To read a PDF version of this report, click here.

The current pandemic has created unprecedented challenges to New Jersey’s finances, as hundreds of millions of dollars are being poured into stopping the spread of the coronavirus, saving lives, and protecting workers and communities across the state.[1] Once the immediate public health risk subsides, New Jersey will face a stark reality: the enormous costs associated with the response and the drain on incoming revenue needed to keep public services available and support struggling families and businesses. Even with federal aid and borrowing to help shore up expected revenue shortfalls, New Jersey will need to do more to address budget shortfalls in the short and stabilize the state’s finances in the long-term.

At the start of the Great Recession, New Jersey implemented a temporary income tax surcharge on earnings over $400,000 to plug budget holes and reinvest in the economy. But as the recession dragged on, the state let this policy expire and, instead, pivoted to a cuts-only approach to balancing the budget. This shift in policy slowed New Jersey’s recovery, illustrating the findings of research by economists at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, which found that during a recession, spending cuts are actually more harmful to a state’s economy than tax increases.[2] Facing today’s crisis, which has exposed deep-seated inequities in New Jersey’s economy, state lawmakers must avoid the mistakes of the past by avoiding damaging cuts by reforming the state’s outdated, inadequate, and unfair tax code.

A more balanced response must be taken now — one that includes increasing tax contributions from the richest five percent of earners who have repeatedly benefited from a lopsided tax system. Taken as a whole, New Jersey’s tax code has allowed the very wealthy to avoid paying their fair share towards public assets and resources.[3] These same households have also received billions of tax breaks through temporary and permanent provisions in the federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017, including a reduction in the federal estate tax that only very wealthy families pay, a cut in the personal income tax rate, and a permanent cut to the corporate tax rate.

A sensible way to address revenue shortfalls and an unfair tax code is to raise income taxes on the state’s wealthiest households. By reforming New Jersey’s income tax, our recovery can be strengthened by reducing the tax burden that low-paid and middle class families pay, while generating more revenue for public programs and services that benefit all residents. Overall, increasing and adding additional tax rates on the wealthiest households would raise approximately $1.5 billion in new revenue each year while making the overall tax code fairer.[4]

