For the thousands of people incarcerated in New Jersey’s prisons and jails, a phone call to loved ones can make a significant difference during challenging and isolating times. Research consistently shows that communication between people behind bars and their support systems helps to improve their mental health in the short term and strengthen the relationships needed for a successful reentry in the long term.[i]

Yet, despite the importance of these connections with the outside world, communication is increasingly out of reach for individuals incarcerated in New Jersey due to the exorbitant fees charged by private, for-profit telecommunication companies that have monopoly contracts with corrections agencies.[ii] Because incarcerated individuals and their families bear these costs, fees for prison communication disproportionately harm women, people of color, and families with low incomes, exacerbating racial and economic inequities within the criminal legal system and throughout the state.[iii]

By moving away from this profit-driven model and providing accessible communication across the state’s prisons and county jails, New Jersey can keep families connected, allow people who are incarcerated to better plan for their releases, and finally put a stop to the predatory practices that cost families across the state $15 million every year, based on analysis by Worth Rises.[iv] While this is an incredible burden for families, the expense for the state is a small fraction — 1.4 percent — of the nearly $1.1 billion correctional facilities budget.[v]

How We Got Here: The Rise of Private Prison Communications

Until the 1980s, prisons in the United States managed access to phone calls through AT&T, with many facilities providing collect calls at prices comparable to the cost of a collect call on the outside.[vi] With the rapid growth of incarceration fueled by the War on Drugs, the federal break-up of the AT&T monopoly, and the subsequent “prison boom” of the 1980s, private telecommunication companies emerged, and their business models capitalized on the growing number of prisons and jails across the United States, cornering the market, commissions to prison and jail administrators, and making calls more expensive.[vii]

New Jersey is one of many states that contracts with private telecom companies to provide communication services for its prisons, including phone calls, electronic messaging, and video calls. The state currently contracts with two companies: ViaPath, formerly Global Tel Link, and JPay, a subsidiary of Securus Technologies.[viii] Founded in 1989, ViaPath was one of the first companies to transform prison phone calls into a multimillion-dollar industry.[ix] JPay, founded in 2002 as a prison money-wiring service, has since emerged as one of the largest prison technology contractors in the country.[x]

ViaPath and JPay make up nearly 80 percent of the prison communication market share in the United States, and their monopoly contracts allow them to charge exorbitant fees and generate hundreds of millions of dollars in profit from incarcerated individuals and their families.[xi] The two companies have each faced their fair share of price-gouging complaints, with ViaPath, ordered to pay $67 million to settle a 2015 class-action lawsuit, and JPay ordered to pay $6 million in fines and restitution in 2021 for charging excessive and illegal fees.[xii]

