To read a PDF version of this report, click here.

Because of legislative changes made in 2013, New Jersey’s surge in corporate tax subsidies has risen to unprecedented levels, further cramping New Jersey’s ability to invest in schools, transportation and other areas known to be greater drivers of job creation.

This policy shift comes with an enormous financial reward to very few corporations and an enormous cost to Garden State taxpayers. But it doesn’t have to be this way. In fact, 10 key reforms – from forcing policymakers to actually pay for the tax breaks that happen on their watch to reducing the focus on retaining jobs that are already in New Jersey – could help rebalance the scales and ensure a more responsible approach to economic development in the Garden State.

An Unproven Strategy With Poor Results

Taxes play a minor part in business location decisions, and tax breaks – unlike investments in public assets like transportation or higher education – are not proven to grow a state’s economy.

It’s no mystery why that’s the case, considering that state and local taxes make up less than 5 percent of the cost of doing business.[1] In other words, while most large companies will gladly take a tax break, few will move to a location solely because of it. Other factors – like proximity to markets, a well-educated workforce and safe communities with high-quality schools and access to transportation – are far more important, according to surveys of executives from large corporations.[2]

Yet despite the fact that “economic activity is fairly unresponsive to changes in taxes,” as the Urban Institute notes, tax subsidies’ allure “can be overwhelming because they usually have a higher short-term political return than longer-term policies” and because of the fear of losing a major company to another state.[3] Researchers call this the “ribbon-cutting effect” – the unmistakable desire of political leaders to look like they are working hard to create jobs and grow the economy.

And most small businesses – particularly Main Street firms that form the bedrock of communities across the state – don’t benefit from subsidies at all. In fact, just 15 percent of small business owners have even accessed them, according to one recent survey. Not surprisingly, a third of respondents in that same survey said they have “little knowledge or experience” of or with these tax breaks, another 30 percent said these subsidies do “little for small businesses” and just 17 percent said they were “essential for job creation and economic growth.”[4]

In New Jersey, an increasing reliance on big-dollar tax breaks since 2010 has done little to significantly improve the state’s economy. On nearly every economic metric available, the state remains far behind neighboring states and the nation.

From 2014 to 2015, while an increasingly strong recovery helped American median household incomes grow by more than 5 percent, New Jersey’s household income barely grew at all, with anemic 0.3 percent growth that was the slowest in the nation.[5] When adjusted for inflation, New Jersey’s median household income in 2015 remained 6 percent lower than it was in 2007.[6]

From 2014 to 2015, while an increasingly strong recovery helped American median household incomes grow by more than 5 percent, New Jersey’s household income barely grew at all, with anemic 0.3 percent growth that was the slowest in the nation.[5] When adjusted for inflation, New Jersey’s median household income in 2015 remained 6 percent lower than it was in 2007.[6]

Taking a broader look, more than 7 years after the recession’s official end, New Jersey has just 24,900 more jobs it did before the recession began. As of March 2017, New Jersey had the eighth slowest job growth (0.6 percent) since December 2007. For comparison, the nation as a whole has grown jobs by 5.4 percent during that same time, while the Northeast region – even including New Jersey – has posted growth of 4.6 percent.[7]

These trends have held even as New Jersey’s job growth has experienced a slight uptick: the state’s job growth since January 2010 has been the 11th slowest in the nation, and its growth since the Economic Opportunity Act went into effect in December 2013 remains in the bottom third of the states (17th slowest).

But these ineffective tax breaks aren’t just failing to grow the economy and a robust middle class in New Jersey. They are also making it harder to maintain and improve the state’s economy moving forward, by creating a damaging cycle of disinvestment that puts the state’s future at risk. Each dollar of subsidy New Jersey approves is a dollar it stands to lose in the coming years, making it even harder to restore key investments in the very things that corporations put at the top of the list when deciding where to locate their businesses.

