To read a PDF version of the full report, click here.

When the Economic Opportunity Act was signed into law in 2013, New Jersey signaled to corporations that it was “open for business.” The idea was, by offering overly generous corporate tax subsidies, more companies would choose to expand in or relocate to the Garden State. This, in turn, would create more jobs for New Jersey residents, providing a much-needed boost to the economy.

Instead, by removing oversight safeguards and caps on awards, the economic development legislation enabled an unprecedented spike in corporate tax breaks with questionable benefits, depressing future tax revenue for years to come. Today, New Jersey is a national outlier in both the size of its corporate subsidy awards and how little the state receives as a return on its investments.

For years, New Jersey lawmakers fixated on big-ticket corporate tax incentives as a key driver of economic development without credible evidence that more is better — and little attention to the collateral consequences or opportunity costs.

But times have changed. High-profile debacles like FoxConn in Wisconsin and Amazon’s infamous HQ2 search have undermined the public’s perception of this costly strategy, both across the nation and here in the Garden State. Now is the opportune time for reform.

The next iteration of New Jersey’s economic development strategy must embrace two strategies. First, pivot away from overly generous tax breaks — with little oversight — to large corporations, and instead tailor the programs toward new companies within promising sectors in locations that have a greater need for job opportunities. Second, and more importantly, redirect the bulk of economic development dollars back into the public assets that benefit all employers and have a proven track record of making New Jersey an attractive place to grow a business: customized job training, safe roads and bridges, affordable homes, child care, and high-quality public schools from pre-Kindergarten through college.

To rein in New Jersey’s corporate subsidies, lawmakers should implement the following reforms:

- Goals driven by national best practices

- Hard caps on annual and per-job awards

- Shorter award timeframes

- Local hiring agreements

- Strict reporting and evaluation criteria

- Stronger net benefits test

- Restrict sale of tax credits

- Mandatory labor protections

- Community benefit agreements

- Prohibit awards to documented “bad actors”

By reining in New Jersey’s corporate subsidies and implementing best practices from across the nation, lawmakers can spend less and get more. They can grow an economy that truly generates prosperity for workers, their families, and their communities.

New Jersey’s Corporate Subsidies: Big Cost, Small Return on Investment

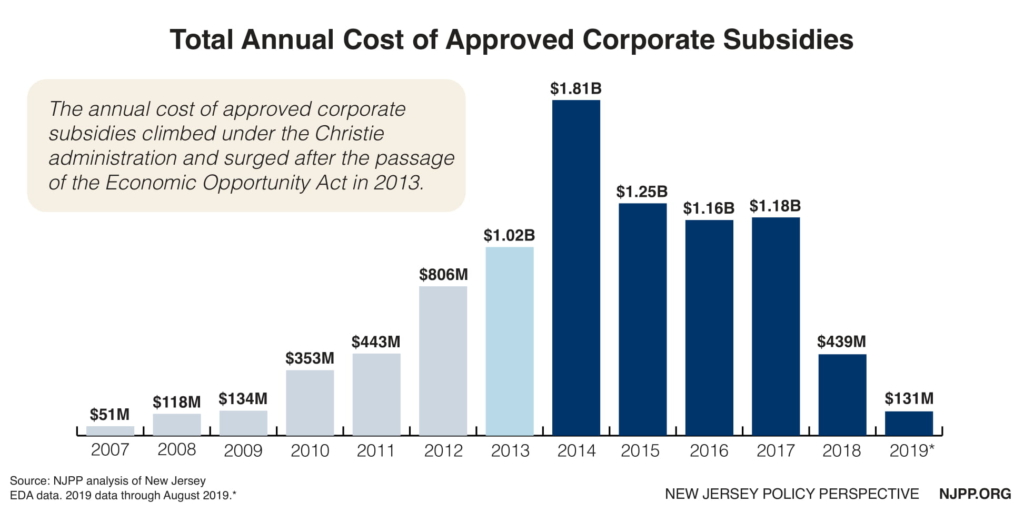

On the heels of the Great Recession and under a new administration, New Jersey lawmakers put all their eggs in one basket — corporate tax subsidies — to help jump-start the state economy. In 2010, Governor Chris Christie’s first year in office, New Jersey approved $353 million in corporate tax subsidies, a whopping 163 percent increase from the year prior. The price tag of corporate tax breaks surpassed $1 billion for the first time in state history in 2013. At the end of that year, the Economic Opportunity Act of 2013 (EOA) removed all meaningful caps and safeguards from the state’s corporate subsidy programs, opening the door for enormous tax breaks for the next several years. Meanwhile, as the state committed billions in lost tax revenue to already profitable corporations, the state simultaneously cut funding for public schools, NJ Transit, property tax relief, colleges and universities, and affordable housing — all proven drivers of widespread economic growth.

