Investments in early care and education plus stronger labor standards would have tremendous payoff

To read a PDF version of this report, click here.

For the over 400,000 New Jersey mothers with children under the age of 6, balancing child care and career can be a daunting task due to the lack of adequate child care assistance – a task doubly difficult for lower-income moms. This barrier harms New Jersey’s economic growth and state revenues, in addition to the development of children.

The state’s early care and education programs help mothers with young kids earn $1.2 billion in wages and generate over $60 million in property and income taxes annually. However, the impacts of universal, high quality preschool would be far greater. In addition to the long-term economic benefits of investing in children, universal preschool would result in upwards of 10,000 more mothers entering the New Jersey workforce. In total, universal preschool would help about 200,000 mothers earn $7.5 billion and contribute $400 million in taxes each year.

A third of New Jersey’s mothers with young children – or about 130,000 – are living at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty level, or about $48,600 a year for a family of four. These poor and low-income mothers have limited access to public high-quality early care and education programs that could help them work and give their children a brighter future – in fact, we estimate that state and federally funded early care and education programs only reach about 60 percent of them.[1]

In addition, over 40 percent of New Jersey’s working mothers with young children are in service-sector jobs. Many of these occupations, particularly those in retail and food service, come with non-standard hours, unpredictable schedules and low wages. These factors increase financial and child care-arrangement stress, undermining working families’ ability to get ahead.

In short, New Jersey’s working mothers of young children face many barriers to balancing work and parenting, with poor and low-income mothers struggling the most. To solve this complex set of problems, a comprehensive policy response – anchored in increased investments in early care and education, and stronger labor standards – is necessary.

Specifically, state lawmakers should:

- Increase preschool aid and call on the federal government to invest further in state preschool programs, with the ultimate goal of universal preschool in New Jersey.

- Increase the income eligibility for wraparound care in school districts that currently have state-funded preschool.

- Piggyback on federal tax credits that help families with the cost of raising children and paying for care.

- Call on the federal government to protect Head Start and the Child Care and Development Fund.

- Mandate that employers provide workers with predictable and stable work schedules.

- Increase the state minimum wage to a more livable wage.

- Ensure that women workers have better tools to fight pay discrimination.

- Allow all workers to take paid time off of work when they or a loved one is sick.

Working Families Need Dependable, Affordable Child Care to Succeed

Dependable child care is crucial for working mothers and their families. However, the cost of child care in New Jersey is extremely high – between $8,000 and $11,000, on average, per year, depending on the age of the child and whether it’s center or home-based care.[2] Since this cost is clearly out of reach for low-income families, a variety of state and federal means-tested programs offer assistance (these programs are detailed in the fourth section of this report).

To give children the best opportunity for lifelong success, the care should be high-quality and education driven. Children who attend high-quality preschool are less likely to be held back or placed in special education, and more likely to graduate and pursue further schooling.[3] This, in turn, has enormous economic benefits for society as a whole. For every dollar invested in high-quality preschool, the return is estimated to be between $3 and $18.[4]

Public programs for early care and education also boost women’s workforce participation, which is key to sustaining our nation’s economic growth.[5] Mothers essentially “propped up” the nation’s labor force participation rate for many decades, but their rates have stagnated since the 1990s.[6] Economists worry that a significant factor is the struggle to balance work and family responsibilities; most mothers work full time as breadwinners and co-breadwinners, yet they still do the bulk of housework and family caregiving.[7],[8]

The child care sector is also a critical building block for economic development. It supports and sustains our workforce of caregivers and provides immediate and long-term benefits to New Jersey’s economy. The last comprehensive analysis of the New Jersey child care industry found it was a $2.6 billion industry directly supporting approximately 65,300 full-time equivalent jobs.[9]

New Jersey’s Working Mothers with Young Children: Who Are They, Where Do They Work and How Much Do They Earn?

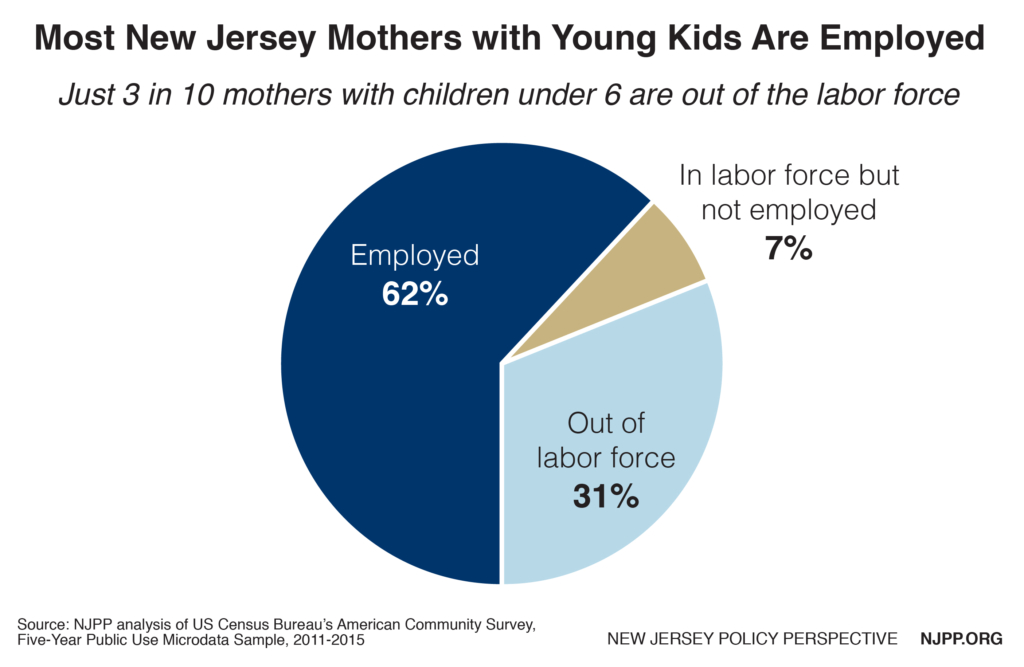

Most New Jersey mothers with young children are in the labor force (69 percent) and have immediate or near-term child care needs to help ensure that they can work. Of the 413,000 New Jersey mothers with at least one child under the age of 6, 254,000 are working – and another 29,700 are in the labor force but not currently employed, meaning they could be taking family or sick leave or looking for a job.[10]

