Introduction

New Jersey’s future prosperity depends on a transportation system that works for everyone. Over generations, communities across the Garden State have come together to support the mobility of New Jerseyans through public transit. The state’s investments in transportation have nurtured economic productivity and improved access to jobs, schools, and other opportunities. Indeed, the state would look quite different without those forward-thinking investments.

While NJ Transit’s diesel bus fleet has been an indispensable tool for so many New Jerseyans, there are significant environmental and public health costs. By electrifying the state’s public bus fleet, New Jersey can reduce the environmental and health harms that arise from the use of diesel buses, including the greenhouse gas emissions that exacerbate climate change; zero emission buses would also contribute to healthier communities, especially for people of color and those living in low-income neighborhoods.[i]Electrifying public buses also provides a reliable and cost-effective option to maintain and expand the state’s transit system through advances in electric bus technology and rapid declines in battery costs.[ii]

This report examines the important benefits of public transit, particularly for people of color and low-income populations. It then describes the environmental and public health perils of a diesel-based fleet and reviews the environmental and health benefits of electric buses. The report also provides the major costs to and long-term savings of electrifying NJ Transit’s bus fleet, as articulated within the targets of the Electric Vehicle Law (N.J.S.A. 48:25-3). Finally, the report offers funding recommendations along with recommendations for a smoother and more equitable transition from diesel to electric public buses.

Public Transit as a Public Good

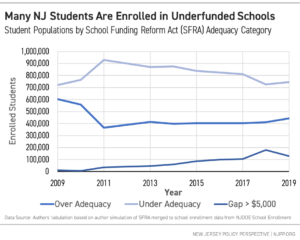

Hundreds of thousands of New Jersey residents across the state use and rely on public transit on a daily basis.[iii] Transportation connects people to jobs, medical appointments, grocery stores, child care, education, and more. During Fiscal Year 2019 alone, riders took 267.3 million trips on public transit in New Jersey, with more than half of those trips, or 141.2 million, taking place on public buses.[iv]

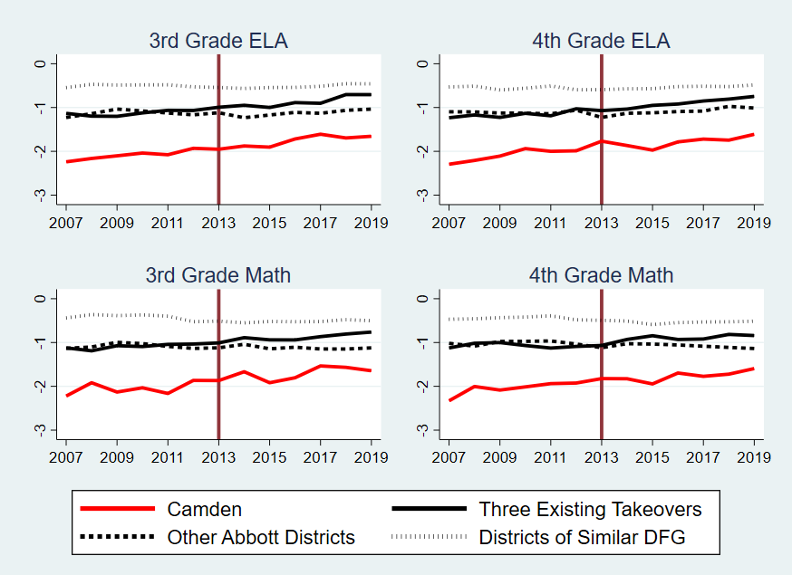

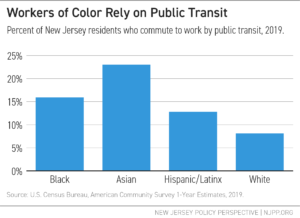

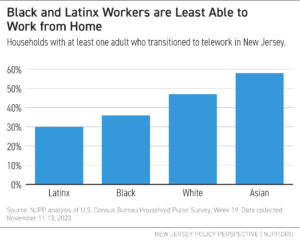

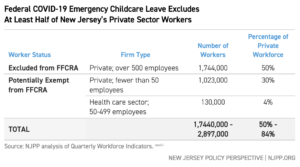

Yet, structural inequities shape — and are shaped by — transit access and use. On the one hand, low-wage jobs, low rates of car ownership, and the “digital divide” mean that some people use transit instead of working from home or driving cars to get where and what they need. For instance, households of color, particularly Black households, are less likely to have access to a vehicle as compared to their white counterparts.[v] And in cities with higher concentrations of people of color, like Jersey City and Newark, households are more likely to lack access to a vehicle compared to households in smaller cities.[vi] On the other hand, as this report discusses below in Section III, public transit, as it exists now, both highlights ー and can exacerbate ー other structural inequities, such as those in public health. Simply put, people of color disproportionately rely on public transit.

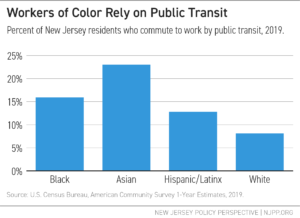

Black and Asian workers are almost two and three times as likely, respectively, as white workers to commute to work by public transit; Hispanic/Latinx workers are 1.5 times more likely. Specifically, 8.1 percent of white workers use public transit, while 15.9 percent of Black workers, 23.0 percent of Asian workers, and 12.8 percent of Hispanic/Latinx workers commute using public transit.

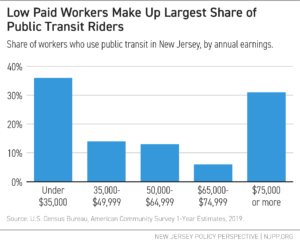

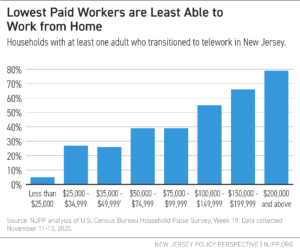

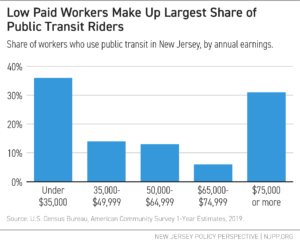

Trends by earnings are similar. Low-income workers are more likely to commute to work by public transit. Over the last 5 years, more than about 36 percent earned $35,000 or less.

Alternatively, over the past 5 years, workers earning $75,000 or more—about 30 percent—use public transit as their primary source of transportation, emphasizing the importance of transit for all income groups.

Mobility through public transit has remained vital during the COVID-19 pandemic. Commuters, many of whom are front-line workers, are using public buses at only a slightly lower frequency as compared to pre-pandemic travel, according to the NJ Transit Customer Travel Survey.[vii] In addition, about 90 percent of these riders have a household income of $75,000 and below, with 10 percent holding more than $75,000 in household income.[viii]

The Environmental and Health Effects of Public Transit

Public transit carries environmental and public health benefits by reducing the number of vehicles on the road, improving air quality, and alleviating traffic congestion and noise.[ix] Transit use supports the growth of more active communities, reduces people’s time spent sedentary in cars, and, as a result, reduces chronic illnesses associated with the sedentary nature of private transit, non-ambulatory commuting.[x] Public health benefits from public transit also result from the increased access to employment, health care services, social services, and food.[xi]

Although public transit positively contributes to environmental and public health outcomes, transit operations also generate negative impacts, which electrification of the bus fleet can offset or eliminate.

