To download a PDF of this report, click here.

Limiting the ability of profitable multistate corporations to use accounting gimmicks to avoid New Jersey taxes would help level the playing field for the state’s small and local businesses. This important reform, known as “combined reporting,” is so common in other states that nearly all of New Jersey’s largest employers already use it when filing state taxes elsewhere.

Most large corporations consist of a parent entity and its subsidiaries. Combined reporting treats the parent company and subsidiaries of multistate corporations as one entity for state corporate income tax purposes. Their nationwide profits are added together and the state then taxes the appropriate share of the combined income. With recent enactment in Rhode Island and Connecticut, 25 out of the 45 states that have some form of corporate income taxation, plus the District of Columbia, now mandate combined reporting.

Most large corporations consist of a parent entity and its subsidiaries. Combined reporting treats the parent company and subsidiaries of multistate corporations as one entity for state corporate income tax purposes. Their nationwide profits are added together and the state then taxes the appropriate share of the combined income. With recent enactment in Rhode Island and Connecticut, 25 out of the 45 states that have some form of corporate income taxation, plus the District of Columbia, now mandate combined reporting.

Members of both political parties have introduced legislation[1] that would build upon New Jersey’s 2002 Business Tax Reform Act, which banned deductions for royalties paid to related out-of-state companies and required combined reporting by all casinos and any corporation suspected of abuse by the Division of Taxation. Making combined reporting mandatory for all multistate corporations is a common-sense step that would stop profitable multistate corporations from taking advantage of the tax loopholes that remain in place. And it potentially would raise between $235 and $470 million a year for much-needed investment in schools, roads and other building blocks of a strong economy.[2]

Despite the continued opposition of some business lobbyists, there is no better evidence of the benign economic development impact of combined reporting than the continued willingness of major multistate corporations to maintain operations in combined reporting states. Large corporations continue to willingly locate or expand in states with combined reporting.[3] And for the vast majority of the largest corporations in New Jersey, combined reporting is nothing out of the ordinary and is accepted as another cost of doing business.

