Every day, hundreds of thousands of New Jersey residents rely on public transit to get around, taking trips to work, school, medical appointments, family visits, and to shop and dine. NJ Transit is at the heart of these daily journeys, helping more than 630,000 people statewide go where they need to be while keeping cars off the road and bringing the state closer to its climate and pollution reduction goals.[i] NJ Transit is an engine of economic opportunity and everyday necessity, particularly for people who do not own or drive a car, as well as low-income, Black, and Hispanic/Latinx residents who are more likely to use mass transit.

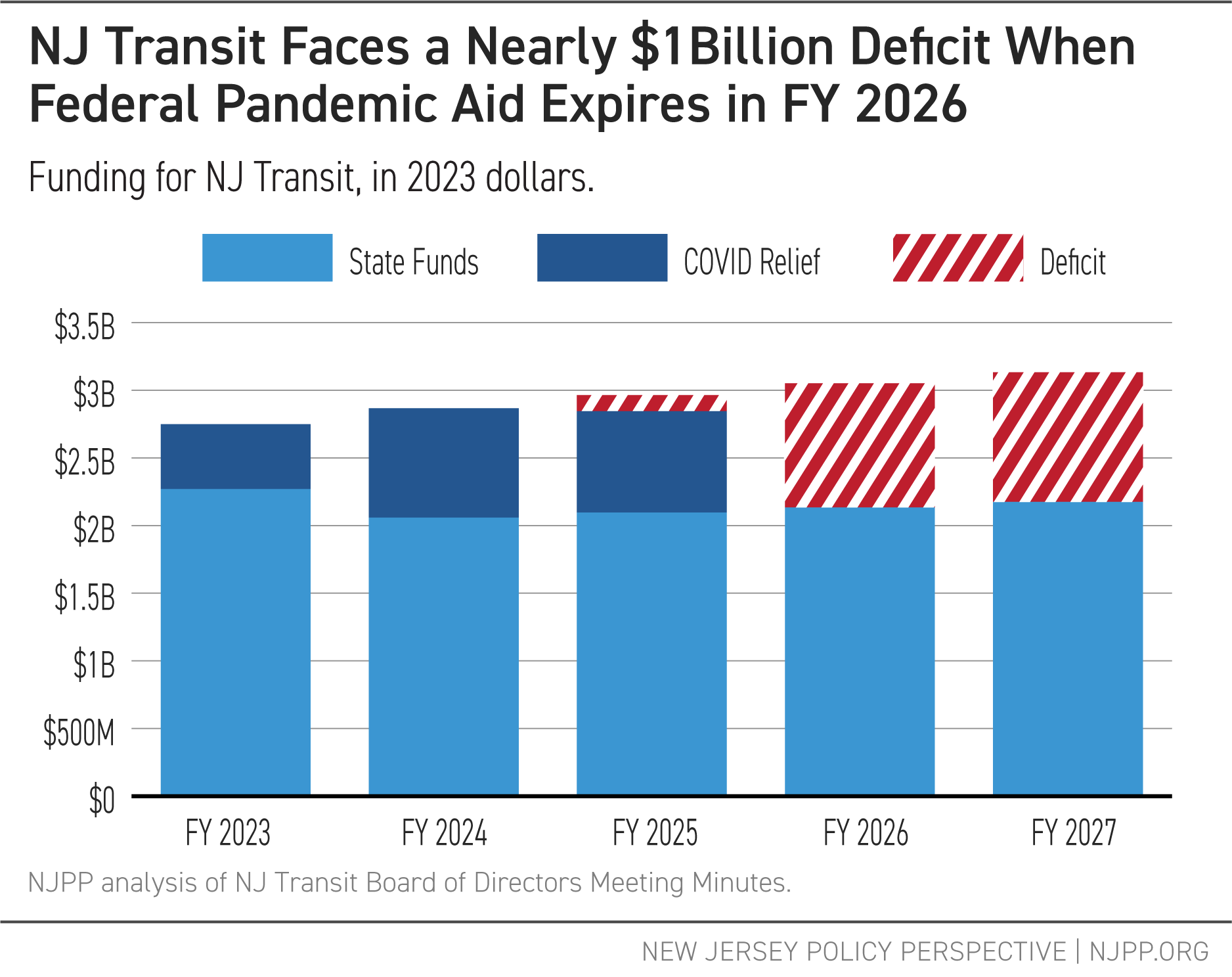

However, the agency’s future is in jeopardy due to years of underfunding, the lack of a stable and dedicated source of revenue, and a looming deficit of nearly $1 billion once federal pandemic assistance expires.[ii] This deficit would constitute nearly one-third of the system’s total budget and, without additional state funding, could lead to dramatic service cuts and fare hikes that would harm everyday commuters and the broader economy.[iii]