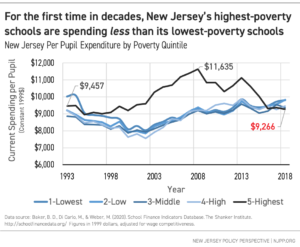

Emissions from mobile sources such as cars, trucks, and buses represent the largest share of greenhouse gas emission origination (42 percent) in New Jersey.[xii] Additionally, the vast majority of buses are diesel-powered, and the diesel exhaust emitted by buses and other heavy duty vehicles is a dangerous pollutant that worsens and triggers health problems.[xiii] Older buses deploy fewer diesel emission control technologies, and aging bus fleets have greater diesel emission impacts, particularly on the communities in which they operate.[xiv] The service life of a typical NJ Transit bus is about 12 to 13 years, with some buses approaching 20 years in age.[xv]

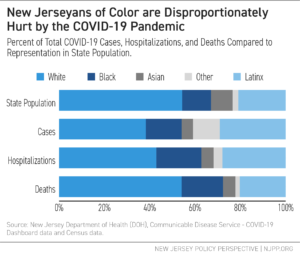

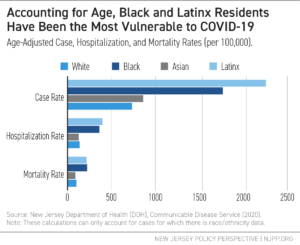

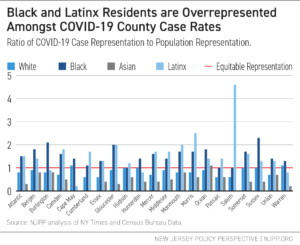

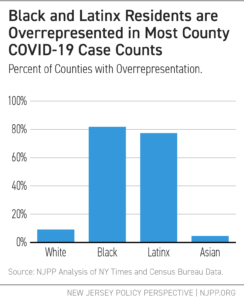

Particulate matter, which are aerosolized solid and liquid pollutants, can harm one’s lungs, heart, and brain.[xvi] New research links this type of pollution to the development of serious diseases, such as dementia.[xvii] What’s worse, studies have also shown that such air pollution can lead to premature death.[xviii] Premature deaths due to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) from roads alone claim up to 2,420 lives every year in New Jersey.[xix] Further, people with COVID-19 who live in areas of high air pollution are more likely to die from the disease, according to Harvard University’s School of Public Health.[xx] And hot spots for the virus are located in predominantly low-income Black neighborhoods.[xxi]

The harmful environmental and public health effects of diesel bus pollution disproportionately harm Black and Brown communities across the nation.[xxii] Bus idling tends to occur more often in these areas, as well.[xxiii] Further, people who live in these communities often live in close proximity to other large and small sources of pollution, as well as old abandoned, contaminated sites, which can pose risks to public health and the environment.[xxiv] This is largely a result of residential segregation, which is caused by structural, institutional, and individual racism. As a result of housing exclusionary housing policies, people of color are often concentrated in neighborhoods that are disempowered and marginalized, both politically and financially.[xxv]

Thankfully, New Jersey is focused on improving air quality by prioritizing the implementation of electric buses. Electric buses can reduce emissions of diesel exhaust, particulate pollution, and other pollutants, improving air quality in communities.[xxvi] For instance, electric buses can reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 75 percent, though this amount is dependent on the source of electricity used to charge buses.[xxvii] Overall, an electric bus eliminates approximately ten tons of nitrogen oxides and 350 pounds of diesel particulate matter over its typical 12-year lifespan.[xxviii] If emissions of diesel pollution in city neighborhoods were curtailed, then urban communities, particularly communities of color and low-income communities, could reap the benefits of public transit without suffering the public health costs.[xxix]

State Policies and Goals around Electrifying Public Buses

In 2020, New Jersey implemented N.J.S.A. 48:25-3 — which will be referred to as the “Electric Vehicle Law” in this report — to set forth targets and various incentives to increase electric vehicle use, spur infrastructure development, and ultimately reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the transportation sector. Part of this legislation directs NJ Transit to purchase battery-operated public buses, with the goal of buying only zero-emission public buses by 2032.[xxx]

NJ Transit Electric Vehicle Purchasing Goals and

Targets Outlined in the Electric Vehicle Law

|

| Goal |

Target Date |

| 10% |

December 31, 2024 |

| 50% |

December 31, 2026 |

| 100% |

December 31, 2032 |

|

NJ Transit’s current ten-year strategic plan and five-year capital plan dictate how the state phases in the purchases of electric buses, develops related infrastructure, and phases out diesel-fueled buses.[xxxi] The strategic plan presents a roadmap of strategic choices and critical investments, while the capital plan identifies projects, budget considerations, and scheduling.

NJ Transit is currently developing plans for electric bus deployment and to upgrade infrastructure, including the acquisition of specific dispatching technologies to ensure high-quality bus service when the rollout occurs.[xxxii]

Regarding electric bus rollout, NJ Transit’s “Phase 1” plan will replace 68 40-ft diesel transit buses that are currently in service with 68 40-ft electric buses and introduce 11 60-ft electric articulated buses, plus an additional 21 electric articulated buses dedicated for a new bus garage in northern New Jersey.[xxxiii] Later phase details are unknown to the public at the moment, but the estimated total cost to fully electrify the bus fleet is about $5.7 billion by 2040.[xxxiv]

As for bus garages, which will need to be zero-emission ready and capable of storing and maintaining electric buses, NJ Transit plans to construct two additional garages, completely replace four current garages, and modernize the remaining 12 garages, all for an estimated total cost of $2.65 billion.[xxxv] Currently, the transit authority operates 16 bus garages that range between 20 and 120 years old, none of which have been majorly renovated since 1998.[xxxvi]

The two new bus garages, referred to as the “Northern Bus Garage” and “Second Northern Bus Garage,” will likely be located near the Meadowlands. Although NJ Transit has not acquired land for the projects yet, the facilities are expected to include modern features such as solar panels, up-to-date fleet and maintenance equipment, and modifications for electric buses.[xxxvii] Estimated costs for these garages are approximately $928 million, plus the cost of land acquisition.[xxxviii]

NJ Transit also plans to implement a separate Bus Garage Replacement Program, contingent upon receiving necessary funding. The program would replace the four oldest bus garages: the Market Street Garage (Paterson), Oradell Garage (Oradell), Big Tree Garage (Nutley), and Fairview Garage (Fairview). The estimated costs for this program are $609 million.[xxxix] The costs to modernize or replace bus garages include charging infrastructure, unit substations, and maintenance equipment.

Finally, NJ Transit will modernize the remaining 12 bus garages to accommodate electric vehicle charging infrastructure and electric buses. The estimated costs of this modernization process total approximately $1.12 billion.[xl]

NJ Transit Garage Construction and Renovation Plans

|

| Garage Project |

Location |

Time Frame |

Estimated Costs |

Construct 2

New Garages |

Northern Bus

Garage, TBA |

5 years |

$536 million |

Second Northern Bus

Garage, TBA |

9 years |

$392 million |

Replace 4

Old Garages |

Paterson, Oradell, Nutley, and Fairview |

11 years |

$608.5 million |

Modernize 12

Remaining Garages |

Around the State |

11 years |

$1.115 billion |

| Total |

|

|

$2.65 billion |

Source: NJ Transit Capital Plan Financial Summary (Unconstrained) and Economic Impact Study of NJ Transit’s Five Year Capital Plan. |

|

Three major challenges arise with the rehabilitation, modernization, and replacement of existing garages:

- The temporary loss of capacity on bus lines, since each garage needs to be taken out of service. This loss of capacity can put a strain on those who rely on bus transportation, particularly low-income individuals.

- Some garages may not be able to accommodate the configuration and size of new, larger buses and electric bus fleet upgrades across all neighborhoods due to the narrowness of some streets. However, NJ Transit is conducting analyses at the four locations that will be modernized, identifying routes that can accommodate anticipated electric bus configurations.

- The path to determining and securing funding sources for the garage plan rollout, including the purchasing of buses and the development of necessary infrastructure, remains unclear.