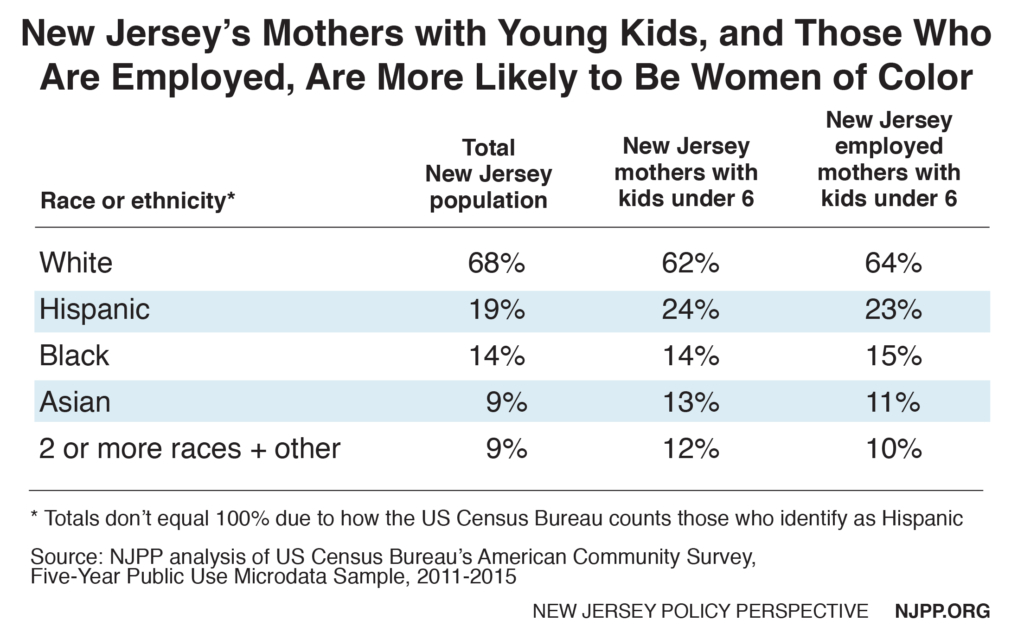

Compared to the entire population of New Jersey, mothers of young children are more likely to be women of color or to identify themselves as Hispanic in the American Community Survey.

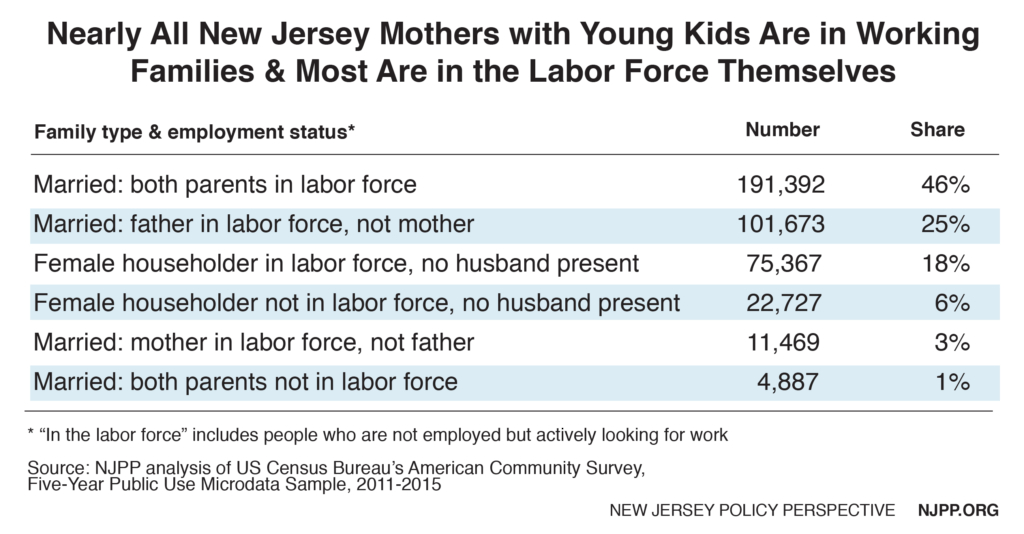

These working mothers are increasingly responsible for the economic security of their families as breadwinners or co-breadwinners. Most New Jersey mothers with young children are in families that consist of married parents who are both in the labor force. About one in four are heading their households with no husband present; of these the overwhelming majority of mothers are working. Less than 5 percent of unmarried working mothers with young children have any male partner in the household, and less than one-third of New Jersey’s female-headed households receive child support.[11],[12]