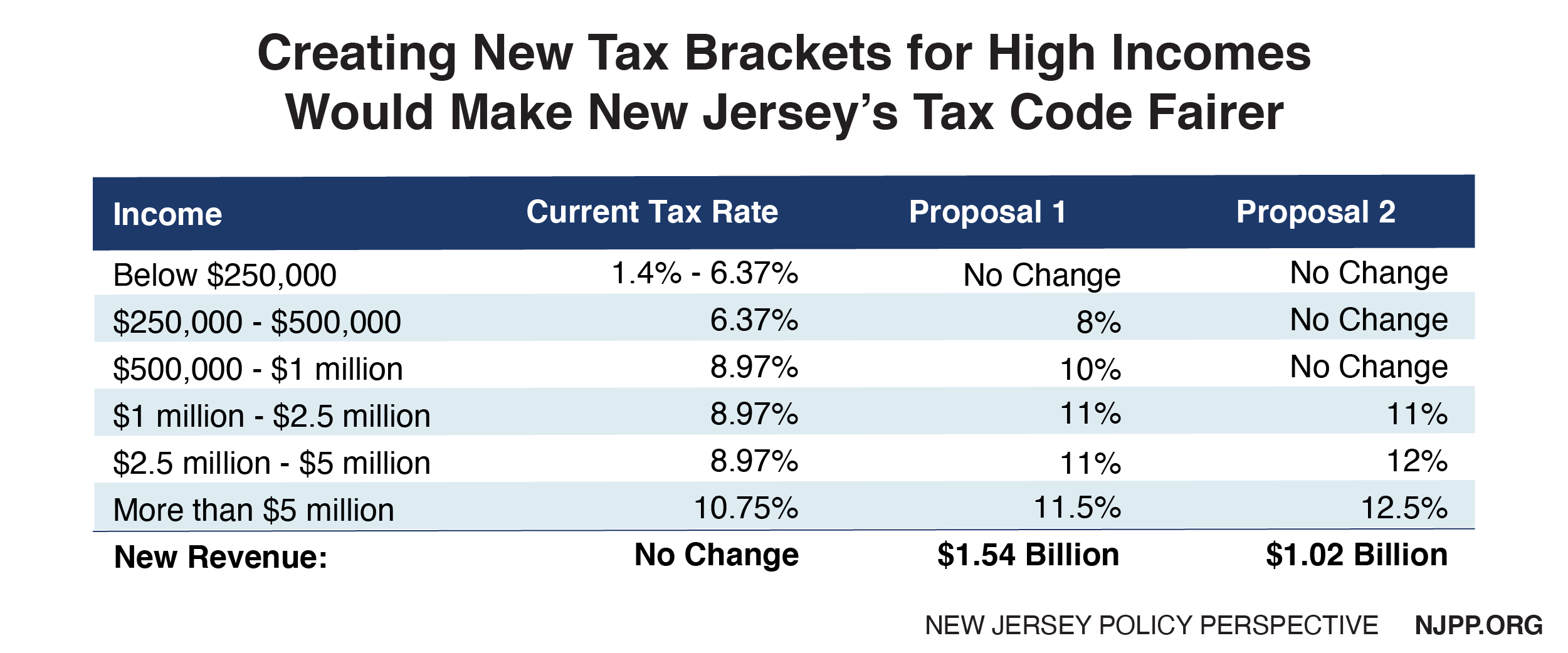

A more progressive tax code can be accomplished through targeted changes on the very top tax brackets.[5] Below are two options for improvement: Proposal 1 would create new brackets at $250,000 and $1 million, and would increase the tax rate slightly at the existing $500,000 and $5 million brackets. This would ensure that the tax increase would be paid mostly by New Jersey’s ultra-wealthy, with the top 1 percent of households — with average annual incomes of $2.46 million — paying 70 percent of the total tax increase.[6]

Alternatively, the tax changes could focus solely on those who earn more than $1 million per year who live and work in New Jersey. Proposal 2 creates two new brackets at $1 million and $2.5 million, paired with a slight increase on the existing tax rate at $5 million. However, this would raise approximately $520 million less revenue than Proposal 1.

Given these findings, Proposal 1 is unequivocally the more equitable and progressive option, and should receive support from lawmakers and advocates who seek to move New Jersey’s tax code towards a more reliable and sustainable design. While Proposal 2 requires those who earn $1 million and above to contribute their fair share, choosing to exclusively focus on millionaires is a narrow and reductive view of income inequality in the Garden State. Adjusting the income tax code to modestly raise rates on those earning $250,000 and more is both a common-sense step and one which more fully addresses the disproportionate share of wealth that is held by these households. Critically, Proposal 1 also raises approximately $520 million more than Proposal 2, which would provide greater flexibility to invest in critical assets and services that can further address racial inequities rife throughout the state.

