To read a PDF version of this report, click here.

By Brandon McKoy, Sheila Reynertson, and Raymond Castro

All New Jerseyans should have the opportunity to lead a healthy life, no matter where they live or how much money they make. State policymakers can foster this opportunity for all Garden State residents by unleashing targeted public investments and making smart budget and tax policy decisions. Lawmakers — as well as health care leaders — need to look beyond traditional investments in health care services and access (think insurance, hospitals, and the like), and consider how the state’s investments in education, housing, and other socioeconomic and environmental factors can eliminate the barriers to a healthy life for New Jerseyans.

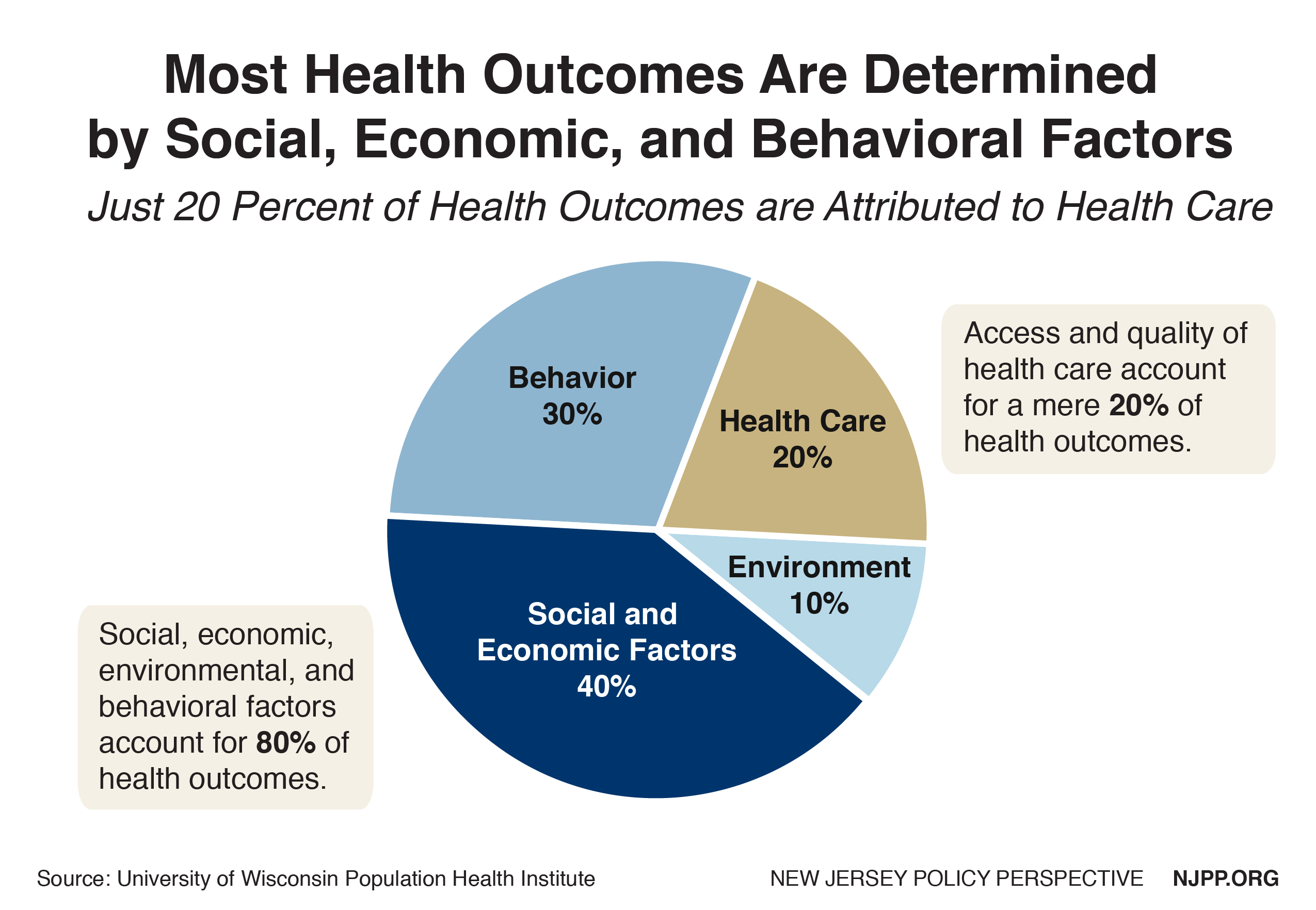

While access to health care does play an important role in influencing health outcomes, the conditions and circumstances in which people live, work, learn, and play are very influential in shaping how healthy they feel and how long they live. One widely recognized and validated model, from the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, suggests that 80 percent of health outcomes are determined by social and economic, environmental, and behavioral factors; just 20 percent are attributable to health care.[1] Social, economic, and environmental factors are largely shaped by state and federal policy and budget decisions.