Subsidy Programs Have Become Unaffordable

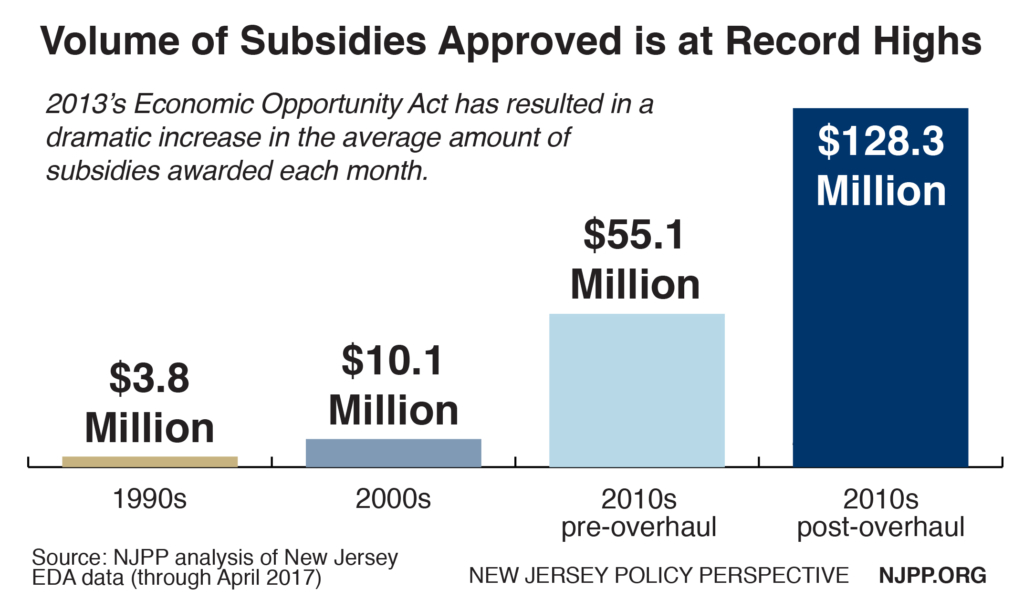

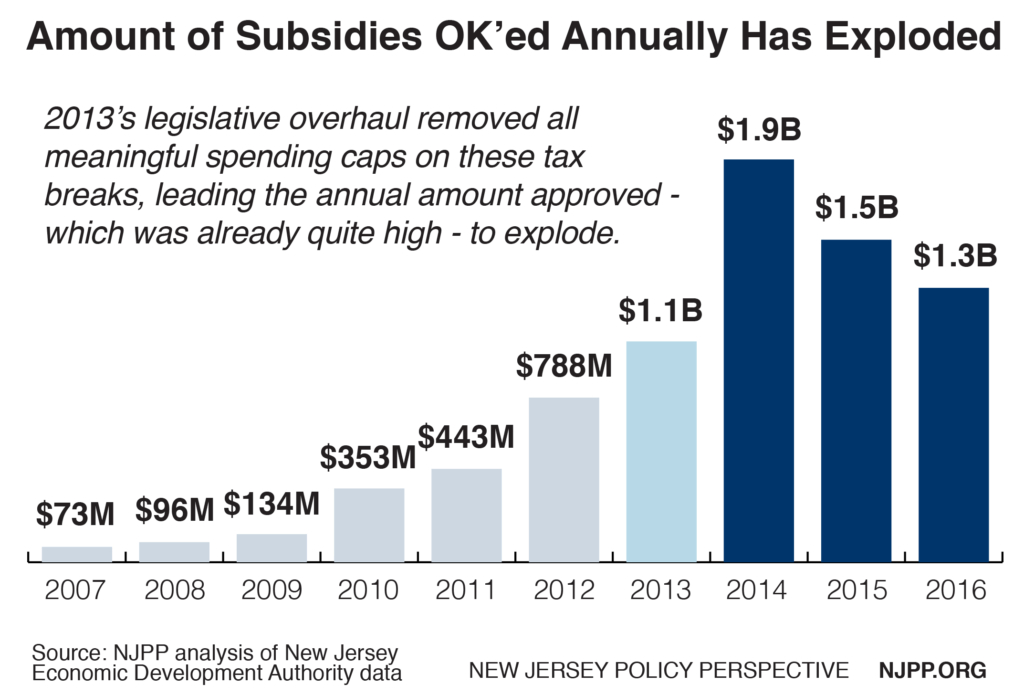

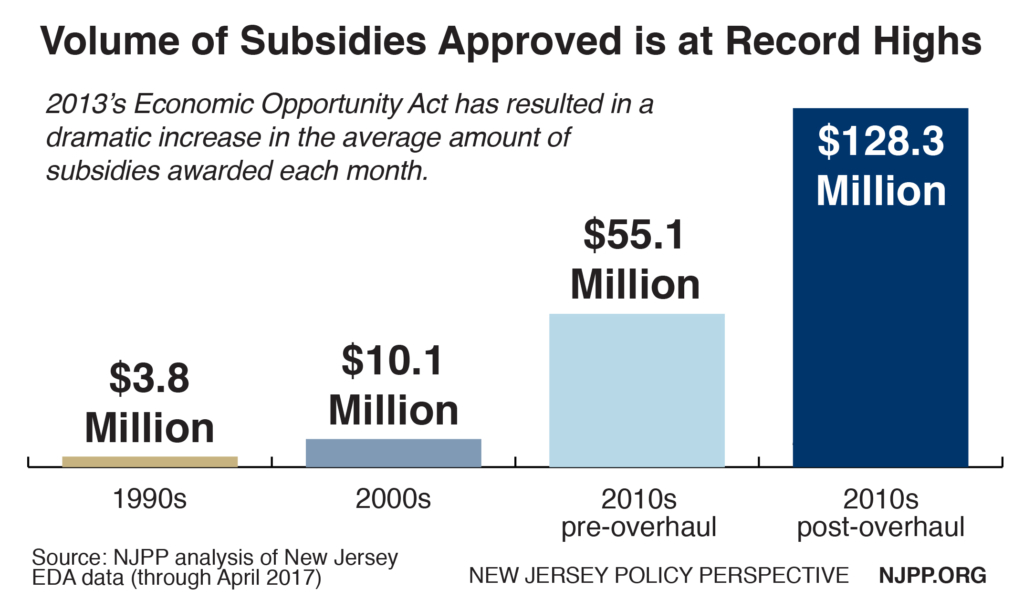

It’s been over three years since New Jersey began approving subsidies under the “Economic Opportunity Act of 2013,” which dramatically expanded these tax break offerings, made them more generous to corporations and removed key financial safeguards, including most ceilings on how much the state can spend on subsidies.

