Concern about the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, along with renewed fears about school shootings, have put the mental health of New Jersey’s students into the spotlight.[i] Federal data show 74 percent of public schools in the Northeast report an increase in students seeking mental health services since the start of the pandemic.[ii] The state Legislature has responded by introducing several bills that directly address the need for schools to take an active role in identifying and treating student mental health issues.[iii]

Given these serious concerns, it is important to assess recent trends in New Jersey schools’ capacity to address students’ mental health. This report looks at these trends through a racial justice lens, specifically addressing this question: How has access to school mental health staff changed for Black, white, Hispanic/Latinx, Asian, and other students over the past decade?

Analysis of the available data shows a clear trend: While access to mental health staff for white and Asian students has increased over the past several years, it has decreased for Black students. A decade ago, Black and Hispanic/Latinx students had an advantage over white students in access to mental health staff; now white students have the advantage (albeit a small one).

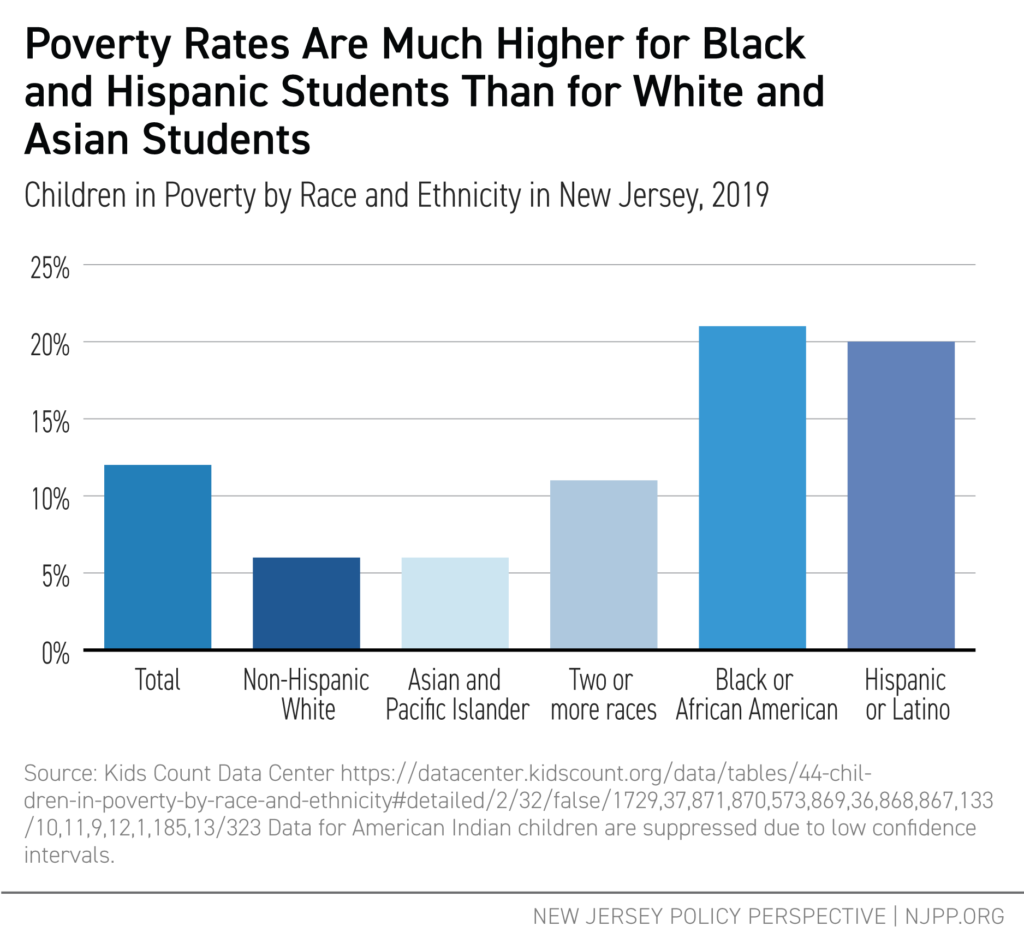

Given New Jersey’s much higher poverty rates for children of color, and the profound influence poverty has on mental health, these trends are a cause for great concern. Additionally, studies show that school districts that enroll more students of color are more likely to impose disciplinary actions on their students, compounding this growing inequity. In other words: New Jersey’s Black and Hispanic/Latinx students are more likely to live in poverty and more likely to be suspended from school, even as their access to mental health professionals is decreasing.

