Picture a child living in New Jersey. Think about what that child needs to grow up safe, healthy, and educated. The child will need food and clothing, a roof over their head, regular doctor’s visits, child care, and before- and after-care if they’re in school — not to mention transportation to and from those places. Given that many families across the income spectrum need help covering these costs,[i] New Jersey should create its own state-level child tax credit to make the Garden State a more affordable place to start a family.

The success of the expanded federal Child Tax Credit has shown how a simple solution — a monthly tax-refund check for families with children — can reduce food insecurity, avoid debt, and improve savings, keeping 3 million children out of poverty.[ii] Building on previous federal tax credits has a strong record of success in New Jersey, notably with the state Earned Income Tax Credit, which boosts the take-home pay for hard-working, low-paid families statewide.

A state-level child tax credit would recognize the unique costs of raising children and the support that most families need to care for their kids and set them up for success. When families can pay for basic expenses and save for their children’s futures, it improves child well-being immediately by reducing key costs like food and rent, makes it more likely for children to reach their full potential, and reduces societal costs created by child poverty later in life.

To support this proposal, NJPP analyzed the benefits of multiple state tax credit scenarios for families based on overall number of people reached, race/ethnicity, and income level.

Based on this analysis, NJPP determined that an effective program, like the current federal program, would start from some basic foundational points:

- Fully refundable credit going directly to households with children

- Relatively simple eligibility

- Must avoid perverse incentive of lower-income families getting less help

The two scenarios presented in this report are inspired by the federal expanded Child Tax Credit, focusing on children in low-income and middle-income families — one targeting all families earning less than 250 percent of the federal poverty level (about $69,000 for a family of four, or $58,000 for a family of three)[iii], and one only available to young children up to five years old in the same income range. Both proposals cost roughly $100 million.

Each scenario serves a slightly different group of people, but both scenarios have key features that make them work for New Jersey families, including:

- Money goes directly to hundreds of thousands of families with children to support their basic needs

- Most of the money goes to the bottom 50 percent of New Jersey families in terms of income

- Improving race equity because Black and Hispanic/Latinx families make up such a large share of this group

NJPP’s modeled tax credit proposals also include two significant groups of people excluded from the federal Child Tax Credit — children with Individual Tax Identification Numbers and adult dependent children under age 25.

New Jersey will be a stronger state with greater opportunity when every family can provide a safe, healthy life for their children. A state-level Child Tax Credit modeled on either scenario would support families, aid in child development, and — in the process — make the state tax system more equitable.

The Problem: Child Poverty and the High Costs of Raising a Family

New Jersey’s poverty rate remains stubbornly high at 10 percent.[iv] Nineteen states have a lower child poverty rate than New Jersey, which ranks in line with lower-income states like West Virginia, Indiana, and Ohio.[v] For a family of four renting a home in New Jersey, that’s an income of $30,150.[vi]

How does such a high-income state end up with 1 in 10 children living in poverty?

The answer is no surprise — New Jersey’s high cost of living, especially housing costs — which strain the budgets of low-paid families more than in other states. One way to measure housing burden is a household spending more than 30 percent of its income on rent, mortgage, or housing-related expenses such as insurance or taxes. Based on this metric, 76 percent of New Jersey low-income households have a high housing cost burden, even more than such other high-cost states as New York, California, and Massachusetts.[vii]

With such a large chunk of earnings eaten up by such basic costs as housing and child care, New Jersey families with children need a helping hand to meet other basic needs. Many studies over the years document how difficult it is for even middle-income families in New Jersey to make ends meet and pay for routine costs of child-rearing, including the United Way of Northern New Jersey’s ALICE (Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed) report, and Legal Services of New Jersey’s True Poverty rate report. These reports make clear that official governmental poverty measures so badly underestimate the extent to which families struggle to get by as to provide an incomplete picture of financial hardship in New Jersey. The bottom line: many families well above the official “poverty” line can’t make ends meet.

Because of these high costs, the federal Child Tax Credit, even if it is expanded again, will be inadequate to support many New Jersey children. The federal program does not account for varying cost of living from state to state. Families at a specific income level get the same amount of support in any state, even though that income goes much farther in some states than others. A state-level Child Tax Credit could help more families meet basic needs costs such as rent, food, and bills, while freeing up funds to pay down debt.

Living in poverty has dire consequences for the life trajectory of New Jersey children, and higher child poverty rates among Black and Hispanic/Latinx children exacerbate existing inequities among the adult population, especially among young children. Young Black and Hispanic/Latinx children are three to four times more likely to live in poverty than their white counterparts.[viii] These disparities are driven by past and current policy factors such as discrimination in home loans and hiring, school segregation and underfunding, and entrenched wealth inequality.[ix]

And the racial disparity in poverty compounds existing inequities. Children experiencing poverty are more likely to experience:

- Adverse childhood experiences

- Worse physical health

- Structural changes in brain development

- Decreased educational attainment

- Increased risky behaviors[x]

Beyond the costs that children bear themselves, society suffers when children suffer. Children in poverty are less likely to reach their maximum potential, and higher long-term costs like health care are shared by society as a whole. One recent estimate pegged the costs of child poverty in the U.S. at $1 trillion, roughly a quarter of the annual federal budget.[xi] The overwhelming weight of evidence shows that exposure to poverty, especially early in life and for prolonged periods, harms children in the moment and for the rest of their lives.[xii]

Why Refundable Child Tax Credits Can Help Families Meet Basic Needs

Refundable child tax credits complement existing public investments in children and families in key ways:

- Filling in gaps left behind by other programs

- Ensuring aid goes to families who need it most

- Limiting red tape by paying families directly through the tax system

Before diving into these benefits, though, a bit of terminology. Tax credits allow taxpayers to subtract certain amounts from their total tax bill. These are different from deductions (which allow taxpayers to reduce their taxable income) in that taxpayers can directly remove credits from the amount they owe in taxes.