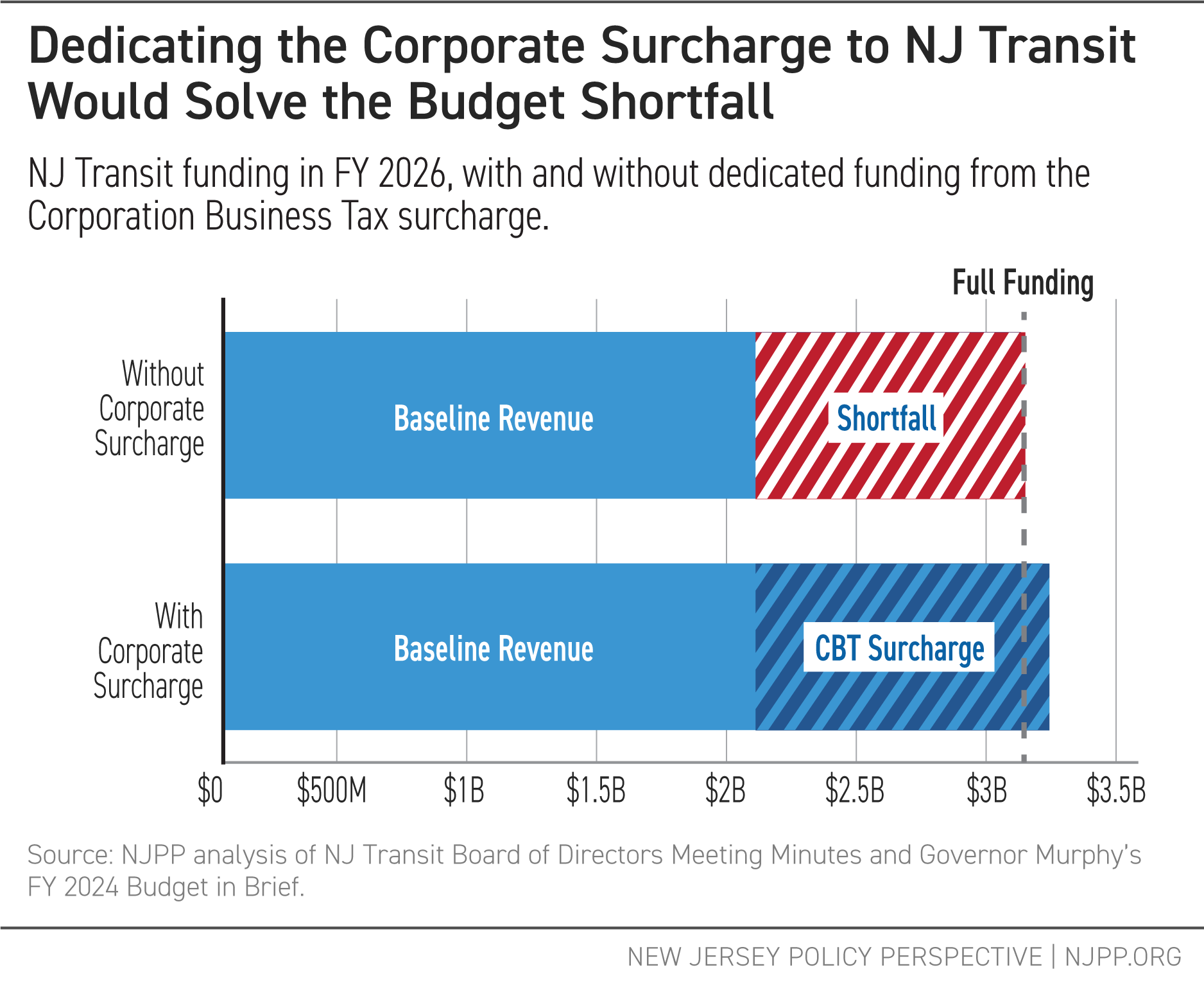

Instead of relying on service cuts and fare hikes, state lawmakers should consider an alternative: have the largest and most profitable corporations help fund NJ Transit, a public service they directly benefit from, by simply extending the Corporation Business Tax surcharge on companies making more than $1 million in profit. The surcharge is only paid by the top 2 percent of corporations earning profits in New Jersey — including many large multinational companies headquartered outside of the state like Amazon and Walmart — providing a fair and stable revenue source that spares small businesses and commuters.[iv] This tax generates $1 billion in revenue annually, filling almost precisely the budget hole left by expiring federal funds and years of state disinvestment.[v]

