To read a PDF version of this report, click here.

The best investment a state can make is in its children, yet New Jersey is falling short in one of its most effective childhood health programs, the Child Health Insurance Program (CHIP). With the help of the Affordable Care Act, New Jersey has reduced the uninsurance rate by about a third since 2013.[1] Currently, about 800,000 children receive comprehensive quality health coverage in NJFC (which consists of both Medicaid and CHIP), which represents one in three children in the state.[2] The uninsurance rate is now so low that New Jersey is in a position where it can realistically achieve a goal that would have been unheard of only a few years ago: universal health coverage for kids.

That means more healthy children and a lower cost for taxpayers by preventing costly health problems later in life. The research is clear that coverage causes a reduction in adverse health outcomes for children, such as poorer health; avoidable hospitalizations; delayed prescriptions; less access to care from a specialist; newborn complications; no regular physician; unmet prescription needs; fewer visits to the emergency room; and death.[3] The research also shows major social benefits, such as fewer school absences[4] and higher graduation rates;[5] better jobs when these kids become adults;[6] as well as less medical debt and bankruptcies for the family.[7]

Assuring affordable health coverage for all kids is a historic opportunity that must not be wasted, but to meet this laudable goal, the state needs to overcome the following challenges:

New Jersey Is Still Behind Many Other States in Insuring Children

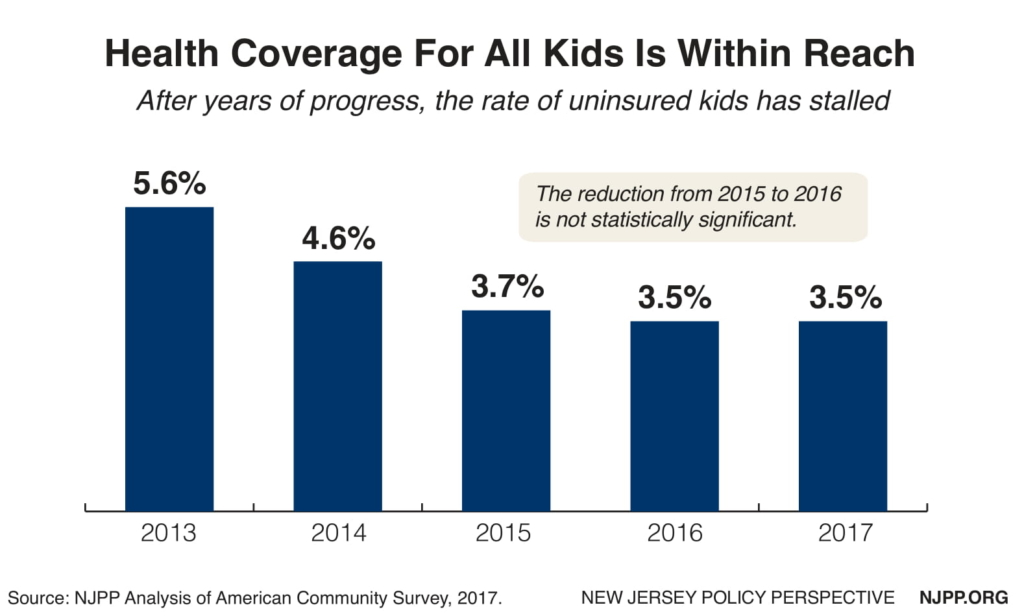

The state’s uninsurance rate dropped quickly from 2013 to 2015 (5.6 percent to 3.7 percent), but has remained flat for three years. In total, 78,000 children remain uninsured in New Jerseyand as many as 40 percent are not eligible for current programs.[8] Nineteen other states are doing better at insuring children than in New Jersey, many of which are much less wealthy, like Louisiana, Alabama, and West Virginia.[9] New Jersey’s uninsurance rate is higher than all Northeast states except Pennsylvania and Maine. Clearly NJFC has not lived up to its potential. Massachusetts and Washington, DC have essentially achieved universal health coverage for their children, so it can be done.