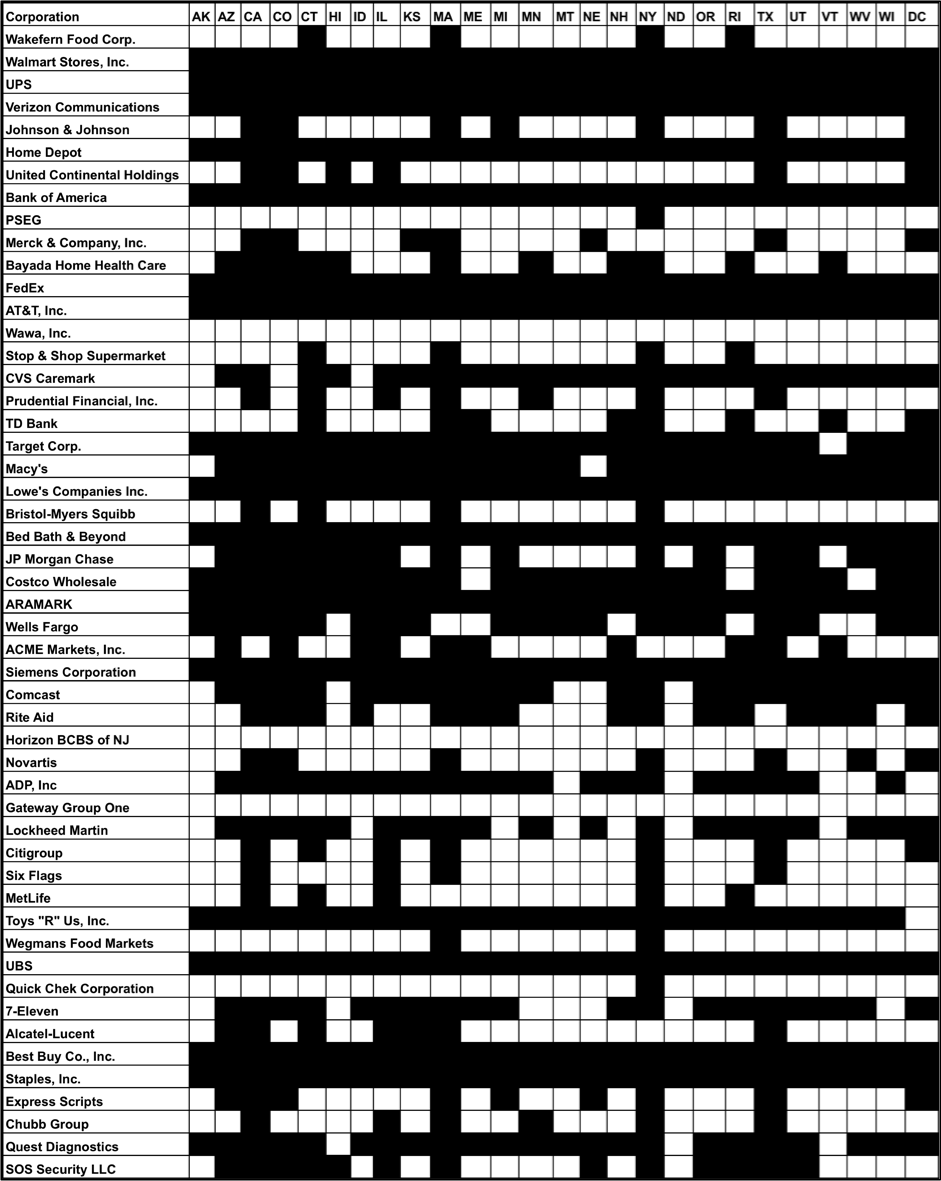

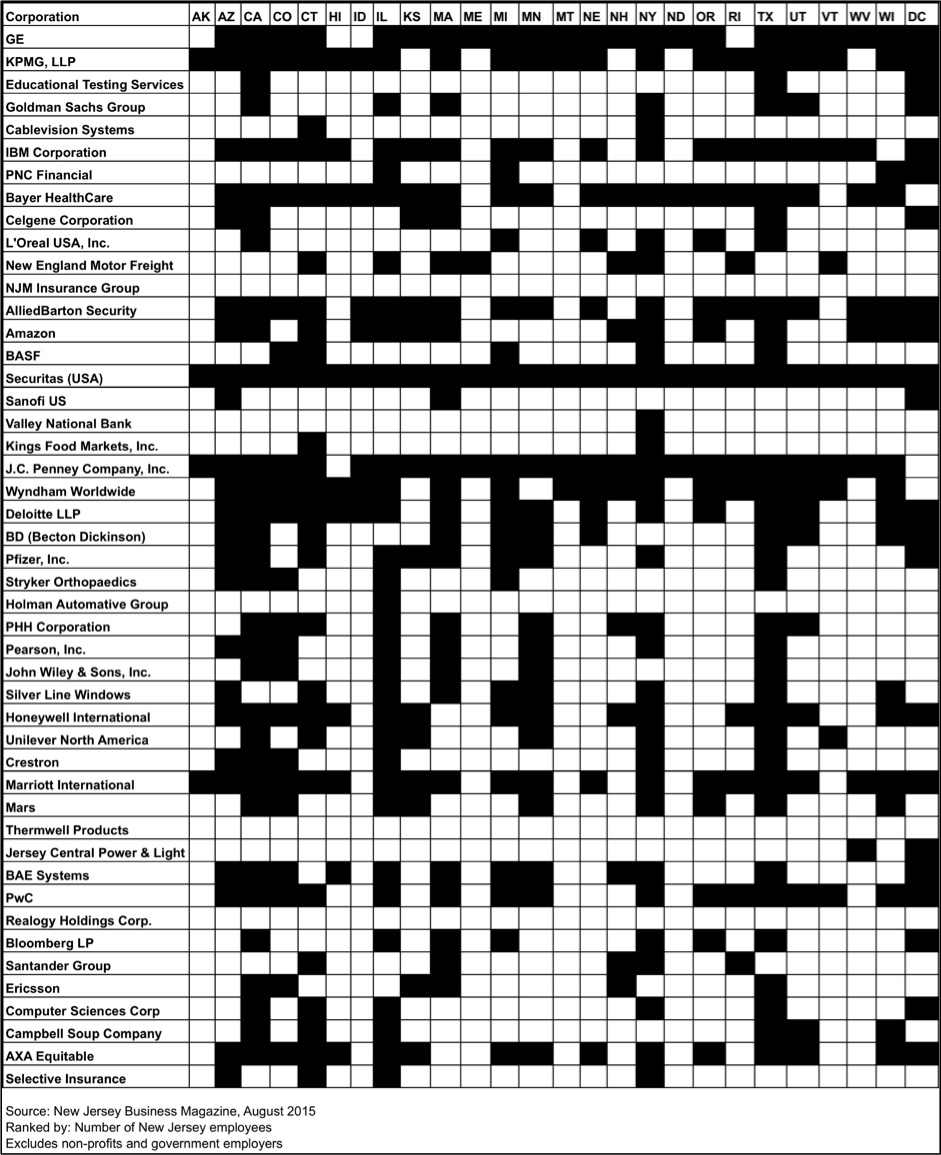

New Jersey’s 98 largest non-casino for-profit employers were examined by NJPP to see in what other states they have physical facilities (casinos are already subject to combined reporting in New Jersey). These include the state’s largest financial institutions, pharmaceutical companies and retailers. (See Appendix for full breakdown by employer.)

• Nearly all of the largest New Jersey employers – 92 out of 98 – maintain facilities in at least one combined reporting state or are a member of a corporate group that has a facility in at least one combined reporting state. (94 percent)

• The vast majority of these corporations maintain facilities in multiple combined reporting states. More than 75 percent – 76 out of 98 – have facilities in five or more combined reporting states and about half – 48 out of 98 – have facilities in 10 or more such states.

• Fifteen of these companies have facilities in all 25 combined reporting states as well as Washington, D.C. (15 percent)

• Of the 10 largest employers, all have facilities in at least one combined reporting state – and half of them have facilities in all 25 combined reporting states as well as Washington, D.C.

• More than one in three of the companies maintain their headquarters in combined reporting states (36 percent). These include Verizon, AT&T, United, Target and Pfizer.

• Three out of four companies – 73 out of 98 – have a facility in California, the state that pioneered combined reporting and is known to enforce it most aggressively. (75 percent)

In other words, it is very clear that adopting comprehensive combined reporting would not lead New Jersey’s largest employers to leave the state or discount New Jersey as a location for future investment.