As corporations earn record-breaking profits and working families struggle with rising prices, taxing multinational corporations to support critical infrastructure that we all benefit from is a fair, responsible, and commonsense solution to fix NJ Transit in the short and long term.[vi]

NJ Transit is Vital to New Jersey’s Economy and Communities

Serving the densest state in the nation and providing direct access to New York City and Philadelphia, NJ Transit connects residents to millions of employment and economic opportunities, essential services, community resources, entertainment, and social activities. Being able to get around safely and reliably, and having transportation options for residents who do not or cannot drive, is vital to the region’s economy and the wellness of communities across New Jersey. A robust mass transit system also supports better health outcomes by significantly reducing trips made by car — an essential service given that transportation is the single largest source of air pollution in the state.

Mobility and Accessibility

Everyone in New Jersey benefits from NJ Transit and the options they provide to get around the state. From the white-collar worker taking the train to their office, to the building maintenance worker taking the bus, to the nurse taking the light rail to get to their shift at the hospital, all types of workers depend on mass transit to provide for their families and keep the state running.

Mass transit is also a critical lifeline for low-income families and those who cannot drive or afford their own car. Nearly half of NJ Transit bus riders do not own a car, more than half have an annual income of less than $35,000, and 80 percent rely on the bus more than five times per week.[vii] The racial divide in commuting is also stark: Black workers are three times as likely as white workers to not have a car at home, while Hispanic/Latinx and Asian-American workers are twice as likely as white workers to not have a car.[viii] Further, households in cities with higher concentrations of people of color, like Jersey City and Newark, are more likely to lack access to a vehicle compared to households statewide.[ix] Mass transit ensures mobility and accessibility not only for these families but also for those who are disabled and cannot drive.

Economic Benefits

NJ Transit’s economic benefits build on the nearly 270 million individual trips made per year, connecting people within the state and beyond.[x] Bus and train rides link people with higher-paid jobs, health care facilities, and higher education opportunities.[xi] In addition to trips within the state, NJ Transit provides residents with direct access to New York City and Philadelphia, as well as connections to job centers across the Northeast Corridor in cities like Boston and Washington, DC. More than 78 million riders use NJ Transit-operated or supported trains and buses to travel into and out of Manhattan, with another 5.2 million riders going into and out of Philadelphia.[xii]

And these trips go beyond everyday commuting for work. A survey of bus riders found that 40 percent of riders use the bus to get to places other than their job, including doctor’s appointments, school, and to shop and dine.[xiii] This means that off-peak service is essential to keep the state’s economy moving. Hundreds of thousands of riders also travel down the shore on the North Jersey Coast Line and to concerts and events at stadiums and performing arts centers in Newark, the Meadowlands, and Atlantic City, attracting people from across the country and generating millions in income annually.[xiv]

Access to these job opportunities not only benefit individual workers and their families, but businesses and the broader economy alike. Businesses benefit from access to a deep and talented pool of workers, and will often move near job centers served by mass transit as a result. This creates a self-reinforcing loop, making states like New Jersey a great place to live and station a business.[xv]

Direct investments in NJ Transit also pay off for the state and the communities it serves. Roughly $5 billion is generated annually through spending on mass transit in the state, creating a return on an investment of two dollars in economic benefits for every dollar spent on NJ Transit.[xvi]

Health and Environment

Robust public transit also benefits the state by reducing air pollution and improving the health of New Jersey families and the environment. With New Jersey’s expansive highway and road networks, the transportation sector is the state’s biggest source of air pollution.[xvii] Replacing car trips with a bus or train helps reduce air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions everywhere, particularly in communities overburdened by pollution. In 2019, NJ Transit displaced enough carbon dioxide to replace more than 800,000 passenger cars.[xviii] Increasing the use of public transportation will help New Jersey meet its goal of achieving an 80 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.[xix]

More access to mass transit can also improve public health by reducing traffic congestion and injuries from car crashes. With fatal crashes and pedestrian fatalities on the rise, traffic safety should be viewed as a matter of public health. New Jersey has seen an increase in fatal crashes over the past two years, and road traffic crashes remain the leading cause of death for people under the age of 54 in the United States.[xx]

NJ Transit is Underfunded and Faces a Catastrophic Fiscal Cliff

Despite the crucial role of NJ Transit in morning commutes and the state’s economy, state lawmakers have routinely underfunded the agency over the last three decades. NJ Transit also lacks a dedicated and stable source of state funding, unlike comparable transit agencies across the country, making it near-impossible to balance annual budgets without forgoing capital improvements or raiding funds from other state programs. Now, with a one-time infusion of federal pandemic aid about to expire, NJ Transit faces a looming $1 billion budget shortfall that could lead to catastrophic service cuts and fare hikes.