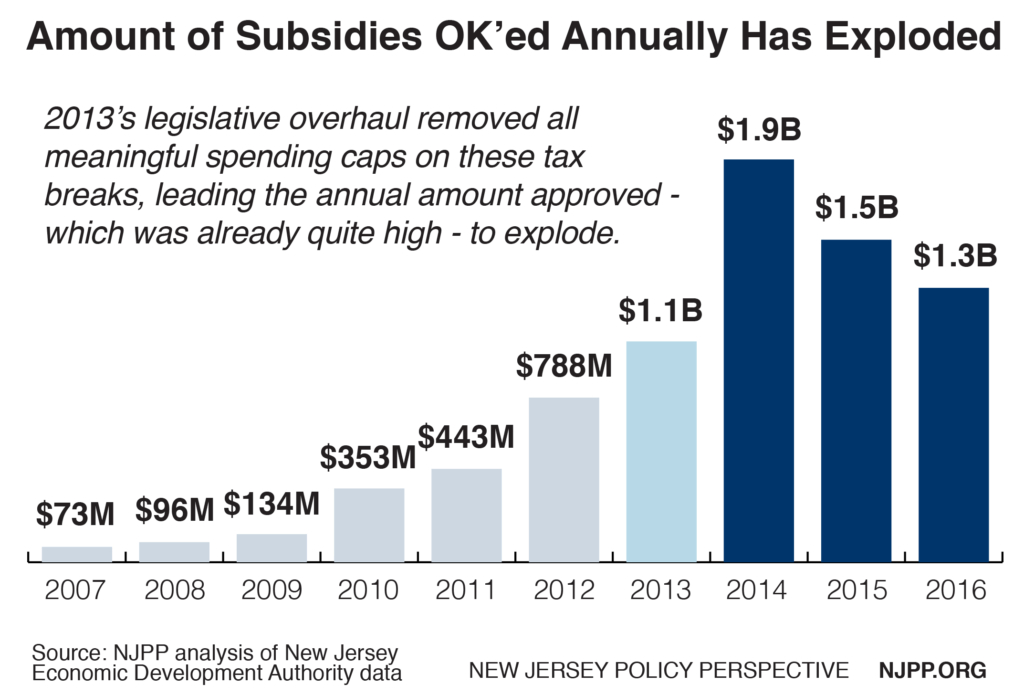

In the 41 months since the state Economic Development Authority (EDA) – which manages these programs – began approving subsidies under the new law, the volume awarded by New Jersey has skyrocketed, exacerbating an already surging reliance on these tax breaks since 2010.

Since December 2013 New Jersey has approved $5.3 billion in tax subsidies, bringing the total since January 2010 to $7.9 billion.[8] That’s more than six times as much as were awarded in the entire previous decade, when the state approved $1.2 billion.