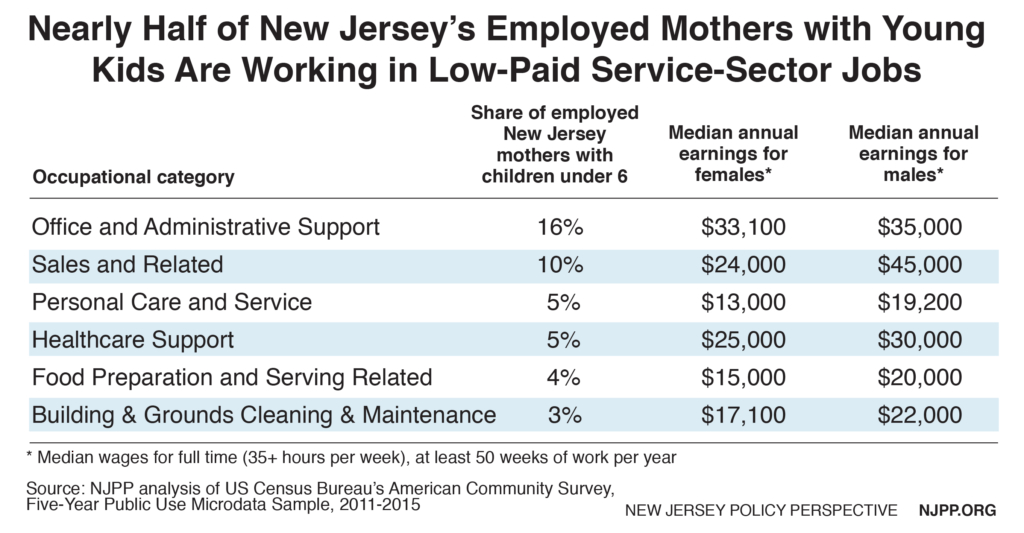

A large number of these working mothers – 44 percent – are in service-sector occupations, which include many of the lowest paying jobs in New Jersey. Across these occupations, the median full-time year-round wages are lower for women than men, an indicator of the persistent pay gap that exists between men and women, and it is even greater for women of color. In New Jersey, Latinas make 43 cents for every dollar paid to their white, non-Hispanic male counterparts; Black women make 58 cents, white women make 74 cents, and Asian women make 87 cents.[13]

Mothers with children under 6 are much more likely than the general population to work in healthcare support and personal care and service. Top occupations in these categories include hairdressers, cosmetologists, child care workers, home health aides, and medical assistants.

In addition to low pay, many of these jobs, particularly in retail and the food industry, are more likely to feature erratic scheduling, as well as non-standard and involuntary part-time hours. Irregular scheduling practices that are the hallmark of service-sector jobs – like different hours in any given week, short notice of schedule and last-minute schedule changes – make it nearly impossible to arrange for child care, and pay for it too, since variations in hours mean unpredictable income.[14]

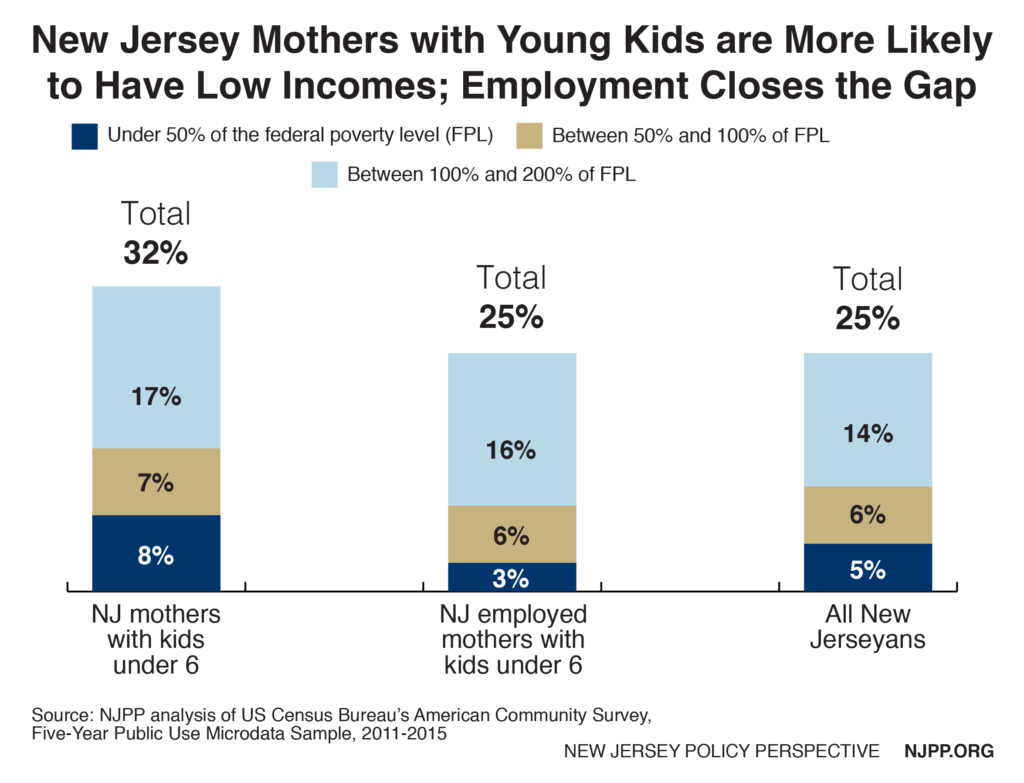

Mothers with children under 6 are also more likely than other New Jerseyans to have low incomes. Over 130,000 mothers with young children, or 32 percent, are living below 200 percent of the federal poverty level, or $48,600 for a family of four.[15] Of these, nearly half are very poor, living below $24,300 for a family of four, or 100 percent of the federal poverty level. Over 31,000 New Jersey mothers with young children live in deep poverty, below 50 percent of the federal poverty level, which translates to $12,150 for a family of four.