Decades of Disinvestment

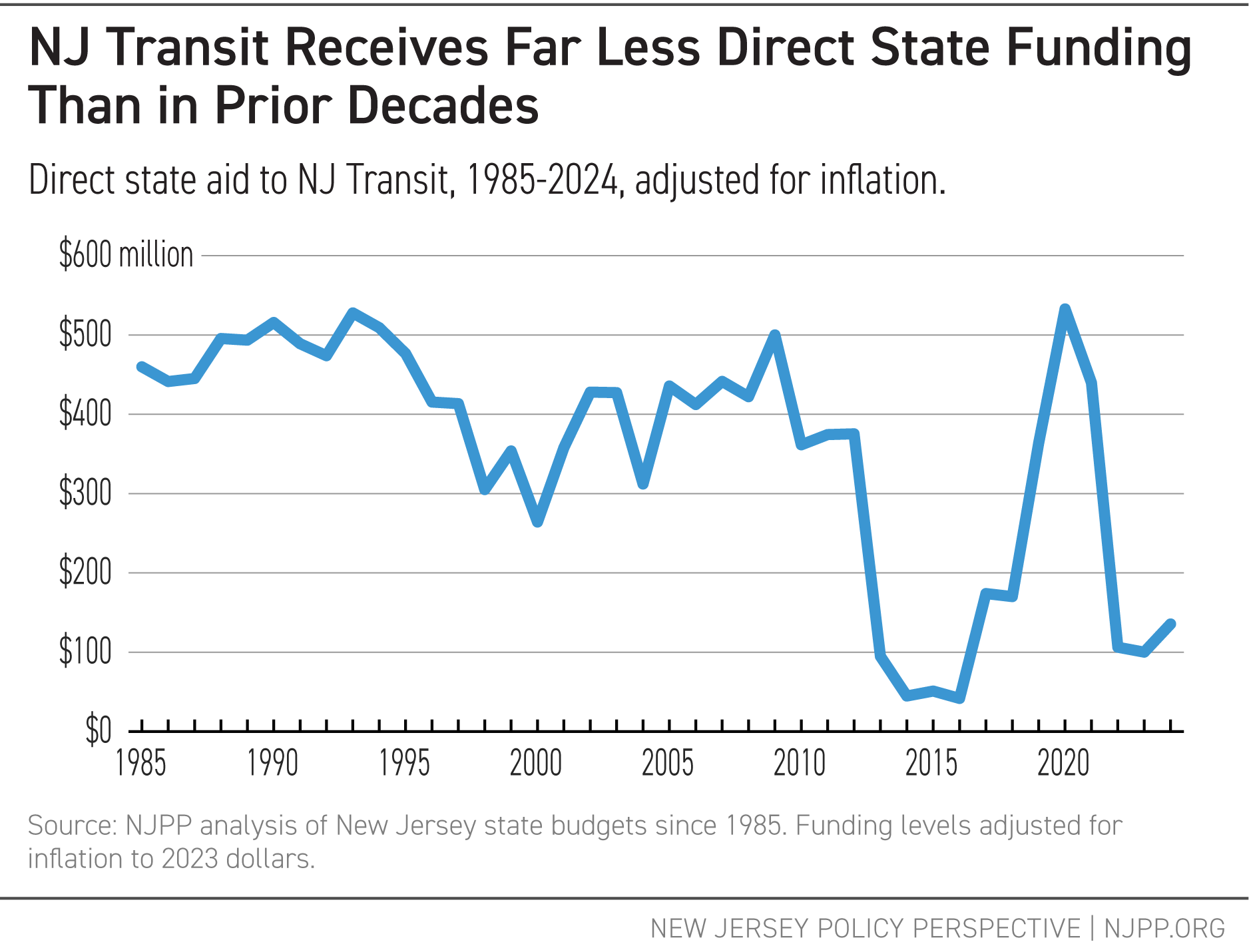

For decades, NJ Transit has not received enough state funding to cover its expenses, resulting in overcrowded buses, frequent train cancellations, and delays to much-needed service expansions like the Hudson-Bergen Light Rail. This underfunding is exemplified by the annual transfer of funding from NJ Transit’s capital budget — meant for updating and building new physical infrastructure — to cover annual operating costs, a practice that state lawmakers have allowed since 1990. Even so, lawmakers have historically provided NJ Transit with robust state funding until direct state aid was cut by 90 percent during the Christie administration.[xxi] As recently as 2009, the state invested $500 million annually in NJ Transit — far more than the $140 million direct state aid in the Fiscal Year (FY) 2024 budget.[xxii]