Low-Income New Jerseyans Face Unique Barriers to Healthy Living

Healthy people and communities are the building blocks of a strong and thriving New Jersey. Since state policymakers expanded Medicaid in 2013, New Jersey’s uninsured rate rapidly dropped to 8 percent in 2017 from 13.2 percent in 2013. However, a number of barriers prevent many Garden State communities from experiencing good health, including economic instability and hardship; limited access to healthy, affordable food; lack of affordable housing; and exercise options in safe, walkable neighborhoods.

In short, opportunities for Americans to be healthy are not distributed equally. As documented by many studies, there is a direct relationship between income and health with low-income Americans having poorer self-reported health status across all racial and ethnic groups.[2]Meanwhile, a history of structural racism and inequality have helped create especially poor health outcomes for Americans of color, who are more likely to report their health as fair or poor than their White peers. And low-income people of color have the poorest self-reported health status of all, with more than 1 in 5 low-income Black and Latinx people reporting fair or poor health (among racial groups where data are available: Black, Latinx, and White).[3]

In New Jersey, these health inequities can be viewed geographically and demographically, though it’s worth noting that due to historically racist policies in housing and other areas, residential segregation has created a situation with many demographically homogenous geographies across the Garden State. This is not so evident at the county level, but much more so at the ZIP code level.

For example, the share of residents in poor or fair health is just 11 percent in New Jersey’s healthiest county (Morris) and 23 percent in the state’s least healthy county (Cumberland). The disparities across racial and ethnic lines are even more severe: just 11 percent of White and Asian New Jerseyans are in poor or fair health, compared to 20 percent and 32 percent of Black and Latinx New Jerseyans, respectively.[4]

Where one is born and resides in New Jersey can have a big impact on how long one lives. Take life expectancy in the Trenton area, for example. In the 08611 ZIP code, which includes the Chambersburg and Mill Hill neighborhoods, the average life expectancy is 73 years. As one moves north and east of Trenton, people live longer lives: In the 08619 ZIP code, that includes neighborhoods in both Trenton and Hamilton, the average life expectancy jumps 10 percent, to 80 years; and moving farther out to the 08550 ZIP code (the Princeton Junction section of West Windsor), the average life expectancy increases another 9 percent, to 87 years.[5]

This neighborhood-by-neighborhood disparity is not limited to Mercer County, of course. One finds similar results when comparing life expectancy in Camden and Cherry Hill, or in Newark and Montclair, for example.

Overall, New Jerseyans of color are less likely to achieve greater health than their White neighbors — no matter where they live. While close to 60 percent of White New Jerseyans have “good or excellent health,” according to the health equity metrics developed as part of the Health Opportunity and Equity (HOPE) Initiative, less than 45 percent of Black, and less than 35 percent of Latinx, New Jerseyans do.[6]Black New Jerseyans also have significantly lower average life expectancies, and higher rates of infant mortality, than their White or Latinx neighbors.[7]

Building Healthy Communities and Advancing Equity Through Public Policy

New Jersey policymakers should focus on improving the health and well-being of all the state’s residents by implementing sound policies that lift people out of poverty and boost opportunity, and by leveraging the state budget to support programs beyond investments in health care. Many programs and policies that may not seem health-related on the surface can help build healthy communities and advance equity.

The good news is that New Jersey has already taken major steps in this direction; lawmakers ought to build on that foundation of progress in 2019 and beyond. Here’s how.

Make Health Care Affordable for All New Jerseyans

Polls in New Jersey have shown that health care costs were the number one issue in the midterm elections last year. This is understandable because New Jersey is often ranked among the top states in medical costs. To help address this issue, policymakers enacted a reinsurance program and reinstated the individual mandate that was repealed at the federal level, both of which have and will continue to reduce insurance costs.[8]Nevertheless, much more needs to be done. New Jersey lawmakers should:

- Make all uninsured children eligible for NJ FamilyCare (includes Medicaid and CHIP) regardless of immigration status and income

- Establish a commission to oversee and set caps on the excessive costs of prescription drugs

- Raise Medicaid reimbursement rates for pediatric services that are not sufficiently accessible to low-income children

Boost the Income of Workers and Their Families

In a high-cost state like New Jersey, far too many workers and their families are not paid enough to make ends meet. This creates a wide range of barriers to better health for hundreds of thousands of New Jerseyans who are unable to afford a decent, safe place to live; or who struggle to regularly put nutritious meals on the table; or who must cope with the toxic stress and uncertainty that comes with being unable to secure basic economic security.

To allow all New Jerseyans the chance to live healthy, thriving lives, policymakers must boost the income of these workers and their families on both payday and at tax time.