NJ Transit’s Timeline to Transition to Electric Buses is Misaligned with Goals Set in the Electric Vehicle Law

The NJ Transit capital plan, published in June 2020, estimates that the total cost to replace the entire diesel fleet will be about $5.7 billion and that a 100-percent fleet transition will not be achieved until 2040, eight years past NJ Transit’s original goal.[xli] The Electric Vehicle Law specifies a target date for 100-percent electric bus purchases by December 2032. Further, while NJ Transit’s five-year $11.21 billion capital plan was approved, with $1.4 billion for projects in the plan for Fiscal Year 2021 alone, there is no clear funding source for the $5.7 billion needed to implement the diesel bus replacement program.[xlii]

There’s also potential misalignment under NJ Transit’s current strategic plan, too. Through 2026, the transit agency plans to devote about $15 million towards the purchase of electric buses,[xliii] which is a small fraction of the $1.68 billion needed for the implementation of bus purchases and deployment in that time.[xliv] This indicates that less than one percent of bus purchases over the next six years would be electric, which drastically misses the electric bus vehicle goals outlined in the Electric Vehicle Law.[xlv]

However, NJ Transit plans on creating a bus electrification master plan by 2022. As the economic crisis exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic continues, the capital and strategic plans may see further changes as well.

Electric Buses: Costs and Savings

To better inform ongoing and future conversations around bus electrification efforts in New Jersey, this section examines the major costs and savings of replacing the entire active fleet with electric buses by the legislative target of 2032.

Bus Purchasing Costs and Savings

NJ Transit has approximately 2,183 active diesel buses in its entire fleet.[xlvi] To accommodate current ridership, the transit authority would need 1.2 electric buses for every diesel bus.[xlvii] As such, about 2,620 electric buses would be needed to replace the current diesel fleet. The approximate cost for a 40 ft-electric bus is about $749,000,[xlviii] whereas a 40-ft diesel bus costs about $500,000.[xlix] Therefore, it would cost about $1.96 billion to replace all diesel buses with electric ones.

Upfront Costs of Electric and Diesel Bus Fleets

|

| Bus Type |

Cost per Bus |

Total Cost of Fleet |

Electric Bus with

450 kWh Batteries

(2,620 buses) |

$749,000 |

$1.96 Billion |

Electric Bus

without 450 kWh Batteries

(2,620 buses) |

$553,000 |

$1.45 Billion |

Diesel Bus Fleet

(2,183 buses) |

$500,000 |

$1.10 Billion |

Source: Proterra; American Public Transit Association. |

|

However, there are opportunities for significant savings. For instance, the costs of electric buses are expected to decline, given the trend of gradually decreasing purchase prices and the increased availability of battery leasing options.[l] For example, the price of electric buses purchased by Foothill Transit, in the San Gabriel Valley of Greater Los Angeles, declined from $1 million in 2009 for a 35-ft electric bus to $789,000 in 2015 for a 40-ft bus.[li] Some transit agencies have even purchased electric buses for less than $700,000 when bought in bulk. For example, LA Metro purchased 60 electric buses at the price of $686,000 in 2017 from Build Your Dreams (BYD), another electric bus manufacturer.[lii] What’s more, new manufacturers are designing lighter buses at potentially lower costs. For instance, Arrival, a U.K.-based electric vehicle startup with a factory in New Jersey, claims that their electric buses will be priced much like diesel buses, significantly lowering the total cost of ownership.[liii]

The cost of batteries, which are approximately a quarter of the total cost of an electric bus, are declining by 5 to 10 percent each year.[liv] And since 2010, battery prices have fallen by 79 percent.[lv] In 2017, lithium-ion battery prices were $209/kWh, down significantly from $1,000/kWh in 2010.[lvi]

As the cost for electric batteries continues to decline, battery-leasing options are also becoming more available.[lvii] This method allows NJ Transit to pay for batteries slowly over the lifespan of the electric bus. For example, a Proterra electric bus with batteries costs approximately $749,000, whereas one without batteries costs about $553,000.[lviii]

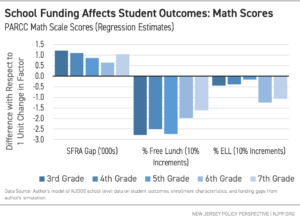

Maintenance Costs and Savings

Currently, NJ Transit spends approximately $263 million per year on maintenance for diesel buses.[lix] However, there can be significant savings with electric buses, which result from no longer needing to address mechanical service required by an internal combustion engine (ICE), lack of oil and filter changes, and fewer tires and brake pad replacements.[lx] Transitioning to electric buses can potentially save about $81,500 per bus, per year, or $213.7 million for the electric bus fleet, per year.

Maintenance Costs and Savings, Electric and Diesel Buses

|

| |

Diesel |

Electric |

| Cost per Mile |

$2.93 |

$0.55 |

| Cost per Year |

$263.1 Million |

$49.4 Million |

| Savings per Bus |

N/A |

$81,500 |

| Savings per Bus/Year |

N/A |

$213.7 Million |

Source: NJ Transit; U.S. PIRG. |

|

Fuel Costs and Savings

With the conversion to electric buses, NJ Transit can expect major savings on fuel costs, as electric buses will not need diesel fuel, which costs New Jersey about $2.81 per gallon, or about $61.6 million per year to fuel its diesel fleet. The electric cost per bus is about $0.19 per mile, which would cost about $17.1 million per year. Overall, the state could potentially save approximately $44.5 million per year in fuel costs.

Fuel Costs and Savings, Electric and Diesel Buses

|

| |

Diesel |

Electric |

| Cost per Mile |

$2.81 |

$0.19 |

| Cost per Year |

$61.6 Million |

$17.1 Million |

| Savings per Bus/Year |

N/A |

$44.5 Million |

Source: NJ Transit; U.S. PIRG. |

|

Other Costs

Charging Infrastructure

In addition to the costs mentioned above, electric buses come with charging infrastructure costs. However, costs for each charger installation are site-specific and costs can vary significantly depending on site characteristics.[lxi] While NJ Transit will most likely pursue a mix of fast chargers, slow chargers, and overhead charging stations — in the same way other transit agencies across the nation that are implementing the rollout of electric buses have[lxii] — the transit authority will need to conduct a technical route analysis to determine its charging infrastructure needs. This kind of assessment considers rider demand, location, and duration of the pre-existing bus routes. For example, King County Metro Transit’s charging infrastructure cost for a fast charger serving four electric buses is an estimated $144,000, and for a slow-charger serving two electric buses, $34,000.[lxiii] In addition to chargers, the installation for supporting infrastructure will also need to take place. Transit agencies report that supporting infrastructure, like an overhead direct current (DC) charging pantograph, may cost between $80,000 to $110,000 per unit.[lxiv]

Training

A transition to electric buses will require training for operators and maintenance workers. While a bus manufacturer like Proterra provides free initial training for operators and maintenance workers,[lxv] the state will need to offer more robust opportunities for workers to train and learn. Currently, NJ Transit’s annual maintenance and operator training for diesel buses costs $1,500,000 and $3,900,000, respectively.[lxvi] As the state procures more electric buses, training will continue for bus operators and maintenance workers on remaining diesel buses, while simultaneously building the capacity for bus operators and maintenance workers who will transition to electric bus operations.