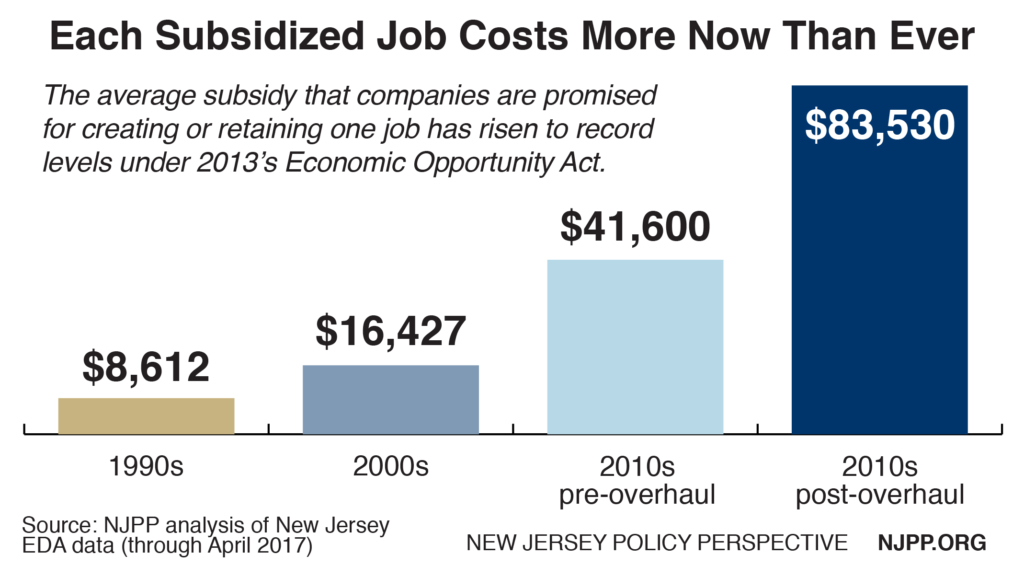

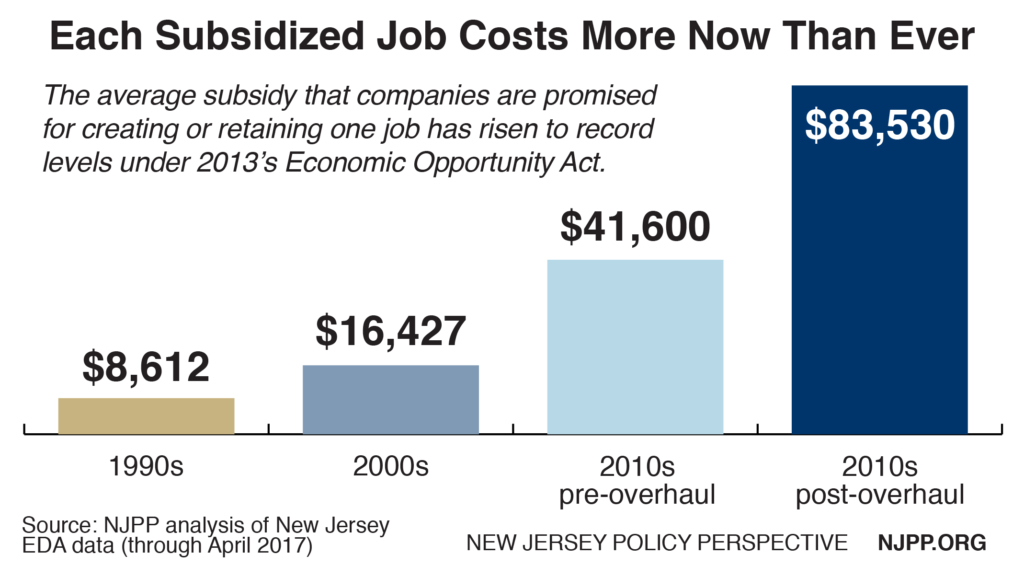

And it’s not just the overall amount of subsidies that has exploded. These tax breaks have become far more lucrative to the corporations receiving them – and far more expensive to taxpayers – with the state giving up more and more tax dollars for each job a subsidy recipient creates or retains.

Post-overhaul, the cost per job is over $83,000, far higher than the $41,600 earlier this decade and more than five times higher than the cost of $16,427 in the 2000s.

And what’s worse, nearly half of these jobs – 45 percent in the “Economic Opportunity Act” era – were already here in New Jersey. This is because the tax breaks focus on retaining jobs that corporations threaten – often idly – to move to other states. The result is that New Jersey taxpayers are often footing the bill for profitable corporations to build new headquarters down the road from their current locations.

This was not always the case in New Jersey. In the 2000s, just 25 percent of these jobs were “retained” jobs; and in the 1996-1999 era, none were.

When one strips out these “retained jobs,” and focuses solely on the jobs that are new to New Jersey, the average taxpayer cost per job skyrockets to $152,119 since December 2013 – about double the cost earlier this decade ($77,054) and about seven times higher than the cost of $21,878 in the 2000s.