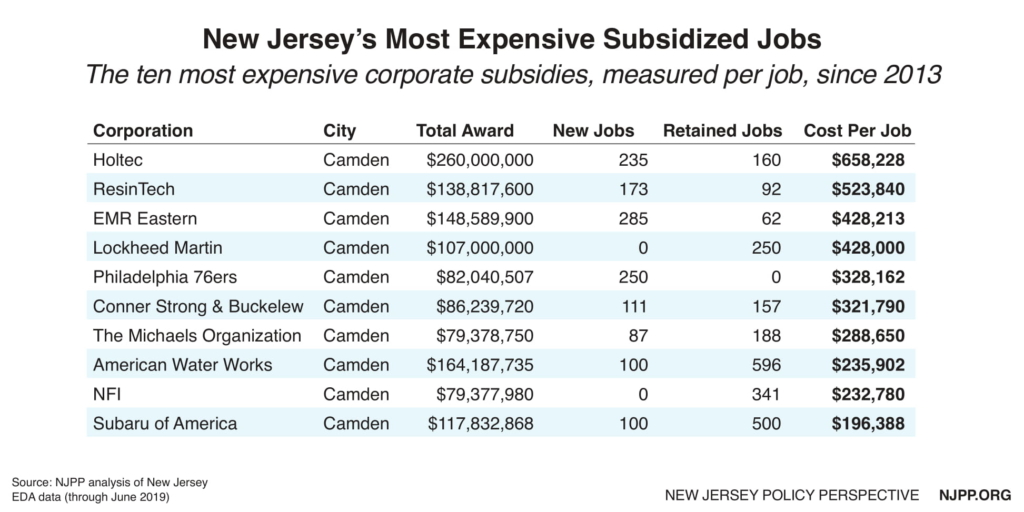

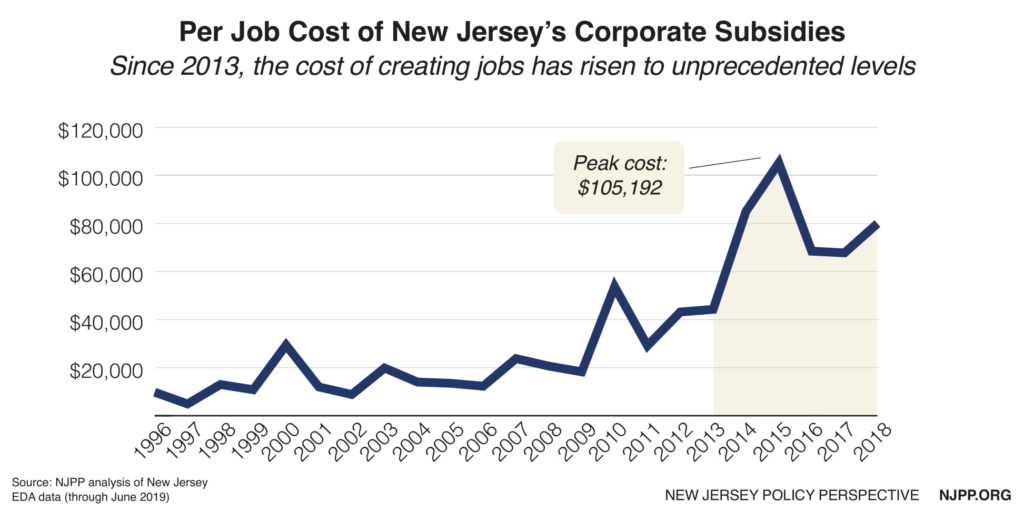

Awards and subsidies of this size are woefully out of sync with economic development strategies in other states. Whereas the average per job cost of corporate tax incentives hovers around $33,000 nationwide, New Jersey’s unrestricted spending spree on subsidies led to a record breaking $105,192 per job price tag in 2015.[i] Today, the cost still exceeds $80,000 per job.[ii] In Camden, where special provisions in the EOA allowed for bonus awards, the average spending on tax subsidies totals a whopping $215,000 per job.[iii] In some deals, New Jersey agreed to tax breaks worth more than half a million dollars per job.