To cover its operating expenses, NJ Transit’s budget routinely raids hundreds of millions of dollars from other dedicated funds, most notably the Clean Energy Fund and NJ Transit’s own capital investment fund. Both raids are counterproductive: money from the Clean Energy Fund should support investments in new, green energy sources and technology, and raiding capital investments has left NJ Transit with more train breakdowns than its peer agencies.[xxiii]

Lack of state funding has also resulted in an overreliance on farebox revenue, i.e., commuter tickets and fares, a revenue source that is volatile year over year.[xxiv] Public transportation is a public service that benefits the state as a whole, not a “business” that should be expected to make a profit. Relying disproportionately on riders to balance NJ Transit’s budget functions as a regressive tax — shifting the financial burden on residents least able to afford it — and will never lead to a fully-funded, balanced budget.[xxv] Across the country, transit agencies more reliant on farebox revenue, including NJ Transit, are facing steeper budget shortfalls than agencies with stronger public investment.[xxvi]

Reliance on Pandemic Aid

Already operating on a shaky foundation, NJ Transit and its finances were especially vulnerable to the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent dip in ridership. In the years since, lawmakers have balanced the agency’s budget with an infusion of federal pandemic assistance from the CARES Act and American Rescue Plan. In total, NJ Transit will have received approximately $4.5 billion in federal pandemic aid, including roughly $800 million for the current fiscal year and $750 million next year in FY 2025, after which the aid expires.[xxvii]

A look at NJ Transit’s current budget shows that the agency faces deficits of approximately $1 billion — nearly 30 percent of its budget — once the pandemic aid runs out.

As pandemic-related federal relief ends with no congressional action on the horizon, state lawmakers will have to grapple with a severely underfunded and overstretched agency that service cuts and fare hikes alone will not be able to solve.[xxviii]