Of these poor and low-income New Jersey mothers of young children, about 62,500 are working – that equals one in four of all working mothers with kids under 6 years of age who need care for their children so they can remain employed. These mothers qualify for New Jersey Cares for Kids, the state’s federally-funded child care subsidy program. But the program reaches only a fraction of those mothers – roughly 14,000 a month.

The need for child care subsidies is even deeper, since New Jersey Cares for Kids only serves families under 200 percent of the federal poverty level – even though it obviously takes more than that to get by in high-cost New Jersey. The Economic Policy Institute’s average New Jersey family budget for a family of four, for example, is $78,300, or 322 percent of the federal poverty level.[16] This means another 16 percent of working mothers of young children, or about 40,000, struggle to get by in New Jersey, but are ineligible for child care assistance.

New Jersey’s Early Care and Education Programs: What Are They, Who Pays for Them and Who Do They Reach?

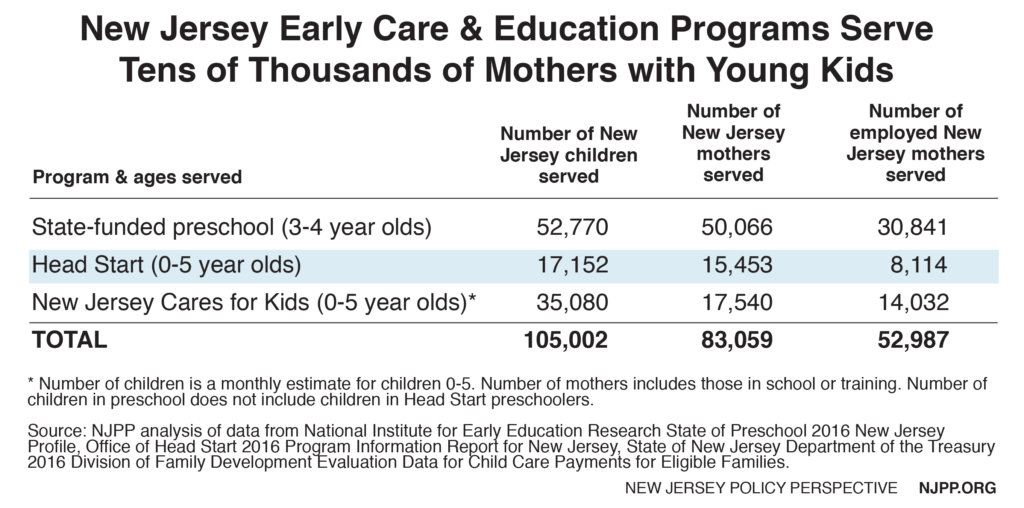

There are three main ways that New Jersey families can receive state and federal assistance with early care and education needs: New Jersey Cares for Kids, Head Start, and state-funded preschool programs. In all, these programs serve about 53,000 employed mothers with children up to the age of 5. While many families use child care programs that are subsidized by nonprofit organizations or religious institutions, there are no readily available data on the number being served by these.

State-Funded Preschool Programs

New Jersey’s state-funded preschools educated almost 53,000 children in 2016.[17] The original and largest program enrolled almost 44,000 children in school districts that were formerly known as “Abbott” districts.[18] The former Early Childhood Program Aid districts enrolled almost 9,000, while the former Early Launch to Learning Initiative districts enrolled around 600 children. All told, New Jersey spent nearly $656 million on these preschool programs in 2016.[19]

The School Funding Reform Act of 2008 mandated high-quality, full-day preschool for all low- income children in New Jersey. There are 93 “universal” school districts that meet certain socioeconomic criteria that were directed to provide preschool to all 3- and 4-year-olds, while 325 “targeted” school districts were directed to provide preschool to low-income 3- and 4-year-olds.[20] However, state lawmakers have not yet followed the funding formula, leaving about 30,000 eligible New Jersey children without free preschool each year since 2009.[21]

Evidence has overwhelmingly shown that there are substantial educational benefits for children who attend high-quality preschool.[22] They are less likely to be held back or placed in special education, and they graduate high school and attend college or other post-secondary institutions at greater rates.[23] Society as a whole benefits as well, because children who attend are less likely to engage in criminal activity or participate in welfare programs and more likely to be active in the workforce. In all, high-quality preschool results in reduced costs in education, social services and criminal justice and increased tax revenue. Economists estimate that the return on investment for preschool is between $3 and $18 for every dollar invested.[24]

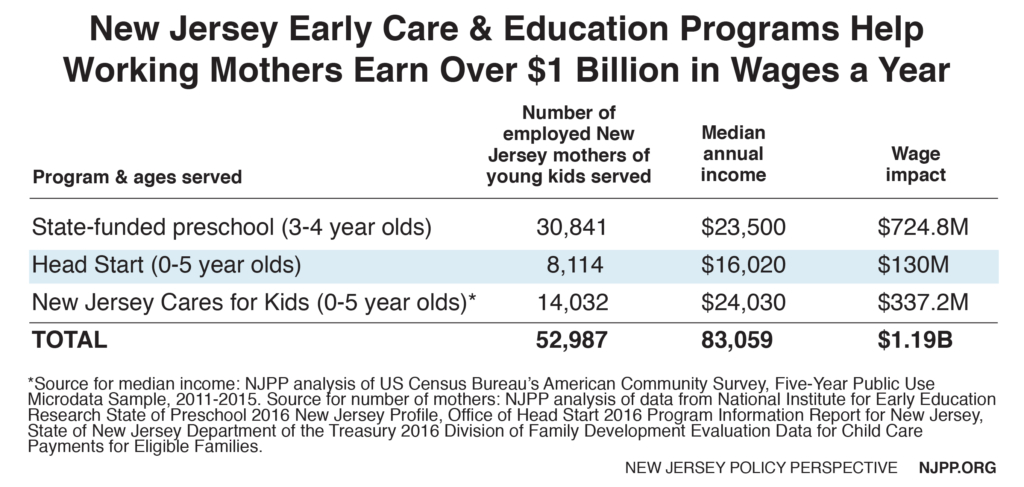

State-funded preschools in New Jersey give an estimated 50,000 mothers of young children access to high-quality early care and education, and help an estimated 31,000 of these to work and provide for their families. While there is no data on the number of these mothers furthering their education, there are likely a number who are able to attend school thanks to the availability of state-funded preschool for their children.