A refundable tax credit means that even if a taxpayer has no end-of-year tax bill or already gets a refund from the government after tax is calculated, the taxpayer still receives the credit as part of their refund.

For the bulk of taxpayers who receive a refund after filing their taxes (roughly half of New Jersey full-time state income tax returns in 2016),[xiii] tax credits only help if they are refundable.

Tax Credits Fill In Gaps Left by Existing Programs

Refundable child tax credits reduce child poverty differently from other anti-poverty programs, like health insurance or food assistance, by putting cash directly in the pockets of families — all without new onerous applications or requirements, as the program uses data in the existing tax filing system.

The new refundable federal Child Tax Credit provides a prime example of how such credits can reduce child poverty. As part of the American Rescue Plan, the Child Tax Credit has provided historic relief to almost 90 percent of America’s children, reducing child poverty by almost half nationally.[xiv] The Child Tax Credit has also reduced food insecurity by more than a quarter among households with children nationally.[xv] These benefits came in the form of direct IRS tax relief payments either directly into bank accounts used for prior tax refunds or as checks to families.

The effectiveness of the Child Tax Credit in child poverty reduction lies in its almost-revolutionary simplicity. Unlike other traditional programs, a refundable Child Tax Credit’s payments are based on essentially only two inputs: their income on their tax returns and the number of child dependents they can claim. By streamlining the process of getting support out the door, the fully refundable Child Tax Credit has provided instant poverty relief for the majority of eligible households in just a few months.[xvi]

The federal expanded Child Tax Credit provides a blueprint for how a state-level credit might function. Because the IRS has banking and mailing address information for all households that submitted tax returns in the past two years, the agency could identify households with children below the income cap and distribute benefits payments accordingly. States could replicate this process through their tax agencies, sending checks out just like tax rebate checks.

Full Refundability Means Tax Relief Goes to Those Who Need It Most

Refundable tax credits allow all taxpayers to collect the full amount of the credit, regardless of whether they qualify for a refund at the end of their tax filing. This is critical for reaching low-income families, who often have lower income tax liabilities but still need the benefits provided by the credit. For example, New Jersey’s Homestead Benefit provides a refundable tax credit for property tax payers, recognizing that even though a property owner may have relatively little income and therefore little income tax liability, they still need assistance in paying their property taxes.[xvii]

Conversely, a tax credit that is only partially refundable or completely non-refundable does little to assist those taxpayers who would already receive a refund. For example, prior to the passage of the American Rescue Plan, the federal Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit allowed taxpayers with children under 13 or other dependents to claim up to $600 for one qualifying individual and $1,200 for two or more individuals. This seems like a substantial benefit for low-income families. But because it was nonrefundable, only those taxpayers who had liability at the end of the tax year received the benefits.

The results: Households with higher incomes made more dependent-care claims than low-income households, despite making up less of the population. By being nonrefundable, a tax credit designed to defray child care expenses ended up directing most of its aid to higher-income families. Recognizing the limitations of nonrefundable credits, the American Rescue Plan converted the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit to a refundable credit for the 2021 tax year.[xviii]

Making a state tax credit fully refundable maximizes how much the credit helps the low-income families and children who need it most, without complex new means-testing requirements. A fully refundable child tax credit would also ensure that lower-income families do not perversely get penalized and receive less in assistance than higher-income ones.

Lower Administrative Costs for State Government and Applicants

Child Tax Credits do not have an onerous application process because the agency administering the program bases its payment on information provided in tax returns. Based solely on income and the age and number of children in a household, the agency would be able to calculate the benefit amount and send out the money via check or direct-deposit, the same way it already does with tax rebate checks.

This contrasts with most programs providing benefits to families and children, which require extensive application processes, including in-person interviews, health or financial disclosures, and other information that families may not have easily on hand.

These program restrictions mean many families that should or could qualify for programs often do not receive the benefits they are entitled to or simply do not participate. For example:

- Only 16 percent of people living in poverty participated in New Jersey’s TANF cash assistance program.[xix]

- Only 70 percent of working people in poverty participated in SNAP in New Jersey.[xx]

Additionally, a tax credit program requires relatively little staffing or overhead at the state level, given that it is largely a pass-through of cash from tax collections back into residents’ pockets.

Child Tax Credit Design Decisions

Small details in Child Tax Credit design can create substantial changes in the number of children reached, how much they receive and, ultimately, how much the program reduces poverty.

Income-Targeting vs. Universal

Almost all social safety net programs must balance targeting benefits to lower-income households with extending benefits to all families who may need them, even in the middle- and upper-income ranges.

In the U.S., states with child tax credits often set eligibility based on a range of incomes, with Maryland limiting the credit to the lowest-income families (below $6,000) while Idaho has no income limit at all.[xxi] For an overview of child tax credits at the state level, the National Conference of State Legislatures has an overview of current state tax credits.