Raise the minimum wage

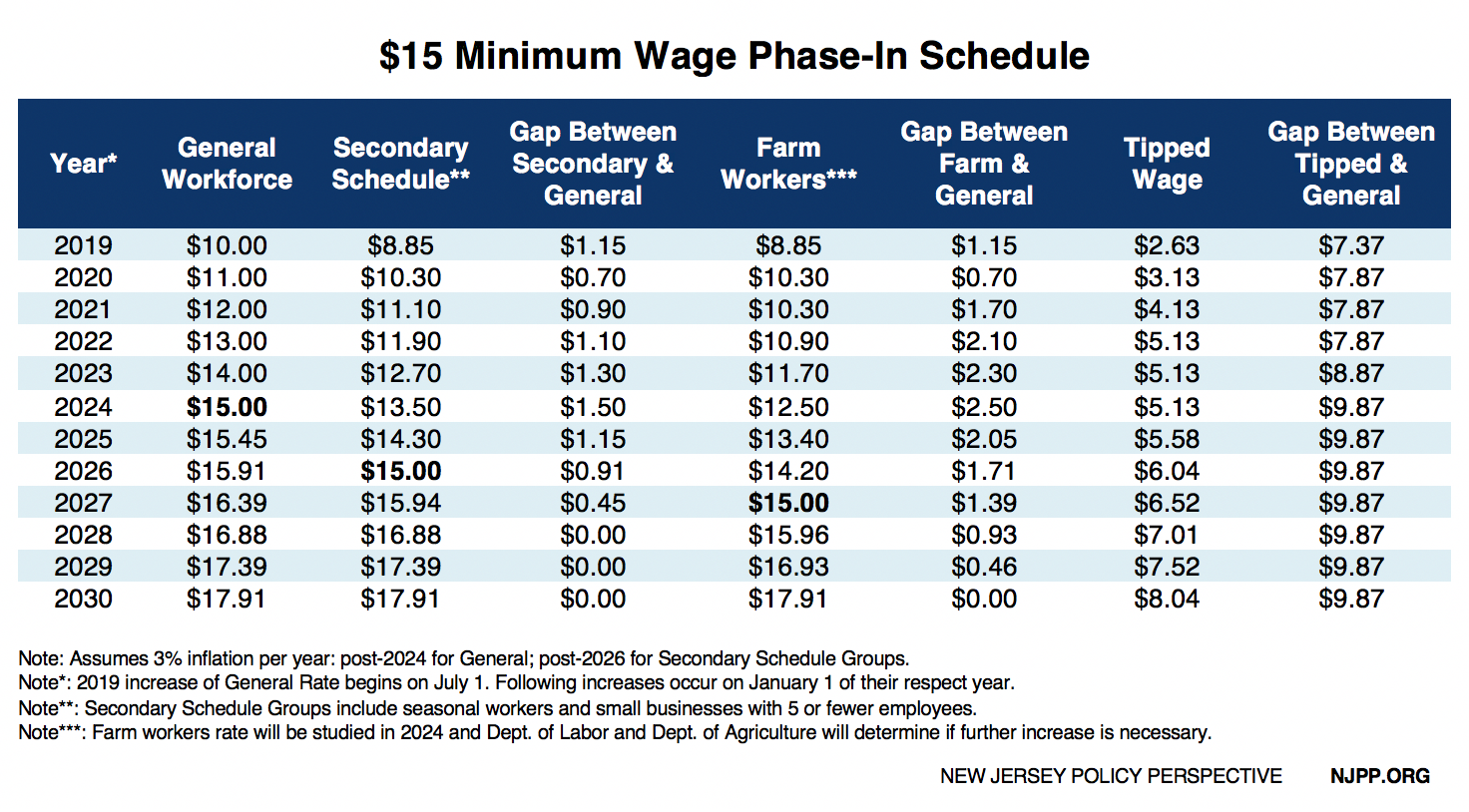

New Jersey’s minimum wage in 2019 is $8.85, a woefully inadequate rate that does not help workers meet their basic needs. But thanks to the hard work of NJPP and our allies, the Governor signed into law an increase in the wage to $15 by 2024 for most workers, after which future increases will be tied to inflation. The wage will go up to $10 on July 1, 2019, and then increase to $11 on January 1, 2020. The wage will then increase $1 on January 1st each year until reaching $15 in 2024. This increase will benefit about 1 million of the state’s workers, helping them meet their daily needs and improving our economy.[9]

Some workers are on a separate, slower phase-in schedule. Those who are employed as seasonal workers or at businesses with fewer than 6 workers will get to $15 by 2026, after which there is a provision to bring them to parity with the general wage by 2028. For farmworkers, they will get to $12.50 by 2024, after which the Commissioner of Labor and Secretary of Agriculture will determine whether they should continue to $15. If they decide in the affirmative, farm workers will reach $15 by 2027, after which they will reach parity with the general wage by 2030.

New Jersey’s tipped wage will also get a small increase to $5.13 from the federal tipped minimum wage of $2.13. While this is important, the tipped differential between the tipped wage and the minimum wage will go from $6.72 in 2019 to $9.87 in 2024, a development that we have advised against. NJPP has reported on the unique challenges faced by workers who rely on tips for a majority of their pay, from increased instances of wage theft to a heightened risk of assault and sexual harassment. NJPP and labor advocates will continue to push for the complete phase out of the tipped wage.