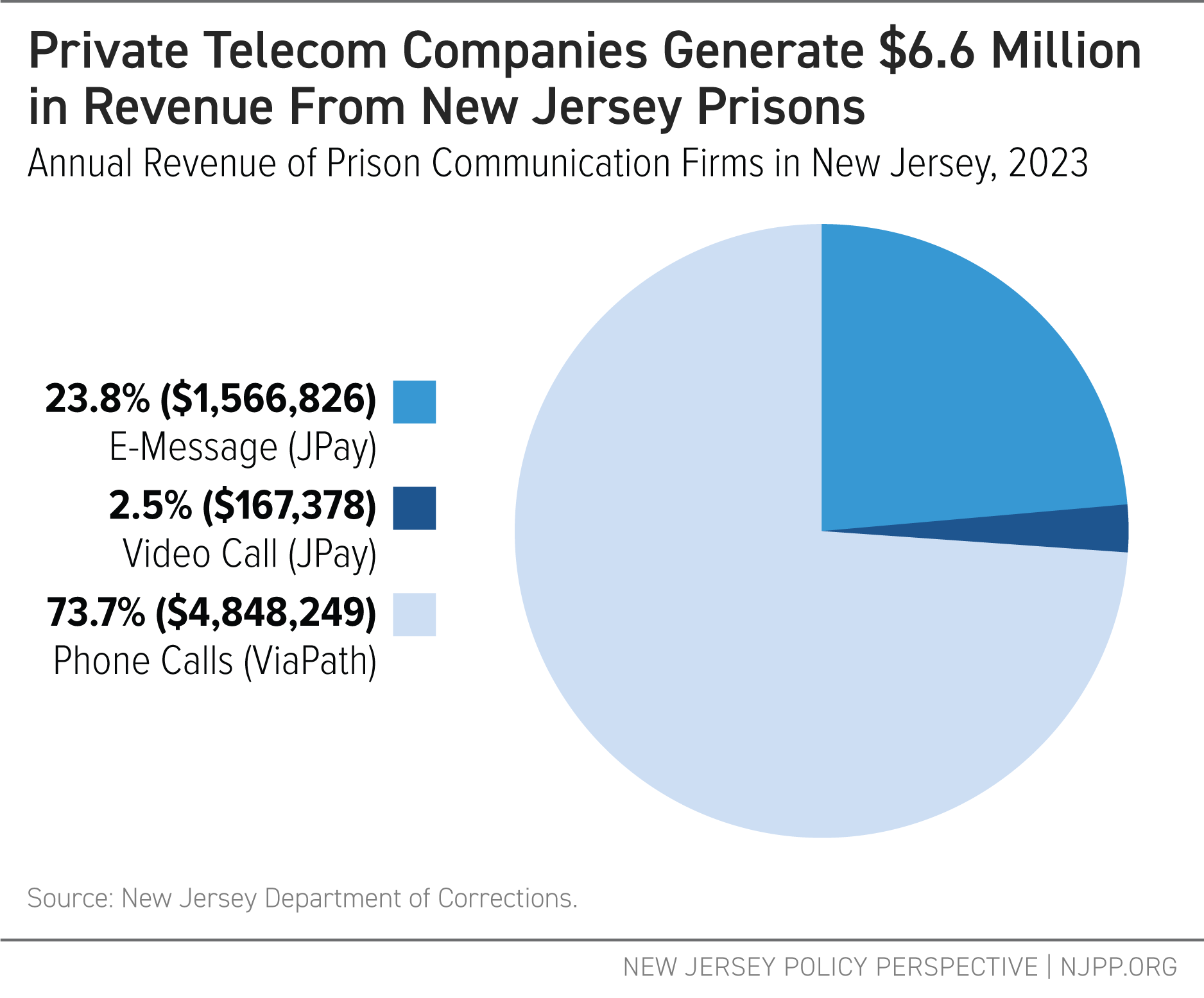

In 2023, ViaPath and JPay brought in a combined $6.6 million in revenue from their monopolies on phone calls, e-messages, and video calls in New Jersey’s state prisons.[xiii] Phone calls made up nearly three-quarters of prison communication revenue in New Jersey, with ViaPath bringing in more than $4.8 million from state prisons. Electronic messaging made up 24 percent of prison communication revenue, and video calls made up the remaining 2.5 percent. JPay brought in a combined $1.7 million from electronic messages and video calls.

How it Works: The High Cost of Private Prison Communications

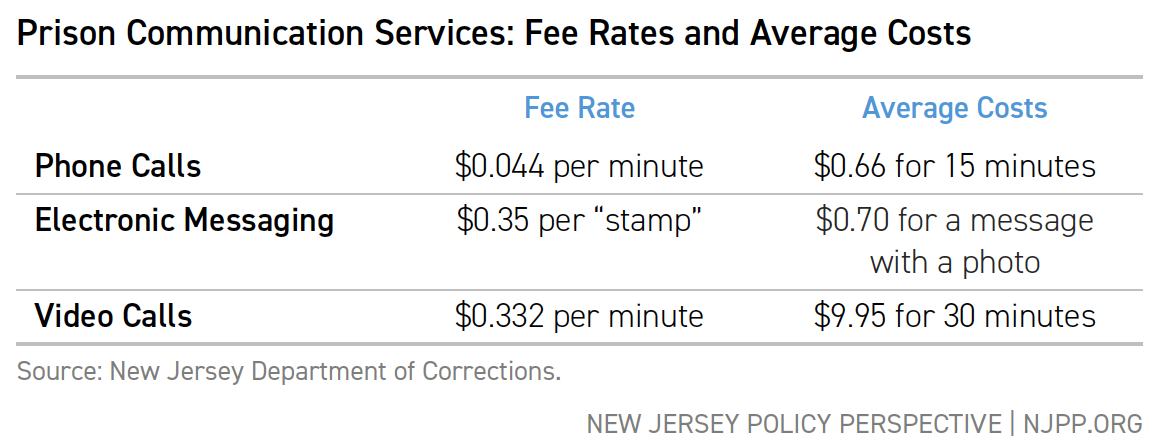

Phone calls are the primary communication channel in New Jersey’s prisons, with ViaPath charging fees of about $0.044 per minute at state facilities and even higher rates at some county jails.[xiv] High fees, combined with call limits of fifteen minutes, make it less likely that incarcerated individuals will stay in touch with their families, straining the relationships that are critical to their success when they are released.