Federal Anti-Immigrant Policies Discourage Enrollment in NJFC

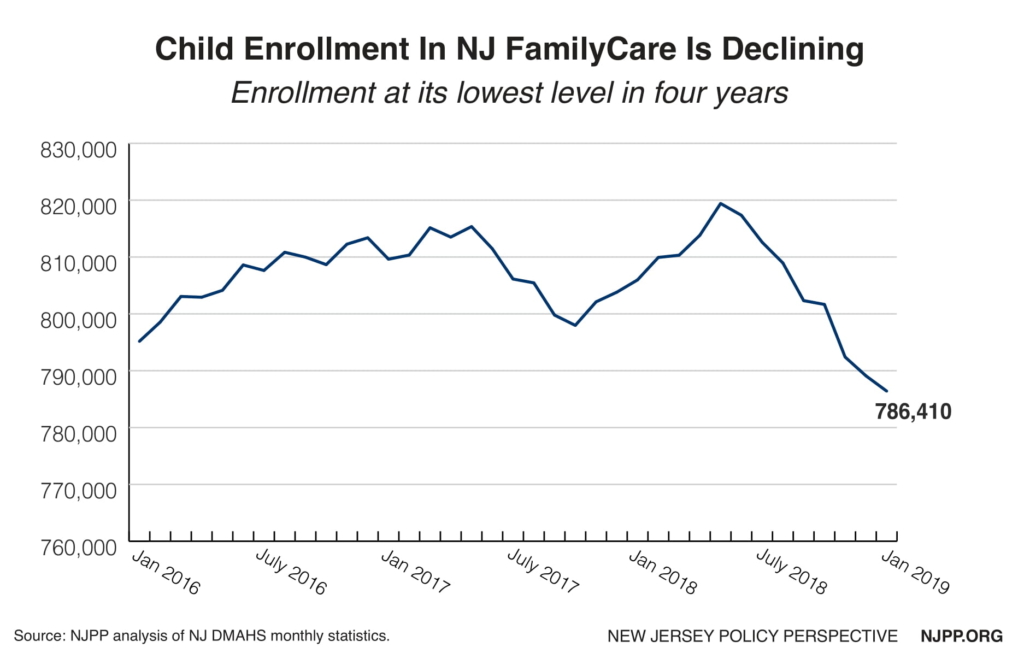

One of the main reasons that the uninsurance rate for children in New Jersey is higher than in many other states is that it has the sixth highest number of children in immigrant families in the nation and many immigrant parents are reluctant to enroll their children in any public program because of federal anti-immigrant policies. Like in many other states, for example, from May 2018 to January 2019, the enrollment of kids in NJFC declined by 33,000, resulting in the lowest enrollment in approximately four years.[10] While much of this decline may be due to the improved economy, it also probably means that fewer children are applying for assistance because of existing and proposed punitive immigration policies from the Trump administration.

Unfortunately, if enrollment trends in NJFC continue to be less than expected, the number of uninsured children will likely continue to remain flat — or actually go up. Of particular concern is the proposed “public charge” rule that could result in the denial of citizenship to legal immigrant parents if their child received Medicaid.[11] There are an estimated 150,000 citizen children in NJFC who have non-citizen parents who could be affected by the proposed public charge rule, which could result in between 22,500 to 52,500 children losing coverage.[12]

NJFC’s systemic outreach to schools is broad-based and not based on immigration status. New Jersey relies mainly on working with public schools to reach all uninsured kids, but other states have made extensive use of contracts with community-based organizations that have the trust of the Latino community to reach these families or have used evidence-based strategies, such as parent mentoring programs that employ the parent enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP to do the outreach.[13]

New Jersey Is Losing Up To $60 Million In Federal Funds for Uninsured Children Already Eligible for NJFC and the Marketplace