Other Savings

Health Savings

Harmful emissions increase the incidence of illnesses and respiratory diseases, which impose healthcare costs. Conversion to electric buses is estimated to reduce hospitalization and emergency room costs, as well as the costs of missing work.[lxvii] For instance, residents in Chicago and New York City can expect an average of $55,000 and $150,000 in health savings per electric bus per year, respectively, once their city’s fleets are fully electrified.[lxviii] Further, using the same methodology, D.C. residents should expect about $8 million per year in healthcare savings from electrifying the Metropolitan Area Transit bus fleet.[lxix]

Greenhouse Gas Savings

Conversion to electric buses brings greenhouse gas savings, which are generally monetized using the social cost of carbon. Specifically, this cost measures the economic harm from climate change — such as extreme weather events, the spread of disease, food insecurity — on businesses, families, and governments. These impacts are expressed as the dollar value of the total damages from emitting one ton of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.[lxx] The savings accrued through carbon reduction from electric buses is about $3,000 per bus per year.[lxxi] For New Jersey, this means the state can expect around $8 million greenhouse gas savings in a single year from the electric bus fleet and about $95.9 million over the 12-year lifespan of electric buses.[lxxii]

Recommendations to Help Offset Costs to New Jersey’s Electrification Efforts

This section explores potential funding opportunities from state, regional, and federal sources to support NJ Transit’s bus electrification efforts.

State-Level

Highway Widening Funds

In June 2020, Governor Murphy approved plans to expand the NJ Turnpike, the Garden State Parkway, and the Atlantic City Expressway in the Pinelands, costing an estimated $16 billion.[lxxiii] However, advocates are calling to dedicate these funds to mass transit and bus electrification as expanding highways encourages more automobile travel and worsens congestion — increasing emissions in overburdened communities.[lxxiv] By putting more funding into mass transit, New Jersey can better support commuters, specifically essential and front-line workers who rely on NJ Transit’s daily bus services, and reduce air pollution from transportation.

Clean Energy Program Funds

The state frequently diverts Clean Energy Program funds to support NJ Transit operations.[lxxv] However, transit operations are not in line with the fund’s purpose, which is to offer financial incentives, programs, and services to help save energy, money, and the environment for residents, businesses, and local governments.[lxxvi] If the state insists on continuing to use these funds, they would be better allocated to bus electrification, which is more in line with the fund’s mission.

To limit these diversions and leave more funds available in NJ Transit’s capital budget for electrification projects, the state should use the annual $375 million (gradually increasing to $525 million per year) that the Commissioner of the state Department of Transportation pledged to give to NJ Transit’s operating budget from the NJ Turnpike Authority.[lxxvii] Currently, the transfer is set at $129 million because the balance was put into escrow; however, this should be available sometime in Fiscal Year 2022.[lxxviii]

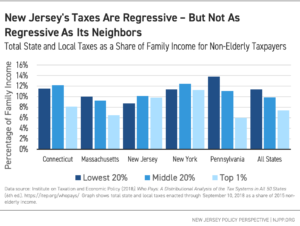

Progressive Taxation

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and the current recession, more revenue will be required to support important investments. While not all new revenue sources would be dedicated to public transit, growing the proverbial pie would help free up other resources for important issues that certainly include transit. Thankfully, the millionaires’ tax, which raises the top income tax rate to 10.75 percent for incomes over $1 million, was passed in September 2020.[lxxix] This tax is expected to bring about $400 million for Fiscal Year 2021 reaching up to $450 million each year thereafter.[lxxx] However, more options must be considered.

New Jersey has the opportunity to restore its sales tax to seven percent and modernize it to include more services, especially those used by higher-income households, like chartered flights, interior decorating, and limousine services. Additionally, the state can restore the estate tax with a higher threshold that would help it regain the lion’s share of the revenue it previously collected while ensuring that the wealthiest heirs pay their fair share at the state level. Reinstating the tax on estates worth more than $1 million would recoup 93 percent of the tax revenue that the state formerly collected from this source.[lxxxi] The overall revenue collected can enhance public services for New Jersey residents, and the funding of electric buses, electric bus garages, and the requisite charging infrastructure should be a top priority.

Regional-Level

Transportation and Climate Initiative Program (TCI-P)

TCI is a regional collaboration of Northeast and Mid-Atlantic States and the District of Columbia that seeks to improve transportation, develop the clean energy economy, and reduce carbon pollution from the transportation sector.[lxxxii] The states have proposed a “cap and invest” model, TCI-P, where an increasingly strict limit would be placed on carbon dioxide pollution (CO2) produced by fuel companies. Companies would purchase “pollution permits” through regular auctions to cover the amount of pollution they plan to emit. The proceeds generated would be divided amongst participating states and invested in programs such as increased public transit, active transportation like walking and biking, and electrifying vehicles. Supply and demand determine the price of these permits, and the program would allow a company to buy more permits if they need a higher clearance to pollute or sell extra pollution permits for a profit.

Preliminary revenue estimates from the TCI-P for New Jersey, based on the memorandum of understanding (MOU) released in December 2020 between four participating jurisdictions,[lxxxiii] indicate $236 million in 2023, growing to $339 million in 2032, and with a cumulative amount of $2.875 billion over 10 years. Realizing this revenue will require legislative action, which has not yet begun. However, New Jersey remains at the table for the development of this program.

While this can be a significant funding source, there are concerns from overburdened communities — who often bear the brunt of air pollution from transportation — and other advocates as to how much pollution TCI-P will reduce and how the funds will be spent. Market-based programs, like TCI-P, can only limit the total emissions, not guarantee pollution reduction in any specific community, like those most harmed.[lxxxiv] However, through the MOU and the recently released draft model rules,[lxxxv] states are committing to invest no less than 35 percent of proceeds to ensure that overburdened and underserved communities benefit equitably from clean transportation projects and programs. In addition, the TCI-P states commit to establish an Equity Advisory Body — composed of diverse stakeholder groups, with a majority of members representing overburdened and underserved communities — or designate an existing body that meets this description, to advise on decision-making and equitable outcomes for TCI-P. While this stated intention is important, ultimately, an MOU or draft model rules cannot require participating states to prioritize funding or pollution reductions in overburdened communities. Therefore, legislation would need to be explicit about reducing the harms in the communities most harmed by air pollution.

Federal-Level

Federal Grants

The Volkswagen Environmental Mitigation Trust allocates funding to states to use for defined eligible projects that reduce Oxides of Nitrogen (NOx) as well as support the expansion of zero-emission vehicle adoption.[lxxxvi] Specifically, this funding can be used to purchase electric buses and invest in charging infrastructure. NJ Transit has already been awarded $8 million to purchase eight electric buses in Camden;[lxxxvii] in total, New Jersey’s allocation under the federal settlement was $72.2 million.[lxxxviii]

In addition, the U.S. Department of Transportation offers grants to states to support public transit. For instance, NJ Transit was granted about $7 million in funding in Fiscal Year 2020 to purchase new electric buses for service expansion purposes through the Federal Transit Administration’s (FTA) Low or No-Emission (Low-No) Grant Program.[lxxxix]

Other grant opportunities from the U.S. Department of Transportation include the FTA’s Bus and Bus Facilities Grant Program, which will provide a combined $464 million to grantees.[xc] Under this grant for FY 2020, New Jersey received $14.7 million to modernize the Wayne Bus Garage.[xci] There’s also the Better Utilizing Investments to Leverage Development (BUILD) Transportation Discretionary Grant Program, which provided a combined $1 billion to grantees in 2020.[xcii]

Other Recommendations for a More Equitable Transition

This section offers recommendations for a smoother and more equitable transition to electric bus infrastructure.

Energy and Electricity Resiliency

Energy resiliency is having a reliable, regular supply of energy and measures in place to minimize disruptions to energy service, such as power failures or state of emergencies.[xciii] Specifically, NJ Transit can strengthen resilience through the following:

- Energy Reliability: Many factors can affect bus mileage, such as temperature and the number of stops, which can affect the reliability of electric buses during an emergency. During the procurement process, NJ Transit can test vehicles’ battery capacity in an operational setting to understand resiliency needs in advance, similar to how the Chicago Transit Authority operates.[xciv]

- Electric School Buses: Electric school buses with Vehicle-to-Grid capability have the capacity to both recharge their battery and feed energy back to the grid. At the University of California San Diego, electric vehicles are becoming a part of the campus’s electric grid during the day, in order to support peak energy usage.[xcv] NJ Transit can work with school authorities to maximize electric resiliency when electric school buses begin to see implementation in New Jersey.