According to a recent survey by the New Jersey Office of Corrections Ombudsperson, many people incarcerated in New Jersey do not feel they have enough time on the telephone to maintain relationships with their loved ones.[xv] Still, the majority indicated the phone as their preferred method of communication.[xvi]

Incarcerated individuals also rely on a basic form of electronic messaging offered by JPay, similar to email, but without direct internet access. Electronic messages are composed on low-tech tablets sold by JPay,[xvii] often for $50, and then connected to a kiosk that delivers the message. Sending messages requires the purchase of credits, known as “stamps,” that cost $0.35 each.[xviii] Each message requires one stamp, and additional stamps are needed for receiving a message with a photo attached or sending one that exceeds a single page in length.

Video calls offered by JPay operate on the same system of kiosks and tablets as electronic messages. At $9.95 for thirty minutes,[xix] they are extraordinarily expensive for incarcerated individuals and their families. It’s worth noting that not all correctional facilities in New Jersey currently provide access to video calls.

While this business model results in hundreds of millions of dollars in profits for companies like ViaPath and JPay, it has devastating consequences for incarcerated people and their families, with repercussions that reverberate into communities across New Jersey and the rest of the nation.

How Private Prison Communications Harm New Jersey Families

The cost of prison communications imposes a severe burden on incarcerated individuals and their families, who often shoulder the cost. Poverty and incarceration are inextricably linked in the United States, where the vast majority of people incarcerated are low-income, while incarceration itself results in greater poverty.[xx] For these individuals and families, any cost associated with communication can be an insurmountable challenge that perpetuates cycles of poverty and inequality.

Fees for phone calls, video calls, and electronic messages add up quickly, with incarcerated individuals and their families paying $15 million annually to stay connected. This includes $7.4 million spent across New Jersey’s state prisons and an additional $7.6 million across county jails.[xxi]

For incarcerated individuals, wages inside correctional facilities are far too low to afford the fees charged by ViaPath and JPay to stay in regular contact with their families and support systems, forcing their families to foot the bill. Incarcerated workers are exempt from New Jersey’s minimum wage law and work at a daily, not hourly, rate. They can earn anywhere from $1.60 to $7.50 a day, with most workers earning between $1.60 and $3.00, on average.[xxii]

For the large portion of people in prison who earn the lowest daily pay rate ($1.60), making a phone call home or sending an email costs them nearly half of their earnings for the day. For example, it would cost $1.36 to have a 15 minute phone call and receive one email with a photo attachment, nearly wiping out one’s daily earnings.[xxiii] In Fiscal Year 2022, the total wages paid to all incarcerated people in New Jersey was $9.2 million.[xxiv] Put another way, if people who are incarcerated relied solely on their wages to pay for communication, 72 percent of their total earnings would have gone toward calls and messages.

However, people in prison must pay for more than just communications, such as, basic hygiene items from commissary,[xxv] child support, and some medicines, and with such low wages, they are often unable to afford the communications they so desperately need. As a result, the vast majority of costs end up falling onto the shoulders of family members and other loved ones, who are disproportionately women of color.

Nationally, one in three families with an incarcerated loved one goes into debt due to the fees associated with trying to stay connected.[xxvi] Of family members responsible for incarceration-related costs, 83 percent were women, with women of color disproportionately affected given the racial disparities in the criminal legal system.[xxvii] New Jersey has the highest Black-white disparity in incarceration in the country, with 61 percent of incarcerated individuals identifying as Black and only 22 percent as white.[xxviii]

The for-profit prison communication system has far-reaching effects on the finances and overall well-being of families across the state. In a recent op-ed in The Star-Ledger, Malika McCall, a mother and business owner in Newark whose two sons were incarcerated in New Jersey, detailed the financial and emotional toll of not being able to afford to keep in touch with her children. Malika’s story is both heartbreaking and all too common for families with a loved one incarcerated in New Jersey.