Uneven Access to Mental Health Staff

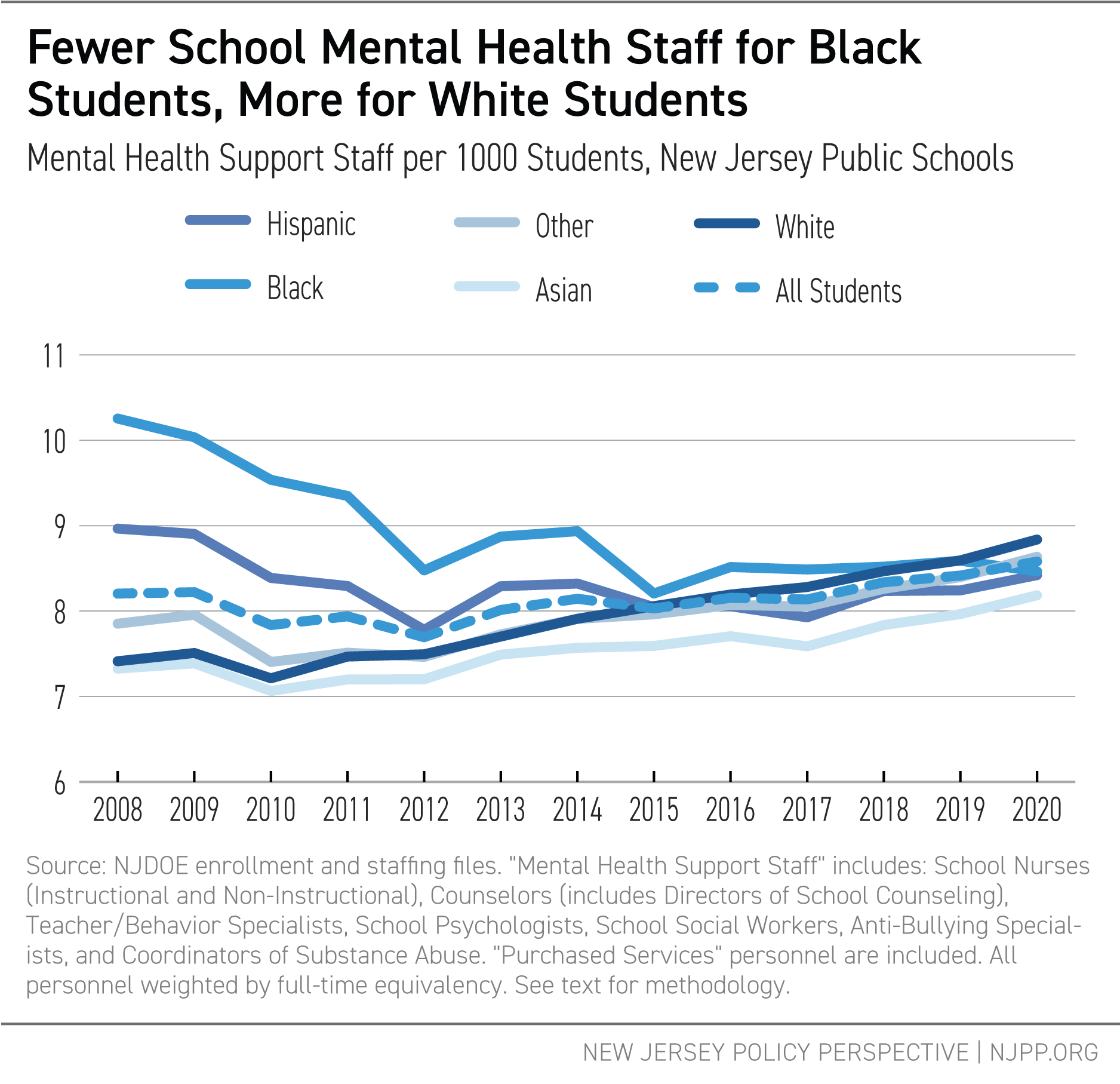

Student mental health problems can be identified and treated by a variety of school staff. We include the following positions in the overall category of school mental health staff: nurses, counselors, psychologists, social workers, anti-bullying specialists, and substance use coordinators. The figure below shows the changes since 2008 in access to these staff for students of different races and ethnicities (see the “Methodology” section below for details).

In 2008, all public schools in New Jersey had, on average, 8.2 mental health staff per 1,000 students; this rose to 8.6 staff per 1,000 in 2020. During the same period, mental health staff per 1,000 white students rose from 7.4 to 8.5.

In contrast, mental health staff per 1,000 Black students decreased from 10.3 to 8.5. For Hispanic/Latinx students, the figures declined from 9.0 to 8.4 per 1,000. In other words: During a period where access to mental health staff increased for New Jersey’s white and Asian students, access for Black and Hispanic/Latinx students decreased.