This overreliance on corporate tax subsidies flies in the face of economic development best practices and ignores New Jersey’s precarious fiscal condition. In testimony delivered to a senate committee on economic growth strategies, national experts agreed that corporate subsidies like New Jersey’s have questionable benefits for the public good.

According to Dr. Timothy Bartik, Senior Economist at the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, at least 75 percent of incentives have no effect on job creation.[iv] Worse, corporate subsidies rarely, if ever, pay for themselves because nearly all revenue gained from job creation is offset by necessary public costs used to mitigate its impact. Jackson Brainerd, a policy specialist from the National Conference of State Legislatures, reiterated this position, stating “there is no evidence that the number of tax incentives offered bears any relation to the broader performance of the state’s economy, and there’s quite a bit of evidence that tax incentives often fail to achieve their stated goals and have a negative impact on state fiscal health.”[v]

Of the $11 billion in tax subsidies approved since New Jersey began offering them, an outstanding majority have yet to be redeemed. The state’s biggest subsidy programs — Grow New Jersey Assistance (Grow NJ), Economic Redevelopment & Growth (ERG), and Urban Transit Hub Tax Credit (HUB) — awarded approximately $8 billion in subsidies. Yet fewer than 9 percent of those tax credits have been distributed to corporations that met their qualifying goals, according to the state Comptroller.[vi]

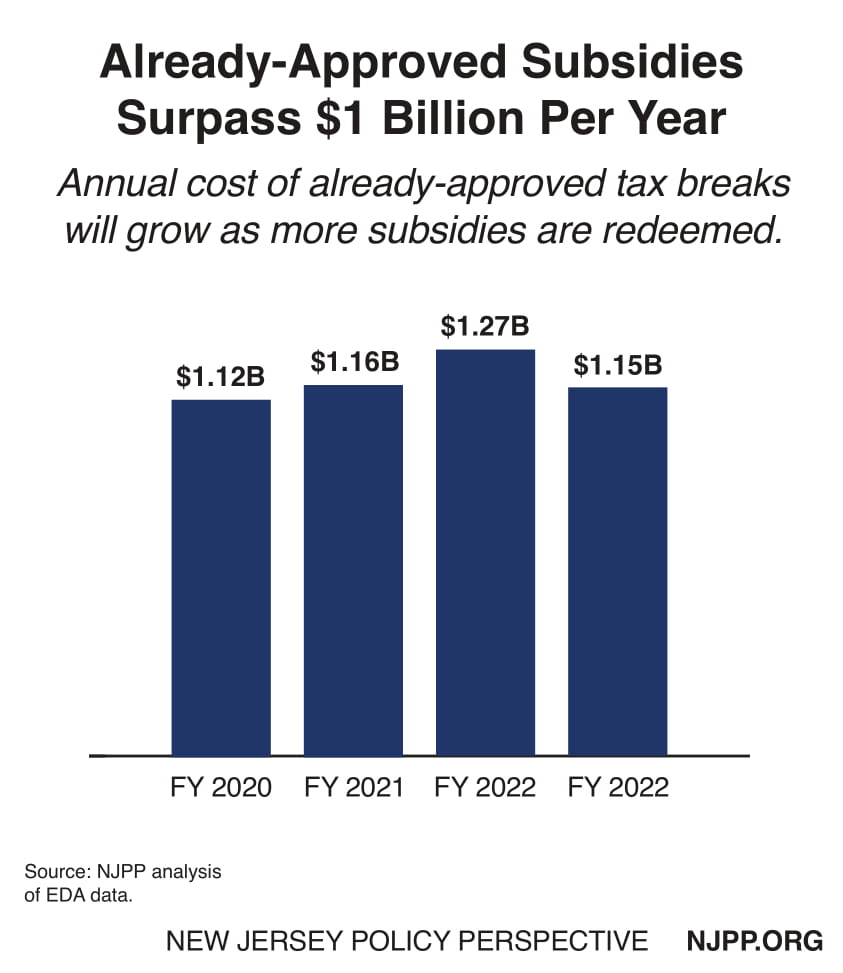

That means the drag on New Jersey’s finances has yet to be fully realized. Starting in fiscal year 2020, already-approved tax breaks are estimated to cost New Jersey over $1 billion annually in foregone tax revenue.[vii] That figure is likely to grow in future years as more subsidies granted under the EOA are redeemed.