NJ Transit has been able to mobilize its diesel bus fleet during challenging events in the past, such as the attacks on September 11th in 2001 and the difficulties during Hurricane Sandy in 2012. Still, it will be more challenging to maintain energy storage for electric buses in statewide emergencies. With just 42.6 megawatts of capacity installed in 2019,[xcvi] New Jersey has a long way to go to achieve its goals of 600 megawatts of energy storage by 2021, and 2,000 megawatts by 2030, as required by the Clean Energy Act.[xcvii]

Coordination with Other Agencies

NJ Transit should coordinate with the following as it transitions to an all-electric bus fleet:

- NJ Board of Public Utilities (BPU): BPU and NJ Transit can work together to roll out electric buses, particularly around bus depot upgrades and charging infrastructure.

- New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA): NJ Transit could potentially coordinate with MTA to share costs of charging infrastructure. NJ Transit operates in Manhattan through New York’s Port Authority Midtown Bus Terminal and the authorities can ensure that they can charge buses on each other’s grids.

- Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANYNJ): NJ Transit and PANYNJ should share information concerning use of technology and other lessons learned as PANYNJ rolls out electric buses. They could also potentially share the costs of the charging infrastructure by using each other’s grids, particularly since PANYNJ has plans to redesign their bus terminal in Manhattan, the busiest bus terminal in the country, with charging equipment for electric buses.[xcviii]

- New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (DEP): DEP, in coordination with NJ Transit, should measure and oversee the effects of electric buses on air quality, especially in overburdened communities. While DEP already operates 30 air monitoring stations across the state, New Jersey can better maximize its monitoring network, much like Utah does. The Utah Department of Environmental Quality’s Division of Air Quality uses a variety of tools to address air pollution, such as permit conditions, air-quality research and planning, and enforcement actions.[xcix] By tying monitoring alerts to the pollution in neighborhoods, a concentrated effort can be made to reduce pollution across the state, while also identifying areas where electrification efforts are needed the most.

Coordination with Communities

NJ Transit should make the electric bus implementation process transparent and inclusive by holding regular meetings with trusted community leaders and community-based organizations, like Ironbound Community Corporation and Make the Road New Jersey. This will ensure that the implementation’s progress is shared directly with the most impacted people and communities on a regular basis.

Further, NJ Transit should prioritize outreach campaigns in various languages to bring awareness and information about bus electrification efforts. Many people in New Jersey rely on bus transportation for their livelihoods. Therefore, the agency should communicate safety, affordability, benefits to health and the environment, and how those benefits pertain to each community.

Coordination with Transit Workers

The state should support workforce retraining, as electrification requires training in new technology, placement in quality jobs for existing transit workers, and apprenticeships for incoming transit workers. Re-employment and training programs can also be used to structure certifications and ensure that new electric vehicle-related opportunities do not undermine the existing skills that workers have or erode quality standards for the existing workforce.

In addition, safety training and precautions must be prioritized for transit workers. NJ Transit, along with the New Jersey Amalgamated Transit Union (ATU), should ensure that bus manufacturers redesign airflow on buses, especially during health pandemics. In 2020 alone, 15 NJ Transit workers died from COVID-19.[c] Further, there should be more investment in safety training to include an overview of hazards associated with battery chargers, harms associated with hydrogen fuel cells as compared to conventional fuels, battery-specific safety hazards, such as electrocution, arcing, and fires from short circuits, and more.[ci]

Acknowledgments from the Author

To the endowment bestowed through the Kathleen Crotty Fellowship and The Energy Foundation, thank you for funding my research and empowering me to learn about such a critical development in the state’s transportation sector.

A sincere thank you to every single person I spoke with while writing this report, beginning with Dan Fatton, Doug O’Malley, and Nat Bottigheimer. I truly appreciate our meaningful conversations and your patience with me.

Thank you to representatives from NJ Transit, ChargeEVC, Proterra, Tri-State Transportation, New Jersey Board of Public Utilities, Amalgamated Transit Union, Rutgers University, Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, Clean Water Action, Jobs to Move America, New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Make the Road – New Jersey, Ironbound Community Corporation, and urban planners from across the nation. Your advice, insight, and expertise were invaluable.

Thank you to everyone at New Jersey Policy Perspective — Sheila, Louis, David, Brittany, and Vineeta — for being the most supportive colleagues. A special shout out to Brandon McKoy, who always took the time to provide me with his guidance. He truly leads with a vision like no other, grounded in equitable solutions and amplifying the voices of all New Jerseyans.

And finally, thank you Nicole Rodriguez. You are the best mentor and boss I could ever ask for. I am forever indebted to you. Thank you for being patient. I have learned so much from you, and I know you will be a lifelong mentor.

Endnotes

[i] U.S. PIRG Education Fund, Environment America Research and Policy Center, and Frontier Group. (2019). Electric Buses in America: Lessons from Cities Pioneering Clean Transportation. Page 10. https://uspirg.org/sites/pirg/files/reports/ElectricBusesInAmerica/US_Electric_bus_scrn.pdf; Ernani F. Choma, John S. Evans, James K. Hammitt, José A. Gómez-Ibáñez, John D. Spengler. (2020). Assessing the health impacts of electric vehicles through air pollution in the United States, Environment International, Volume 144, 2020, 106015, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.106015.

[ii] U.S. PIRG Education Fund, Environment America Research and Policy Center, and Frontier Group. (2019). Electric Buses in America: Lessons from Cities Pioneering Clean Transportation. Page 4. https://uspirg.org/sites/pirg/files/reports/ElectricBusesInAmerica/US_Electric_bus_scrn.pdf

[iii] U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey. (2019). 1-Year Estimates, share of workers who use public transportation by yearly earnings, 16 years and over, New Jersey

https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=earning&text=transportation&t=Income%20and%20Poverty&g=0400000US34&tid=ACSDT1Y2019.B08119&hidePreview=true

[iv] 267.3 million refers to unlinked bus trips. New Jersey Transit. (FY 2019). Facts at a Glance. https://d2g63oyneaimm8.cloudfront.net/sites/default/files/pdfs/FactsAtaGlance.pdf

[v] National Equity Atlas. (2018). Car access: Everyone needs reliable transportation access and in most American communities that means a car. New Jersey data. PolicyLink. https://nationalequityatlas.org/indicators/Car_access#/?geo=02000000000034000

[vi] National Equity Atlas. (2018). Car access: Everyone needs reliable transportation access and in most American communities that means a car. New Jersey data. PolicyLink. https://nationalequityatlas.org/indicators/Car_access#/?geo=02000000000034000

[vii] Frontline workers are workers within essential industries who must physically show up to their jobs, such as in hospitals, food service, and in transportation.

NJ Transit. (2020, June). Board Operations and Customer Service, Public Committee Meeting, June 26, 2020. Customer Travel Survey. Page 33.

[viii] NJ Transit. (2020, June). Board Operations and Customer Service, Public Committee Meeting, June 26, 2020. Customer Travel Survey. Page 37. 90 percent does not include bus trips to New York but in North Jersey (90 percent) and South Jersey (94 percent).