Free wraparound care before and after regular school hours was once provided to families enrolled in state preschools. In 2011, income limits and work requirements were established, and families had to begin applying through the New Jersey Cares for Kids program for a subsidy. The number of New Jersey children receiving wraparound care has plummeted by an astonishing 87 percent over the past decade, dropping to 3,956 in 2016 from 31,515 in 2006.[25]

High-quality preschool is expensive, so funding it will prove to be challenging. While universal preschool would benefit all children and create the greatest economic returns, focusing on preschool for the children who need it most to start is sensible.

Head Start

Head Start is a federally-funded program that provides grants primarily to local non-profit organizations that prepare low-income children under the age of 5 for school through education, health and social services.[26] An $8.2 billion program, Head Start reaches 900,000 children nationwide.[27]

Head Start is only open to families at or below 100 percent of the federal poverty level, i.e. $24,300 for a family of four.[28] New Jersey has 52 Head Start programs that served 17,152 children in 2016 – 25 programs serve 3-5 year olds, 26 serve 0-2 year olds and one serves the children of agricultural workers.[29] Some programs may contract with school districts to provide state-funded preschool. In 2016, New Jersey Head Start programs received just under $157 million in federal funds.[30]

Head Start helps about 15,500 poor New Jersey mothers access education, health and social services for their young children.[31] About 8,000 of these mothers work while their children receive early care and education opportunities from Head Start.[32]

Only 8 percent of New Jersey children in poverty ages 0-5 that qualify for Head Start were enrolled in 2016; 17 percent of qualifying 3-year-olds and 18 percent of 4-year-olds were enrolled.[33] According to estimates from the National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER), Head Start needs an additional $12 billion in annual federal funding to provide high-quality services to all eligible children.[34]

New Jersey Cares for Kids

New Jersey Cares for Kids, which provides child care subsidies to low-income families, is funded by a federal block grant known as the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) and administered by the state Division of Family Development and 14 county-level Child Care Resource and Referral agencies. New Jersey spent a total of $285 million on subsidies in 2016 – the bulk of which was paid for by the federal government.[35] Of that, $121 million consisted of federal dollars and $72 million was required maintenance of effort and matching funds from the state.[36] Another $85 million came from TANF (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families) transfers and direct TANF spending, which is an allowable use of those federal funds.[37]

To qualify for a subsidy, the parent or parents must be working or in school and the family income must be below 200 percent of the federal poverty level (roughly $48,600 for a family of four). Families in between 100 and 200 percent of the federal poverty level must make a co-pay that varies depending on family size and income. Children whose parents get cash assistance through WorkFirst New Jersey (the name for TANF in New Jersey) automatically qualify. Parents can continue receiving assistance for up to 90 days if they lose their job, but those who are job searching or unemployed aren’t eligible to apply.[38]

These subsidies help a total of nearly 100,000 New Jersey children a year, and an average of 50,000 each month; the difference is due to families moving in and out of the program.[39],[40] About 64 percent of the children are under 6 years old and the rest are between 6 and 13.[41]

In 2015, child care subsidies flowed to about 5,300 New Jersey providers, including accredited child care centers and home-based providers.[42] Subsidy amounts vary based on the child’s age and type of provider; 2014’s maximum subsidies were about $8,800 (for infant to 2.5 year olds) and $7,200 (for 2.5 to 5 years olds) for one year (N.J. Department of Human Services, 2014). The state allocated $15 million in funds to increase rates by 1 to 4 percent in 2018; in addition, the roughly 880 child care centers that participate in the state’s quality rating program will see an increase of 4 to 24 percent in their rates.[43]

Each month, New Jersey Cares for Kids helps about 14,000 mothers of young children to work and further their education.[44] According to the estimates presented here, these subsidies only reach about 22 percent of New Jersey’s 62,500 working mothers with children under the age of 6 who qualify. It’s likely that a range of factors contribute to this, including the fact that the Child Care and Development Fund is at its lowest funding level since 2002.[45] The Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP) ranks New Jersey 17th for percent of eligible children served, tying with Tennessee, South Dakota, Oklahoma, North Dakota, Nebraska and Kentucky.[46] In New Jersey, 27 percent of eligible Black children and 12 percent of eligible Latino/Hispanic children were served in 2015.[47]

Furthermore, the child care subsidy falls below the market rate for care in all New Jersey counties, forcing many families to choose providers based on cost, not quality.[48] And in high-cost New Jersey, many families who are phased out of the subsidy program experience what is called a “cliff effect.”[49] When their incomes rise over 200 percent of the federal poverty level, they can continue to receive assistance for up to a year if their income remains below 250 percent of the federal poverty level.[50] But once their income goes over 250 percent, they lose the benefit, dropping off the proverbial cliff. Even at this slightly higher income level, many families are unlikely to make enough to be self-sufficient, but they no longer receive any assistance.