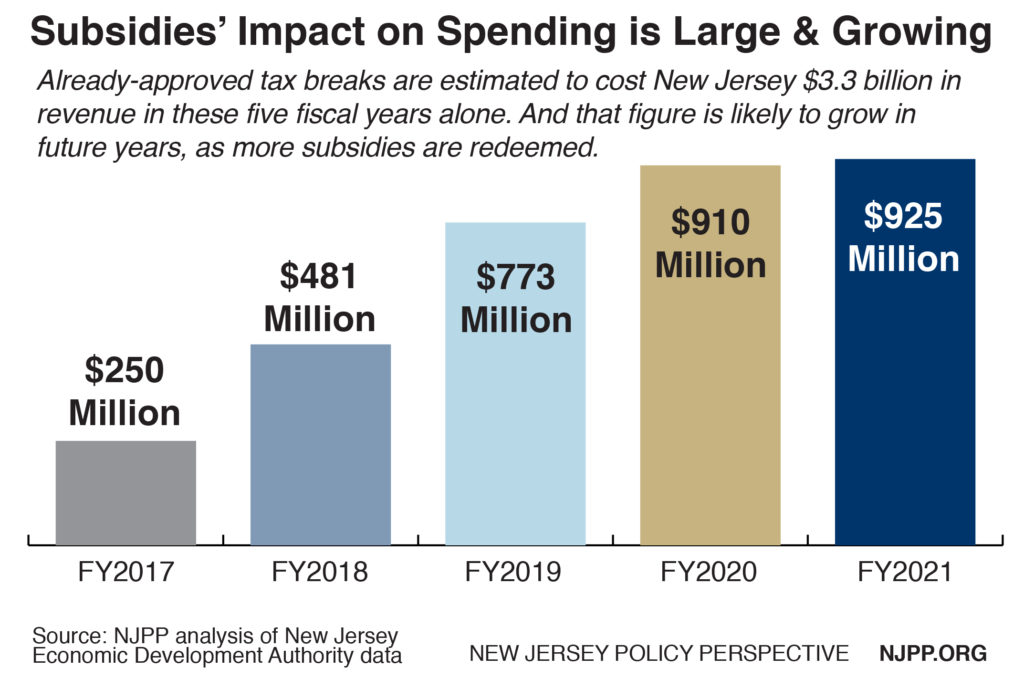

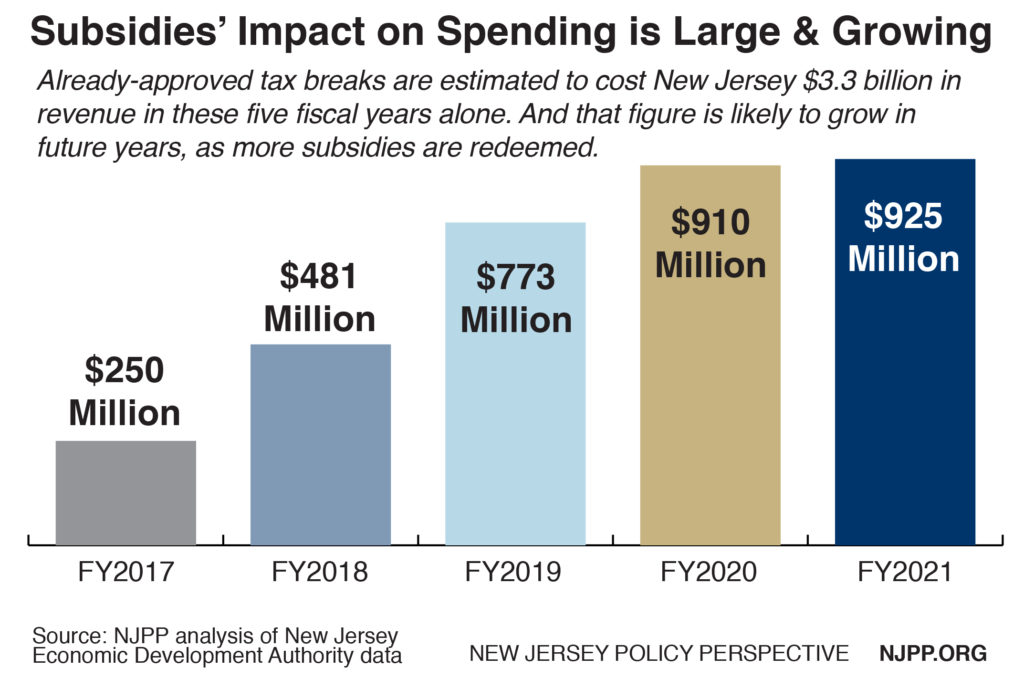

This surge in tax subsidies will create a long-term and growing drag on New Jersey’s economy, creating a significant problem that policymakers will have to grapple with for at least the next 15 years as the backlog of tax credits is paid out.

The tax breaks will cost New Jersey about $3.3 billion in fiscal years 2017 through 2021 alone, or an average of $668 million a year, according to Economic Development Authority (EDA) estimates.[9] And this is merely the tip of the iceberg in terms of the true long-term fiscal impact (see the recommendations for the shortcomings of these projections and how to improve them).

For a state that cannot meet its past and current obligations, that’s a dangerous amount of revenue that could be put to much better use by investing in the assets that, unlike tax breaks, are proven to grow New Jersey’s economy, like public colleges and transportation, or providing a stronger safety net for the growing numbers of working New Jersey families and children who are living in poverty.

And the negative impact on New Jersey’s finances is only going to grow after 2021, as more of the corporations who’ve been approved for tax breaks in recent years cash in. This natural lag time is the result of two factors: one, it generally takes a few years for approved projects to start delivering any jobs or capital investment and therefore receive any tax break; and two, most subsidy awards are over 10-year periods, which ensures that the revenue loss comes in smaller bites but lasts for a longer period of time. To wit: Of the $5.6 billion in future tax credits approved after the legislative overhaul, only $40.1 million – or less than 1 percent – has been redeemed to date, according to the EDA.[10]

What’s worse, despite the ballooning costs, only a narrow slice of New Jersey’s business community is granted such assistance – less than 300 of New Jersey’s approximately 200,000 businesses have received subsidies under the Economic Opportunity Act.[11] In other words, about two-tenths of 1 percent of New Jersey’s businesses have benefited from the tax shift that the subsidy programs create while the other 99-plus percent are left to make up for the revenue the state will lose.

Common-Sense Reforms Would Put Help New Jersey Back on Track

New Jersey’s policymakers need to control this surge in subsidies before more damage is done to the state’s economy and before the bills we’re passing on to future taxpayers become even larger. Reining in the use of tax breaks for large corporations would allow lawmakers to focus more on tried-and-true economic-development strategies like workforce development and job training; direct entrpreneurial assistance; and investments in public higher education and early education, or public transit – all of which offer much better return on the state’s investment than tax subsidies.[12]

While the Economic Opportunity Act expires in July 2019, there are immediate actions lawmakers should take to protect New Jersey’s future. One option is to simply move the law’s expiration date up, as a leading Republican lawmaker has proposed. Speaking to a reporter about her proposal to shift the expiration date to July 2017, Assemblywoman Amy Handlin rightly noted that “we need to fundamentally change the way we look at these kinds of initiatives if we’re going to keep some fiscal integrity in the state in future years.”[13]

Short of an early end to the programs, there are plenty of other ways New Jersey lawmakers can start to rebalance the economic-development scales.

Restore Spending Caps

Restoring spending caps on the total amount New Jersey can give in subsidies – not just how much a particular company can receive – would be a great victory for accountability and would increase the legislature’s key role in oversight. Caps – commonly applied before the 2013 overhaul – would prevent subsidy programs from growing beyond a predetermined amount without automatically attracting the attention of lawmakers. Currently, only one of New Jersey’s two subsidy programs has a cap (which has been increased twice through little-noticed bills); the other has no cap at all.

New Jersey should also create an annual cap on the amount of subsidies that can be approved. This helps prevent the program from hitting the overall cap earlier than expected and having it simply increased by legislators before the program expires, as it has in the past. New Jersey’s annual cap should follow the lead of Iowa’s, and be across all major tax subsidy programs administered by the Economic Development Authority.