Age-Targeting

Generally speaking, state and local governments provide the bulk of their benefits for children through the K-12 school system.[xxii] By one measure, New Jersey spends roughly 78 percent of its public investments in children in the Pre-K-12 education system.[xxiii] But this leaves out younger children, with very little investment in infants and toddlers.

Some states with Child Tax Credits limit eligibility by age.[xxiv] California and Colorado both provide credits specifically for children 5 years old and under.[xxv] The federal Child Tax Credit expansion also includes a 20-percent higher benefit for children under 6 ($3,000 maximum credit for children ages 6-17 and $3,600 for children under six years old).[xxvi]

When a child is born, their costs are introduced all at once, shocking family finances at a pivotal point in their parents’ economic lives.[xxvii] Young children are more likely to live in poverty than their older counterparts.[xxviii]

Targeting a tax credit to younger ages might help those parents at a critical point in their children’s lives before substantial public investment in public schools. But the costs of children do span their entire lifetimes, not just the early years.

Smaller Regular Payments vs. Annual Lump Sum

The expanded federal Child Tax Credit provided advance monthly payments administered by the Internal Revenue Service.[xxix] Different child allowance systems globally provide the benefit annually, monthly, bi-weekly, or at some other frequency, while some programs allow the claimant to elect for one version or another.[xxx]

Given the relatively small benefit amount of most scenarios NJPP tested, the annual lump sum is more likely to alleviate family costs. In early research on the EITC — when the benefit was much lower than it is today — many families preferred annual lump sum payments.[xxxi] However, a new child tax credit program should provide options with different frequency of benefits delivery, in order to determine whether the frequency affects spending, well-being, or whether families simply prefer one kind to the other.

Phase-Outs

Assuming the full amount of the refundable credit is available to any household earning any taxable income in the year, the question then becomes how and when to phase the credit out. As with other benefits, a steep cliff where benefits go from a maximum amount to vanishing creates perverse economic incentives where it may be more beneficial to stay under an income threshold.[xxxii]

A smooth benefits phase-out can gradually reduce the benefit as a percentage of additional income. But determining where and how the phase-out should begin and end is an open question. And because this is a tax program, the determination will largely be based on annual gross income, rather than poverty status (which is based on the number of individuals living in the household). Nonetheless, the federal Child Tax Credit’s phase outs offer some guidance, with one phase-out for the expanded credit starting at $150,000 for joint-filers and $75,000 for single-filers, while the complete phase-out of the original credit starts at $400,000/$200,000 for joint/single filers and reduces the credit eventually to zero as income increases.

On the one hand, a lower-dollar phase-out targets benefits to lower-income households. On the other hand, stretching the phase-out into higher income ranges may better reflect the higher cost of living in New Jersey. The question of targeting versus universality is essentially functionalized in the question of phase-outs.

Eligibility

The federal Child Tax Credit expansion notably leaves out two key groups: children without a Social Security Number and adult dependent children. Only children with Social Security Numbers, ages 16 and under, are eligible to be claimed.

Children Without a Social Security Number

Roughly 6 percent of New Jersey children are foreign-born, compared to about 3 percent nationally.[xxxiii] Given that the purpose of a Child Tax Credit is to help families receive tax relief to alleviate the high cost of child-rearing, there is no economic distinction between foreign-born and U.S.-born children. Immigrant children must be housed, fed, clothed, and cared for, just like U.S.-born children, regardless of their citizenship.

Nonetheless, noncitizen children are often excluded from the patchwork of child financial supports that exist. For example, immigrant children have also missed out on a wide range of federal COVID-19 relief.[xxxiv] Even citizen children whose noncitizen parents work and file taxes are ineligible to receive benefits through the Earned Income Tax Credit, even after the American Rescue Plan improvements.[xxxv]

Procedures exist to allow children to be included in tax relief. The IRS provides a process to apply for tax ID numbers for minors, even those that do not earn enough income to file taxes.[xxxvi]

Given New Jersey’s diversity, there is no functional reason to exclude otherwise-eligible children from receiving tax relief for basic necessities.

Young Adult Dependents

Federal tax law allows certain adult children to be counted as dependent children, including children up to age 19, children in college up to age 24, and children with qualifying disabilities of any age. However, the new federal Child Tax Credit only applies to children ages 0 to 17.

If an adult child is listed as a dependent, they have low enough income that their parents must still pay for more than half of their basic necessities.[xxxvii] Young adults in this age range are often left behind in tax relief programs, receiving comparatively less in direct public benefits.[xxxviii] Yet, the poverty rate among young adults is the highest for any age range in the United States.[xxxix]

Including adult dependent student children up to age 24 in a Child Tax Credit can help close this benefits gap.