In fact, expanding combined reporting would nullify a sophisticated real estate scheme used by Walmart and other multistate retailers and banks. Combined reporting would also reduce the competitive disadvantage faced by small businesses operating in New Jersey. As it stands, local businesses are more likely to have to pay taxes on all their profits, because, unlike multistate firms, they have nowhere to shift them. Even unincorporated businesses not subject to corporate income tax may be at a disadvantage without combined reporting because their profits are subject to the state’s personal income tax. Without combined reporting, large multistate corporations end up paying income tax at a lower effective tax rate than small businesses.

Combined reporting not only helps foster a more level playing field for all businesses, it increases the resources that states need to be able to invest in vital services like education, transportation infrastructure and public safety – services that all businesses rely upon and consider when making long-term plans. Failing to mandate combined reporting could harm the state’s economy by allowing its corporate tax base to erode, undermining the public services needed by the private sector.

Some major multistate corporations oppose combined reporting, claiming it leads to difficult and costly tax compliance burdens. These corporations also threaten that combined reporting could lead to job losses if major employers leave the state or reject it for future investments.

This rings hollow, considering the evidence presented here. Most of New Jersey’s largest employers already operate in combined reporting states and, in some cases, have been for decades. As an accounting process, there is little difference between combined reporting and the consolidated reporting that the vast majority of large corporations use when they report their profits to the Internal Revenue Service and stockholders. Multi-entity corporate groups are the only ones affected by combined reporting, and the very small increase in complexity is well justified by the need for New Jersey to stop corporate tax sheltering. Concerns over the possibility of comprehensive combined reporting creating an undue burden on corporations are therefore unfounded.