Annual limits are “one of the strongest protections against surprise increases in tax incentive costs,” according to the Pew Charitable Trusts. Caps can be designed in different ways. In some states, subsidies are awarded on a first-come, first-served basis until a program runs out of money. This is typically how caps have worked in New Jersey. But there are other approaches too. In some states, all businesses seeking breaks apply at the same time, and the state chooses which will receive the subsidies and for how much. And in others, all subsidy-seekers that meet the basic program criteria are approved and receive a break, but the dollar value is prorated depending on how many other companies are approved.[14]

New Jersey should also consider implementing a lower dollars-per-job cap to avoid what’s often called “buffalo hunting” by economic development experts: spending lots of dollars on just a few companies and jobs. Sixteen subsidy programs in states from California to Oklahoma to Maryland impose a dollars-per-job cap of less than $10,000.[15] New Jersey’s current average award per job since December 2013 is close to $84,000 – and in Camden city, the subsidized jobs have a price tag of $276,000 each.

Mandate Better Reporting on Outcomes & Improve Evaluation

New Jersey has improved the information it provides to the public about state subsidies over the past few years, including producing annual reports on tax breaks and other tax expenditures since 2010, but a huge hole remains. The state also needs to honor a mandate to create a Unified Economic Development Budget, which is designed to provide more detailed information from all corporations receiving at least $100,000 in state subsidies, including how many jobs have been created, how much they pay, whether those jobs are full- or part-time and whether they include health coverage. The state Treasury Department has never produced this report, despite being required to do so by legislation passed in 2007.

After claiming for several years that it was in the works and would be forthcoming, Treasury changed course in 2014, telling the Office of Legislative Services that the report would require information that the state can’t share due to “agreements with the Internal Revenue Service respecting the safeguarding and sharing of confidential taxpayer information.”[16]

Legislation passed by the Assembly Budget Committee in October 2016 would make some important tweaks to the 2007 law, and – it appears – would allow Treasury to move forward with the production of this annual report. This bill current awaits a floor vote in the Assembly; it’s companion bill in the Senate is currently awaiting a hearing from the Budget and Appropriations Committee.[17]

Alternatively, the Economic Development Authority – which should have much of the information required by the statutorily-required report – should start producing a similar document each year on its own. Under pressure from advocates and lawmakers, the Authority has taken steps in this direction in the past year – but more robust reporting is still needed.[18]

In addition, New Jersey ought to create and sustain a robust, independent evaluation process to determine if these tax breaks are having the desired effect, or if they are falling short. The Garden State is one of 23 states identified as “trailing” when it comes to evaluating its subsidy programs, according to the Pew Charitable Trusts, which is widely recognized as the nation’s leading authority on evaluating tax breaks.

Despite making “billions of dollars in incentive commitments in recent years,” New Jersey “has not adopted a plan for regular evaluation of tax incentives,” Pew notes. While New Jersey has contracted with the Bloustein School at Rutgers University to undertake an evaluation of the state’s current subsidy offerings, Pew suggests more regular evaluation is required to “answer the questions that are most relevant [to the policy] debate, such as to what extent incentives influence business decisions as opposed to rewarding what companies would have done anyway, and how incentives are affecting net economic activity.”[19]

Last but not least, New Jersey lawmakers ought to require a more regular and longer-term forecasts of the budget impact of already-approved subsidies. Currently, the Economic Development Authority estimates the fiscal impact to the state for the current fiscal year and the next four, as part of the annual budget hearings process. (This forecast is the basis for the $3.3 billion in lost revenue figure cited earlier.)

First, this is a woefully short – and therefore incomplete – forecast, since nearly all approved tax breaks have a 10-year or even 20-year lifespan during which state revenue will be lost and since most projects receiving subsidies take a few years to come online and begin receiving their tax breaks. Second, this is in no way required by law; if the Office of Legislative Services decided to cease asking this question of the EDA, policymakers and the public would no longer get the information.

Lawmakers should require the EDA to provide 15-year forecasts, updated quarterly and posted on the EDA’s website. Alternately, the EDA should take the initiative and do this on its own. We recognize that the more years a forecast goes out, the less reliable the estimate is. But given the design of these tax breaks, the public and other interested parties deserve to know the best estimate of future revenue loss over the long term.

Fix the Net Benefits Test

Policymakers need to follow the lead of the Economic Development Authority and begin restoring some semblance of financial integrity to what’s known as the “net benefits test.” This is the statutory formula the EDA uses to estimate the economic benefits of any proposed tax break, using the number of proposed jobs, their promised wages and other factors. When designed properly, this is a basic taxpayer protection that ensures the state isn’t losing money on a subsidy deal. But in too many cases under the Economic Opportunity Act, the test offers little or no taxpayer protection.

Before 2013, to be approved for a tax break, most tax break projects had to deliver a benefit to the state of at least 110 percent – in other words, 10 percent more than the dollar value of the subsidy – over the same period (usually 15 years) that the company was committed to keeping the jobs in-state. If the corporation didn’t meet those promised obligations, it would receive less of a tax break, or none at all.

But under the Economic Opportunity Act, some projects receiving subsidies in Camden need only deliver a 100 percent benefit – in other words, break even – over 35 years. And the corporation is obligated to deliver the proposed jobs and economic activity for, at most, only 15 years. After that, it can move, slash its workforce, cut pay across the board, or threaten to move in order to receive yet another tax break – and the state would have no recourse to claw back any of the tax credits that had already been claimed. Moreover, think how far off projections made in 1982 about how business would be conducted and where by 2017 – think what besides driverless cars might be around the corner to affect how business everywhere is conducted.

As a result, when taken together, the 26 Grow New Jersey projects approved for Camden so far actually come with a risk to the state of losing $206 million, according to the EDA’s own internal numbers.[20] That stands in stark contrast to the “net benefit” of $777 million that is officially on the books and created by this implausible and unrealistic economic estimating formula.