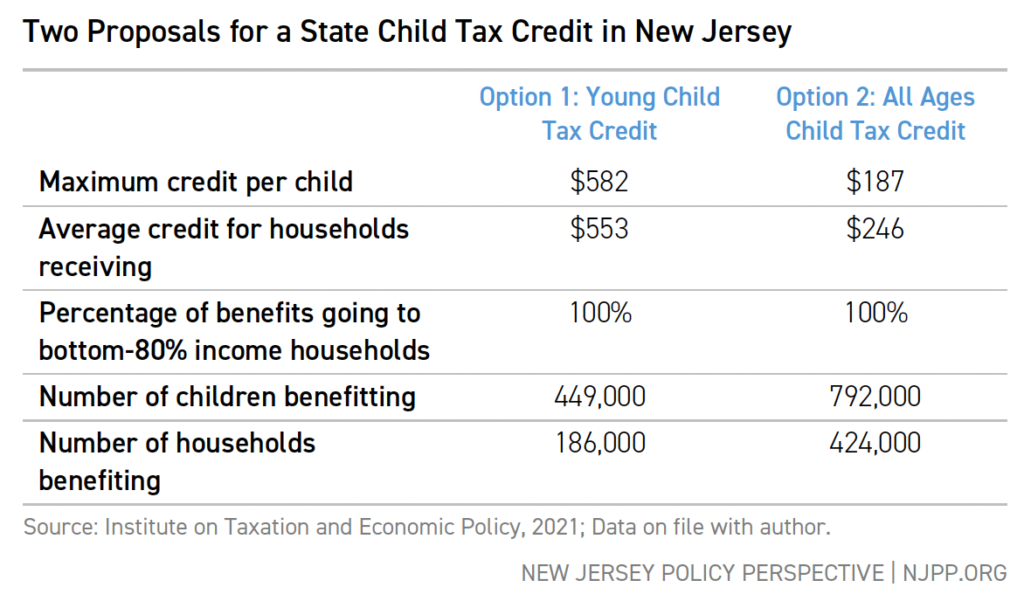

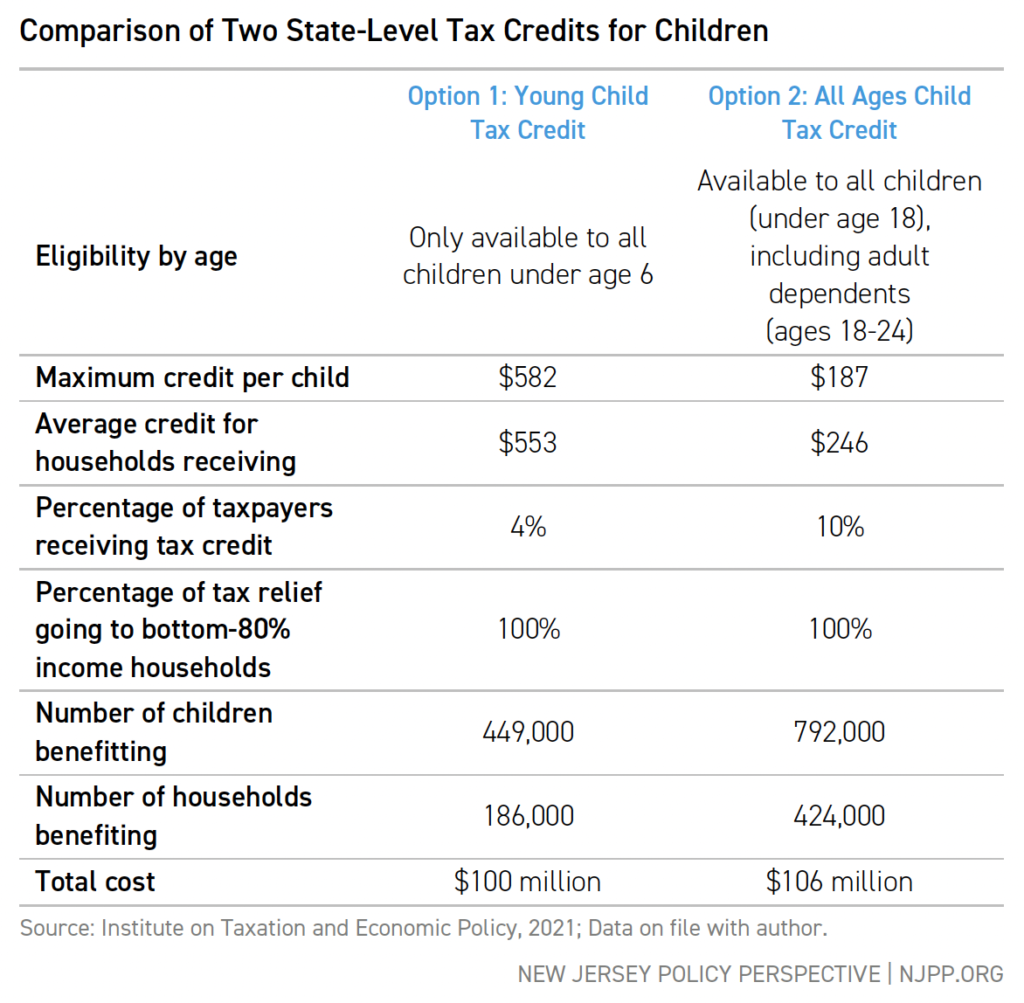

Two Proposals for a New Jersey Child Tax Credit

To model a potential refundable Child Tax Credit for New Jersey, NJPP uses the federal expanded Child Tax Credit as a baseline, then sets the rough cost to the state of $100 million. For comparison, the state EITC costs roughly $486 million, while the state Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit costs roughly $11 million. The cost modeling below was conducted by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP).

Given the relatively modest outlay of $100 million (by comparison, the federal expanded CTC payments totaled over $1.5 billion in New Jersey in just four months of the year-long program), the proposals have to target a smaller population.[xl]

The phase-out at 250 percent of the federal poverty level was based on research showing that New Jersey’s high cost of living makes a basic-needs budget substantially higher than the traditional federal poverty level.[xli]

NJPP outlines two versions of this credit for low-income New Jersey families — one targeted towards young children (up to age 5) only, and another that includes all children under 18 (and adult dependents up to age 24).