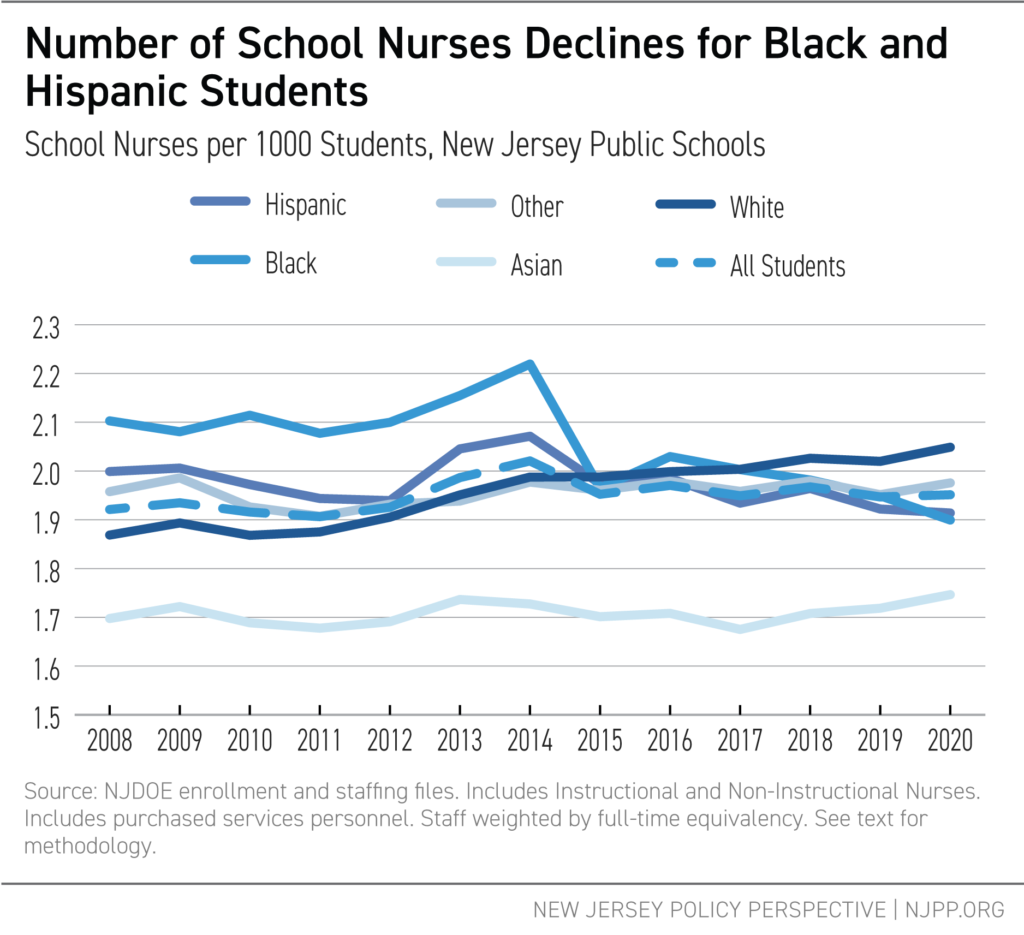

These trends have not been uniform across all mental health staff positions. The figure below shows trends by race/ethnicity for school nurses: while the number of nurses per 1,000 students has increased for white students, it has declined for Black and Hispanic/Latinx students. Notably, nurse staffing for Asian students remains considerably lower than for other races/ethnicities.

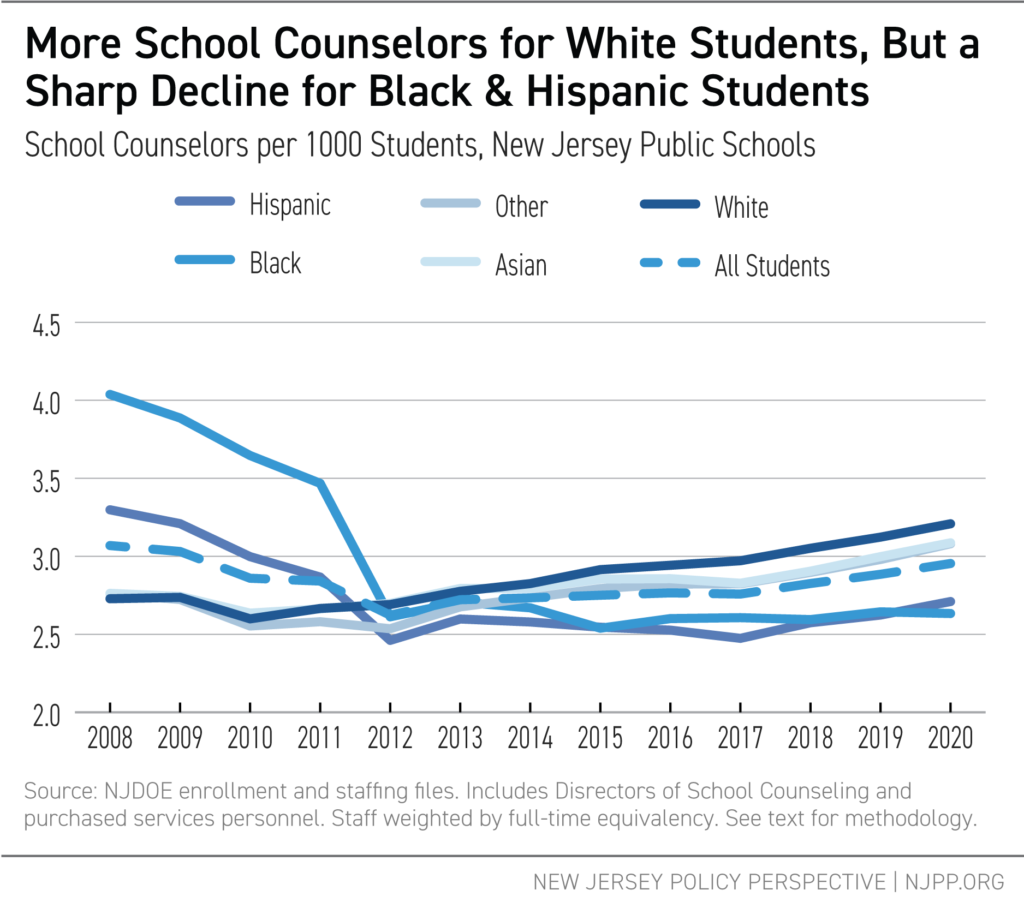

Over the same period, school counselor staffing has changed dramatically. In 2008, there were 2.7 counselors per 1,000 white students; this rose to 3.2 per 1,000 by 2020. In contrast, Black students had 4 counselors per 1,000 in 2008; this dropped to 2.6 per 1,000 by 2020. It should be noted that the American School Counselor Association recommends 4 counselors per 1,000 students; overall, New Jersey remains far behind this goal.[iv]

