter-sector/

[13] Mark Weber (2020). New Jersey’s Shrinking Pool of Teacher Candidates. The New Jersey Policy Perspective: Trenton, NJ. https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/new-jerseys-shrinking-pool-of-teacher-candidates/

[14] See: Mark Weber (5/2/2012). “NJDOE Coup D’Etat.” (blog post). http://jerseyjazzman.blogspot.com/2012/05/njdoe-coup-detat.html

[15] US Census Bureau data, Camden, NJ, 2019: https://data.census.gov/cedsci/profile?q=ACSDP5Y2019.DP05%20Camden%20city,%20New%20Jersey&g=1600000US3410000 Camden’s population by race: White alone, 23.5%; Black or African American alone, 41.4%; Some other race alone, 27.6%, two or more races, 4.5%; Asian alone, 2.4%.