Option 1: Young Child Tax Credit

The proposed “Young Child Tax Credit” helps correct for systemic underinvestment in young children as a part of state spending. New Jersey’s young child poverty rate is routinely one or two percentage points higher than the poverty rate for older children.[xlii] The bulk of state and local spending on children in New Jersey goes to K-12 education, which dwarfs other spending substantially.[xliii] Some of this disparity was recognized in the federal expanded Child Tax Credit, which included an additional $600 of tax credit for children under age 6. California has created an entire Young Child Tax Credit to address this same issue.[xliv]

Directing aid to families with young children addresses the higher poverty rates among young children’s families. This age-targeting will also increase the benefit amount per child by shrinking the pool of eligible children. Although this small credit will not be nearly enough to cover all the expenses of young children, it can help fill in the gaps left behind by other programs. For example, SNAP, WIC, and other food support programs do not cover diapers, a substantial expense for children in this age range.[xlv]

Option 2: All Ages Child Tax Credit

Alternatively, a broader age range would cover more children but provide less per child. This proposal ensures that all families with dependent children get some aid, even if payments only cover a fraction of the true cost of child-rearing. This model would also include adult dependent children up to age 24, who are in school and/or earn so little work income that they qualify as the taxpayer’s dependents.

This universality has advantages, particularly the recognition that regardless of current levels of government program spending by age range, families often need financial support to cover basic needs for their children. The costs of children do not evaporate entirely when they enter K-12 schooling. Continuing the payment through later ages also ensures stable payments rather than a short-term patch, allowing families to plan around it as they do the EITC and other tax credits.

Comparison of Two State-Level Tax Credits for Children

Both credits are provided at the full amount for each eligible child in families up to 100% federal poverty level phasing out to $0 at 250% federal poverty level.

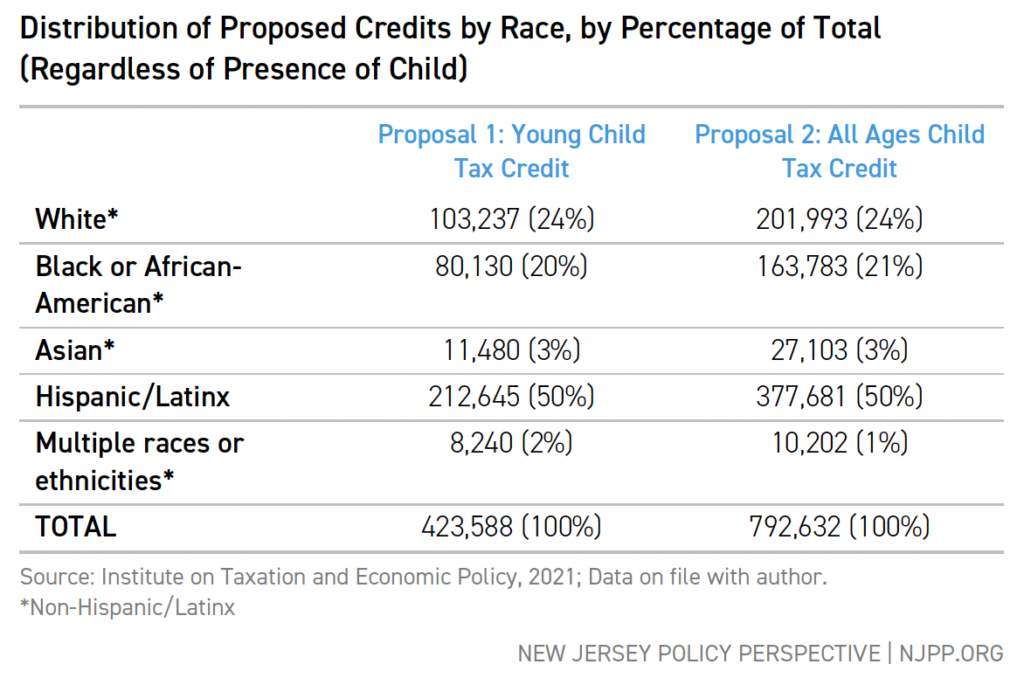

Both Proposals Would Improve Race and Income Equity for Children

Racial income and wealth inequality begins from the moment a child is born in New Jersey, because of systemic injustices, ranging from housing discrimination to wealth inequality. A Child Tax Credit focused on low- and middle-income families would help address some of these inequities while benefiting most New Jersey children.

That is, all households with children benefit regardless of race, especially households with multiple children. But because of the overrepresentation of Black and Hispanic/Latinx families and children in lower income ranges, Black and Hispanic/Latinx households receive a higher share of the tax benefit.