A New Approach to Economic Development: 10 Key Reforms

To improve the quality of New Jersey’s corporate incentive programs, it is vital for lawmakers to pursue a more fiscally responsible approach to economic development that reins in the volume and scope of subsidies. This is especially important considering the state’s ongoing struggles meeting its past and current budgetary obligations.

New Jersey should also consider implementing a regional corporate subsidy ceasefire agreement with neighboring states that share a labor market. Modeled after the Kansas City pact, this innovative interstate agreement sets a powerful precedent for the tri-state area, where corporations often threaten to cross state lines in exchange for millions in tax credits.[viii] When tax credits are given to companies that ultimately move within the same metro region, no new jobs are actually created, as they’ve merely shifted to a different address. A ceasefire agreement would end this costly race to the bottom and demonetarize the blackmail tactics made by corporations in exchange for tax subsidies. A resolution introduced by Senator Joe Cryan could be the vehicle for a more regional approach to economic development.[ix]

1. Goals Driven by National Best Practices

Before addressing the design, implementation, and oversight of its tax subsidy programs, policymakers should first take a step back and take a long view of the state’s role in large-scale economic growth. Is the goal of the state’s economic development strategy to encourage new job creation? How important is it to play the defensive strategy of keeping jobs from leaving the state? Should the main focus be on boosting economic activity in distressed areas, increasing the state’s supply of affordable housing, or investing in young, fast-growing companies? Should subsidies be earmarked for sectors that show the greatest potential for growth in the Garden State?

Once the goals are clarified, policymakers would better serve the public good by abiding by the so-called “rule of 98 and 2.”[x] Businesses typically spend less than 2 percent of their total costs on state and local taxes. The other 98 percent consists of variables such as labor, occupancy, raw materials (or other inputs), IT, marketing, administration fees, and logistics. New Jersey should treat their economic development dollars in the same manner: de-emphasize large awards for a tiny percentage of corporations and, instead, invest heavily in the basics that benefit businesses across the state like development of an educated workforce with quality K-12 and higher education, reliable infrastructure, affordable homes, and specialized job training programs.

2. Hard Caps on Annual and Per Job Subsidy Awards

New Jersey has offered corporate tax subsidies as an economic strategy since the 1990s, and though each iteration was slightly different, they always included annual limitations on cost — until the Economic Opportunity Act of 2013. Under the EOA, the job creation program had a spending cap, though it was repeatedly lifted by the legislature. Bypassing such an important cost-control mechanism opened up a Pandora’s Box of already wealthy corporations taking advantage of generous tax breaks with lax oversight. If the Grow NJ program included a hard $200 million spending cap per year, New Jersey would have awarded $4 billion less in tax breaks over a seven-year period — a whopping 74 percent savings.

Research by the Pew Charitable Trusts highlights that well-designed tax subsidy programs utilize annual cost limits to address long-term affordability upfront and keep annual costs more predictable.[xi] Governor Murphy’s proposed subsidy programs feature annual spending caps, though the larger programs allow for some flexibility that could prove costly.[xii] The Murphy administration’s jobs-based program, NJ Forward, has an annual soft cap of $200 million with the option to lift the cap by as much as $100 million. The real estate subsidy program, NJ Aspire, has a spending cap of $100 million allocated through biannual applications, with some large-scale projects excluded from the cap. Three other proposed programs have annual caps of $60 million or less.

To both increase the legislature’s role in oversight and restore the public’s trust in how government invests tax dollars, spending caps should be on the smaller side without exception. Allowing flexibility as proposed in NJ Forward is excessively subjective and vulnerable to the political pressures of a proposed megadeal. Similarly, a proposal introduced by Senator Singleton would give the legislature the authority to enact spending caps on a year-to-year basis for tax credits that foster job creation or retention based on EDA projections.[xiii]

If these programs were instead funded by appropriations, like most government programs, it would give the governor and lawmakers more control of their costs. It would also create another opportunity for lawmakers to understand the size and scope of the state’s corporate tax subsidy programs and hopefully encourage a healthy debate about the right level of funding and how to improve their effectiveness. Although an appropriations process is far more common for cash incentives than it is for tax incentives, it can work for tax incentives, too, according to the Pew Charitable Trusts. For example, in Florida’s budget each year, lawmakers set how much money will be available for several of the state’s programs, including cash and tax incentives. This isn’t a new strategy for New Jersey; the former Business Employment Incentive Program (BEIP) was subject to annual appropriations in the state’s budget.