Appendix: Detailed Breakdown by Employer and Industry

Finance

Every one of the 16 largest New Jersey companies that specialize in professional financial services operates in at least one combined reporting state. Half of them are located in 15 or more combined reporting states, and half are headquartered in a combined reporting state.

Retail

Retail giants like Walmart, Lowe’s and CVS have a strong presence in New Jersey. With the exception of Wawa, all 27 of the largest retailers in the Garden State operate in at least one combined reporting state (96 percent).

Three in four of these retailers – 20 out of 27 – have operations in at least a dozen combined reporting states, while 11 (41 percent) have facilities in all 25 combined reporting states. Ten have their headquarters in a combined reporting state.

Many of the state’s largest retailers are also headquartered here. Two of them – Toys “R” Us and Bed Bath & Beyond – are in every combined reporting state. Other New Jersey-based retailers already familiar with combined reporting because they operate in at least one combined reporting state include the state’s biggest employer, Wakefern Food (owner of Shop Rite and Price Rite), Quick Chek and King Food Markets.

Pharma/Biotech

All of New Jersey’s largest pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies, like Merck and Bayer, are subject to combined reporting since they all operate in at least three locations that require the tax policy. And seven of the nine (78 percent) have facilities in five or more combined reporting states.

Methodology

This study is modeled on similar studies of Maryland and New Mexico conducted by Michael Mazerov, a Senior Fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities in Washington, D.C. and one prepared for Connecticut Voices for Children by the Yale Law School Legislative Advocacy Clinic. The methodology used is based on guidelines shared by Mr. Mazerov, but the accuracy of the findings is the sole responsibility of NJPP.

The 98 businesses examined for this report were culled from the New Jersey Business & Industry Association’s annual list of New Jersey’s 100 largest for-profit employers by number of employees.[4]

NJBIA’s 2015 list of largest for-profit employers actually includes 104 businesses. However, we excluded six casino operations from the analysis, because they are already subjected to combined reporting in the Garden State as a result of corporate tax reform passed in 2002.[5]

The two main sources of information used to identify the states in which the companies have facilities were the annual “10-K” reports filed by publicly traded corporations with the Securities & Exchange Commission and the companies’ websites. The 10-K report contains a section called “Properties,” which frequently includes a company’s description of its major facilities. This information was supplemented by an examination of each company’s own website.

Many company websites include a section specifically listing their locations. For those companies that did not have such a page, it was often possible to use the company’s career page for more information. Here, companies often list all their locations to assist prospective employees in their job search. If not, states were included in the analysis only if there were multiple job listings for each state. Job listings for sales jobs were disregarded because the presence of sales personnel in a state does not automatically establish corporate income tax liability for a company.[6]

The data in this analysis should be viewed as a minimum number of combined reporting states in which New Jersey companies and their corporate parents are taxable. States were counted only if written evidence authored by the company itself that it had a facility in a specific combined reporting state was obtained and double-checked. It is quite possible that some companies in this analysis are subject to corporate income tax in other combined reporting states. Finally, it is possible that some of the companies listed in the analysis are not subject to New Jersey corporate income tax – and therefore outside the reach of the state’s adoption of combined reporting – because they are structured as Limited Liability Companies or Subchapter S corporations.

Endnotes

[1] Senators Lesniak, Sarlo and Greenstein have introduced Senate Bill 61, while Assemblyman Dancer has introduced Assembly Bill 1720.

[2] New Jersey Policy Perspective, Closing Corporate Tax Loopholes Would Help New Jersey’s Small Businesses & Provide Resources to Build Economy, June 2015.

[3] For example, see research from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (http://www.cbpp.org/research/vastmajority-of-large-maryland-corporations-are-already-subject-to-combined-reportingin?fa=view&id=3317), Connecticut Voices for Children (http://www.ctvoices.org/sites/default/files/bud10combinedreporting.pdf), and the Institute for Wisconsin’s Future (http://wisconsinsfuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/iwf_combined_report_feb09.pdf)

[4] New Jersey Business and Industry Association’s New Jersey Business magazine, 43rd Annual Top 100 Employers, August 2015.

[5] Public Law 2002, C. 40

[6] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Most Large North Carolina Manufacturers Are Already Subject to ‘Combined Reporting’ in Other States, January 2009.