Lack of Dedicated Funding

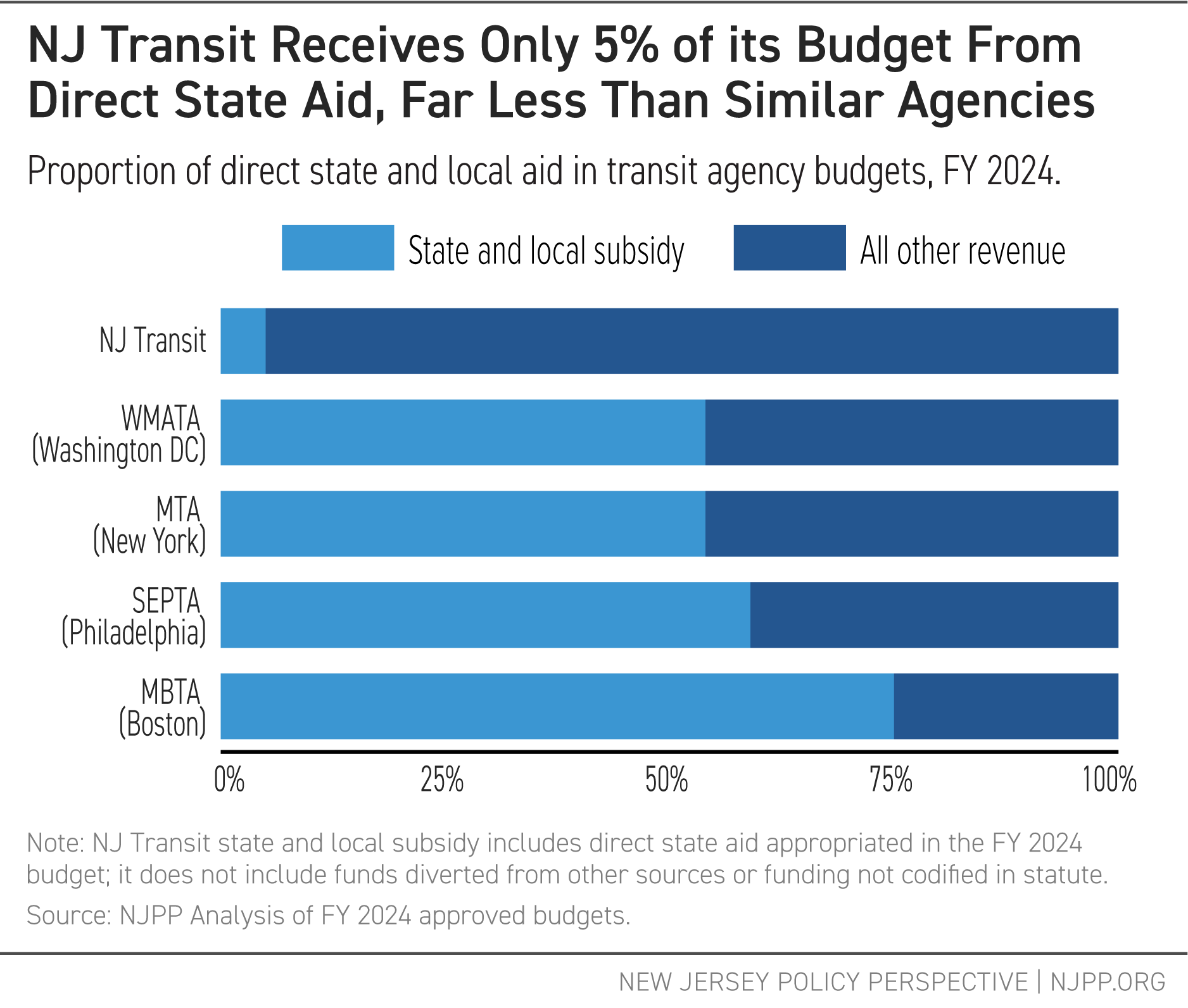

NJ Transit is not alone in experiencing a drop in ridership after the pandemic; however, it remains the only statewide transportation agency of its kind without dedicated state funding.[xxix]

While comparable transit agencies receive more than half of their funding from dedicated state and local revenue sources, a mere 5 percent of NJ Transit’s budget comes from direct state aid. Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, California, and Illinois fund their mass transit systems through a statutorily dedicated portion of the sales tax.[xxx] New York and Oregon fund their transit systems with corporate and payroll taxes on businesses within their service areas.[xxxi]

Recently, New York resolved a $600 million deficit without drastic fare hikes or service cuts by raising taxes on corporations, many of which benefit from public transit.[xxxii] Not only is the agency fully funded and with a balanced budget for the first time in 20 years, but projections show that this new revenue stream will help balance MTA’s budget through 2027. Dedicated revenue allows agencies to sustain operations in the short term as well as engage in long-term planning to ensure continued high-quality service for riders everywhere.

Recommendation: Dedicate the Corporate Surcharge to Fund NJ Transit

To balance NJ Transit’s budget and put the agency on a path of long-term stability, any dedicated revenue must be substantial enough to cover the nearly $1 billion deficit and protect against future crises and shocks. New funding should also come from those with the highest incomes and wealth rather than the low-income residents for whom fares already serve as a de facto tax.[xxxiii] By simply extending the Corporation Business Tax surcharge, New Jersey can save NJ Transit with revenue generated by the world’s biggest and wealthiest corporations that have long benefited from the state’s infrastructure and workforce.

A Fair Source of Revenue

With many families struggling to keep up with rising costs, corporate profits have soared to record levels.[xxxiv] This concentration of wealth and resources has not only failed to trickle down to workers and their families, but has also coincided with significant corporate tax cuts at the state and federal levels. Most notably, the Trump-era tax cuts lowered the federal corporate tax rate to its lowest level since 1946.[xxxv] Tax avoidance is also on the rise, even with these lower tax rates, with more than one-third of large corporations paying nothing in taxes.[xxxvi] Having profitable corporations that directly benefit from public transit help pay for those investments would promote fairness, spare low- and middle-income riders from drastic fare increases, and provide NJ Transit with a stable source of revenue now and into the future.

And when states have cut corporate tax rates, the promised economic boom times rarely reach workers, with corporate tax rates having little correlation with income growth.[xxxvii] What corporate tax cuts do correlate with is rising inequality, with lower corporate taxes leading to more concentration of wealth in the top 1 percent of households.