As a result, when taken together, the 26 Grow New Jersey projects approved for Camden so far actually come with a risk to the state of losing $206 million, according to the EDA’s own internal numbers.[20] That stands in stark contrast to the “net benefit” of $777 million that is officially on the books and created by this implausible and unrealistic economic estimating formula.

And Camden isn’t the only area where a corporation could receive an incredibly lopsided benefit. In the four other cities the state considers to be most distressed – Atlantic City, Passaic, Paterson and Trenton – a project’s benefits must equal 110 percent of the tax break but are estimated over 30 years, which still creates a significant imbalance between taxpayer and corporate interests. So, an EDA-approved Atlantic City call center can collect $33 million in tax breaks over a 10 year period, shut its doors and move offshore after 15, with New Jersey taxpayers absorbing a $11 million loss and the state defenseless to do anything about it.

This winter, the EDA took an important step toward reducing risks by changing the rules of this “net benefits test.”[21]

Under the changes, which officially went into effect in April, the net benefits test would eliminate most – but not all – of the estimated economic benefits in the so-called “out years” (ie, the years when there is no guarantee a corporation will still be in New Jersey). And there is a window in which a corporation can ink an agreement with the EDA promising to stay beyond the official commitment period and still receive the larger subsidy. While this is not ideal, we are glad to see the proposed changes also include a clawback provision, by which the state can recoup some of the subsidy it’s already awarded if the corporation breaks a promise to stay beyond the official commitment period.

Tax break applicants will be subject to the new formula starting in July of this year. The change will not apply to the $1.5 billion in subsidized projects already approved in Camden.[22]

The EDA is to be applauded for its actions, but the real reform must come from the legislature and governor, as they write the law that governs these subsidies.

When it comes to this net benefits test, the legislature should follow the EDA’s lead and restore some fiscal responsibility and realism to the test. The easiest and most sensible way to do so would be to ensure that the net benefits test covers only the number of years the corporation is committed by statute to stay in the state, as legislation introduced by Assemblyman Troy Singleton would do.[23]

Eliminate, or Develop More Stringent Standards for, Subsidies for Existing Jobs

The practice of rewarding companies that threaten to leave New Jersey is short-sighted, as is the state’s increasing use of this “strategy.” Ideally, policymakers would eliminate state subsidies to “retain” existing jobs, but if they aren’t willing to take this common-sense step, they should at least develop more stringent standards that would limit subsidies for jobs supposedly at risk of being moved to another state.

One of the few positives of 2013’s subsidy overhaul was that it took a first step in this direction by finally treating retained jobs differently than new jobs. First, these jobs are now only eligible for 50 percent of the gross amount of tax credits that a new job at the same facility would be. Second, the number of jobs that must be retained for a company to be eligible for a subsidy is higher than the number of new jobs required at a firm that is relocating. For example, a company moving here from Connecticut must bring only 10 new jobs to qualify for a subsidy, while a company already here would have to keep 25 existing jobs to be eligible for the same award. (There are, however, loopholes that effectively eliminate any difference between new and existing jobs in certain situations.[24])

In addition, the Economic Development Authority adopted new regulations that would help ensure that professional-service jobs (accountants, attorneys and the like) and their support staff aren’t eligible to be deemed “at-risk” jobs.[25] This makes a lot of sense, because much like your local pizza parlor, accountants and other professionals with local customer bases and expertise about Jersey-centric laws and regulations aren’t going to leave New Jersey in pursuit of lower taxes in other states.

But policymakers should do more. They should build on this progress by placing a cap on the percentage of subsidy dollars that can go to existing jobs. Ideally, this cap would reflect the minimal economic growth created by retaining jobs, as well as the obvious fact that not all threats to leave the state are real – we suggest 10 percent of gross tax credits as a good place to start.

Other Reforms

New Jersey policymakers should also:

Put Subsidies in the State Budget: Approving a lucrative tax credit program for corporations is an easy choice for policymakers when they don’t have to appropriate any money and can point to their efforts as having done something to help the economy (even if that’s not the case). It needs to be a harder choice. Putting all of New Jersey’s subsidy programs into the budget process – even if only by making legislators specify the dollars to be spent on tax credit redemptions each year – would promote a better debate about the best ways to best to foster broad prosperity in New Jersey.

Restrict Corporations’ Ability to Redeem More in Credits Than They Owe in Taxes: New Jersey allows subsidy-receiving corporations to sell their tax credits to an entity that owes the state taxes. This enables the sellers to receive far more money in subsidies than they actually owe in taxes, which is overly generous and violates the spirit behind tax breaks. In New Jersey, businesses were approved to transfer or sell $247 million in tax credits between 2013 and 2016.[26] Some states are considering putting an end to this practice “as a way to keep costs under control,” according to the Pew Charitable Trusts.[27] In New Jersey, even nonprofit corporations – which are exempt from state corporate taxes to begin with – receive subsidies and boost their own revenues by selling those tax credits to taxpaying businesses. This practice should be ended, and soon. Barring corporations from selling excess tax credits is a common-sense step New Jersey policymakers should take to rein in excessive costs.