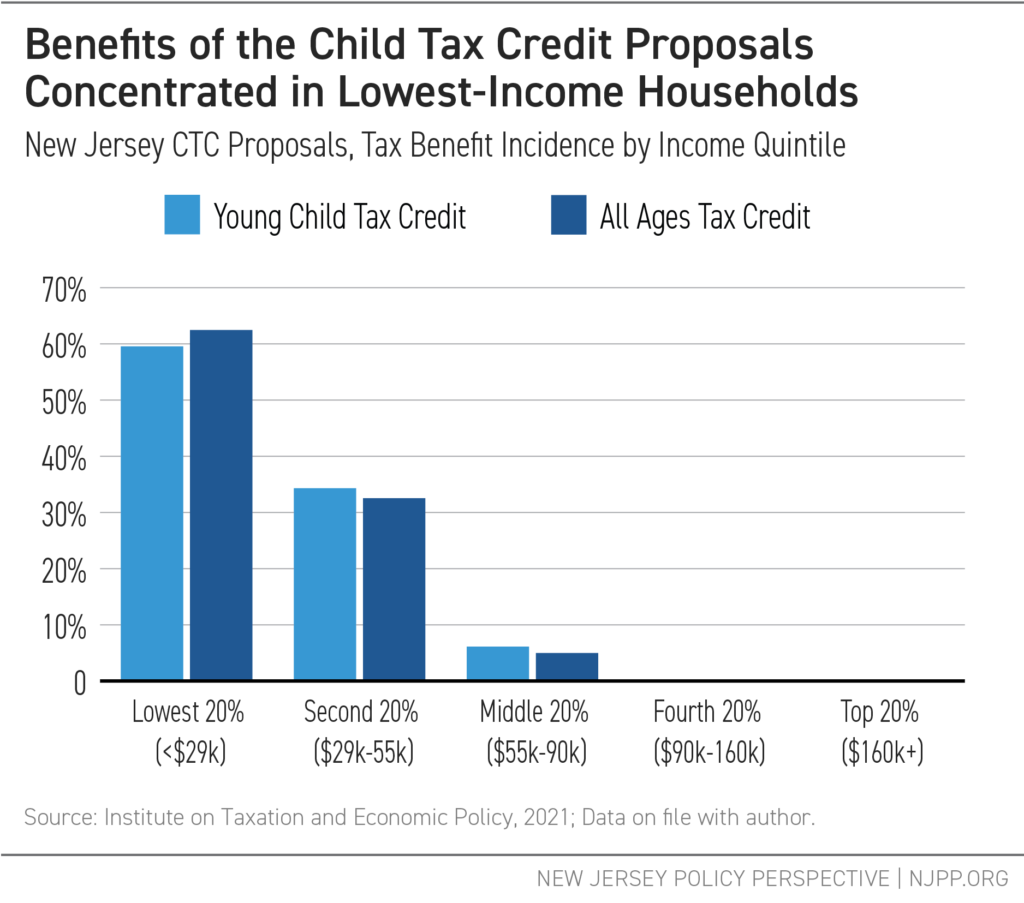

Both Proposals Would Target Low- and Moderate-Income Families

In both scenarios, the cap at 250 percent of the federal poverty level means that the entire tax benefit is concentrated in the bottom 60 percent of New Jersey households with incomes below $90,000.

Recommendations

New Jersey should pass a state-level fully refundable Child Tax Credit to provide cash relief to working families with children to help them meet the high costs of raising children in New Jersey. The credit is an investment in families and children to achieve their full potential and reduce the economic costs of child poverty. Although not a substitute for other community investments, a Child Tax Credit can close existing gaps in programs, while getting investment directly into communities that are under-resourced.

These proposals are a starting point for how New Jersey can ensure that children get what they need from day one, and provide a generalized child tax credit that is not linked to a specific program, use, or parental attributes.

In its FY 2023 budget, New Jersey should include this Child Tax Credit with the following features:

- Fully refundable for all eligible families. As described above, full refundability without preconditions or additional requirements is critical to ensuring that children can have their needs met. Anything short of full refundability creates perverse inequality that disproportionately hurts children living in the lowest-income households.

- Focus on low-income and middle-income families. Although the federal Child Tax Credit includes many families in higher income ranges, New Jersey’s more limited fiscal toolbox makes this program a better fit for a smaller population to maximize each credit’s impact. However, families should remain eligible even if their income goes past the range traditionally considered “low-income” (200 percent of federal poverty levels), given New Jersey’s high cost of living.

- Easy, user-friendly eligibility determination. Rather than juggle work requirements or complicated income calculations, a straightforward child tax credit should be easy for all working families in New Jersey to complete and easy for the state tax agency to calculate and distribute from existing records.

- Expanded eligibility to include groups excluded by the federal CTC. All children need food, shelter, clothing, health care, and education. These have costs on all children regardless of the happenstance of their place of birth. A state-level Child Tax Credit should include a method for child dependents without a Social Security Number to be claimed.

- Substantial outreach for free tax filing and non-filing support. In many ways this prong may be the most important. New Jersey and the federal government already use the tax code to distribute tax relief. Yet, many families are unaware of these benefits or deterred from using existing filing or non-filer portal systems. A state-level child tax credit should include a budget for outreach to potentially eligible taxpayers as well as grants to community organizations in high-poverty communities to assist parents and caregivers. This could build on existing services like Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA) and online services like MyFreeTaxes.com.

Conclusion

New Jersey’s competitiveness and long-term success as a state depend on ensuring that raising children in New Jersey can be affordable for working families across the income spectrum, not just the wealthy.

Using either of these two proposals as a base, a state-level Child Tax Credit would provide a huge win for New Jersey families by reducing high costs for low- and middle-income families raising children in the state, helping to close New Jersey’s pernicious racial child poverty gap, and building resilience among children to succeed later in life and mitigating the harms of poverty on child development.