Nevertheless, this is a hugely important change that will reverberate throughout New Jersey’s economy. As one of the slowest states to emerge from the Great Recession, and with a population where four out of ten households essentially live paycheck to paycheck and have trouble making ends meet, raising the minimum wage to $15 will be transformative for the state’s workers, families, and businesses.[10]Lawmakers should develop new legislation to phase-out the tipped wage altogether, a move that would significantly improve the economic security and work experience of tipped workers.[11]

Expand tax credits for working families

Increasing take-home pay for low-paid workers is a critical step toward increasing economic security and the prospects for better health. It is equally critical for policymakers to ensure low-income and working-class families aren’t unduly punished by an upside-down tax code that asks them to pay greater shares of their income to state and local taxes.

The federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) provides low-paid workers with a boost to their incomes in the form of a tax refund. This credit lifts more than 5 million Americans — including 3 million children — out of poverty each year, and reduces the severity of poverty for many millions more.[12]The EITC has been shown to have tremendous widespread benefits, including improved health for infantsand mothers.

New Jersey — like 28 other states and D.C. — has a state EITC that builds on the federal credit and helps even out the tax code and increase opportunity for working families and their children.[13]Children who get additional income through programs like the EITC tend to do better and go farther in school and tend to work and earn more as adults — all of which can have a strong, positive effect on their ability to live healthier lives.

The state EITC in New Jersey is strong, thanks to a longstanding tradition of bipartisan support in the legislature and governor’s office. Last year, policymakers came together and agreed to increase the state EITC from 35 percent of the federal credit to 40 percent over three years. This will put tens of millions of more dollars each year in the pockets of over half a million New Jersey families.

Lawmakers should build on the success of this vital credit by expanding it to an important group of low-paid workers that the EITC largely ignores: adults who aren’t raising children. California, Maryland, Minnesota, and the District of Columbia have already expanded their EITCs to include these workers; hundreds of thousands of low-paid New Jersey workers could receive a much-needed boost to help make ends meet if Garden State lawmakers follow suit.[14][15]

New Jersey policymakers took another big step last year to help the state’s lower-income working families at tax time when they created a new child and dependent care tax credit (CDCTC) for 74,000 families with annual incomes of less than $60,000. It is based on the federal credit, which allows parents and caregivers to deduct up to 35 percent of employment related care expenses from their federal taxes. However, New Jersey caps the CDCTC at a low 50% of the federal credit and is nonrefundable, meaning it will offset the tax due but cannot reduce the tax below $0. Making the CDCTC fully refundable and at a more generous percentage of the federal credit would help the families that need it the most. Half of the states and D.C. currently offer these credits. In twelve states the credits are fully refundable.

Ensure All Workers Have the Ability to Balance Work and Family Needs

Expand paid family leave

In 2008, New Jersey became the second state to adopt a paid family leave policy. Nearly a decade into the Family Leave Insurance (FLI) program, it’s a clear success, having replaced hundreds of millions of dollars in lost wages for tens of thousands of New Jerseyans who needed to take time off to be with a new child or sick family member.

The existence of this program is a boon for health in New Jersey, particularly for the health of young children. A period of paid leave after the birth of a child contributes to the healthy development of infants and toddlers. There is evidence linking paid leave to better maternal and child health outcomes, like reduced infant and post-neonatal mortality rates; increased breastfeeding, well-child medical visits, and immunizations; and improved health outcomes for children in early elementary school, including reduced issues with maintaining a healthy weight, ADHD and hearing-related problems, particularly for less-advantaged children.[16]

And yet this trailblazing program is falling short of its potential, with serious repercussions for New Jersey families and for the state’s economy. The program is not widely advertised, particularly among low-paid workers. And the wage replacement level and cap on earnings are so low that many workers across the income scale simply cannot afford to take advantage of what should be an important benefit.

In January 2019, legislation to improve and expand the NJ Family Leave Insurance Program passed both houses. The reforms and additional changes in the bill will go a long way to make the program more accessible for working families, especially those struggling to balance work and family caregiving. With the bill on the Governor’s desk, New Jersey is poised to both remove the barriers that have stopped many people from taking paid family leave and increase public awareness of the program so that no one will have to choose work over the time to heal or care for a loved one in need. These improvements will be fully funded by a small increase to current worker contributions, with measurable benefits for families, employers and the state’s economy. Specifically, the new law will:

- Allow workers to take up to 12 weeks of paid leave

- Increase the current two-thirds wage replacement

- Raise the very low cap on earnings while on leave

- Expand job protections for 200,000 workers employed at companies with 30 to 50 workers

- Expand the definition of family to include grandparents and grandkids, siblings, adult children, parents-in-law, and chosen family

- Provide benefits for survivors of domestic violence or sexual assault and to those caring for survivors

- Increase public awareness with designated funding for outreach

Ensure sound implementation of earned sick leave

Until last year,over 1 million New Jerseyans, mostly in low-paid jobs, couldn’t get paid if they needed to take time off because they were sick. And for many, taking an unpaid day off meant forfeiting their job. Last year state policymakers fixed that problem.