When corporations pay a state tax, the dollars come from shareholders and highly paid executives, not average workers or consumers.[xxxviii]

Dedicating the CBT Surcharge

New Jersey has already recognized how taxing highly profitable corporations can advance equity, fiscal responsibility, and smart economic investments. Enacted in 2018, the Corporation Business Tax (CBT) surcharge is a 2.5 percent tax on corporations with over $1 million in annual profits. This $1 billion revenue source targets the most profitable corporations in the world, but it is set to expire at the end of 2023 unless lawmakers extend it.

Because this tax is applied to profits, not revenue, the few affected corporations would remain incredibly profitable. And because the tax is applied to profits earned in New Jersey, not solely on companies headquartered in the state, it is primarily paid by large multinational corporations — like Amazon, Walmart, and Bank of America — that have no incentive to stop doing business in New Jersey. The $1 million profit threshold ensures that only the most profitable 2 percent of corporations operating in the state will pay it, meaning that 98 percent of New Jersey businesses will not pay the surcharge at all.[xxxix] And since the surcharge has been a part of New Jersey’s tax code since 2018, extending it would not create a new tax or expense for the roughly 2,500 corporations that currently pay it.

To fix NJ Transit and give it the financial resources it needs to thrive in the coming decades, lawmakers should dedicate revenue from the CBT surcharge to pay for NJ Transit operations. The surcharge is estimated to bring in $1 billion in annual revenue, according to budget documents released by the Murphy administration, just as NJ Transit faces a nearly $1 billion budget deficit.[xl] A dedication of corporate surcharge funds will allow the agency to reduce its reliance on money from its capital fund and the Clean Energy Fund, allowing those dollars to go to their intended uses rather than patching over the system’s operations.[xli]

It is worth noting that NJ Transit is not the only agency or piece of state infrastructure that will require additional funding once federal pandemic assistance expires. Local school districts and child care providers, for example, are just two critical sectors that will need state investment to replace expiring federal aid.[xlii]

If state lawmakers do not want to use the entire CBT surcharge on transit so they have additional funding for other programs, they should dedicate at least $500 million to NJ Transit to bring state aid back to historical levels prior to the Christie administration. When adjusted for inflation, state investment in NJ Transit averaged over $400 million in annual spending during the 1980s, early 1990s, and during the pre-recession 2000s.[xliii] To be clear, this would not fully resolve NJ Transit’s budget deficit, but it would likely stave off the most disastrous cuts and fare hikes — if combined with other funding measures — while providing lawmakers time to find alternative funding sources.

Whichever path lawmakers choose, extending a tax on wealthy corporations to stabilize and fund NJ Transit can alleviate its fiscal woes and advance New Jersey’s economic and environmental goals, without pushing those costs onto low-income residents.

The Alternative is a Disaster

If lawmakers do not find a new, dedicated source of revenue for NJ Transit, the alternative is nothing short of a disaster. Given the scale of NJ Transit’s budget deficit, balancing the agency’s budget primarily through fare hikes and service cuts could lead to a transit “death spiral,” a vicious cycle in which higher fares and reduced service lead to fewer riders, less revenue, and further cuts.[xliv] This would gut what remains of NJ Transit’s ridership base, jeopardizing the state’s economic growth, cutting off access to jobs from hundreds of thousands of residents, and dooming any progress towards the state’s climate and emission reduction goals. It shouldn’t have taken a crisis for lawmakers to finally dedicate funding to NJ Transit, but with a nearly $1 billion shortfall and no good alternative, they have no choice but to act.

End Notes

[i] NJ Transit averaged 637,100 rides on weekdays in the 2nd quarter of fiscal year 2023. See Appendix A, NJ Transit Minutes for April 19, 2023, https://content.njtransit.com/sites/default/files/board/meeting_minutes/2023_04_19_OpenSessEXP.pdf.

[ii] The nearly $1 billion in NJ Transit deficits can be seen in Appendix D of the NJ Transit Minutes for April 19, 2023, https://content.njtransit.com/sites/default/files/board/meeting_minutes/2023_04_19_OpenSessEXP.pdf at exh. B, app’x D, p. 64876.

[iii] John Reitmeyer, NJ Transit Fare Hikes: Only a matter of time? NJ Spotlight News, Aug. 21, 2023, https://www.njspotlightnews.org/2023/08/nj-transit-money-woes-make-fare-hikes-service-cuts-possible/. The overall budget of NJ Transit for FY 2026 is approximately $3 billion. See Appendix D of the NJ Transit Minutes for April 19, 2023, https://content.njtransit.com/sites/default/files/board/meeting_minutes/2023_04_19_OpenSessEXP.pdf at exh. B, app’x D, p. 64876.