End Notes

[i] As of 2018, the Bureau of Economic Analysis Regional Price Parity calculation estimated that New Jersey residents pay roughly 13 percent more for goods and services than the national average. See Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Economic Research Division, Cost of Living Calculator, available at https://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/cost-of-living/calculator (retrieved on November 9, 2021)

[ii] Zachary Parolin et al., Center on Poverty and Social Policy, Monthly Poverty Rates Among Children After the Expansion of the Child Tax Credit, 5 Poverty & Social Policy Brief No. 4, at p. 3, available at https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5743308460b5e922a25a6dc7/t/612014f2e6deed08adb03e18/1629492468260/Monthly-Poverty-with-CTC-July-CPSP-2021.pdf

[iii] U.S. Dep’t of Health and Human Services, HHS Poverty Guidelines fo 2022, available at https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/poverty-economic-mobility/poverty-guidelines

[iv] NJPP, when possible, uses the Supplemental Poverty Measure. Kids Count Data Center, Children in Poverty According to the Supplemental Poverty Measure, https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/11230-children-in-poverty-according-to-the-supplemental-poverty-measure#ranking/2/any/true/1985/any/21625 (retrieved November 9, 2021)

[v] NJPP, when possible, uses the Supplemental Poverty Measure. Kids Count Data Center, Children in Poverty According to the Supplemental Poverty Measure, https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/11230-children-in-poverty-according-to-the-supplemental-poverty-measure#ranking/2/any/true/1985/any/21625 (retrieved November 9, 2021)

[vi] Liana E. Fox and Kaylee Burns, The Supplemental Poverty Measure: 2020, September 2021, at p. 29, available at https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2021/demo/p60-275.pdf.

[vii] Kids Count Data Center, Children in Low-Income Households with a High Housing Cost Burden in the United States, https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/71-children-in-low-income-households-with-a-high-housing-cost-burden#ranking/2/any/true/1729/any/377 (retrieved November 9, 2021)

[viii] American Community Survey 5-year averages for 2015-2019 indicate poverty rates for Black children under age 5 at 27% and for Hispanic/Latinx children under age 5 at 24.7%, while white non-Hispanic children have a 7.8% rate. For a helpful summary, see the New Jersey Department of Health’s State Health Assessment Data indicator report for children under five years of age living in poverty, available at https://www-doh.state.nj.us/doh-shad/indicator/complete_profile/EPHT_LT5_pov.html

[ix] Areeba Haider, Center for American Progress, The Basic Facts about Children in Poverty, January 2021, available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/poverty/reports/2021/01/12/494506/basic-facts-children-poverty/

[x] The National Academies of Sciences published an extensive report on child poverty, summarizing existing research and proposing evidence-based solutions. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty (2019), available at https://www.nap.edu/read/25246/. This list is derived from that report’s summarized findings. Ibid. at 73.

[xi] Michael McLaughlin & Mark R. Rank, Estimating the Economic Cost of Childhood Poverty in the United States, 42 Social Work Research 73 (2018), available at https://academic.oup.com/swr/article-abstract/42/2/73/4956930?redirectedFrom=fulltext.

[xii] See National Academies of Sciences report at 89, https://www.nap.edu/read/25246/chapter/5#89.

[xiii] State of New Jersey, Department of the Treasury, Office of Revenue and Economic Analysis, Statistics of Income: 2016 Gross Income Tax Returns (2019) at Table D, “Cash Payments Summary by Return Type”, https://www.state.nj.us/treasury/taxation/pdf/pubs/soi-tables2016.pdf

[xiv] Congressional Research Service, The Child Tax Credit: The Impact of the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA; P.L. 117-2) Expansion on Income and Poverty, July 13, 2021, at p. 12, available at https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46839.

[xv]Claire Zippel, After Child Tax Credit Payments Begin, Many More Families Have Enough to Eat, Off the Charts Blog, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 30, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/after-child-tax-credit-payments-begin-many-more-families-have-enough-to-eat.

[xvi] The American Rescue Plan Act was signed into law on March 11, 2021. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1319/text Child Tax Credit payments began July 2021. https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/irs-monthly-child-tax-credit-payments-begin

[xvii] New Jersey Division of Taxation, How Homestead Benefits Are Calculated, July 16, 2021, https://www.state.nj.us/treasury/taxation/homestead/hrhomeowneramounts.shtml

[xviii] Congressional Research Service, The Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (CDCTC): Temporary Expansion for 2021 Under the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA; P.L. 117-2), May 10, 2021, at . 2, available at https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN11645

[xix] Laura Meyer & Ife Floyd, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Cash Assistance Should Reach Millions More Families to Lessen Hardship, November 30, 2020, at appendix table 1, available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/cash-assistance-should-reach-millions-more-families-to-lessen

[xx] See Food and Nutrition Service, U.S. Dep’t of Agriculture, SNAP Participation Rates by State, Working Poor People, last updated August 2020, available at https://www.fns.usda.gov/usamap

[xxi] Compare Idaho Stat. 63-3029L (2021) available at https://legislature.idaho.gov/statutesrules/idstat/title63/t63ch30/sect63-3029l/, with Maryland Code Sec. 10-751 (2021) available at https://govt.westlaw.com/mdc/Document/N10B5DBA0801E11EB901A96A6365F968D?originationContext=document&transitionType=StatuteNavigator&needToInjectTerms=False&viewType=FullText&contextData=%28sc.Default%29.

[xxii] Julia B. Isaacs, Eleanor Lauderback, & Erica Greenberg, Urban Institute. Public Spending on Children in New Jersey, April 2021 at 4. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/104122/public-spending-on-children-in-new-jersey-an-analysis-from-the-urban-institutes-state-by-state-spending-on-kids-dataset_1.pdf

[xxiii] Ibid.