Ensure Fair Wages: A key positive provision of the Economic Opportunity Act of 2013 bill would have ensured that custodial, security and building maintenance workers on any project or development that received tax credits be paid no less than the prevailing wage for that industry or sector. Unfortunately, this was the only provision of the original legislation that the governor conditionally vetoed, and it never became a reality. As a result, New Jersey is at risk of subsidizing employers who offer unlivable wages related to many of these projects.

Prevent Extra Rewards for Known Federal Tax Dodgers: New Jersey should not allow corporations that take advantage of “inversions” – the tax-avoidance scheme of a larger U.S. corporation merging with a smaller foreign company to avoid U.S. taxes – to also receive state tax breaks. Under current law, the state is at risk of a double whammy: a company’s federal tax avoidance produces a lower state tax base, which is again reduced by generous tax breaks handed out by the Economic Development Authority. While New Jersey policymakers can’t change federal tax policy on inversions, they can take small but important steps to protect New Jersey’s tax base and limit the state’s rewards for bad corporate behavior.

Include Automatic Sunset Provisions:The Economic Opportunity Act rightly includes an automatic expiration – or sunset provision – for both active subsidy programs. This is important because it forces policymakers to reconsider the tax breaks to see if they are meeting their goals, rather than allowing the subsidies to continue without further examination. When considering future subsidy programs, the legislature should be sure to include this provision. Or, better yet, the state could adopt umbrella legislation that would place an automatic sunset on all subsidy programs.

Cooperate With, Rather Than Compete Against, New Jersey’s Neighbors: Instead of operating in a vacuum that ends at New Jersey’s borders, policymakers and leaders should develop a mutually beneficial subsidy policy with our neighboring states rather than competing with them to move jobs back and forth, as their colleagues in the Kansas City area are trying to do.[28] Doing so could allow the entire region to move forward with an economic-development strategy that would benefit all partners, rather than benefiting one state at the expense of another and doing nothing for the region as a whole.

Endnotes

[1] Good Jobs First and the Iowa Policy Project, Selling Snake Oil to the States, November 2012.

[2] See, for example, Area Development magazine’s annual survey of corporate executives. In 2016, “highway accessibility” (ie, location) and “availability of skilled labor” were ranked the top factors for site selection. “State and local tax incentives” and “corporate tax rate” were ranked fifth and sixth, respectively. http://www.areadevelopment.com/Corporate-Consultants-Survey-Results/Q1-2017/highway-accessibility-tops-list-Charles-Ruby-Deloitte-Tax.shtml

[3] Urban Institute, State Economic Development Strategies: A Discussion Framework, April 2017.

[4] Main Street Alliance, Voices of Main Street, October 2015.

[5] NJPP analysis of 2015 US Census Bureau American Community Survey data.

[6] New Jersey Policy Perspective, New Jersey’s Sluggish Recovery Hurting Working Families, September 2016.

[7] New Jersey Policy Perspective and Economic Policy Institute analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics employment data.

[8] NJPP analysis of New Jersey Economic Development Authority public data, accessed via the EDA website’s “Incentives Activity Reports” in late April 2017. The data is up-to-date through the April 2017 EDA meeting.

[9] New Jersey Economic Development Authority, Response to Office of Legislative Services Questions in Fiscal Year 2018 Budget Hearings, May 2017.

[10] New Jersey Economic Development Authority, Completed and Certified Incentive Projects, April 2017.

[11] New Jersey had 194,184 firms in 2013, the most recent year for which data is available from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Statistics of U.S. Businesses. http://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/susb.html

[12] See W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, Cost-Effectiveness of Alternative Economic Development Policies (September 2009), Urban Institute, State Economic Development Strategies: A Discussion Framework (April 2017) and Good Jobs First, Smart Skills versus Mindless Megadeals, (September 2016).

[13] Politico New Jersey, GOP Lawmaker Aims to End Economic Incentives She Supported, February 2017.

[14] Pew Charitable Trusts, Reducing Budget Risks, December 2015.

[15] Good Jobs First, Smart Skills versus Mindless Megadeals, September 2016.

[16] New Jersey Office of Legislative Services, Treasury Department Response to Questions, May 2014.

[17] The bills in question are A-301 (http://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2016/Bills/A0500/301_R2.PDF) and S-2744 (http://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2016/Bills/S3000/2744_I1.PDF)

[18] New Jersey Policy Perspective, A Step in the Right Direction: EDA Adds Some Results to its Tax Subsidy Reporting, May 2015.

[19] Pew Charitable Trusts, How States Are Improving Tax Incentives for Jobs and Growth, May 2017.

[20] NJPP analysis of New Jersey Economic Development Authority “net benefits tests” for each Camden deal; obtained via the Open Public Records Act.

[21] New Jersey Register (Volume 49, Issue 8), Rule Adoptions – Economic Development Authority – Adopted Amendments: N.J.A.C. 19:31-18.3 and 18.10, April 2017.

[22] Ibid 9

[23] Assembly Bill Number 328, http://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2016/Bills/A0500/328_R1.PDF

[24] New Jersey Policy Perspective, New Jersey’s Subsidy Overhaul: One Step Forward, Five Steps Back, August 2013.

[25] New Jersey Register (Volume 49, Issue 1), Rule Adoptions – Economic Development Authority – Adopted Amendments: N.J.A.C. 19:31-18.3 Eligibility Criteria, January 2017.

[26] Ibid 9

[27] Ibid 14

[28] New Jersey Policy Perspective, Kansas & Missouri Work Towards Tax Subsidy Ceasefire, August 2016.