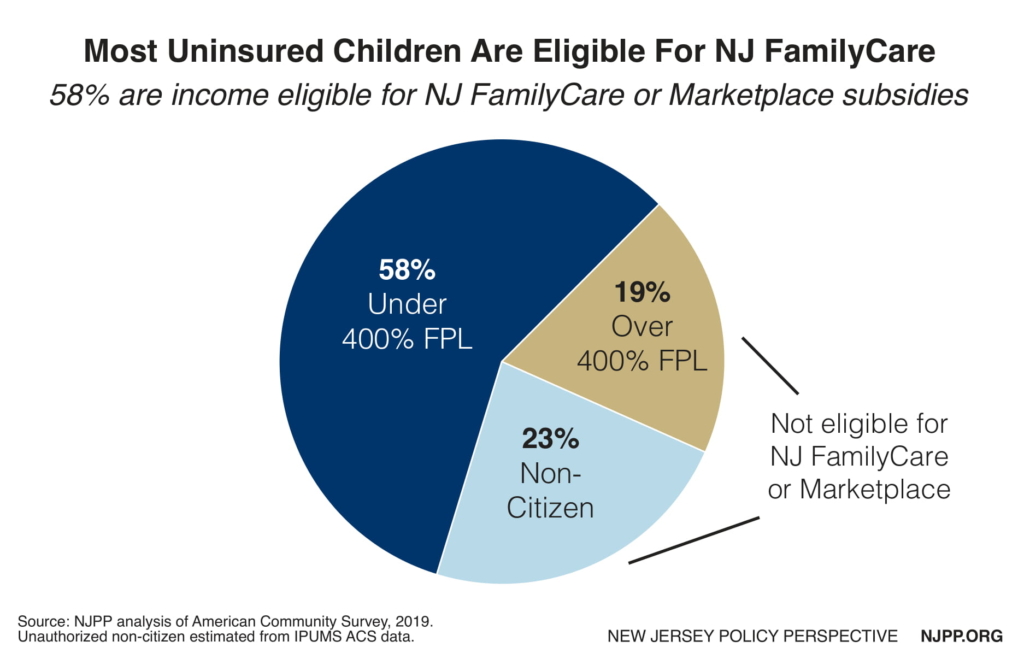

Over half (58 percent) of all uninsured children in New Jersey are eligible for, but not enrolled in NJFC — which has an income limit of 355 percent of the federal poverty level — and in the Marketplace, which has an income limit of 400 percent of the federal poverty level. That means most of them are eligible for coverage that is matched by the federal government at 50 percent in Medicaid and at least 65 percent in Child Health Insurance Program (CHIP). If New Jersey enrolled all these children, it would receive $60 million in federal matching funds.[14] Any new federal funds would increase economic activity in New Jersey because they have a multiplier effect since they come from outside the state and create new jobs.

Major Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities in Covering Children