[xxiv] See National Conference of State Legislatures, Child Tax Credit Overview, October 19, 2021, https://www.ncsl.org/research/human-services/child-tax-credit-overview.aspx

[xxv] Ibid.

[xxvi] See Congressional Research Service, The Child Tax Credit: Temporary Expansion for 2021 Under the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA; P.L. 117-2), May 12, 2021, at p. 2-3, available at

https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN11613

[xxvii] Bridget Ansel, Having a Child Comes with Significant Financial Consequences, October 4, 2016, https://equitablegrowth.org/having-a-child-comes-with-significant-financial-consequences/.

[xxviii] See Areeba Haider, The Basic Facts about Children in Poverty, January 12, 2021 at fig. 4, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/poverty/reports/2021/01/12/494506/basic-facts-children-poverty/

[xxix] Internal Revenue Service, Child Tax Credit Update Portal, https://www.irs.gov/credits-deductions/child-tax-credit-update-portal (retrieved on November 9, 2021)

[xxx] Sophie Collyer et al., The Century Foundation, What a Child Allowance Like Canada’s Would Do for Child Poverty in America, July 21, 2020, at tbl. 1, https://tcf.org/content/report/what-a-child-allowance-like-canadas-would-do-for-child-poverty-in-america/?session=1

[xxxi] Jennifer L. Romich & Thomas Weisner, How Families View and Use the EITC: Advance Payment versus Lump Sum Delivery, 53 Nat’l Tax Journal 1245 (2000), available at https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.17310/ntj.2000.4S1.09

[xxxii] See Manoj Viswanathan, The Hidden Costs of Cliff Effects in the Internal

Revenue Code and Proposals for Change, 164 U. Penn. Law Review 931 (2016), available at

https://repository.uchastings.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2265&context=faculty_scholarship.

[xxxiii] Kids Count Data Center, Child Population by Nativity in New Jersey, updated October 2020, https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/116-child-population-by-nativity?loc=32&loct=2#ranking/2/any/true/1729/76/448

[xxxiv] Protecting Immigrant Families has provided an extensive list of eligibility for various federal programs here: https://protectingimmigrantfamilies.org/immigrant-eligibility-for-public-programs-during-covid-19/

[xxxv] Crystal Muñoz, Georgia Budget and Policy Institute, Immigrant-Inclusive Tax Credits Are More Important Than Ever, https://gbpi.org/immigrant-inclusive-tax-credits-are-more-important-than-ever/

[xxxvi] Internal Revenue Service, FAQ: Dependents, Last updated Nov. 4, 2021, https://www.irs.gov/faqs/filing-requirements-status-dependents/dependents/dependents.

[xxxvii] Internal Revenue Service, Publication 501 (2020), Dependents, Standard Deduction and Filing Information, at table 5 https://www.irs.gov/publications/p501#en_US_2020_publink1000196863.

[xxxviii] James Hawkins, Berkeley Institute for the Future of Young Americans,The Rise of Young Adult Poverty in the U.S., Issue Brief (June 2019) at p. 5, available at https://gspp.berkeley.edu/assets/uploads/page/poverty_FINAL_formatted.pdf.

[xxxix] Ibid.

[xl] See U.S. Dep’t of the Treasury, Advance Child Tax Credit Payments Disbursed October 2021, by State, October 15, 2021, available at https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/131/Advance-CTC-Payments-Disbursed-October-2021-by-State-10142021.xlsx

[xli] Legal Services New Jersey, Poverty Research Institute, True Poverty: What It Takes to Avoid Poverty and Deprivation in the Garden State, July 2021, at 20, https://proxy.lsnj.org/rcenter/GetPublicDocument/00b5ccde-9b51-48de-abe3-55dd767a685a (identifying 320 percent federal poverty level as the true cost of living for New Jersey families with children). Other estimates place the real survival budget near $88,000 for a family of four, see United Way of Northern New Jersey, ALICE in New Jersey: A Financial Hardship Study, 2020 New Jersey Report, at p. 4, available at https://www.unitedforalice.org/Attachments/AllReports/2020ALICEReport_NJ_FINAL.pdf.

[xlii] Kids Count Data Center, Children in Poverty by Age Group in New Jersey, last updated September 2020, https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/5650-children-in-poverty-by-age-group?loc=32&loct=2#detailed/2/32/false/1729,37,871,870,573,869,36,868,867,133/17,18,36/12263,12264

[xliii] See Julia B. Isaacs, Eleanor Lauderback, and Erica Greenberg, Urban Institute, Public Spending on Children in New Jersey, April 2021, at 4. Available at https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/104122/public-spending-on-children-in-new-jersey-an-analysis-from-the-urban-institutes-state-by-state-spending-on-kids-dataset_1.pdf

[xliv] For more detail on the California Young Child Tax Credit, see Alissa Anderson, California Budget & Policy Center, The CalEITC and Young Child Tax Credit: Smart Investments to Broaden Economic Security for Californians, October 2019, https://calbudgetcenter.org/resources/the-caleitc-and-young-child-tax-credit/.

[xlv] Diana Boesch, The Gender Policy Report, Federal Assistance Does Not Help Poor Mothers Pay for Diapers, May 29, 2018, https://genderpolicyreport.umn.edu/federal-assistance-does-not-help-poor-mothers-pay-for-diapers/.