From going into debt to not taking calls because of an inability to pay, the consequences of high fees extend beyond financial stress; they irreparably harm the bonds between parents and their children and take a significant emotional toll on families already struggling to get by.

Building Bridges and Connecting Families with Free Prison Communications

There is a growing movement of states and local governments recognizing the importance of connecting families and removing barriers to communication. In the last three years, five states and multiple jurisdictions, including New York City, have eliminated fees associated with prison communication, setting an example for New Jersey and other states to follow.[xxix] And just this summer, the Federal Communications Commission passed new rules that put caps on phone and video calling rates in prisons and jails and ban corporate kickbacks on these services to prison and jail administrators.[xxx]

At the core of accessible prison communications is family, human dignity, and a commitment to ensuring the successful return to community. When incarcerated people can regularly connect with their families, it fosters a sense of hope, encourages productive behavior, and enhances participation in rehabilitation programs.[xxxi] Moreover, facilitating open lines of communication between incarcerated individuals and their support networks stands out as one of the most effective strategies to bolster reentry outcomes and reduce recidivism rates.[xxxii] By eliminating communication fees, New Jersey can keep families connected and finally put a stop to the predatory practices that cost families across the state $15 million every year.

End Notes

[i] Wang, L. Research roundup: The positive impacts of family contact for incarcerated people and their families, Prison Policy Initiative. Decmber 21, 2021 https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2021/12/21/family_contact/

[ii] Worth Rises. The Prison Industry How It Started How It Works and How It Harms. December, 2020. Pg. 48-49. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/58e127cb1b10e31ed45b20f4/t/621682209bb0457a2d6d5cfa/1645642294912/The+Prison+Industry+How+It+Started+How+It+Works+and+How+It+Harms+December+2020.pdf

[iii] deVuono-powell, Saneta et al. Who Pays? The True Cost of Incarceration on Families. Ella Baker Center, September, 2015. Pg. 9 https://ellabakercenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Who-Pays-exec-summary.pdf

[iv] Based on fiscal analysis done by Worth Rises using current DOC and jail population data and 2023 usage data including taxes and deposit fees paid by families. This figure includes the costs associated with both prisons ($7.4 million) and county jails ($7.6 million). Methodology is on file with author.

[v] Governor’s Detailed Budget. FY2025. Pg. B-2. https://www.nj.gov/treasury/omb/publications/25budget/pdf/FY2025-Budget-Detail-Full.pdf

[vi] Worth Rises. The Prison Industry How It Started How It Works and How It Harms. December, 2020. Pg. 48. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/58e127cb1b10e31ed45b20f4/t/621682209bb0457a2d6d5cfa/1645642294912/The+Prison+Industry+How+It+Started+How+It+Works+and+How+It+Harms+December+2020.pdf

[vii] Worth Rises. The Prison Industry How It Started How It Works and How It Harms. December, 2020. Pg. 48. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/58e127cb1b10e31ed45b20f4/t/621682209bb0457a2d6d5cfa/1645642294912/The+Prison+Industry+How+It+Started+How+It+Works+and+How+It+Harms+December+2020.pdf

[viii] JPay was acquired by Securus in 2015 and has been referred to by both names by the press and other stakeholders.(https://theappeal.org/prison-tablets-ipads-jpay-securus-gtl/) New Jersey is currently looking to cut ties with JPay and have ViaPath take over all prison communications.(https://www.njspotlightnews.org/2024/04/nj-prison-ombudsperson-examines-phone-access-policies-urges-corrections-department-change-policies/)

[ix] Schwenk, K. Wall Street Is Finding New Ways to Milk the Prison System. Jacobin. February, 2024.https://jacobin.com/2024/02/prison-phone-calls-telecom-revenue

[x] Law, V. Captive Audience: How Companies Make Millions Charging Prisoners to Send An Email. Wired. August, 2018. https://www.wired.com/story/jpay-securus-prison-email-charging-millions/

[xi] Wagner, P. and Bertram, W. State of Phone Justice 2022, Prison Policy Initiative. December, 2022. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/phones/state_of_phone_justice_2022.html

[xii] Land, G. Prison Phone Co. to Pay $67M to Settle Claims It Looted ‘Inactive’ Accounts. Law.com. December, 2021. https://www.law.com/dailyreportonline/2021/12/06/prison-phone-co-to-pay-67m-to-settle-claims-it-looted-inactive-accounts/?slreturn=20240626133133 & Flitter, E .JPay, a prison contractor, was fined over fees it charged to former prisoners. New York Times. October, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/19/business/jpay-prison-card-fees.html

[xiii] Data NJPP received from NJ DOC. These figures are for state correctional facilities alone and do not include revenues from county jails.