The removal of spending caps in the EOA also led to skyrocketing per-job costs. New Jersey’s average award per job since the end of 2013 is $81,300. In Camden, the average is $200,570 per job. Taxpayers subsidized 250 new jobs linked to the Philadelphia 76ers new practice facility for an astonishing $328,000 per job, while 395 new and retained jobs at Holtec cost $658,228 each. At such a price, taxpayers can never break even. That is, workers at such firms are never going to pay $300,000 or $600,000 more in state and local taxes than public services they and their families consume. Considering these egregious costs, New Jersey’s outsized subsidy levels should be cut in half, at least, as measured by dollars-per-job. The Murphy administration’s proposal includes a sensible dollars-per-job cap ranging from $2,400 to $6,400 per year, which is more in line with at least 16 other subsidy programs across the country that impose caps of less than $10,000 per job.[xiv] This best practice helps to avoid giving mega-tax breaks to just a few companies without adequate evidence that the economic benefit will eventually pay for them.

3. Shorter Award Timeframes

New Jersey currently allows projects to qualify for corporate tax subsidies that are paid out over the course of 10 to 20 years, which is much longer than necessary and out of sync with best practices. Research shows that corporations are far less persuaded by money that they are promised a decade from now.[xv] Offering shorter timeframes means a state can spend less on subsides and more easily predict when business will earn or use the awarded credits while receiving the same benefits. The NJ Forward program, the Murphy administration’s job creation proposal, includes this best practice by imposing a timeframe of three years with a built-in two-year extension, if necessary.[xvi] The proposal also requires businesses to document performance indicators while committing to maintain their operations in the state for twice as long as their award timeframe. Further, the Murphy administration’s proposed historical preservation and environmental cleanup programs have one-year timeframes. With shorter timeframes, New Jersey can be better assured it is “moving the needle” on corporate decisions while avoiding long-term budget problems.

4. Local Hiring Agreements

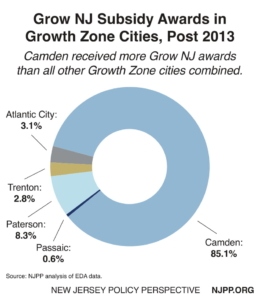

Under the EOA, the EDA awarded large-scale tax subsidies to “distressed municipalities” to encourage investment, business development, and employment in those areas. New Jersey’s designated Growth Zones include Atlantic City, Camden, Passaic, Paterson, and Trenton. However, the overwhelming majority of these awards — over 85 percent — went to Camden without specifically tailored requirements to ensure local hiring.

Thirty-six projects were approved since 2013 without any meaningful guarantee to Camden residents that local hiring would be a priority. Instead, the subsidized jobs were typically filled by workers who commute across city limits, while the vast majority of construction jobs associated with 25 subsidized projects were taken by workers from outside the city.[xvii]

This further debunks the trickle-down philosophy underpinning the state’s economic development strategy. Simply targeting subsidies in a “distressed municipality” does not guarantee jobs, let alone good paying ones, for local residents.

Tax subsidies for distressed local labor markets must be tied to first source hiring agreements and customized job training to encourage prioritized hiring of unemployed and underemployed local residents.

Research demonstrates that this targeted strategy has social benefits that endure even if the initial job is short-lived.[xviii] In other words, efficiently run job training programs may give New Jersey a better return on investment than reducing the tax burden of corporations. The Murphy administration’s proposal offers bonuses in its job creation program to encourage local hiring.[xix] But local hiring should instead be a requirement.

5. Strict Reporting and Evaluation Criteria

Based on the selected findings of the state Comptroller’s audit and the EDA Task Force, major flaws persist in the state’s monitoring of tax subsidy recipients and evaluation of the EDA’s overall effectiveness. In 2007, the state mandated a report — the Unified Economic Development Budget (UEDB) — to provide important and detailed information about larger tax subsidies and the types of jobs they created. That report has never been produced. While there have been annual reports on tax breaks produced since 2010, the UEDB would provide a more comprehensive look at the state’s subsidy programs. The EDA has taken steps to produce a similar annual report, but it is not enough given the mounting evidence of mismanagement, or worse, corruption.[xx] The Treasury Department must release the annual UEDB report going forward.