The New Jersey Earned Sick Leave Law — which went into effect on October 29, 2018 — allows employees to accrue 1 hour of earned sick leave for every 30 hours worked, for up to 40 hours each year. This new law is important for workers, particularly low-paid workers, and also for public health.

Earned sick leave has been linked to reducing preventable hospitalizations and emergency-room visits; stopping the spread of illness (particularly foodborne illness, since the restaurant industry is one where workers are least likely to have employer-sponsored access to earned sick days); and more.[17][18]People who come to work sick also get injured more often, particularly in high-risk occupations like manufacturing, construction, healthcare and agriculture.[19]

Being able to take earned sick days is also very important for working parents. When they aren’t allowed to take earned sick days, parents face the difficult decision of caring for themselves and their loved ones or showing up for work, a choice which could extend the duration and increase the severity of an illness.

We have seen evidence right here in New Jersey of how earned sick leave policies can improve health. In Jersey City, which was the first New Jersey municipality to pass an earned sick leave policy in 2014, fewer sick Jersey City employees are coming to work, reducing the risk of illness spreading around the city — an important finding that promotes both public health and a stronger economy.[20]

The New Jersey Department of Labor is now in the process of finalizing regulations which appear to be strong interpretations consistent with Earned Sick Leave Act. They establish clear guidelines for New Jersey employers about their new obligations and employees about their rights to access earned time off to recover from an illness or help a sick loved one. To ensure New Jersey workers and employers learn about the law, regulations will also provide for general outreach and education efforts in multiple languages.

Invest in the Building Blocks of Healthy, Strong Communities

Continue expanding access to high-quality preschool

Universal high-quality preschool prepares children for school and has been found to boost their test scores, high school graduation rates and employment opportunities, as well as their long-term health.

Children who participate in high-quality early childhood programs experience immediate and long-term health-related benefits.[21]They also tend to go farther in school; setting up another wave of positive outcomes, since people with more education live longer, are less likely to die from cancer or heart disease and have better access to health care and insurance.[22]

In 2008, the legislature recognized the value of expanding access to high-quality early education, passing the School Finance and Reform Act to bring preschool to more towns across the state. Still, many New Jersey’s children lack access to early education. That’s because many successive governors and legislatures have yet to deliver on the promise of the 2008 law. That has begun to change, and in last two state budgets lawmakers dedicated over $100 million in additional funding to expand state-funded, full-day preschool for 3- and 4-year-olds to more school districts.[23]As a result, the number of districts providing at least partial access to high-quality public preschool has more than tripled, from 35 just two years ago to over 100 today.[24]

New Jersey policymakers should continue to take steps to fully fund the 2008 law and expand preschool to more districts, but they also ought to think bigger and bolder and work towards implementing truly universal preschool across the entire state, in every district.

Make public transit more accessible, affordable, and reliable

Transportation is a monumental issue for New Jersey, and here more than anywhere else the conversation about transportation must be about public transit. But, despite the fact that nearly a million New Jerseyans use public transportation on a daily basis, the political and policy culture of the state remains dominated by car-centric thinking. This is an enormous problem for the most densely populated state in the nation.

As a result, public transit in New Jersey is in crisis. The infrastructure is decaying. The funding streams are dried up, and the funding structure is broken. As a result, the costs to commuters are rising. And still, the service is getting worse. Low-income residents and New Jerseyans of color are disproportionately harmed by this public transit crisis that is also making our communities less healthy.

This must change. After all, increased use of public transit has a positive effect on health. It improves local economies, helping boost working families and their long-term health. It makes the air cleaner and safer for New Jerseyans to breathe by getting more automobiles off the roads. And it leads to more physical activity too — public transit users, on average, walk more than drivers. And the connections between bicycle infrastructure and transit infrastructure show tremendous promise, helping to extend the reach of public transit and get more riders on buses and in trains, without further clogging local roads — and doing so in a way that is more affordable for less well-off residents.

But public transit’s social, economic and health benefits don’t exist if there are no riders, or not enough riders. And if the transit system is unaffordable, unreliable and unsafe due to years of disinvestment, the riders will — if they can — stay away.

New Jersey has shirked its responsibility to invest the dollars necessary to create a reliable, affordable, modern public transit system. In 2016, policymakers took a big step toward fixing this problem by raising fuel taxes to help pay for capital investments in transit modernization and for expansion across the state. That will help, but it will not fix New Jersey’s long-standing underfunding of NJ Transitoperatingcosts.