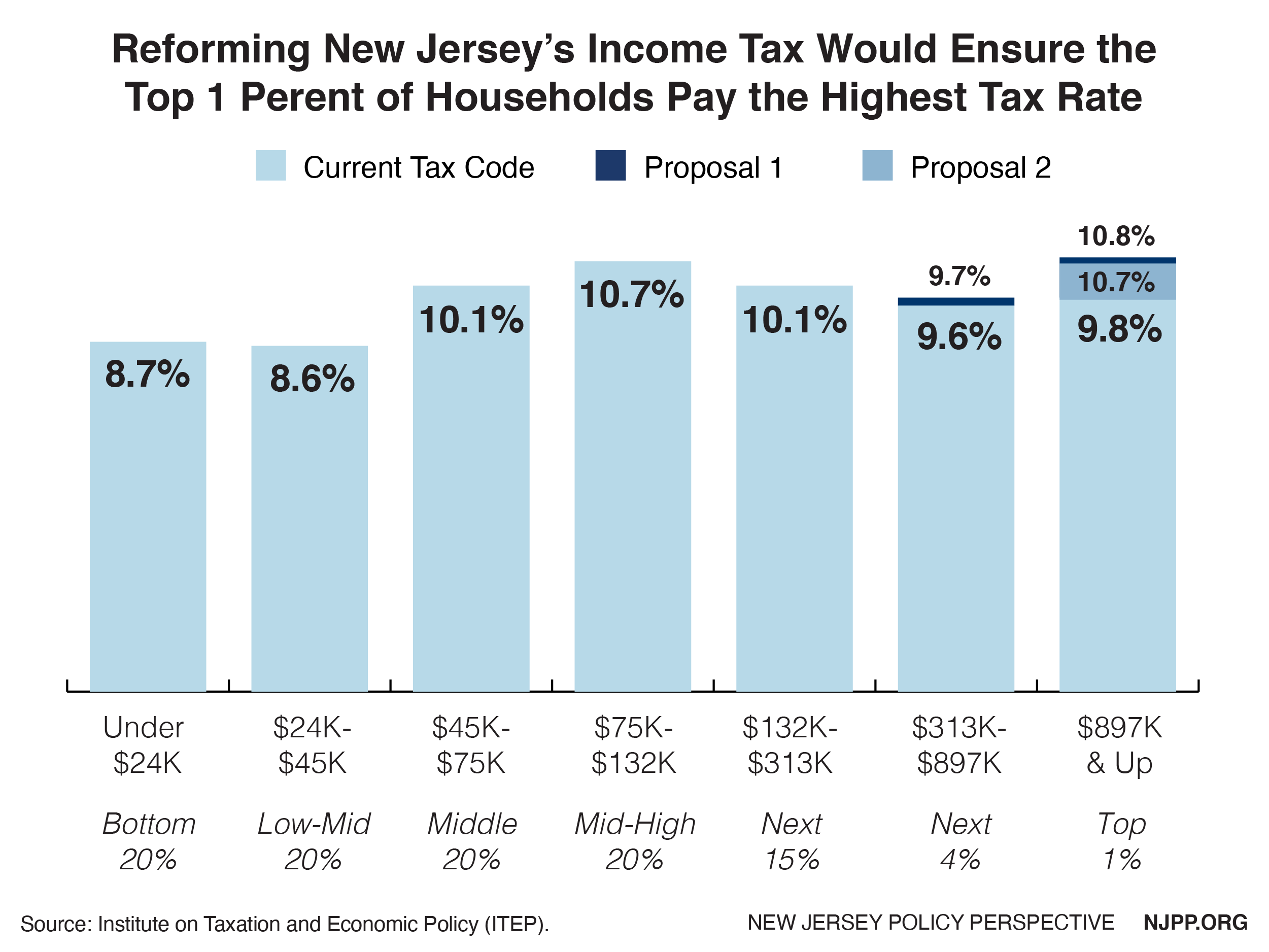

Today, middle-class New Jerseyans pay a greater share of their incomes to state and local taxes than the state’s highest earners.[7] With these proposed changes, the state income tax code would become fairer, ensuring budgets are no longer balanced on the backs of middle-class families. If Proposal 1 were adopted, the share paid by the top 1 percent would rise from 9.8 percent to 10.8 percent, a slightly higher contribution than what is paid by middle-class New Jersey families who make between $74,800 and $132,000. Proposal 2 also makes the income tax code less regressive, with the state’s top earners paying 10.7 percent of their annual income on state and local taxes, the same rate that is paid by those in the middle.

Overview and History of New Jersey’s Income Tax

New Jersey’s income tax was established in 1976 to provide better resources for schools, cities and towns, and direct property tax relief for homeowners.[8] It currently raises aproximately $16 billion in annual revenue, representing 42 percent of total state tax collections.[9] All revenue from the income tax is constitutionally dedicated to fund property tax relief, which includes school aid, teacher pensions, municipal and county aid, and direct relief for qualified veterans, people with disabilities, and senior homeowners. Despite this guaranteed revenue stream, these programs have been plagued by chronic underfunding, cuts, and delayed payments for decades. At the same time, the wealthy were given billion-dollar tax cuts and benefited from tax loopholes, lowering their overall tax responsibilities. These changes combined have created a tax code that is skewed toward the wealthy, which translates to painful cuts to public programs and services that New Jersey families, schools, and communities rely on.

Today, for single tax filers, New Jersey’s income tax ranges from 1.4 percent on incomes up to $20,000 to 10.75 percent on incomes over $5,000,000. For couples filing jointly, the tax is slightly more graduated, with lower rates in the mid-range brackets.[10]

New Jersey employs marginal tax rates, which apply different tax rates to different levels of income. As income rises, it is taxed at incrementally higher rates as opposed to a flat rate, which taxes at the same rate across all income levels. In other words, a New Jerseyan with $5,005,000 in earnings pays the top rate of 10.75 percent on only $5,000 of her earnings, not on the entire $5,005,000.

Currently, there are more tax brackets — four — under $75,000 than there are over it: three. The way New Jersey’s income tax code is designed means that $80,000 in annual earnings has the same income tax rate as $450,000. Similarly, $600,000 in earnings has the same rate as $4.9 million. New Jersey’s income tax code would benefit from a more stratified approach to higher levels of income by adding more brackets between $250,000 and $5 million.