[ix] Zhang, K., & Batterman, S. (2013). Air pollution and health risks due to vehicle traffic. The Science of the total environment, 450-451, 307–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.01.074

[x] Center for Advanced Infrastructure and Transportation (CAIT) Rutgers University. (2020). Economic Impact Study of NJ Transit’s Five-Year Capital Plan. Population Health, Page 17. https://njtplans.com/downloads/capital-plan/Final%20Report_Economic%20Impact%20Study%20of%20NJ%20TRANSIT’s%205-year%20Capital%20Plan%206-5-20.pdf

[xi] Center for Advanced Infrastructure and Transportation (CAIT) Rutgers University. (2020). Economic Impact Study of NJ Transit’s Five-Year Capital Plan. Population Health, Page 17. https://njtplans.com/downloads/capital-plan/Final%20Report_Economic%20Impact%20Study%20of%20NJ%20TRANSIT’s%205-year%20Capital%20Plan%206-5-20.pdf

[xii] NJ Department of Environmental Protection. (2019). 2018 Statewide Greenhouse Gas Emissions Inventory. Page 4. https://www.nj.gov/dep/aqes/pdf/GHG%20Inventory%20Update%20Report%202018_Final.pdf

[xiii] U.S. Department of Transportation. Zero Emission Buses. Sierra Club https://www.transportation.gov/sites/dot.gov/files/images/Zero%20Emission%20Buses.pdf; U.S. Department of Transportation. (2015). Cleaner Air. https://www.transportation.gov/mission/health/cleaner-air

[xiv] Cooper, Erin, Arioli, Magdala, Carrigan, Aileen, & Jain, Umang. (2012, October). Exhaust Emissions of Transit Buses: Sustainable Urban Transportation Fuels and Vehicles. World Resources Institute. Page 2. https://wrirosscities.org/sites/default/files/Exhaust-Emissions-Transit-Buses-EMBARQ.pdf

[xv] NJ Transit. (2020a, June). Capital Plan Project Sheets, Appendix B: Bus Fleet. https://njtplans.com/downloads/capital-project-sheets/separated/NJ_Transit_Bus_Fleet.pdf

[xvi] American Lung Association. (2020, April 20). Particle Pollution. https://www.lung.org/clean-air/outdoors/what-makes-air-unhealthy/particle-pollution

[xvii] American Lung Association. (2020, April 21). Nearly Half of U.S. Breathing Unhealthy Air; Record-breaking Air Pollution in Nine Western Cities. Press Release. https://www.lung.org/media/press-releases/state-of-the-air-2020

[xviii] National Institutes of Health (NIH), (2018, January 23). Air pollution linked to risk of premature death. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/nih-research-matters/air-pollution-linked-risk-premature-death

[xix] PM2.5 refers to particulate matter less than 2.5μm in diameter.

Fabio Caiazzo, Akshay Ashok, Ian A. Waitz, Steve H.L. Yim, Steven R.H. Barrett. (2013). Air pollution and early deaths in the United States. Part I: Quantifying the impact of major sectors in 2005, Atmospheric Environment, Volume 79, 2013, Pages 198-208, ISSN 1352-2310. Table 5. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1352231013004548

[xx] Air pollution linked with higher COVID-19 death rates. (2020, May 5). News. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/hsph-in-the-news/air-pollution-linked-with-higher-covid-19-death-rates/

[xxi] What Do Coronavirus Racial Disparities Look Like State By State? (2020, May 30). National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/05/30/865413079/what-do-coronavirus-racial-disparities-look-like-state-by-state

[xxii] Disparities in the Impact of Air Pollution. (2020, April 20). American Lung Association. https://www.lung.org/clean-air/outdoors/who-is-at-risk/disparities

[xxiii] Union of Concerned Scientists. (2019). Inequitable Exposure to Air Pollution from Vehicles in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic. https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/inequitable-exposure-air-pollution-vehicles

[xxiv] Commonwealth of Massachusetts. (2017). Environmental Justice Policy of the Executive and Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs. Page 1. https://www.mass.gov/doc/open-space-and-recreation-plan-workbook/download

[xxv] The Century Foundation. (2020). Environmental Racism Has Left Black Communities Especially Vulnerable to COVID-19. https://tcf.org/content/commentary/environmental-racism-left-black-communities-especially-vulnerable-covid-19/?agreed=1

[xxvi] U.S. PIRG Education Fund, Environment America Research and Policy Center, and Frontier Group. (2019). Electric Buses in America: Lessons from Cities Pioneering Clean Transportation. Page 9. https://uspirg.org/sites/pirg/files/reports/ElectricBusesInAmerica/US_Electric_bus_scrn.pdf

[xxvii] Antti Lajunen, Timothy Lipman. (2016). Lifecycle cost assessment and carbon dioxide emissions of diesel, natural gas, hybrid electric, fuel cell hybrid and electric transit buses. Volume 106, 2016, Pages 329-342, ISSN 0360-5442, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2016.03.075.

[xxviii] Strauss, Rebecca. (2019). “Electric Buses and Clean Energy Financing: How Transit Authorities Can Leverage State and Federal Funds to Buy More Zero-Emission Buses” Georgetown Environmental Law Review. Volume 32. Issue 1. Fall 2019. Page 148. https://www.law.georgetown.edu/environmental-law-review/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2020/01/GT-GELR190049.pdf

[xxix] U.S. PIRG Education Fund, Environment America Research and Policy Center, and Frontier Group. (2019). Electric Buses in America: Lessons from Cities Pioneering Clean Transportation. Page 10. https://uspirg.org/sites/pirg/files/reports/ElectricBusesInAmerica/US_Electric_bus_scrn.pdf

[xxx] N.J.S.A. 48:25-3. https://lis.njleg.state.nj.us/nxt/gateway.dll?f=templates&fn=default.htm&vid=Publish:10.1048/Enu

[xxxi] NJ Transit. (2020). NJ Plans. https://njtplans.com/

[xxxii] New Jersey Transit, personal communication, August 2020.

[xxxiii] NJ Transit. (2020a, June). Capital Plan Project Sheets, Appendix B: Bus Fleet. Page 2. https://njtplans.com/downloads/capital-project-sheets/separated/NJ_Transit_Bus_Fleet.pdf

[xxxiv] NJ Transit. (2020a, June). Capital Plan Project Sheets, Appendix B: Bus Fleet. Page 5. https://njtplans.com/downloads/capital-project-sheets/separated/NJ_Transit_Bus_Fleet.pdf

[xxxv] NJ Transit. (2020, June). Unrestrained Financial Summary. Appendix A. Table 2. Page 5. https://njtplans.com/downloads/capital-plan/NJ_Transit_Capital_Plan_Financial_Summary_(Unconstrained).pdf

[xxxvi] NJ Transit. (2020, June). Capital Plan Project Sheets, Appendix B: Bus Garages. Page 2. https://njtplans.com/downloads/capital-project-sheets/separated/NJ_Transit_Bus_Garages.pdf

[xxxvii] NJ Transit. (2020c, June). Capital Plan Financial Summary (Unconstrained). Page 2. https://njtplans.com/downloads/capital-plan/NJ_Transit_Capital_Plan_Financial_Summary_(Unconstrained).pdf

[xxxviii] NJ Transit. (2020, June). Capital Plan Financial Summary (Unconstrained). Appendix A https://njtplans.com/downloads/capital-plan/NJ_Transit_Capital_Plan_Financial_Summary_(Unconstrained).pdf

[xxxix] NJ Transit. (2020, June). Capital Plan Project Sheets, Appendix B: Bus Garages. https://njtplans.com/downloads/capital-project-sheets/separated/NJ_Transit_Bus_Garages.pdf

[xl] NJ Transit. (2020, June). Capital Plan Project Sheets, Appendix B: Bus Garages. https://njtplans.com/downloads/capital-project-sheets/separated/NJ_Transit_Bus_Garages.pdf; NJ Transit. (2020c, June). NJT Capital Plan Unconstrained Financial Summary. https://njtplans.com/downloads/capital-plan/NJ_Transit_Capital_Plan_Financial_Summary_(Unconstrained).pdf

[xli] NJ Transit. (2020a, June). Capital Plan Project Sheets, Appendix B: Bus Fleet. https://njtplans.com/downloads/capital-project-sheets/separated/NJ_Transit_Bus_Fleet.pdf

[xlii] Politico Pro New Jersey. (2020, October 22). “NJ Transit board approves $2.6B budget with no fare increase.” https://subscriber.politicopro.com/states/new-jersey/story/2020/10/22/nj-transit-board-approves-26b-budget-with-no-fare-increase-1329547

[xliii] Johnson, T. (2020, June 19). NJ Transit Misses the Mark by Committing Just $15M to Electric Buses Through 2026, Critics Say. NJ Spotlight News. https://www.njspotlight.com/2020/06/nj-transit-misses-the-mark-by-committing-just-15m-to-electric-buses-through-2026-critics-say/

[xliv] NJ Transit. (2020c, June). NJT Capital Plan Unconstrained Financial Summary. Page 6. Table 2. https://njtplans.com/downloads/capital-plan/NJ_Transit_Capital_Plan_Financial_Summary_(Unconstrained).pdf

[xlv] NJ Transit. (2020c, June). NJT Capital Plan Unconstrained Financial Summary. https://njtplans.com/downloads/capital-plan/NJ_Transit_Capital_Plan_Financial_Summary_(Unconstrained).pdf

[xlvi] Government and External Affairs Department, New Jersey Transit, personal communication, August 2020.