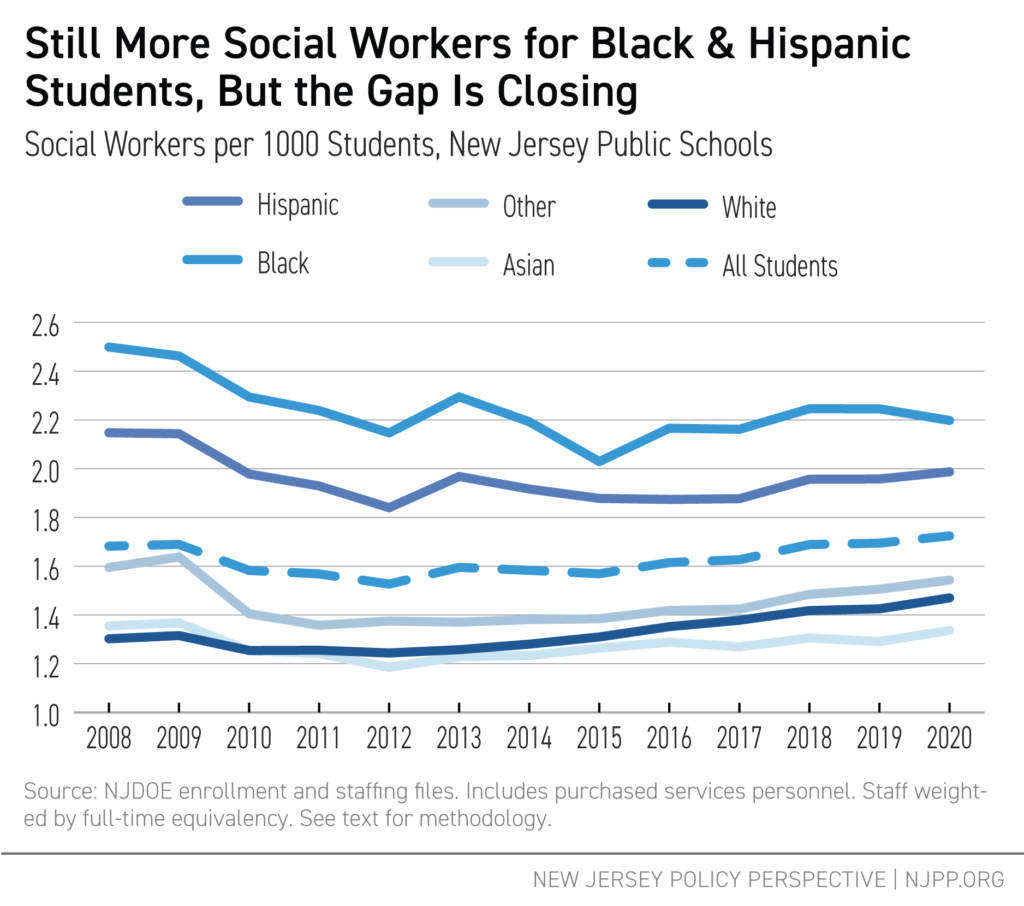

Black and Hispanic/Latinx students still have an advantage in social workers per 1,000 students over white and Asian students. The gap, however, is narrowing, as the number of social workers for Black and Hispanic/Latinx students has declined.

Why Mental Health Staffing for Schools Matters, Especially for Students of Color

Some may argue that these trends in school mental health staffing reflect a move toward parity: A decade ago, white students had less access to these staff than children of color, but now their access is equivalent. This argument, however, fails to recognize a basic truth: New Jersey’s students of color are more likely to live in poverty than the state’s white students and, as a result, have greater mental health needs.