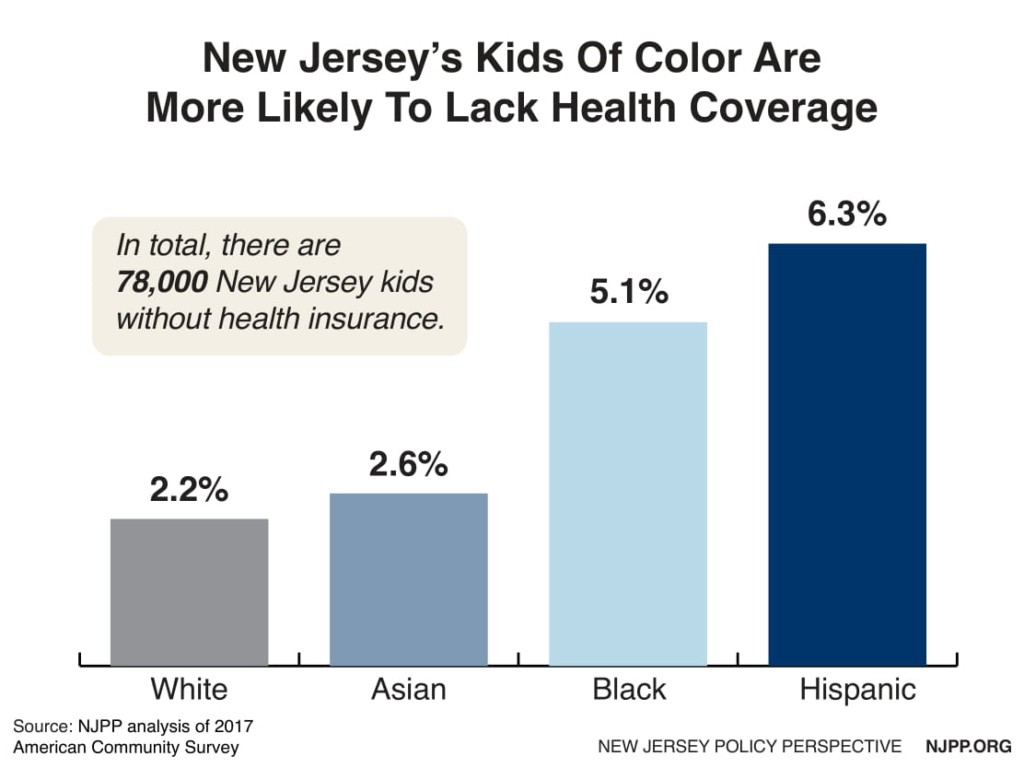

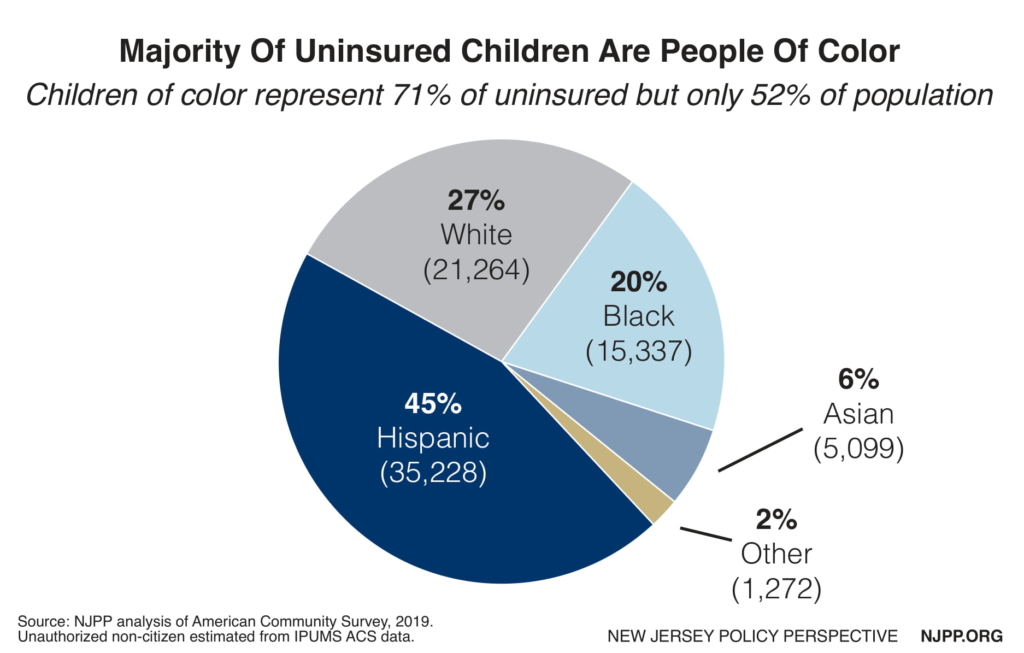

Health equity means that every child should have an equal opportunity for good health regardless of the color of their skin. Unfortunately, that is not the case in New Jersey, as indicated by the uninsurance rates of children. The uninsurance rate for White kids is 2.2 percent. The rate for Hispanic children is three times higher, at 6.3 percent, while the rate for Black children is two and a half times higher, at 5.1 percent.

This data illustrates a disturbing reality in New Jersey — one of the most affluent states in the nation — as nearly three quarters (71 percent) of all children who are uninsured are children of color. In raw numbers, that means that 35,000 Hispanic children are uninsured, as are 15,000 Black children, and 5,000 Asian children, while only 21,000 white children are uninsured. We know that these inequities not only harm people of color when they are children, but when they grow up as well. For example, Black New Jerseyans die nearly five years earlier than white New Jerseyans.