[xlvii] NJ Transit and Rocky Mountain Institute. (January, 2020.) Bus Electrification Workshop. Slide 30.

[xlviii]Proterra. (2017). Current State of Public Transit Funding Options for Electric Vehicles and Charging Systems. American Public Transportation Association. https://www.apta.com/wp-content/uploads/Resources/mc/sustainability/previous/2017sustainability/presentations/Presentations/Current%20State%20of%20Public%20Transit%20Funding%20Options%20for%20Electric%20Vehicles%20and%20Charging%20Systems%20-%20Alan%20Westenskow.pdf

[xlix]Dickens, M. (2020, July 31). Public Transportation Vehicle Database [Dataset]. American Public Transportation Association. https://www.apta.com/research-technical-resources/transit-statistics/vehicle-database/

[l] Quarles, Neil, Kara Kockelman, and Moataz Mohamed. (2020) “Costs and Benefits of Electrifying and Automating Bus Transit Fleets,” Sustainability.https://doi.org/10.3390/su12103977; Lajunen, A., & Lipman, T. (2016). Lifecycle cost assessment and carbon dioxide emissions of diesel, natural gas, hybrid electric, fuel cell hybrid and electric transit buses. Energy, 106, 329–342.http://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2016.03.075

[li] L. Eudy, R. Prohaska, K. Kelly, and M. Post, “Foothill Battery Electric Bus Demonstration Results,” NREL/TP-5400-65274, National Renewable Energy Laboratory, January 2016). https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy17osti/67698.pdf

[lii] LA Metro. (2017). Contract 2016-0988 – Metro Board. https://boardagendas.metro.net/board-report/2016-0988/; LA Metro. (2017b). Contract 2017-0304 – Metro Board. https://boardagendas.metro.net/board-report/2017-0304/

[liii] The Guardian. (2021, Feb.) Electric busmaker Arrival schedules first UK road trial. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2021/feb/21/electric-busmaker-arrival-schedules-first-uk-road-trial

[liv] Quarles, Neil, Kara Kockelman, and Moataz Mohamed. (2020.) “Costs and Benefits of Electrifying and Automating Bus Transit Fleets.” Page 6. Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12103977; National Renewable Energy Laboratory, U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy. (2020.) Financial Analysis of Battery Electric Transit Buses. Technical Report. Page 8. https://afdc.energy.gov/files/u/publication/financial_analysis_be_transit_buses.pdf

[lv] Bloomberg New Energy Finance. (2018, March). Electric Buses in Cities: Driving Towards Cleaner Air and Lower CO2. Page 21. https://data.bloomberglp.com/professional/sites/24/2018/05/Electric-Buses-in-Cities-Report-BNEF-C40-Citi.pdf

[lvi] Bloomberg New Energy Finance. (2018, March). Electric Buses in Cities: Driving Towards Cleaner Air and Lower CO2. Page 22. https://data.bloomberglp.com/professional/sites/24/2018/05/Electric-Buses-in-Cities-Report-BNEF-C40-Citi.pdf

[lvii] Green Tech Media. (2019.) Proterra Rolls Out $200 Million Electric Bus Battery Leasing Program With Mitsui: Electric buses require more upfront investment than their diesel counterparts. Or at least they used to. https://www.greentechmedia.com/articles/read/proterra-rolls-out-bus-battery-leasing-program-with-mitsui

[lviii] This calculation is derived by taking the cost of an electric bus and subtracting it by the cost of batteries ($700,000-$196,000=$504,000).

[lix] Government and External Affairs Department, New Jersey Transit, personal communication, August 2020.

[lx] Maloney, P. (2019, October 17). Electric buses for mass transit seen as cost effective. American Public Power Association. https://www.publicpower.org/periodical/article/electric-buses-mass-transit-seen-cost-effective

[lxi] California Environmental Protection Agency. Air Resources Board. (2015). Technology Assessment: Medium-and Heavy-Duty Battery Electric Truck and Buses. Page V-9. https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/sites/default/files/classic//msprog/tech/techreport/bev_tech_report.pdf

[lxii]M.J. Bradley & Associates LLC. (2020). Battery Electric Bus and Facilities Analysis. Milwaukee County Transit System. https://www.mjbradley.com/sites/default/files/MTSElectricBusFinalReportFINAL15jan20_0.pdf; King County Metro Transit. (2017). Feasibility of Achieving a Carbon-Neutral or Zero Emission Fleet. King County Metro; Stantec Consulting Services Inc. (2020, October 13). https://kingcounty.gov/~/media/elected/executive/constantine/news/documents/Zero_Emission_Fleet.pdf; and University of Massachusetts Amherst. (2017). Zero-Emission Transit Bus and Refueling Technologies and Deployment Status. Massachusetts Department of Transportation. These are a few studies that show how transit authorities are using a mixed electric bus charging infrastructure.

[lxiii] King County Metro Transit. (2017). Feasibility of Achieving a Carbon-Neutral or Zero Emission Fleet. King County Metro; Stantec Consulting Services Inc. (2020, October 13). https://kingcounty.gov/~/media/elected/executive/constantine/news/documents/Zero_Emission_Fleet.pdf

[lxiv] WSP. (2020, April). San Bernardino Countywide Zero-Emission Bus Study Master Plan. San Bernandino County Transportation Authority. Pg. 38. https://www.gosbcta.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/SBCTA-ZEB-Final-Master-Plan_04.24.20.pdf; Burns & McDonnell Engineering Company, Inc., ebusplan, & Greenlots, A Member of the Shell Group. (2019). In Depot Charging and Planning Study. Foothill Transit. http://foothilltransit.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Burns-McDonnell-In-Depot-Charging-and-Planning-Study.pdf

[lxv]Proterra Northeast Regional Division of Sales, personal communication, August 2020.

[lxvi] Government and External Affairs Department, New Jersey Transit, personal communication, August 2020.

[lxvii] Aber, Judith. (2016, May). Electric Bus Analysis for New York City Transit. Columbia University. http://www.columbia.edu/~ja3041/Electric%20Bus%20Analysis%20for%20NYC%20Transit%20by%20J%20Aber%20Columbia%20University%20-%20May%202016.pdf

[lxviii] Chicago Transit Authority. (2019). Electric Buses. https://www.transitchicago.com/electricbus/#Benefits; Aber, Judith. (2016, May). Electric Bus Analysis for New York City Transit. Columbia University. http://www.columbia.edu/~ja3041/Electric%20Bus%20Analysis%20for%20NYC%20Transit%20by%20J%20Aber%20Columbia%20University%20-%20May%202016.pdf

[lxix] Sierra Club. (2020.) A Vision for Climate Leadership in Washington, DC: Seizing the Economic, Climate, and Public Health Benefits of Electrifying WMATA’s Transit Bus Fleet Page 12. https://www.sierraclub.org/sites/www.sierraclub.org/files/blog/WMATAReport_Final.pdf

[lxx] Environmental Defense Fund. (2020.) The true cost of carbon pollution. https://www.edf.org/true-cost-carbon-pollution; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Economics of Climate Change. https://www.epa.gov/environmental-economics/economics-climate-change

[lxxi] Aber, Judith. (2016, May). Electric Bus Analysis for New York City Transit. Columbia University. Page 19. http://www.columbia.edu/~ja3041/Electric%20Bus%20Analysis%20for%20NYC%20Transit%20by%20J%20Aber%20Columbia%20University%20-%20May%202016.pdf

[lxxii] This calculation is derived by multiplying the fleet of 2,665 buses and the greenhouse gas savings of $3,000.