Policymakers must first assess why New Jersey has a track record of failing to monitor and enforce its performance standards before crafting effective and enforceable reform measures. The assessment criteria in the Murphy administration’s proposal includes annual reporting by award recipients on the number of new and retained jobs, along with their salaries.[xxi] Self-reporting like this should be paired with real-time data from the Departments of Labor and Treasury to ensure accuracy and oversight.

Lawmakers must also fully commit to establishing a regular, independent evaluation process in order to effectively analyze the design, administration, and effectiveness of the state’s subsidy programs. The recent studies from the Bloustein School at Rutgers University and the Comptroller are not enough. Pew’s research shows that states benefit significantly from recurring evaluations. This is evidenced by thirty states utilizing this sort of evaluation process, with many states acting on the findings to reform their tax subsidy programs.

The Murphy administration’s proposal includes a biennial, independently produced report with a detailed analysis of the tax subsidies’ effect on a business’ relocation decision, the return on investment for the award, the impact on the state’s economy, and other metrics based on national best practices.[xxii] However, rather than relying on a sub-contracted college or university for such a report, a biennial performance audit produced by the Comptroller would be much more effective as it is less likely to invoke any concerns over conflicts of interest.

Finally, lawmakers must get a better handle on the budgetary impact of already-approved subsidies, i.e., of cumulative tax credit liabilities. Without this data, policymakers are left in the dark when the costs of tax subsidies begin to rise, leaving them unprepared for increases or ill-equipped to change the design of the programs. Right now, at the request of the Office of Legislative Services (OLS), the EDA voluntarily provides 5-year fiscal impact estimates of already approved awards on the state’s budget.[xxiii] Should OLS cease to ask for this information, there is no guarantee that the EDA will continue to supply such data. This is especially concerning for New Jersey given the enormous long-term obligations the state has incurred since the EOA was enacted. Policymakers would benefit from an annual forecast of the cost of each program in addition to data on maximum liabilities. Not only should this forecast be required by law to ensure transparency, but it should more closely match the lifespan of the approved tax subsidies to generate a better estimate of long-term future revenue losses. A multi-year forecast requirement is not included in the Murphy administration’s proposal.

6. Stronger Net Benefits Test

Lawmakers need to build upon the EDA’s changes to the “net benefits test,” which is the statutory formula used to estimate the economic benefits of tax subsidies. As a basic taxpayer protection, a strong net benefits test restores a sense of fiscal responsibility and realism that has been sorely lacking since the passage of EOA. The EDA’s “net positive benefit” test has since been improved to cover the time period a business commits to maintaining the awarded project. However, there are loopholes that allow projects within a specific place, particularly Camden, to water down this provision.[xxiv]

The clawback formula in the net benefits test has also been improved administratively, but it does not apply to every project administered by the EDA. It is imperative that carve-outs for this provision be eliminated.

The legislation guiding the EDA can be significantly improved to deliver better outcomes for workers and communities with the following recommendations: codify stringent tax subsidy standards for retained jobs, close all job retention loopholes in EOA, and place a cap on the percentage of tax subsidy dollars awarded for job retention (e.g.,10 percent of gross tax credits).

7. Restrict Sale of Tax Credits

It sounds counterintuitive, but most New Jersey tax credits are not claimed by the companies to which they were awarded. Why? Because the “tax credits” are so large, they greatly exceed the companies’ tax liabilities. When this happens, a recipient firm is legally allowed to sell its award to other businesses for cash on a secondary marketIn fact, most recipients of tax subsidies in New Jersey do just that. The buyers are usually large corporations that have substantial tax liabilities and can use the credits, dollar for dollar, to reduce their tax bills. So these “tax credits” are not tax breaks for the recipient companies; they are actually cash gifts to them. Since 2011, over three-quarters of the corporations that received tax credit awards sold their tax credits, and at a significant discount.[xxv] This practice then leaves the state Treasury to contend with front-loaded corporate tax revenue shortfalls; it does not learn of tax credit sales until the new owner files to cash them in.