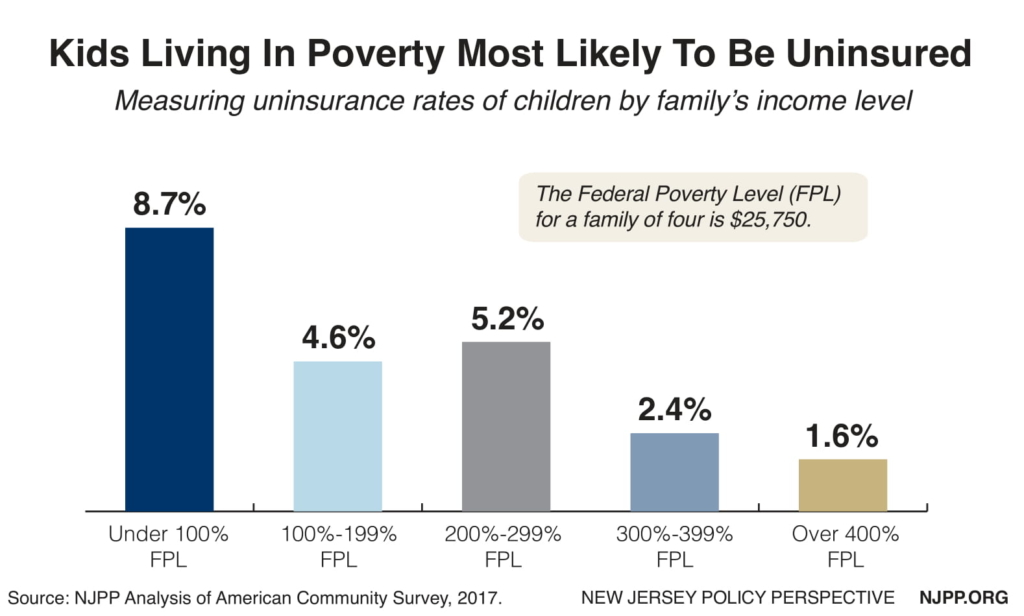

Children from Lower-Income Families Are Much More Likely to Be Uninsured Than Wealthier Kids

Wealthier children in New Jersey are more than five times more likely to be insured than poor kids. Whereas the uninsurance rate for kids above four times the poverty level is only 1.5 percent, the uninsurance rate for kids below the federal poverty level is a staggering 8.7 percent. These children meet the income level for Medicaid (138 percent of the federal poverty level) which provides comprehensive benefits and no cost sharing, although some of them may not be eligible.

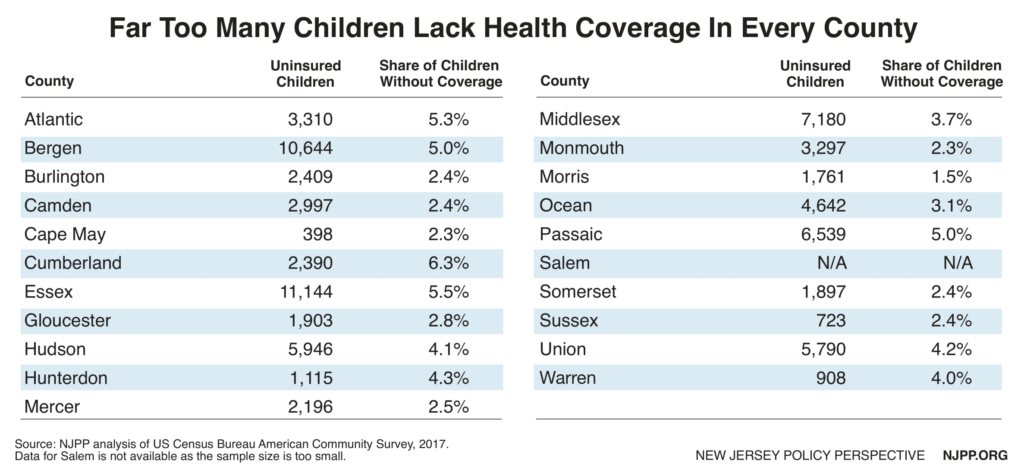

Health Coverage for Kids Often Depends on Where They Live

A child’s health should not depend on where they live, but that is often the case in New Jersey. Cumberland County has the highest uninsurance rate at 6.3 percent, which is four times greater than wealthy Morris County, which has the lowest rate at only 1.5 percent. Unlike some other states, counties in New Jersey do not provide health coverage for uninsured kids, so the only way they can obtain public coverage is through the state’s program, NJFC. The uninsurance rate for kids in Morris County is already near universal health coverage, but that is not nearly the case in other parts of the state, especially in other much less affluent counties with higher unemployment rates.

CHIP Premiums are Among the Highest in the Nation

New Jersey’s maximum premium ($152 a month) in CHIP is the second highest premium in the nation for families above 300 percent of the federal poverty level, the second highest (tied with New York at $90) above 250 percent of the poverty level, and the fourth highest ($45 a month) above 200 percent of the poverty level.[19] These high costs are especially problematic in New Jersey because the state has one of the highest costs of living in the nation, especially for housing, so these families have little left in disposable income for premiums. This policy is completely inconsistent with Medicaid in New Jersey, which does not charge any premiums. Twenty-one states do not charge any premiums.

Further, these exceptionally high costs are even worse than they appear, as New Jersey does not vary premiums by family size. For example, the maximum premium in New York for families above 300 percent of the federal poverty level is $135 a month, but for one child it is only $45. Missouri, Vermont and Washington all vary their premiums by family size.