[xiv] Data Worth Rises acquired while performing their fiscal analysis.The prices vary in county jails, but the average rate is $0.051 per minute, or $0.77 for a 15 minute phone call.

[xv] NJ Office of the Corrections Ombudsperson. Visits and Phone Calls, Special Report. April, 2024. Pg. 8. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/24539968-special-report-on-visits-and-phone-calls_corrections-ombudsperson

[xvi] NJ Office of the Corrections Ombudsperson. Visits and Phone Calls, Special Report. April, 2024. Pg. 6. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/24539968-special-report-on-visits-and-phone-calls_corrections-ombudsperson

[xvii] Law, V. Captive Audience: How Companies Make Millions Charging Prisoners to Send An Email. Wired. August, 2018. https://www.wired.com/story/jpay-securus-prison-email-charging-millions/

[xviii] NJ Office of the Corrections Ombudsperson. Visits and Phone Calls, Special Report. April, 2024. Pg. 8. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/24539968-special-report-on-visits-and-phone-calls_corrections-ombudsperson

[xix] NJ Office of the Corrections Ombudsperson. Visits and Phone Calls, Special Report. April, 2024. Pg. 8. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/24539968-special-report-on-visits-and-phone-calls_corrections-ombudsperson

[xx] deVuono-powell, Saneta et al. Who Pays? The True Cost of Incarceration on Families. Ella Baker Center, September, 2015. Pg. 9 https://ellabakercenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Who-Pays-exec-summary.pdf

Note: In New Jersey, data from the Office of the Public Defender suggests that 90% of all criminal defendants are indigent, or without resources. https://pub.njleg.gov/publications/reports/CSDC%20Third%20Report.pdf

[xxi] Based on fiscal analysis done by Worth Rises using current DOC and jail population data and 2023 usage data including taxes and deposit fees paid by families.

[xxii] DiFilippo, D. Inflation hits inmates’ wallets, even as their wages have flatlined. NJ Monitor. September, 2022. https://newjerseymonitor.com/2022/09/28/inflation-hits-inmates-wallets-even-as-their-wages-have-flatlined/ & NJ DOC response to FY24 budget hearing questions. 2023. Pg. 20-21. https://pub.njleg.state.nj.us/publications/budget/governors-budget/2024/DOC_response_2024.pdf Note that the wages now range from 1.60 to 7.50 due to an increase in wages in April, May and June of 2024.

[xxiii] NJPP analysis of data obtained from Worth Rises and NJDOC

[xxiv] NJ DOC response to FY24 budget hearing questions. 2023. Pg. 21. https://pub.njleg.state.nj.us/publications/budget/governors-budget/2024/DOC_response_2024.pdf

[xxv] Detailed NJDOC commissary price list acquired by The Appeal. 2024. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/24444224-nj_doc_combined_commissary_lists

[xxvi] deVuono-powell, Saneta et al. Who Pays? The True Cost of Incarceration on Families. Ella Baker Center, September, 2015. Pg. 9 https://ellabakercenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Who-Pays-exec-summary.pdf

[xxvii] deVuono-powell, Saneta et al. Who Pays? The True Cost of Incarceration on Families. Ella Baker Center, September, 2015. Pg. 9 https://ellabakercenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Who-Pays-exec-summary.pdf

[xxviii] NJ Department of Corrections. Incarcerated Persons In New Jersey Correctional Institutions

On January 1, 2024, By Race/Ethnic Identification. January, 2024. https://www.nj.gov/corrections/pdf/offender_statistics/2024/By_Race-Ethnicity_2024.pdf

[xxix] Kaiser-Schatzlein, R. Is This the End of Prison Phone Fees? Mother Jones. October 2023. https://www.motherjones.com/criminal-justice/2023/08/conneticut-prison-phone-fees-securus/

[xxx] Bertram, W. FCC votes to slash prison and jail calling rates and ban corporate kickbacks. Prison Policy Initiative. July 2024. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2024/07/18/fcc-vote/