Lawmakers must find adequate, stable and dedicated funding for NJ Transit’s operations. From 2005 to 2017, the state slashed direct support of NJ Transit by 59 percent. This meant NJ Transit increasingly turned to riders to make up the difference. Major fare hikes raised rider contributions by 45 percent over the same time.[25]

Riders pick up far more of the tab for NJ Transit (52 percent) than they do for most peer transit agencies around the country. In Chicago, for example, riders pay for 38 percent of operations and in Los Angeles, just 22 percent. This is a direct result of how little of NJ Transit’s operating budget is covered by dedicated taxes — just 1.3 percent, compared to 51 percent in Chicago and 58 percent in Los Angeles.

Dedicated, stable annual revenues are necessary to support NJ Transit’s operating budget. Lawmakers should consider a variety of options, including congestion pricing, a surcharge on gas-guzzling automobile purchases and taxing businesses that disproportionately benefit from transit (as New York’s Metropolitan Transit Agency does). Ensuring stable and adequate support for operating expenses will prevent NJ Transit from imposing even more fare hikes or capital funding raids.

Reverse disinvestment in higher education

People who attend and graduate from college have a greater shot at economic success — and at living healthier lives. Now more than ever, Americans with less education are dying earlier than their peers; more likely to have major diseases, such as heart disease and diabetes; more likely to have risk factors that predict disease, such as smoking and obesity; and more likely to have diminished physical abilities for health reasons or to be disabled.[26]

New Jersey policymakers concerned with improving health outcomes for all residents shouldn’t overlook the role of affordable public higher education — and should work to reverse the recent trend of sustained disinvestment in New Jersey’s public colleges and universities.

At a time when more students than ever are seeking to secure their families’ future with a college education, New Jersey has slashed funding for its institutions of higher learning and shifted the cost burden onto the shoulders of striving students and their families. Between 2008 and 2018, New Jersey’s funding for public four-year colleges and universities dropped 24 percent, representing a $2,387 cut per-student. Over that same period, average tuition costs at public four-year colleges and universities increased 18 percent, or $2,075, from $11,973 in 2008 to $13,868 in 2018.

This results in an increasingly heavy burden for New Jersey families. In 2017, average tuition and fees at a public four-year institution accounted for 17 percent of a New Jersey family’s median income. For families of color — who often face additional barriers to employment and increased difficulty accessing jobs that pay better — the situation was far more severe, with those costs accounting for 27 percent of a Black New Jersey family’s median income and 25 percent of a Latinx family’s median income.[27]

To slow the increase in unaffordable college prices and rising student debt, New Jersey should at the very least return to pre-recession levels of funding for higher education.

Raise adequate revenues in an equitable way

Creating opportunities for all New Jerseyans to lead healthier lives requires investments beyond traditional health care spending. It is essential to apply a health lens to the way the state raises and spends money, because health starts with where we live, learn, work, and play. Great schools, safe and vibrant communities, quality jobs, and programs that lift and keep people out of poverty strengthen our economy while creating opportunities for healthier New Jerseyans in every corner of the state. To support these foundations of thriving communities, our state needs dependable revenues that are equitable, sustainable, and adequate.