The poverty rates for Black/African-American and Hispanic/Latinx children are more than three times that for white or Asian children. This is critical, as a large body of research shows poverty has a profoundly negative impact on children’s mental health.[v] Certainly, more school mental health staff for white and Asian students would be, by itself, laudable; however, the accompanying trend of less access to these staff for Black and Hispanic/Latinx students raises serious concerns.

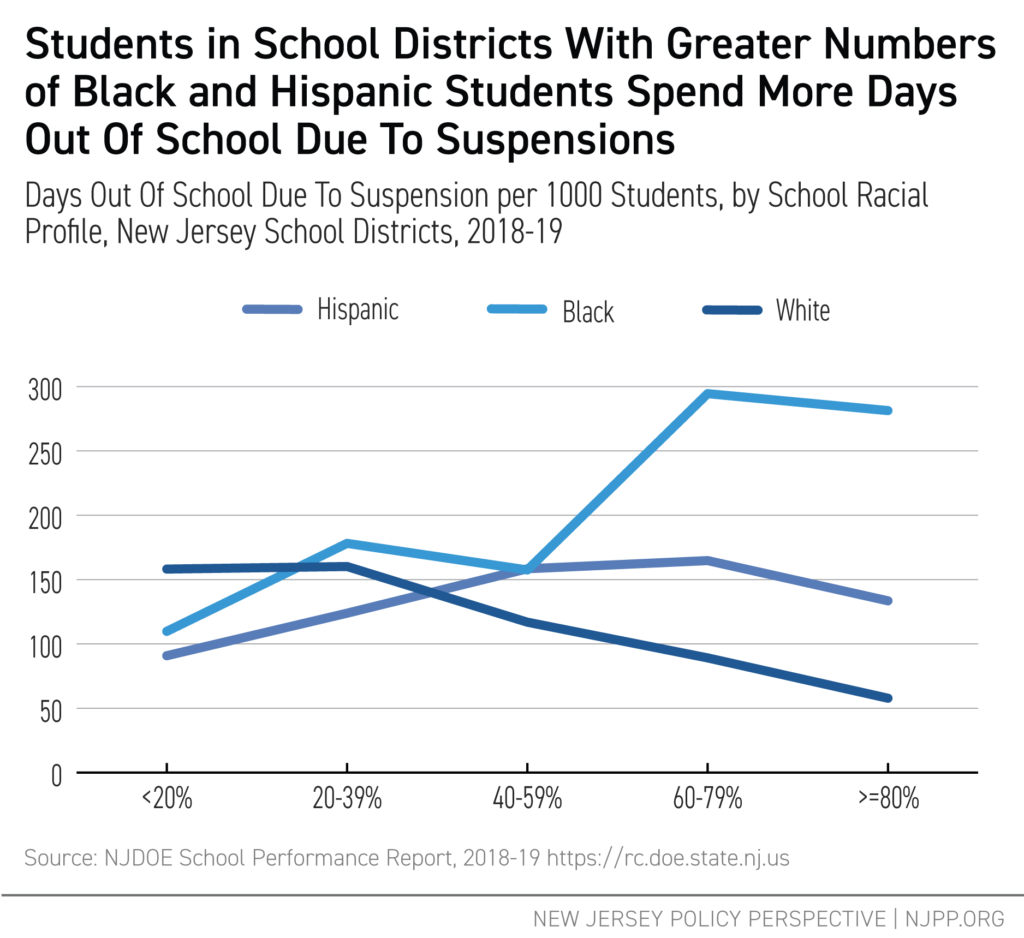

It is important to note that greater poverty rates and decreasing access to mental health staff for students of color are occurring in an environment where those same students are more likely to suffer harsh disciplinary consequences.

As a New Jersey school district’s percentage of white students increases, it is, on average, less likely to have students miss school due to a disciplinary suspension.[vi] In contrast, schools with higher percentages of Black or Hispanic/Latinx students tend to have their students miss more days of school due to suspension. Research shows a clear link between student mental health and school discipline: when students feel supported and safe in school, disciplinary consequences diminish.[vii] The unequal discipline meted out to students of color is, therefore, yet another indicator that they are not getting access to the mental health supports they need.