A final issue of concern is that although children of undocumented immigrant parents have the right to child care subsidies, New Jersey’s eligibility forms state that additional proof of citizenship may be required.[51] This, along with the fear of deportation and separation from their children, is almost certain to prevent many qualifying parents from getting the child care assistance that they need.

Investments in Early Care & Education Would Boost the Economic Security of New Jersey’s Working Mothers with Young Children and State Revenues

Early care and education has a substantial payoff over the long run due to the investment in children – but its support for working mothers also brings immediate benefits to the state. In addition, studies have shown that free preschool increases the maternal labor supply. In other words, if New Jersey expands state-funded preschool, we can expect to see the employment rate of mothers of young children increase over time.

Of course, there are many more benefits that are worth considering. For example, employers will have workers with more reliable care who can be more productive knowing their children are in safe, enriching environments. Mothers are also not just likely to work; a portion will be able to further their education due to access to early care and education. Others may have the freedom to donate their nonworking time to community, school, and nonprofit causes.

Currently, over 50,000 New Jersey mothers are able to earn almost $1.2 billion in wages a year and contribute to the economy due to our state-funded preschool, Head Start, and New Jersey Cares for Kids. These mothers contribute an estimated $64 million in state income ($37 million) and local property taxes ($27.2 million) each year.

If New Jersey were to expand preschool as mandated by the 2008 School Funding Reform Act, an additional 22,800 working mothers of low-income children would be able to benefit from fully subsidized care for their 3- and 4-year-olds. This group of preschool expansion mothers would have a total wage impact of $480 million and generate $26 million in income and property taxes. Within this group, an estimated 1,400 would be new to the workforce as a result of preschool expansion. Assuming they are able to find employment and their wages are not impacted by their addition to the workforce, these mothers would earn an estimated $30 million and add $1.6 million in tax revenue to state and local coffers.[52]

Not surprisingly, economic and fiscal benefits of universal preschool in New Jersey would be much greater, since mothers with higher income levels would utilize universal preschool, which would be available to all mothers with young children.

Universal preschool for 3- and 4-year-olds could result in an additional 10,000 women entering the workforce over time.[53] Assuming once again that these mothers are able to find employment, and that wages are not impacted, these mothers would bring their roughly $372 million in earnings into the economy and boost income and property tax contributions by $20 million a year.

While there will likely always be a portion of families who choose private preschools, it’s reasonable to assume universal preschool in New Jersey would eventually reach most working mothers. Florida and Oklahoma, which have universal preschool, have reached 76 and 74 percent enrollment rates for children, respectively.[54] If 75 percent of New Jersey’s working mothers were able to use state-funded preschools, this would mean roughly 200,000 mothers benefitting from the program, with a wage impact of $7.5 billion. In total, these mothers would generate over $400 million in property and income taxes.

Although calculating all the benefits of expanding early care and education through preschool is beyond the scope of this report, it’s worthwhile to present a rough estimate of the costs. According to NIEER, the high-quality preschool provided in New Jersey costs $12,424 per student. There are about 200,000 3- and 4-year olds in New Jersey. If New Jersey could reach 75 percent enrollment this would mean preschool for 150,000 children, with a cost of roughly $1.8 billion.

A Policy Agenda for Working Mothers and Families

New Jersey’s working mothers of young children face a variety of challenges that make balancing work and parenting extremely difficult, with poor and low-income mothers struggling the most. Even if all mothers had access to affordable, high quality child care, a large portion would still be living in poverty, or on the edge of poverty, and would face unfair scheduling practices imposed on them by service sector employers. To solve this complex set of problems, a comprehensive policy response is necessary.

Early Care and Education

* New Jersey lawmakers should increase preschool aid, and call on the federal government to invest further in state preschool programs, with the ultimate goal of funding universal preschool. It is critical that the resources provided are sufficient to ensure high-quality programs; early care and education experts caution against settling for lower-quality programs in order to serve more children, and high-quality preschool has the largest benefits for society.

* Wraparound care in state-funded preschool districts is crucial for working families, but since 2011, income limits and strict work requirements have been in place. Lawmakers should consider increasing the eligibility for wraparound care to 250 percent of the federal poverty level and ensuring that mothers who work part time can access the wraparound care. Many mothers who work in retail and food service are involuntary part-time workers and they should not be punished for this workplace practice.

* New Jersey lawmakers should call on the federal government to protect Head Start and the Child Care and Development Fund, and to increase funding so that these programs can provide families in need with quality, affordable early care and education.

* There are many families who don’t qualify for child care assistance yet struggle to make ends meet in high-cost New Jersey. The state can piggyback on federal tax credits that help families with the cost of raising children and paying for care. A state Child Tax Credit would reach more low-income families, and benefit those with a stay-at-home caregiver. A state Child and Dependent Care credit would provide relief to working parents who pay out of pocket for child care. In 2015, over 223,000 New Jersey tax filers received this federal credit; the best way to target it to low- and middle-income families is to make the credit the most generous for the lowest earners, phase down the value as income goes up, and cap it at a reasonable income level.

Supportive Work-Family Policies

* Mothers with service sector jobs need predictable and stable work schedules. Fair scheduling policies – like ensuring advance notice of schedules, giving employees a say in their schedules, limiting on-call scheduling and more – can help put an end to workplace practices that make it harder for low-paid New Jerseyans to balance work and care.[55] The state should follow the lead of Oregon and cities like Seattle, San Francisco and San Jose and pass comprehensive fair scheduling legislation.

* The number of New Jersey mothers with young children living in poverty, or near poverty, is alarming. As breadwinners and co-breadwinners, these mothers are responsible for the economic security of their families, and they need living wages. New Jersey can support these families by enacting a statewide $15 minimum wage.