Waiting Periods in CHIP Cause 90-Day Gaps in Coverage

Unlike 36 other states, New Jersey also requires that children must be uninsured for 90 days before they can enroll in CHIP if they leave employer-based coverage, which is the maximum allowed under federal law. The state does allow exceptions to the 90 days if they leave employer coverage through no fault of their own. Other than New Jersey, Maine is the only state in the Northeast that requires a waiting period. There is a growing recognition among states that this requirement simply creates another gap in health coverage. Within the last five years alone, at least 24 states have eliminated their waiting periods and two states moved all their children in CHIP into Medicaid, which does not require a waiting period.[20] States surrounding New Jersey that ended their waiting periods entirely are New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Connecticut, and Maryland.

Many Middle-Income Children Are Denied Coverage in CHIP

Citizen children who exceed the income eligibility level for NJFC at 355 percent of the federal poverty level and for the Marketplace at 400 percent of the federal poverty level are also denied any subsidized health coverage. There are 14,600 such children in New Jersey, which represents 19 percent of all the uninsured children. Technically they should still be eligible for CHIP because state law requires the establishment of a buy-in program that allows consumers to purchase the full cost of insurance at reduced rates. Such a program was in operation until 2010, when the Christie administration decided that they would not make the changes that were needed to make the plans compliant with the essential benefits that were required in the Affordable Care Act.

However, Congress has granted states new flexibility that will make it easier to administer a new program at lower rates. The savings to the consumer could be major with no cost to the state. The cost to insure a child in the private market is about twice the cost for coverage in CHIP.[21]

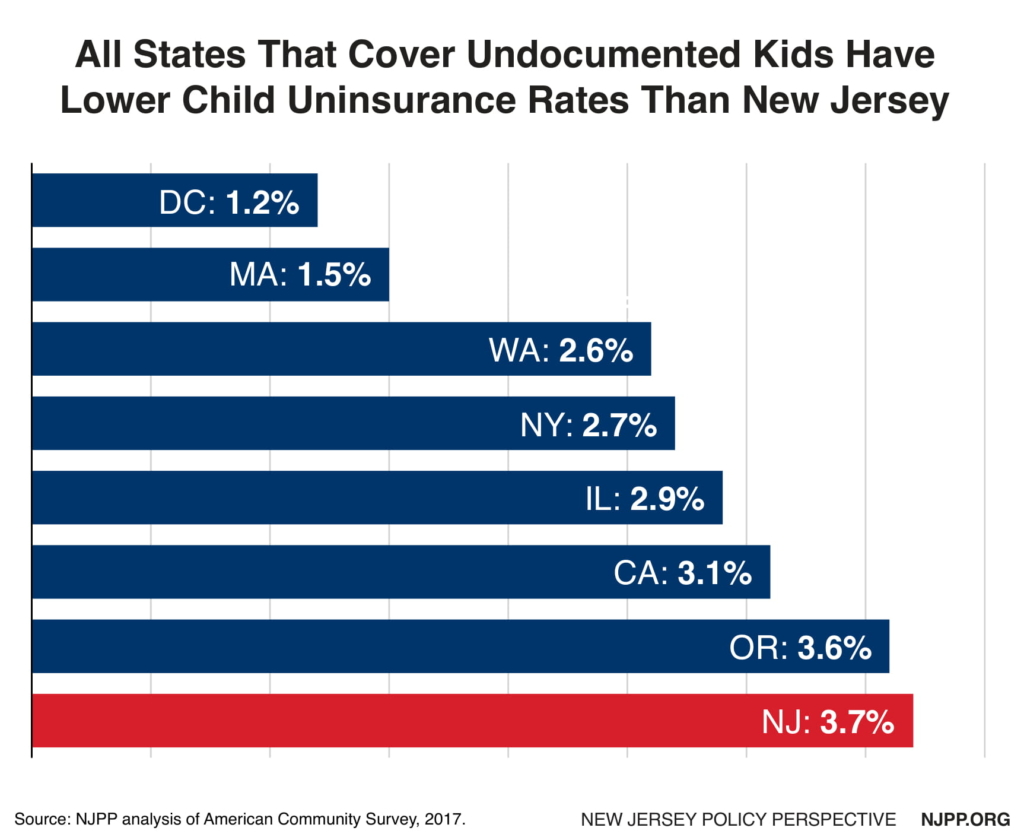

Unauthorized Immigrant Children are Ineligible for NJFC

There are about 17,000 undocumented, uninsured immigrant children in New Jersey who are also ineligible for NJFC under state law. These children represent 23 percent of all uninsured kids in the state. All six states and DC that have covered undocumented kids have lower uninsurance rates than in New Jersey. These states recognize that these children did not choose to live in this country — and they get sick just like any other kid. Ironically the state requires that they attend school and will pay for that education along with the local governments, but the state will not fund their health coverage. This investment in their education would be much more effective if these kids had health coverage as they would spend less time home sick or in school getting their classmates sick, too.