New Jersey’s Income Tax Code: Outdated, Inadequate, and Unfair

New Jersey’s current income tax structure doesn’t accurately reflect the staggering level of income inequality that has taken root over the past 40 years. The share of all income held by the top 1 percent has steadily climbed since the Reagan administration and now approaches historical highs.[11] According to the latest data from the U.S. Census Bureau, New Jersey is the ninth most unequal state when it comes to income inequality, up from twelfth place in 2016.[12] The wealthiest households earn, on average, 37.9 times more than the middle 20 percent, according to 2019 data.[13]

While New Jersey has taken steps toward making the income tax code fairer in the past, it has failed to accurately reflect growing disparities in income:

- In 2004, a new top rate of 8.97 percent on income over $500,000 was added.

- In 2009, a temporary surcharge lowered the threshold for the 8.97 percent rate on income above $400,000 and added new tax rates of 10.25 percent above $500,000 and 10.75 percent above $1 million. This surcharge and new tax bracket expired in 2010.

- In 2019, a new top rate of 10.75 percent on income over $5,000,000 was added.

The temporary changes to income tax brackets over the $400,000 threshold raised approximately $560 million at a time when New Jersey was experiencing an enormous budget shortfall due to the Great Recession. However, the legislature allowed them to sunset a year later in 2010.[14] Subsequent efforts to reinstate these new brackets, or to otherwise make the tax code more progressive, were repeatedly vetoed by then-Governor Christie. This inaction has allowed high-earning New Jersey families to enjoy over $7 billion in cumulative tax breaks between fiscal years 2010 and 2018.[15] A permanent “mega-millionaire” tax bracket on earnings over $5 million at 10.75 percent was finally added in 2019, raising an average of $363 million a year, but this left about $400 million a year in the pockets of 18,200 New Jersey resident taxpayers and 12,800 non-residents who work in the Garden State who earn between $1 million and $5 million in annual income.[16]

Advancing Racial Equity Through Income Tax Reform

Improving New Jersey’s tax code would also address worsening racial disparities laid bare by the COVID-19 pandemic. A long history of discrimination in housing, education, employment, and the criminal justice system are all rooted in the legacy of slavery. These policies were created, and continue, to perpetuate economic advantages for white families in the Garden State. The result is a landscape of undisturbed structural racism, occupational segregation, exclusionary residential laws and practices, and massive income and wealth disparities between white households and Black and Latinx households. The typical white family in the United States has 10 times the wealth of the typical Black family and seven times the wealth of the typical Latinx family.[17] In New Jersey, the typical white family has over 52 times the wealth of the typical Black family and over 44 times the wealth of the typical Latinx family.[18] This stark and long-lasting gap means some families can respond to unexpected emergencies like a pandemic without significant hardship while others are left vulnerable and at greater risk of housing insecurity and job loss.

One of the most powerful tools driving income and wealth inequality is the tax code. Just as tax policy choices are both a symptom of, and contributor to, broader injustices, they can also be utilized to repair the damage done and advance racial equity.

For example, the 2017 federal tax law, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), actually worsened racial inequities by showering the wealthy with tax benefits at the expense of the economic security among middle-class and low-income families, which in New Jersey are over-represented by Black and Latinx households. Three-quarters of Black households (75 percent) and of Latinx households (77 percent) earn less than $81,000 a year in the Garden State.[19]