As NJPP has previously reported, greater access to school staff of all sorts is directly influenced by school funding policies.[viii] Yet New Jersey’s students of color are much more likely to attend schools that are underfunded, according to the state’s own law, than white students.[ix] While the short-term infusion of federal school funds tied to the pandemic could help schools reverse trends in mental health staffing for students of color over a short period, longer-term funding solutions are necessary.

Such funding, however, should be guided by analyses like the one above. Lawmakers will not be able to address staffing trends that are racially unequal unless and until they are aware of them. Monitoring the deployment of school personnel of all types by student race—and by other student characteristics—should be the regular and ongoing work of policymakers.

Methodology

This report relies on two data sources from the New Jersey Department of Education: staffing files (obtained through Open Public Records Act requests) and enrollment files (available publicly at: https://www.nj.gov/education/doedata/enr/). All staffing files observations represent a school staffer, each with an accompanying job code. I aggregate the workers in different jobs for each school district (weighted by full-time equivalency); I then divide that aggregate by the total number of students in the district. These fractions of a staffer are then assigned to each student regardless of race/ethnicity. The numbers of students and the fractions of staff are then totaled across the state for each race/ethnicity category, as well as for all students. These figures are used to generate the “staff per 1,000 students” figures found in this report.

End Notes

[i] Wall, Patrick. (8/23/21) “How schools are racing to respond to a mental health crisis.” NJ Spotlight News. https://www.njspotlightnews.org/2021/08/student-mental-health-needs-nj-schools-response-pandemic/

[ii] 2022 School Pulse Panel, April findings. Institute of Education Sciences. https://ies.ed.gov/schoolsurvey/spp/#tab-4

[iii] Donyéa, Tennyson (6/10/22) “N.J. committee approves new school safety, teen mental health measures.” WHYY. https://whyy.org/articles/n-j-school-safety-teen-mental-health/

[iv] American School Counselor Association. “School Counselor Roles & Ratios” https://www.schoolcounselor.org/About-School-Counseling/School-Counselor-Roles-Ratios “Since 1965, ASCA has recommended a student-to-school counselor ratio of 250:1.” This translates to 4 counselors per 1,000 students.

[v] Schmidt, K. L., Merrill, S. M., Gill, R., Miller, G. E., Gadermann, A. M., & Kobor, M. S. (2021). Society to cell: How child poverty gets “Under the Skin” to influence child development and lifelong health. Developmental Review, 61, 100983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2021.100983

Gibson, K., Abraham, Q., Asher, I., Black, R., Turner, N., Waitoki, W., McMillan, N., Child Poverty Action Group (N.Z.), & New Zealand Psychological Society. (2017). Child poverty and mental health: A literature review. http://www.cpag.org.nz/assets/170516%20CPAGChildPovertyandMentalHealthreport-CS6_WEB.pdf

Evans, G. W. (2016). Childhood poverty and adult psychological well-being. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(52), 14949–14952. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1604756114

Coley, R. J., & Baker, B. D. (2013). Poverty and Education: Finding the Way Forward. ETS. https://www.ets.org/research/policy_research_reports/publications/report/2013/jqkw

[vi] We use data from the 2018-19 school year as this was the last full school year before the covid-19 pandemic caused school closures.

[vii] Prins, S. J., Kajeepeta, S., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Branas, C. C., Metsch, L. R., & Russell, S. T. (2022). School Health Predictors of the School-to-Prison Pipeline: Substance Use and Developmental Risk and Resilience Factors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 70(3), 463–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.09.032 https://www.jahonline.org/article/S1054-139X(21)00491-2/fulltext

[viii] Weber, M. (2021) The Consequences of School Underfunding. New Jersey Policy Perspective: Trenton, NJ. https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/the-consequences-of-school-underfunding/

[ix] Weber, M. & Baker, B. (2020) School Funding in New Jersey: A Fair Future for All. New Jersey Policy Perspective: Trenton, NJ. https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/school-funding-in-new-jersey-a-fair-future-for-all/