Recommendations

While these challenges are significant, there are common sense solutions that will cost little to implement yet could be a game changer in making affordable health coverage available to every child in New Jersey. Given that so many children in New Jersey are currently still without any health coverage, the steps below should be taken as soon as possible. All costs are annualized; State FY 2020 costs would be about half these estimates assuming an implementation date of January 2020 (half the fiscal year).

Develop Better Strategies to Reach More Uninsured Children

- Earmark funding for outreach on a permanent basis. This will allow the state to conduct the targeted and intensive outreach necessary to enroll the remaining uninsured. This funding would also be used to research where underserved children live.

- Focus outreach efforts on creating a permanent infrastructure of local organizations (including faith-based) that the community trusts which can effectively reach children with barriers to enrollment.

- Authorize a parent mentoring program which has been shown to be more effective than traditional methods to insure Latino kids, improve health outcomes and increase employment for parents.

- Authorize funding for community-based demonstration projects, in cooperation with public health agencies, schools and other local entities, to test various ways to provide health care for children of color and immigrant children who are unlikely to enroll in NJFC.

State Cost: $1 million for outreach, which could obtain up to another $1 million in federal matching funds and $1 million for demonstration projects, which may be eligible for federal funding depending on how they are structured.

Remove Major Administrative Barriers to Health Coverage

- Consistent with Medicaid and all other families below 200 percent of the federal poverty level in CHIP, eliminate all premiums to other families in CHIP.

- Like 36 other states, do not require that a child wholeaves employer-based healthcoveragemust be uninsured for 90 days before enrolling in CHIP.

State Cost: Eliminating premiums would result in lost collections of up to $28 million annually in CHIP which would be offset set by $22 million in federal matching funds resulting in a state cost of $6 million (this would rise to $10 million in the future as the federal CHIP matching rate gradually decreases to 65 percent). This does not take into account substantial administrative savings that would be achieved and that some of those collections would continue for co-payments which would not be eliminated. Ending the 90-day waiting period would increase enrollment by about 1,500 and cost about $900,000 in state funds which would be matched with $2.9 million in federal funds based on the experience of many states that have abandoned the waiting period.[22] This change would likely create administrative savings.

Cover Those Children Who Are Currently Ineligible For NJFC

- Reinstate and improve the buy-in program for families above 400% of the federal poverty level as long as they do not have coverage availabletothem for less than 9.5 percent of the family income similar to ACA policy,with the goal of making it as seamless and cost-effective as possible and open to more than one insurer.

- Authorize the state to require any or all the carriers to participate in the buy-in program as a condition for continuing to participate in NJFC.

- Repeal any eligibility restrictions in NJFC based on immigration status.

- Strengthen the rules for confidentiality to apply to all information relating to the administration of CHIP and Medicaid and allowing the state to withhold information from the federal government on children who receive health coverage at all state cost and where such sharing of information may not be in the best interest of the child.

State Cost: There is no cost for the buy-in because the parents would pay the full cost in their premiums and any administrative costs or costs associated with any possible adverse selection. It would cost about $10 million to make uninsured unauthorized children eligible assuming a 25 percent participation rate which does not consider reduced costs from a decrease in the spread of infectious diseases in schools in addition to other health and social savings outline earlier. Further, the federal government would still be responsible for paying the full cost for hospitalization which could reduce the above estimate significantly.

Improve Transparency and Accountability

- Require that the work group, authorized under state law that advises the Department of Human Services on ways to improve outreach, meet at least annually.

- Require the Department to submit an annual report to the legislature on actions it has taken and their results to provide affordable quality health coverage for all children in New Jersey and the extent to which coverage disparities have improved based on income, race/ethnicity, and geography.

State Cost: Insignificant administrative costs.

Possible Revenues

The $19 million total annual cost for all these recommendations ($9.5 million in SFY 2020 assuming a January 2020 start date) is statistically insignificant compared to a $15 billion budget for NJFC (the state cannot even project total NJFC cost from one year to the next within this level of accuracy). Thus, they should be funded with general revenues.