* All women deserve equal pay for equal work. Pay disparities – rooted in occupational sex segregation, discrimination and the “mommy penalty” – exist across occupations regardless of education or skill level. The state should pass the New Jersey Equal Pay Act, which was vetoed in 2016 by Gov. Chris Christie, to give women better legal tools to fight pay discrimination.

* Parents must be able to take time off when they or their children are sick. While most New Jersey workers have access to this benefit, many low-paid workers do not, adding yet another burden to the difficulty in managing care giving and jobs. Several New Jersey municipalities have passed earned sick day policies; New Jersey should enact a strong statewide policy to support working families.

Appendix: Methodology & Acknowledgments

This report used American Community Survey data and program data to examine New Jersey’s working mothers of young children and evaluate the extent to which state and federal early care and education programs provide assistance to them. Data on the number of working mothers of young children, their demographics, occupations, and incomes were generated from the American Community Survey (ACS) Public Use Microdata Samples Five-Year Estimates of 2011-2015.

For each program under consideration – state-funded preschool, New Jersey Cares for Kids, and Head Start – program data were analyzed to estimate the number of mothers of young children receiving assistance. The National Institute for Early Education Research enrollment data on preschool and the Education Law Center’s data on preschool expansion were used to estimate the number of mothers benefiting. Data on child care subsidies from the New Jersey Cares for Kids program were gathered from the New Jersey state budget. A Program Information Report for New Jersey Head Start programs was accessed to gather data on this federal program.

Wage impacts for New Jersey mothers of young children who currently use state and federal child care programs, and those who would benefit from preschool expansion and universal preschool, were generated using income data from the ACS. Finally, an estimate of the income and property tax revenue generated from these same groups was estimated by using effective tax rate estimates from the New Jersey Statistics of Income and the Rutgers Center for Government Services NJ Data Book.

A more detailed methodology with PUMS variables and all calculations is available upon request. Contact info@njpp.org for a copy.

Thank you to Professor Henry Coleman and Professor Michael Lahr for their expert guidance. Thank you to the following individuals who generously shared their time and knowledge with me as I researched early care and education in New Jersey: W. Steven Barnett, Ana Berdecia, Adriana Birne, Kathy Burke, Lorraine Cooke, Ellen Frede, George Kobil, Cynthia Rice and Alana Vega.

Endnotes

[1] In this report “low-income” is defined as living at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty level, while “poor” is defined as living at or below 100 percent of the federal poverty level.

[2] New Jersey Association of Child Care Resource and Referral Agencies (2013). The High Price of Child Care 2013: A Study on the Cost of Care in New Jersey. Retrieved from www.childcareconnection-nj.org.

[3] Friedman, A., Frede, E., et al (2009). New Jersey Preschool Expansion Assessment Research Study (PEARS). National Institute for Early Education Research. Retrieved from www.ccanj.org.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Olivetti, C., and Petrongolo, B. (2017). The Economic Consequences of Family Policies: Lessons from a Century of Legislation in High Income Countries. Journal of Economic Perspectives. Volume 31, Number 1. Pages 205–230. Retrieved from http://pubs.aeaweb.org.

[6] Krause, E. and Sawhill, I. (2017). What We Know and Don’t Know About the Declining Labor Force Participation Rate. The Brookings Institution.

[7] Steverman, B. (2017). Modern Motherhood Has Economists Worried. Bloomberg. Retrieved from www.bloomberg.com.

[8] Parker, K. and Wang, W. (2013). Modern Parenthood: Roles of Moms and Dads Converge as They Balance Work and Family. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from www.pewsocialtrends.org/.

[9] Brown, B. and Traill, S. (2006). Benefits for All: The Economic Impact of the New Jersey Child Care Industry. The New Jersey Child Care Economic Impact Council. The John S. Watson Institute for Public Policy at Thomas Edison State College.

[10] Detailed data on New Jersey was generated by analyzing the American Community Survey (ACS) Public Use Microdata Sample, also known as PUMS. This allows for a custom analysis of actual responses to the ACS survey. Unless otherwise noted, all findings in Section III were generated from the PUMS analysis.

[11] American Community Survey (ACS), Five-Year Public Use Microdata Sample, 2011-2015.

[12] Advocates for Children of New Jersey (2017). New Jersey Kids Count 2017: A Statewide Profile of Child Well-Being.

[13] National Women’s Law Center (2017). The Wage Gap, State by State. Retrieved from https://nwlc.org/resources.

[14] Vogtman, J. and Schulman, K. (2016). Set Up To Fail: When Low Wage Work Jeopardizes Parents’ and Children’s Success. National Women’s Law Center. Retrieved from https://nwlc.org.

[15] State of New Jersey Department of Human Services (2016). SFY 2016 Income Eligibility Schedules for Publicly Subsidized Child Care Assistance or Services. Retrieved from http://www.state.nj.us/humanservices.

[16] Economic Policy Institute (2015). Family Budget Calculator. Retrieved from www.epi.org/resources/budget/.

[17] Barnett, W.S. and Friedman, A., et al (2017). The State of Preschool 2016: New Jersey Profile. The National Institute for Early Education Research. Retrieved from http://nieer.org.

[18] For background on New Jersey’s Abbott districts, see Education Law Center’s Abbott Overview at http://www.edlawcenter.org/cases/abbott-v-burke/. For more detail on state funded preschool in New Jersey school districts see Education Law Center’s Preschool Data at http://www.edlawcenter.org/research/preschool-data.html.

[19] Barnett, W.S. and Friedman, A., et al (2017). The State of Preschool 2016: New Jersey Profile. The National Institute for Early Education Research. Retrieved from http://nieer.org.