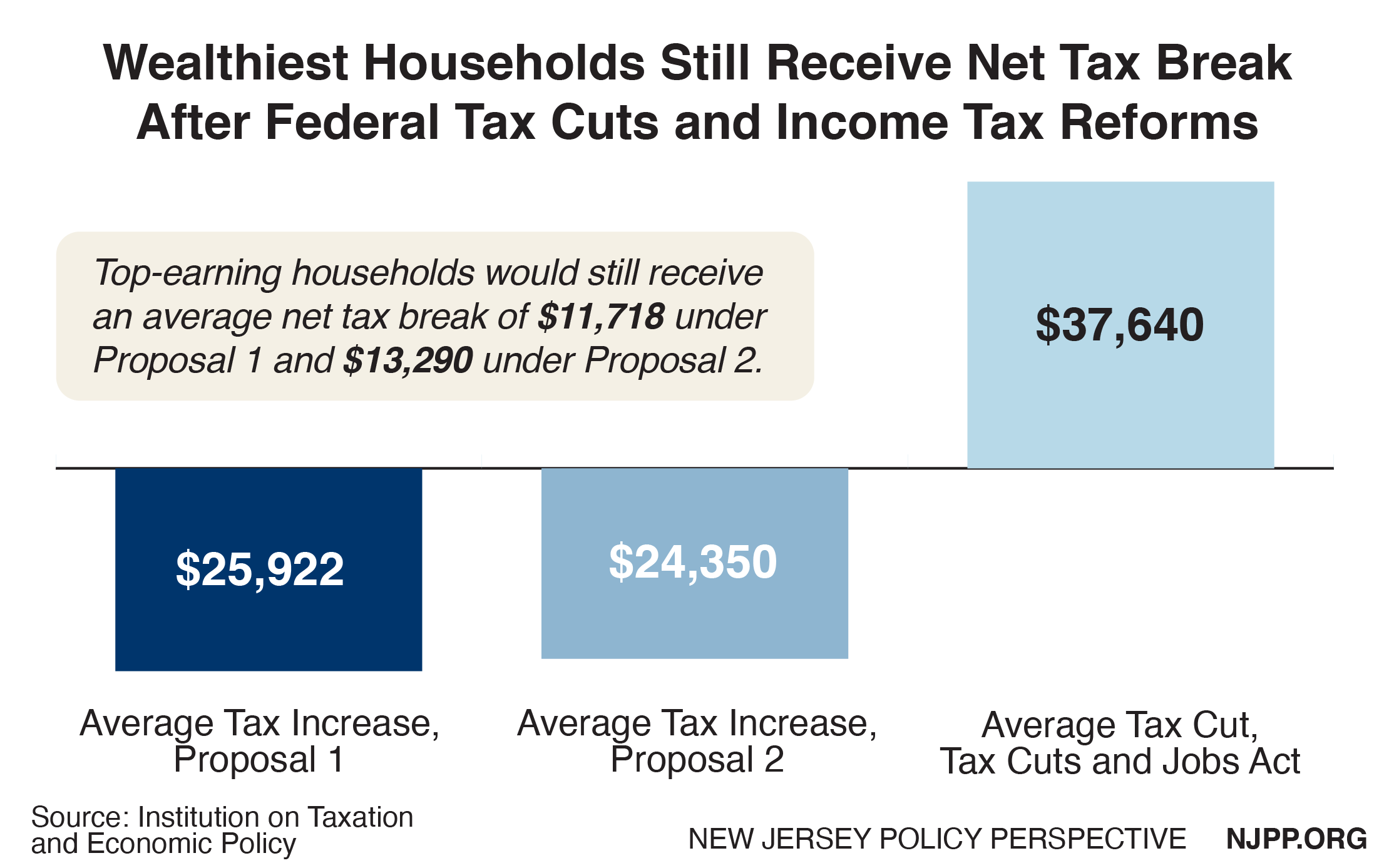

In New Jersey, the TCJA is more widely known for one provision: the temporary $10,000 cap on state and local tax (SALT) deductions, which limits how much taxpayers can deduct these taxes from their federal tax bill. But other provisions in the 2017 tax law — corporate tax cuts, pass-through tax cuts, and estate tax cuts — benefited the vast majority of the wealthiest taxpayers. That windfall means that even with the SALT deduction limitation factored in, New Jersey’s top 1 percent of earners, who are overwhelmingly white, will pocket an average of $37,640 this year.[20]

Targeted changes to New Jersey’s income tax code as proposed above could rectify this lopsided benefit, reversing course on the racial implications of the TCJA and providing the state with desperately needed resources — with the top 1 percent of earners still receiving an average net tax cut of about $12,500 when considering both the TCJA and the proposed income tax reforms.

Should the federal government repeal the SALT deduction limitation, as currently proposed by Congress in the HEROES Act, there is no reason for New Jersey to pull back on these targeted changes to the income tax code. That’s because over half (54 percent) of the benefit from a reversal of the SALT cap would go to the wealthiest 1 percent with nearly every one of those families getting a hefty tax break.[21] In fact, such a policy change all but solidifies why New Jersey must take action.

According to State Treasurer Elizabeth Maher Muoio, New Jersey is likely facing “an unprecedented fiscal crisis” with potential shortfalls that rival the Great Recession.[22] Tough decisions lay ahead with options that may or may not be available to the Garden State, including borrowing, flexible federal aid, and revenue reserves. Raising sufficient revenue for the recovery is not just a short-term goal. It is a strategic tool to protect vital investments, overcome racial inequities, and build a state economy whose benefits are widely shared.