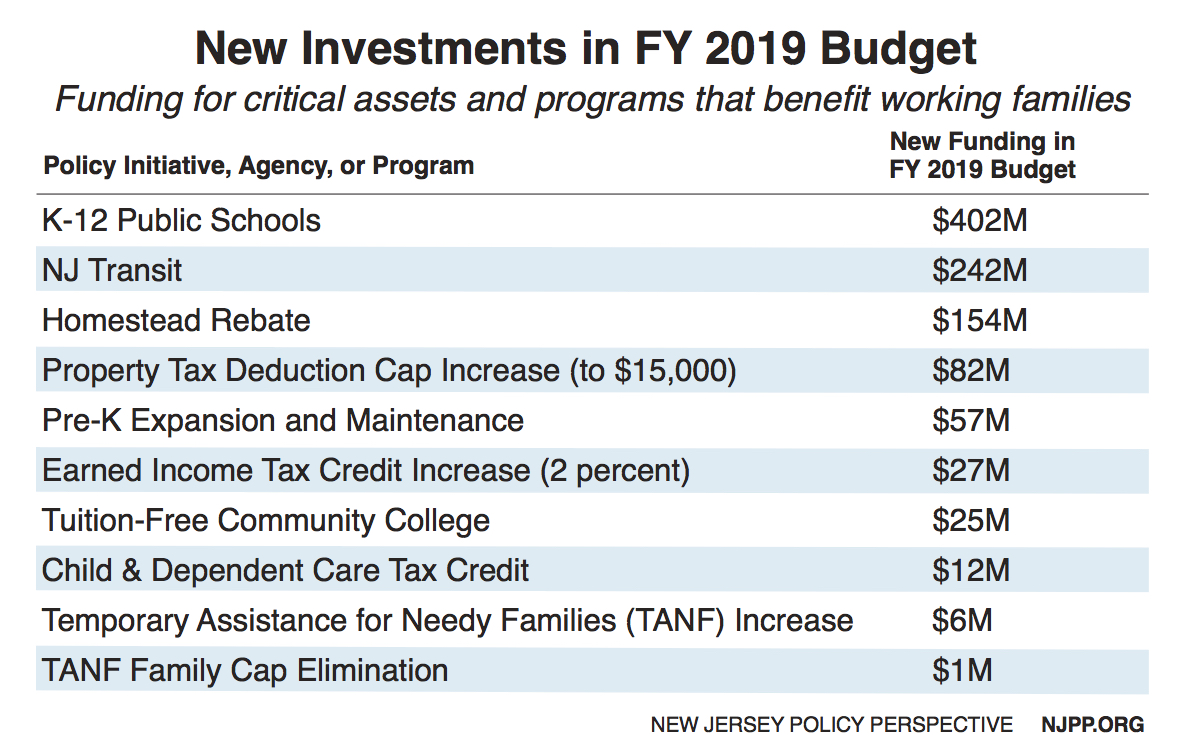

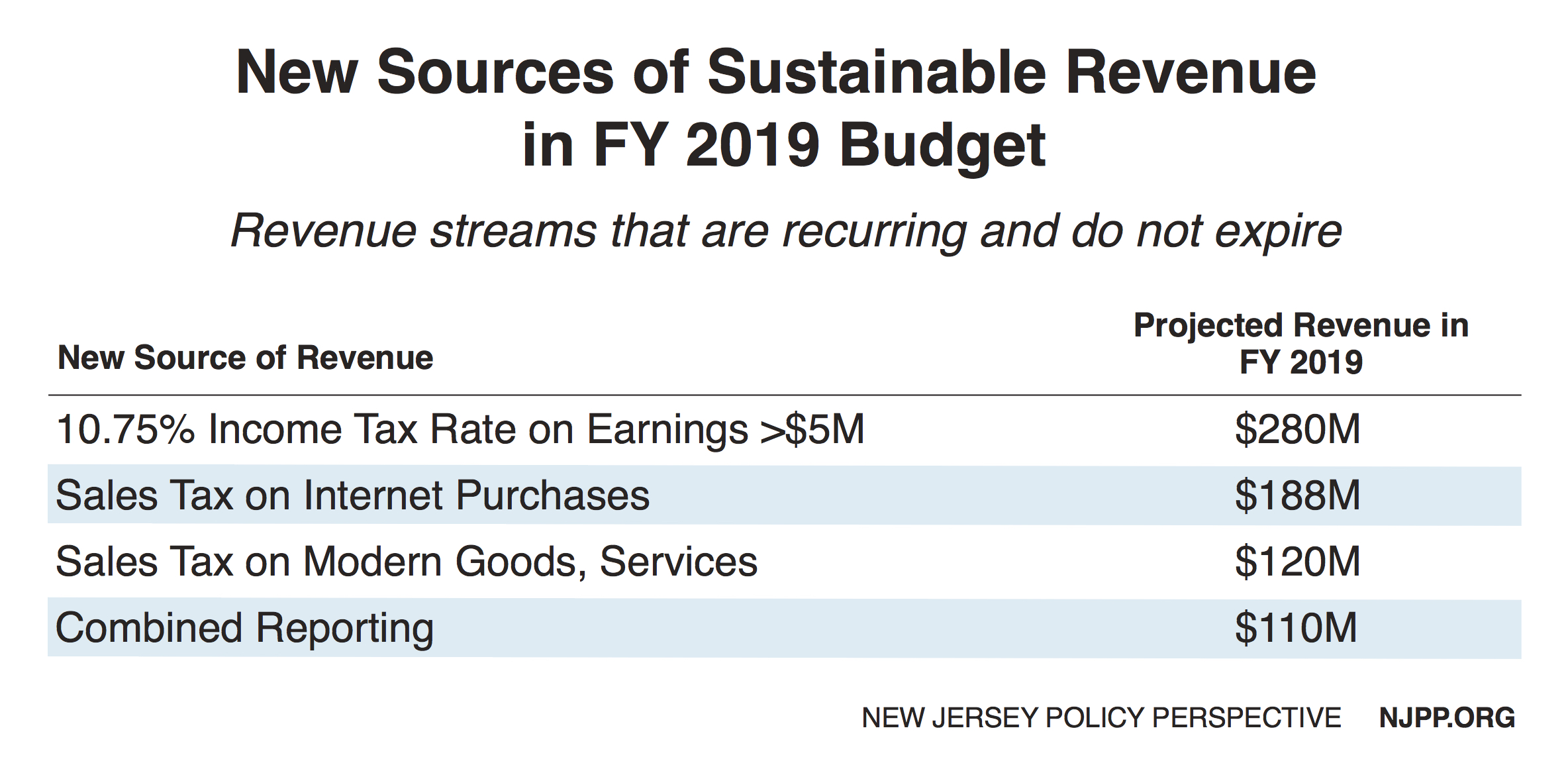

The good news is that New Jersey’s fiscal year 2019 budget, the first of Governor Murphy’s administration, signaled a much-needed reversal after nearly a decade of austere fiscal policy.[28]After years of neglect, assets critical to New Jersey’s economic success, like K-12 schools, public transit, and county colleges all received modest increases in state funding. However, the most recent budget falls short in one key area that has plagued the state and its finances for three decades: there are simply not enough stable, long-term sources of new revenue to sustain these increased investments.