The sale of tax credits would still be allowed under the Murphy administration’s proposal, but with a nod toward better transparency by making these transactions publicly available on the EDA website.[xxvi] If the ultimate beneficiary of a tax credit award is not disclosed, then the state’s largest tax expenditures for economic development are hidden. In some cases, a 10 percent sales tax would be applied, helping close revenue gaps caused by the companies cashing the credits in. These are important first steps, but more should be done to restrict a practice that benefits corporations more than New Jersey taxpayers. For starters, the 10 percent sales tax should be applied to the sale of all tax credit awards, and documented “bad actors” should be barred from purchasing tax credits on the secondary market (see below).

8. Mandatory Labor Protections

Under the EOA, applicants of Grow NJ were offered a bonus of up to $1,500 per job if the average salary was either more than the existing county average or more than the average salary in one of the Growth Zone cities (Atlantic City, Camden, Trenton, Passaic, and Paterson). Offering bonuses as a way to further an important policy objective, such as creating jobs that pay a living wage, is an insufficient approach. In fact, the EOA had originally mandated that building services workers (such as custodial and security staff) on any project or development that received tax credits could be paid no less than the prevailing wage for that industry or sector. It was the only part of the Economic Opportunity Act of 2013 conditionally vetoed by then-Governor Christie.

A bill introduced by Senator Singleton would reinstate this provision, while the Murphy administration’s proposal goes further, including not just building workers but also construction workers.[xxvii] Still, policymakers should be more proactive to ensure that all new subsidized jobs have salaries that are above existing market averages for the geographic area, industry, or occupation.

Policymakers should also mandate other labor protections that play a key role in fostering a strong and healthy state economy in New Jersey. For example, companies that receive tax subsidies should be required to implement fair work schedules and production quotas, provide affordable healthcare, and guarantee workplace safety standards. These priorities are critical because when workers have rights, wages go up, poverty rates go down, the use of government benefits programs decreases, workers’ safety improves, and economic stability and prosperity prevails.

9. Community Benefit Agreements

The Murphy administration’s reform proposal features bonus structures to encourage community benefit agreements to generate local employment, good paying jobs, innovative technology, incubator development, and more.[xxviii] However, offering bonuses does not go far enough in advancing critical policy priorities.

Lawmakers should eliminate bonus options as a tactic and instead require community benefit agreements for all projects to encourage strong environmental standards, job training, targeted labor protections, affordable housing set-asides, and market-based wage standards. This model allows community groups to have a voice in shaping a redevelopment or job creation project by pressing for community benefits that are tailored to their particular needs. The fulfillment of commitments made to the community by the award recipient would need to be submitted to the EDA in order to certify their compliance with the community benefits agreement.

10. Prohibit Awards to Documented “Bad Actors”

Currently, the EDA has rules in place which prohibit corporations from receiving tax subsidies if they have violated certain state and federal laws. However, the process of vetting applicants properly has proven to be faulty based on recent reports of awards going to corporations that should have been disqualified from the very beginning.[xxix] Again, staff at the EDA need better training to ensure tax dollars are not benefitting bad actors. Additionally, the scope of what constitutes disqualification should be expanded. Senators Cruz-Perez and Singleton have introduced a bill that would deny tax subsidies to businesses that are two years or more delinquent on a previously awarded loan.[xxx] Other types of bad corporate practices that should lead to disqualification include parking profits offshore to avoid federal and state taxes and any violation of federal law in the last five years.

Endnotes

[i] Prepared testimony of Dr. Timothy J. Bartik, Senior Economist, W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research before New Jersey State Senate Select Committee on Economic Growth Strategies, September 2019. https://research.upjohn.org/presentations/60/; NJPP analysis of New Jersey Economic Development Authority public data, accessed via the EDA website. The data is up-to-date through the August 2019 EDA meeting.

[ii] NJPP analysis of New Jersey Economic Development Authority public data, accessed via the EDA website. The data is up-to-date through the August 2019 EDA meeting.

[iii] Ibid 2

[iv] Prepared testimony of Dr. Timothy J. Bartik, Senior Economist, W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research before New Jersey State Senate Select Committee on Economic Growth Strategies, September 2019. https://research.upjohn.org/presentations/60/

[v] Testimony of Jackson Brainerd, Policy Specialist, National Conference of State Legislatures before New Jersey State Senate Select Committee on Economic Growth Strategies in Politico New Jersey, National Experts Recommend Overhauling New Jersey’s Tax Incentive Programs, September 2019. https://www.politico.com/states/new-jersey/story/2019/09/05/national-experts-recommend-overhauling-new-jerseys-tax-incentive-programs-1173192https://www.politico.com/states/new-jersey/story/2019/09/05/national-experts-recommend-overhauling-new-jerseys-tax-incentive-programs-1173192