The COVID-19 crisis has devastated communities across New Jersey. If we really are all in this together, we must guarantee that sacrifices will be shared among all residents. For decades, low-income and middle-class families — especially families of color and marginalized communities — have borne the brunt of economic recovery while enjoying none of the rewards. These proposed changes to the income tax code are the right policies at the right time and will help ensure that all New Jerseyans are paying more of their fair share to support the investments we all need to thrive.

End Notes

[1] New Jersey Department of Treasury, Report on the Financial Condition of the State Budget for Fiscal Years 2020 and 2021, May 2020. https://www.state.nj.us/treasury/omb/publications/NJ-Financial-Condition.pdf

[2] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Budget Cuts or Tax Increases at the State Level: Which is Preferable When the Economy is Weak?, April 2010. https://www.cbpp.org/research/budget-cuts-or-tax-increases-at-the-state-level?fa=view&id=1032

[3] New Jersey Policy Perspective, It’s Time to Face the Music, Jersey: We’ve Been Robbed, March 2019. https://www.njpp.org/budget/its-time-to-face-the-music-jersey-weve-been-robbed

[4] These proposals use the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) Microsimulation Tax Model, 2019. Revenue estimates will be affected by COVID-19 crisis. However, because these tax changes are targeted on high-income earnings, the estimates will likely be comparable.

[5] A tax bracket refers to a range of incomes subject to a certain income tax rate.

[6] Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) Microsimulation Tax Model, 2019.

[7] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States, 6th Edition, October 2018. https://itep.org/whopays/new-jersey/

[8] (P.L.1976, c.47)

[9] State of New Jersey, The Governor’s FY 2021 Detailed Budget, March 2020. https://www.nj.gov/treasury/omb/publications/21budget/pdf/FY21GBM.pdf

[10] New Jersey Department of Treasury, Division of Taxation, NJ Income Tax – Tax Rates, Last updated February 2020. https://www.state.nj.us/treasury/taxation/taxtables.shtml

[11] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, A Guide to Statistics on Historical Trends in Income Inequality, January 2020. https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/a-guide-to-statistics-on-historical-trends-in-income-inequality

[12] The Star Ledger, The gap between the rich and poor in New Jersey keeps increasing, data shows, March 2020. https://www.nj.com/data/2020/03/the-gap-between-the-rich-and-poor-in-new-jersey-keeps-increasing-data-shows.html

[13] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) Microsimulation Tax Model. Based on all New Jersey residents, using 2019 incomes.

[14] New Jersey Department of Treasury, Division of Taxation, Important Changes for 2010, Last updated March 2020. https://www.state.nj.us/treasury/taxation/new2010.shtml

[15] New Jersey Policy Perspective, It’s Time to Face the Music, Jersey: We’ve Been Robbed, March 2019. https://www.njpp.org/budget/its-time-to-face-the-music-jersey-weve-been-robbed

[16] New Jersey Treasury, Office of Management and Budget, Citizens’ Guide to the State Budget Fiscal Year 2019, December 2018. https://www.nj.gov/treasury/omb/publications/19citizensguide/citguide.pdf

[17] Center for American Progress, The Coronavirus Pandemic and the Racial Wealth Gap, March 2020. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/race/news/2020/03/19/481962/coronavirus-pandemic-racial-wealth-gap/

[18] New Jersey Institute for Social Justice, Reclaiming the American Dream: Expanding Financial Security and Reducing the Racial Wealth Gap Through Matched Savings Accounts, April 2019. https://www.njisj.org/new_jersey_institute_for_social_justice_releases_reclaiming_the_american_dream_expanding_financial_security_and_reducing_the_racial_wealth_gap_through_matched_savings_accounts

[19] Data shared with NJPP by Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, May 2019.

[20] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, TCJA by the Numbers: 2020, August 2019. https://itep.org/tcja-2020/

[21] New Jersey Policy Perspective, A Grain of ‘SALT’: New Jersey Needs More Than Workarounds to Respond to GOP Tax Plan, January 2018. https://www.njpp.org/budget/a-grain-of-salt-new-jersey-needs-more-than-workarounds-to-respond-to-gop-tax-plan

[22] New Jersey Department of the Treasury, Treasury Issues Preliminary Update on Projected Revenue Shortfall through Fiscal Year 2021, May 2020. https://www.nj.gov/treasury/news/2020/05132020b.shtml