However, if additional revenues need to be identified for this expansion, it is likely that the savings which will occur as a result of the sharp drop in the child enrollment in NJFC due to existing and proposed federal anti-immigrant policies and a better economy could be more than sufficient to fund this proposal as would part of the revenues that would be generated by the Corporate Responsibility Fee proposed by Governor Murphy, which is based on the number of employees (and their dependents) who are enrolled in Medicaid at all public cost, or other similar fee.[23]

End Notes

[1]American Community Survey, 2017

[2] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Medicaid Works: A State by State Look, no date, https://www.cbpp.org/medicaid-works-a-state-by-state-look#New_Jersey.

[3] Flores G. Lesley B, Children and US Federal Policy on Health and Health Care: Seen But Not Heard. JAMA 2005;168(12):1155-63. Pediatric.

[4] Howell Trenholm, et al, The Impact of New Health Insurance Coverage on Undocumented And Other Low-Income Children: Lesson From Three California Counties. Journal of Health Care for The Poor and Underserved, 2010.

[5] Cohodes, S, et al, The Effect of Child Health Insurance Access on Schooling: Evidence from Public Insurance Expansion. The National Bureau of Economic Research, 2014.

[6] D. Brown, et al, Medicaid As an Investment In Children: What Is The Long-Term Impact On Health Receipts? National Bureau of Economic Research, January 2015.

[7] M. H. Boudreaux, et al, The Long-Term Impact of Medicaid Exposure in Early Childhood: Evidence From The Program Origin, Journal of Health Economics, January 2016.

[8] American Community Survey, 2017.

[9]Joan Alker, Olivia Pham, Nation’s Progress on Children’s Health Coverage Reverses Course, November 21, 2018, https://ccf.georgetown.edu/2018/11/21/nations-progress-on-childrens-health-coverage-reverses-course/

[10] DHAHS, NJFC Enrollment Statistics, http://www.njfamilycare.org/default.aspx

[11]Georgetown University Health Policy Institute, How Proposed Changes to Public Charge What Impact Children In Immigrant Communities, no date, https://ccf.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Public-Charge-Fact-Sheet_Final_11918.pdf

[12] Samantha Artiga, Effects of Public Charge Changes on Health Coverage for Citizen Children, KFF, May 2018, http://files.kff.org/attachment/Issue-Brief-Potential-Effects-of-Public-Charge-Changes-on-Health-Coverage-for-Citizen-Children

[13] Glen Flores, et al, Parent Mentoring Program Increases Coverage Rates for Uninsured Latino Children, Health Equity, March 2018.

[14] The average total cost in CHIP and Medicaid for a child is $2,400 which was multiplied times the number of kids who are eligible for NJFC (minus unauthorized immigrant kids). Federal matching is based on 50 percent federal funds in Medicaid and 65 percent in CHIP which was prorated base on eligible kids for each of these programs.

[15] DHAHS, NJFC Enrollment Statistics, http://www.njfamilycare.org/default.aspx

[16] Georgetown University Health Policy Institute, How Proposed Changes to Public Charge What Impact Children In Immigrant Communities, no date, https://ccf.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Public-Charge-Fact-Sheet_Final_11918.pdf

[17] Samantha Artiga, Effects of Public Charge Changes on Health Coverage for Citizen Children, KFF, May 2018, http://files.kff.org/attachment/Issue-Brief-Potential-Effects-of-Public-Charge-Changes-on-Health-Coverage-for-Citizen-Children

[18] Glen Flores, et al, Parent Mentoring Program Increases Coverage Rates for Uninsured Latino Children, Health Equity, March 2018.

[19] Trisha Brooks, Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid And CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, Renewal, And Cost Sharing Policies As of January 2019: Findings from a 50-state Survey, March 2018 http://files.kff.org/attachment/Report-Medicaid-and-CHIP-Eligibility-Enrollment-Renewal-and-Cost-Sharing-Policies-as-of-January-2019

[20] Ibid.

[21] Healthcare.gov

[22] The enrollment changes for all states that ended their waiting period in 2014 was calculated for 2013 and 2015 and compared to all other states. The enrollment changes for states that dropped their waiting period was a .2 percent increase vs. a .5 percent decrease in all other states. That .7 percent difference was applied to the CHIP enrollment and costs in the governor’s 2020 budget. The sources for enrollment rates for all states are https://ccf.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Getting-Into-Gear-for-2014.pdfand https://ccf.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Modern-Era-Medicaid-January-2015.pdf

[23] FY2020 Budget in Brief, p. 6,https://www.nj.gov/treasury/omb/publications/20bib/BIB.pdf