[lxxiii] Tri-State Transportation Campaign, BlueWaveNJ, Clean Water Action, Environment New Jersey, New Jersey Policy Perspective, & New Jersey Sierra Club. (2020, April). Rail and Road Recovery. Tri-State Transportation Campaign. http://www.tstc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Rail-and-Road-To-Recovery-Final.pdf

[lxxiv] Advocacy Groups Urge NJ Turnpike Authority to Put the Brakes on $24B Capital Plan. (2020, April 28). NJ Spotlight. https://www.njspotlight.com/2020/04/advocacy-groups-urge-nj-turnpike-authority-to-put-the-brakes-on-24b-capital-plan/; CityLab, Bloomberg L.P., September 2018, “CityLab University: Induced Demand.” https://www.citylab.com/transportation/2018/09/citylab-university-induced-demand/569455/

[lxxv] NJ Spotlight News. (2020, March 3). Murphy’s Plan for NJ Transit: Where the Money’s Going to Come From. https://www.njspotlight.com/2020/03/murphys-plan-for-nj-transit-where-the-moneys-going-to-come-from/

[lxxvi] New Jersey’s Clean Energy Program. (2020). New Jersey’s Clean Energy Program. https://njcleanenergy.com/

[lxxvii] New Jersey Turnpike Authority. March 18, 2020 Public Hearings on 2020 Long-Range Capital Plan and Necessary Toll Adjustment on New Jersey Turnpike and Garden State Parkway. Pages 6-8. https://www.njta.com/media/5311/hearing-report-and-recommendation.pdf

[lxxviii] Politico New Jersey. (2020, September). NJ Transit budget may be sign board not functioning as reform law intended. https://www.politico.com/states/new-jersey/story/2020/09/18/nj-transit-budget-a-sign-board-not-functioning-as-reform-law-intended-1317170

[lxxix] Politico. (2020, September 30). Murphy signs a $32.7B budget that ‘will be there for the people of New Jersey.’ https://www.politico.com/news/2020/09/30/phil-murphy-budget-new-jersey-424274

[lxxx] Office of Legislative Services. (2020.) Legislative Fiscal Estimate. S2949. https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2020/Bills/S3000/2949_E1.PDF

[lxxxi] Sheila Reynerston, New Jersey Policy Perspective. (2017.) Fairly and Adequately Taxing Inherited Wealth Will Fight Inequality & Provide Essential Resources for All New Jerseyans. https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/fairly-and-adequately-taxing-inherited-wealth-will-fight-inequality-provide-essential-resources-for-all-new-jerseyans/

[lxxxii] Transportation and Climate Initiative. (2021.) Memorandum of Understanding. https://www.transportationandclimate.org/sites/default/files/TCI%20MOU%2012.2020.pdf

[lxxxiii] Transportation and Climate Initiative. (2021.) Memorandum of Understanding. https://www.transportationandclimate.org/sites/default/files/TCI%20MOU%2012.2020.pdf

[lxxxiv] Union of Concerned Scientists. (2019, June). Inequitable Exposure to Air Pollution from Vehicles in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic. https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/inequitable-exposure-air-pollution-vehicles?_ga=2.165707262.1575461946.1597037520-1621630665.1597037520

[lxxxv] Transportation and Climate Initiative Program. (2021, March 1). Summary of the Draft Model Rule. https://www.transportationandclimate.org/sites/default/files/Summary-of-TCI-P-Draft-Model-Rule-March-2021.pdf

[lxxxvi] Department of Environmental Protection. Frequently Asked Questions About the Federal Volkswagen Settlement and New Jersey. https://www.state.nj.us/dep/vw/faq.html

[lxxxvii] Department of Environmental Protection. Frequently Asked Questions About the Federal Volkswagen Settlement and New Jersey. Overview of Distribution of Mitigation Funds. https://www.state.nj.us/dep/vw/project.html

[lxxxviii] Department of Environmental Protection. Frequently Asked Questions About the Federal Volkswagen Settlement and New Jersey. https://www.state.nj.us/dep/vw/faq.html

[lxxxix] Federal Transit Administration. (2020). Fiscal Year 2020 Low or No-Emission (Low-No) Bus Program Projects. https://www.transit.dot.gov/funding/grants/fiscal-year-2020-low-or-no-emission-low-no-bus-program-projects

[xc] Federal Transit Authority. (2020) Grants for Buses and Bus Facilities Program. https://www.transit.dot.gov/bus-program

[xci] Larry Higgs, NJ Advance Media for NJ.com. (2020a, August 7). NJ Transit gets $15M federal grant to pave the way for electric buses. Nj. https://www.nj.com/news/2020/08/nj-transit-gets-15m-federal-grant-to-pave-the-way-for-electric-buses.html

[xcii] U.S. Department of Transportation. (2020.) About BUILD Programs. https://www.transportation.gov/BUILDgrants/about

[xciii] U.S. Department of Energy. (2016.) State Energy Resilience Framework. Prepared by Global Security Sciences Division, Argonne National Laboratory. Page 2. https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2017/01/f34/State%20Energy%20Resilience%20Framework.pdf

[xciv] Bailey, L. (2020, October). Planning for a Climate Resilient Electric Bus Fleet. Tri-State Transportation Campaign. Page 10. http://www.tstc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/09-29-2020_Resiliency-Report.pdf

[xcv] UC San Diego, Jacobs School of Engineering. (2018, April 5). A power player for San Diego. Press release. https://jacobsschool.ucsd.edu/news/release/2519

[xcvi] Maldonado, S. (2021, January 26). Environmentalists: Proposed PSE&G electric vehicle settlement won’t advance state’s goals. Politico PRO. https://www.politico.com/states/new-jersey/story/2021/01/26/environmentalists-proposed-pse-g-electric-vehicle-settlement-wont-advance-states-goals-1360277

[xcvii] Dutzik, Tony, & Friedman, Jamie. (2020). Renewables on the Rise. Environment America Research & Policy Center and Frontier Group. https://environmentamerica.org/feature/ame/renewables-rise-2020

[xcviii] New York Times. (2021, January 21). ‘Notorious’ Port Authority Bus Terminal May Get a $10 Billion Overhaul. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/21/nyregion/port-authority-bus-terminal.html

[xcix] Utah Department of Environmental Quality. (2021). Monitoring Matters: How Air-Quality Monitoring Helps Utah’s Air. https://deq.utah.gov/air-quality/air-quality-monitoring-utah

[c] Josh Axelrod, NJ Advance Media for NJ.com & Larry Higgs, NJ Advance Media for NJ.com. (2020, December 31). A bus driver, a mechanic, a bridge operator. These 15 NJ Transit employees died from COVID-19. Nj. https://www.nj.com/community-news/2020/12/a-bus-driver-a-mechanic-a-bridge-operator-these-15-nj-transit-employees-died-from-covid-19.html

[ci] Center for Transportation and the Environment. (2019.) Zero Emission Bus Roadmap. In partnership with: SINGH + Associates, Inc. Page 66. https://www.cyride.com/Home/ShowDocument?id=9880