[xxxi] Wang, L. Research roundup: The positive impacts of family contact for incarcerated people and their families, Prison Policy Initiative. Decmber 21, 2021 https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2021/12/21/family_contact/ & Worth Rises. The Prison Industry How It Started How It Works and How It Harms. December, 2020. Pg. 52. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/58e127cb1b10e31ed45b20f4/t/621682209bb0457a2d6d5cfa/1645642294912/The+Prison+Industry+How+It+Started+How+It+Works+and+How+It+Harms+December+2020.pdf

[xxxii] Petersilia, Joan. When Prisoners Come Home: Parole and Prisoner Reentry. Oxford University Press, 2006, p 246.

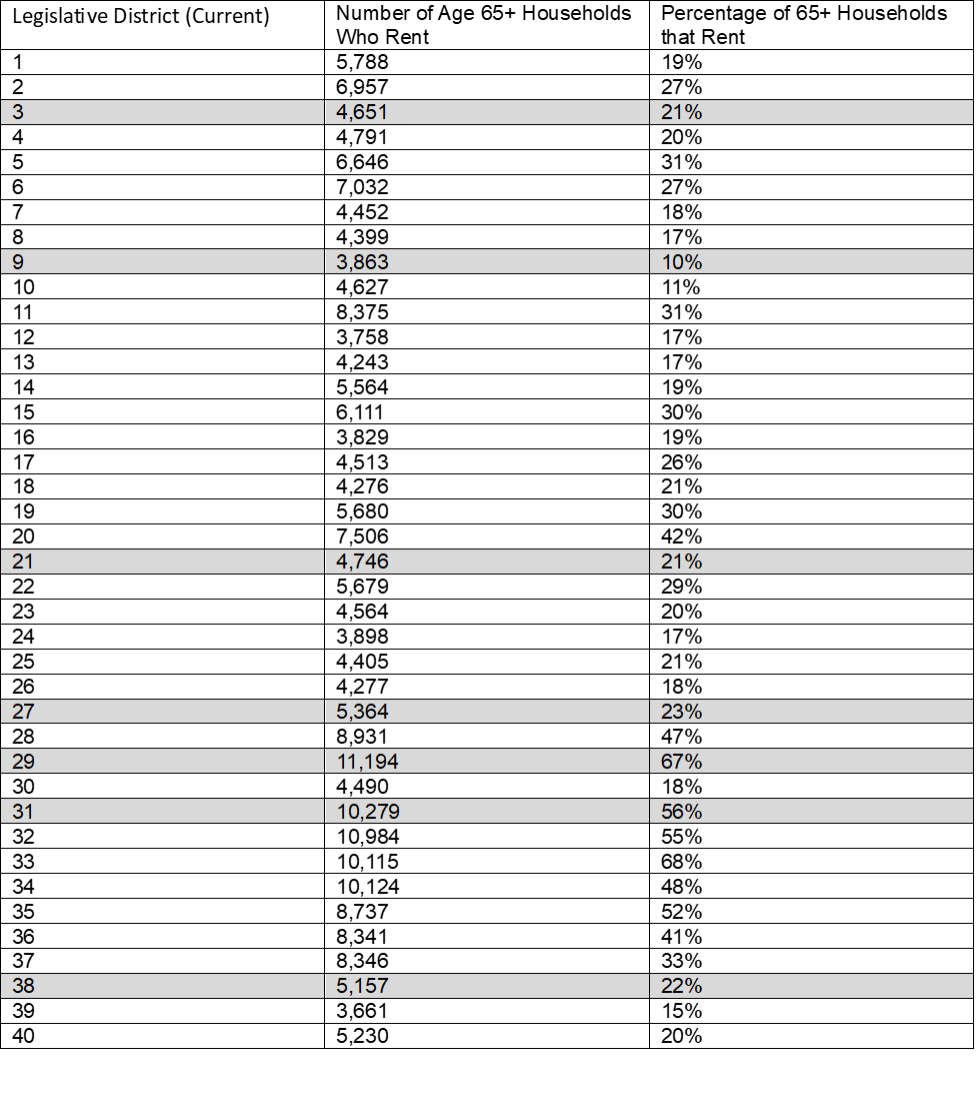

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2020 Demographic and Housing Characteristics Table H13

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2020 Demographic and Housing Characteristics Table H13