Policymakers should build on the steps taken in the FY 2019 budget by implementing adequate revenue streams. Doing so will help unleash important public investments that can boost opportunity and the long-term health of New Jersey’s current and future generations.

Policymakers should:

- Continue to make the state income tax more based on the ability to pay, by levying higher marginal rates on income over $1 million

- Restore adequate taxation of inherited wealth

- Reform and minimize corporate tax breaks for economic development

- Modernize the sales tax and return the base rate to 7 percent

- Strengthen the state’s newly implemented combined reporting law

- Make the corporate tax surcharge permanent

Author’s Note: Support for this report was provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation.

Endnotes

[1]Patrick L Remington, Bridget B Catlin and Keith P Gennuso, “The County Health Rankings: rationale and methods,” Population Health Metrics, April 17, 2015, https://pophealthmetrics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12963-015-0044-2. Note that the County Health Rankings model does not account for genetics and biology, which are not measurable or modifiable.

[2]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2837459/

[3]Ibid.

[4]http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/app/new-jersey/2018/overview

[5]https://societyhealth.vcu.edu/work/the-projects/mapstrenton.html

[6]http://www.nationalcollaborative.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/hope_chartbook_final-1.pdf

[7]Although life expectancy for Latinx people is higher than for whites and higher than the U.S. average, the data include individuals born in the United States as well as individuals born outside the United States. Individuals born in the United States tend to have lower life expectancy than those born outside the United States. A growing body of research explores other potential reasons for longer life expectancy among Latinx populations relative to what would be expected based on their income and education levels. See: Neil K. Mehta et al., “Life Expectancy Among U.S.-born and Foreign-born Older Adults in the United States: Estimates From Linked Social Security and Medicare Data,” Demography: August 2016, 53(4): 1109-1134, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5026916/; Paola Scommenga, “Exploring the Paradox of U.S. Hispanics’ Longer Life Expectancy,” Population Reference Bureau, July 12, 2013, https://www.prb.org/us-hispanics-life-expectancy/

[8]https://www.njpp.org/healthcare/new-jerseys-individual-market-premiums-to-be-among-the-lowest-in-the-nation

[9]https://www.njpp.org/reports/increasing-the-minimum-wage-to-15-would-boost-the-economy-and-help-over-1-million-workers-but-not-if-the-legislature-stalls

[10]United Way of Northern New Jersey, ALICE Report 2019: https://www.dropbox.com/s/h3huycfbak512t2/18_UW_ALICE_Report_NJ_Update_10.19.18_Lowres.pdf?dl=0

[11]http://rocunited.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/OneFairWage_W.pdf

[12]https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/policy-basics-the-earned-income-tax-credit

[13]https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/policy-basics-state-earned-income-tax-credits

[14]https://www.cbpp.org/blog/state-eitc-expansions-will-help-millions-of-workers-and-their-families

[15]https://www.njpp.org/budget/eitc-expansion-would-provide-a-crucial-boost-to-hundreds-of-thousands-of-new-jerseyans

[16]http://www.nationalpartnership.org/our-work/resources/workplace/paid-leave/the-child-development-case-for-a-national-paid-family-and-medical-leave-insurance-program.pdf

[17]https://smlr.rutgers.edu/sites/default/files/images/NJ_HIA_-_Full_ReportApril2011_0.pdf

[18]http://www.nationalpartnership.org/our-work/resources/workplace/paid-sick-days/paid-sick-days-lead-to-cost-savings-savings-for-all.pdf

[19]https://blogs.cdc.gov/niosh-science-blog/2012/07/30/sick-leave/

[20]https://smlr.rutgers.edu/sites/default/files/documents/Jersey_City_ESD_Issue_Brief.pdf

[21]https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/the-foundations-of-lifelong-health-are-built-in-early-childhood/

[22]https://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_briefs/2014/rwjf414926

[23]https://prekourway.org/assets/Pre-K-Our-Way_ExpandNJsPreK_OCTOBER_2018.pdf

[24]https://prekourway.org/assets/Pre-K-Our-Way_WINTER-2018_Newsletter.pdf

[25]http://blog.tstc.org/2016/12/13/nj-transit-lacks-dedicated-funding-thats-not-normal/

[26]https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2014/01/education–it-matters-more-to-health-than-ever-before.html

[27]https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/unkept-promises-state-cuts-to-higher-education-threaten-access-and

[28]https://www.njpp.org/budget/opportunity-lost-consequences-and-shortcomings-of-the-fiscal-year-2019-budget