[vi] State of New Jersey, Office of the State Comptroller, New Jersey Economic Development Authority: A Performance Audit of Selected State Tax Incentive Programs, January 2019. https://www.state.nj.us/comptroller/news/docs/eda_final_report.pdf

[vii] New Jersey Economic Development Authority, Response to Office of Legislative Services Questions in Fiscal Year 2020 Budget Hearings, May 2019. https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/legislativepub/budget_2020/EDA_response_2020.pdf

[viii] The Kansas City Star, “Sometimes common sense does prevail.” Kansas celebrate end of border war, August 2019. https://www.kansascity.com/news/business/article233725152.html

[ix] New Jersey Senate Resolution Number 158, Urges governors of New Jersey, Delaware, New York and Pennsylvania to collaborate on tax incentive agreement similar to Kansas and Missouri’s agreement.

[x] Greg LeRoy, Executive Director, Good Jobs First, Testimony before Governor Murphy’s Task Force on New Jersey’s Economic Development Authority Tax Incentives, July 9, 2019.

[xi] The Pew Center on the State, The Pew Charitable Trusts, Avoiding Blank Checks Creating Fiscally Sound State Tax Incentives, December 2012. https://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/legacy/uploadedfiles/pcs_assets/2012/pewtaxincentivesreportpdf.pdf

[xii] Governor Murphy’s Conditional Veto of New Jersey Senate Bill Number 3901, August 2019. http://d31hzlhk6di2h5.cloudfront.net/20190823/54/bd/95/16/7c81846d765063ebeb8a61c1/S3901CV.pdf

[xiii] New Jersey Senate Bill Number 4063, Establishes award limitations for certain EDA tax incentives related to job creation and retention.

[xiv] Ibid 12; Good Jobs First, Smart Skills versus Mindless Megadeals, September 2016. http://www.goodjobsfirst.org/sites/default/files/docs/pdf/smartskillsversusmindlessmegadeals.pdf

[xv] Bartik, Timothy, J., Who Benefits From Economic Development Incentives? How Incentive Effects on Local Incomes and the Income Distribution Vary with Different Assumptions about Incentive Policy and the Local Economy, 2018. https://research.upjohn.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1037&context=up_technicalreports

[xvi] Ibid 12

[xvii] Philadelphia Inquirer, NJ Tax-break Projects Hired Just 27 Camden City Residents for Construction Jobs, A State Analysis Found, September 2019. https://www.inquirer.com/business/nj-tax-breaks-camden-jobs-construction-economic-development-authority-20190912.html?__vfz=medium%3Dsharebar

[xviii] Bartik in Greg Schrock, Remains of the Progressive City? First Source Hiring in Portland and Chicago, Urban Affairs Review, 2015. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.832.6973&rep=rep1&type=pdf

[xix] Ibid 12

[xx] WNYC News, Norcross Companies in the Crosshairs, May 2019. https://www.wnyc.org/story/norcross-companies-crosshairs/

[xxi] Ibid 12

[xxii] Ibid 12

[xxiii] Ibid 7

[xxiv] P.L. 2013, c.131, New Jersey Economic Opportunity Act of 2013. https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2012/Bills/PL13/161_.HTM

[xxv] The Wall Street Journal, For sale: New Jersey tax credits, July 2018.

[xxvi] Ibid 12

[xxvii] New Jersey Senate Bill Number 60, Modifies certain provisions of EDA incentive programs; requires EDA to provide report with review and analysis of those programs, https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2018/Bills/S0500/60_I1.PDF; Ibid 12

[xxviii] Ibid 12

[xxix] NJ Spotlight, Whistleblower Says Her Former Company Lied in EDA Tax-Incentive Application, March 2019. https://www.njspotlight.com/stories/19/03/28/whistleblower-says-her-former-company-lied-in-eda-tax-incentive-application/; WNYC, A False Answer, A Big Political Connection And $260 Million In Tax Breaks, May 2019. https://www.wnyc.org/story/false-answer-political-connections-millions-tax-breaks/

[xxx] New Jersey Senate Bill Number 1576, Prohibits awarding of economic development subsidy to business if payment of principal and interest on previously awarded loan or loan guarantee is greater than 24 months overdue, https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2018/Bills/S2000/1576_I1.PDF