[20] Education Law Center (2017). Preschool Data. Retrieved from www.edlawcenter.org.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Friedman, A., Frede, E., et al (2009). New Jersey Preschool Expansion Assessment Research Study (PEARS). National Institute for Early Education Research. Retrieved from www.ccanj.org.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] State of New Jersey Department of the Treasury (2017). Analysis of Division of Family Development Evaluation Data for Child Care Payments for Eligible Families. Department and Branch Recommendations in New Jersey State Budget Years 2003-2018. Retrieved from www.nj.gov/treasury/omb/publications/archives.shtml.

[26] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2016). “About the Office of Head Start”. Office of Head Start: An Office of the Administration for Children and Families. Retrieved from: https://www.acf.hhs.gov.

[27] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2016). “Head Start Program Facts: Fiscal Year 2016”. Data and Ongoing Monitoring. Retrieved from: https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov.

[28] State of New Jersey Department of Human Services (2016). SFY 2016 Income Eligibility Schedules for Publicly Subsidized Child Care Assistance or Services. Retrieved from http://www.state.nj.us/humanservices.

[29] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Head Start (2016). Program Information Report (PIR) Family Information Report – 2016 – State Level – New Jersey. Retrieved via request from https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov.

[30] Barnett, W.S. and Friedman-Krauss, A. State(s) of Head Start (2016). National Institute of Early Education Research. Retrieved from http://nieer.org/.

[31] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Head Start (2016). Program Information Report (PIR) Family Information Report – 2016 – State Level – New Jersey. Retrieved via request from https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov.

[32] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Head Start (2016). Analysis of Program Information Report (PIR) Family Information Report – 2016 – State Level – New Jersey. Retrieved via request from https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov.

[33] Barnett, W.S. and Friedman-Krauss, A. State(s) of Head Start (2016). National Institute of Early Education Research. Retrieved from http://nieer.org/.

[34] Ibid.

[35] State of New Jersey Department of the Treasury (2017). Division of Family Development Evaluation Data for Child Care Payments for Eligible Families. Department and Branch Recommendations in New Jersey State Budget Years 2003-2018. Retrieved from www.nj.gov/treasury/omb/publications/archives.shtml.

[36] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2016). Office of Child Care. FY 2016 CCDF Allocations. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/occ/resource/fy-2016-ccdf-allocations-including-redistributed-funds#1.

[37] Administration for Children and Families Office of Child Care (2017). State/Territory Profile: New Jersey. State Capacity Building Center. Retrieved from https://childcareta.acf.hhs.gov/state-profiles/profiles/NJ/pdf.

[38] Schulman, K. and Blank, H. (2016). Red Light Green Light: State Child Care Assistance Policies 2016. National Women’s Law Center. Washington, D.C. Retrieved from www.nwlc.org.

[39] Tencza, Jacqueline (2017, June 12). Spokeswoman for New Jersey Division of Family Development. Phone interview.

[40] State of New Jersey Department of the Treasury (2017). Division of Family Development Evaluation Data for Child Care Payments for Eligible Families. Department and Branch Recommendations in New Jersey State Budget Years 2003-2018. Retrieved from www.nj.gov/treasury/omb/publications/archives.shtml.

[41] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2016). Office of Child Care. FY 2015 Preliminary Data Table 9 – Average Monthly Percentages of Children in Care By Age Group (FY 2014). Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/occ.

[42] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2016). Office of Child Care. FY 2015 Preliminary Data Table 7 – Number of Child Care Providers Receiving CCDF Funds. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/occ.

[43] State of New Jersey Department of Human Services (2017). Christie Administration Raises Pay Rates for Certain Child Care Providers [Press release]. Retrieved from http://www.state.nj.us/humanservices.

[44] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2016). Analysis of Office of Child Care. FY 2015 Preliminary Data Table 10 – Reasons for Receiving Care, Average Monthly Percentage of Families. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/occ.

[45] Matthews, Hannah and Walker, Christina (2016). Child Care Assistance Spending and Participation in 2014. Center for Law and Social Policy. Retrieved from http://www.clasp.org.

[46] Schmit, Stephanie and Walker, Christina (2016). Disparate Access: Head Start and CCDBG Data by Race and Ethnicity. Center for Law and Social Policy. Retrieved from www.clasp.org.

[47] Ibid.

[48] New Jersey Association of Child Care Resource and Referral Agencies (2013). The High Price of Child Care 2013: A Study on the Cost of Care in New Jersey. Retrieved from www.childcareconnection-nj.org.

[49] Rutgers Center for Women and Work (2016). New Jersey’s Benefits “Cliff Effect” and Economic Self Sufficiency: Center for Women and Work Fact Sheet. Retrieved from http://smlr.rutgers.edu.

[50] New Jersey Department of Human Services Division of Family Development. Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) Plan for New Jersey FFY 2016-2018. Retrieved from http://www.state.nj.us/humanservices/dfd/programs/child/.

[51] New Jersey Department of Human Services (2008). Child Care and Early Education Service Eligibility Application. Retrieved from www.childcarenj.gov/getattachment/Parents/SubsidyProgram/Subsidy-Application-English.pdf.aspx?lang=en-US.

[52] See Appendix for tables.

[53] See Appendix for calculations.

[54] Barnett, W.S. and Friedman, A., et al (2017). The State of Preschool 2016. The National Institute for Early Education Research. Retrieved from http://nieer.org.

[55] National Women’s Law Center (2017). Workplace Justice: Recently Enacted and Introduced State and Local Fair Scheduling Legislation. Retrieved from: https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Fair-Scheduling-Report-1.30.17-1.pdf.