[iv] N.J. Stat. 54:10A-5.41 (2023).

[v] The nearly $1 billion in NJ Transit deficits can be seen in Appendix D of the NJ Transit Minutes for April 19, 2023, https://content.njtransit.com/sites/default/files/board/meeting_minutes/2023_04_19_OpenSessEXP.pdf at exh. B, app’x D, p. 64876.

[vi] Governor’s FY 2024 Budget in Brief, https://www.state.nj.us/treasury/omb/publications/24bib/BIB.pdf at p. 65.

[vii] New Jersey Transit, NJ Transit Sustainability Plan 2023: Draft (2023) at p. 19 https://content.njtransit.com/sites/default/files/sustainability/NJ%20TRANSIT%20Sustainability%20Plan_DRAFT_05312023.pdf

[viii] National Equity Atlas, Car Access: New Jersey 2020, Percent of households without a vehicle by race/ethnicity, https://nationalequityatlas.org/indicators/Car_access?geo=02000000000034000 (last accessed Sept. 21, 2023). See generally Demos, To Move Is To Thrive: Public Transit and Economic Opportunity for People of Color, Algernon Austin, November 15, 2017. https://www.demos.org/research/move-thrive-public-transit-and-economic-opportunity-people-color

[ix] See National Equity Atlas, Car Access: New Jersey vs. Newark, NJ, 2020, Percent of households without a vehicle by race/ethnicity, https://nationalequityatlas.org/indicators/Car_access?geo_compare=07000000003451000&geo=02000000000034000 (last accessed Sept. 21, 2023); National Equity Atlas, Car Access: New Jersey vs. Jersey City, NJ, 2020, Percent of households without a vehicle by race/ethnicity, https://nationalequityatlas.org/indicators/Car_access?geo_compare=07000000003436000&geo=02000000000034000 (last accessed Sept. 21, 2023).

[x] New Jersey Transit, About Us, last accessed Sept. 17, 2023, https://www.njtransit.com/about/about-us.

[xi] See Jon Carnegie, Deva Deka & Andrea Lubin, Marketing Research for the Quantifiable Benefits of Transit in New Jersey, New Jersey Dep’t of Transportation Bureau of Research Paper No. FHWA-NJ-2021-006, https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/61821 at 35.

[xii] Jon Carnegie, Deva Deka & Andrea Lubin, Marketing Research for the Quantifiable Benefits of Transit in New Jersey, New Jersey Dep’t of Transportation Bureau of Research Paper No. FHWA-NJ-2021-006, https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/61821 at 3.

[xiii] https://tstc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Bus-Survey-Results-Report.pdf

[xiv] Jon Carnegie, Deva Deka & Andrea Lubin, Marketing Research for the Quantifiable Benefits of Transit in New Jersey, New Jersey Dep’t of Transportation Bureau of Research Paper No. FHWA-NJ-2021-006, https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/61821 at 36.

[xv] Siqi Zheng, MIT Climate Portal, Explainer: Public Transportation, Feb. 21, 2023, https://climate.mit.edu/explainers/public-transportation.

[xvi] See Jon Carnegie, Deva Deka & Andrea Lubin, Marketing Research for the Quantifiable Benefits of Transit in New Jersey, New Jersey Dep’t of Transportation Bureau of Research Paper No. FHWA-NJ-2021-006, https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/61821 at 2.

[xvii] A recent federal estimate puts the transportation sector at 47.9% of New Jersey’s carbon emissions. U.S. Energy Information Administration, Table 3: State Energy-Related Carbon Dioxide Emissions by Sector, 2021, July 12, 2023, https://www.eia.gov/environment/emissions/state/excel/table3.xlsx.

[xviii] Analysis of NJ Transit Draft Sustainability Plan, p. 6. https://content.njtransit.com/sites/default/files/sustainability/NJ%20TRANSIT%20Sustainability%20Plan_DRAFT_05312023.pdf. Analysis done using NJ Transit carbon impact and US EPA greenhouse gas equivalencies calculator. Environmental Protection Agency, Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator (July 2023), https://www.epa.gov/energy/greenhouse-gas-equivalencies-calculator

[xix] New Jersey Dep’t of Environmental Protection, New Jersey’s Global Warming Response Act 80×50 report, p. v, https://dep.nj.gov/wp-content/uploads/climatechange/nj-gwra-80×50-report-2020.pdf.

[xx]New Jersey State Police Fatal Accident Investigation Unit, Fatal Motor Vehicle Crash Comparative Data Report for the State of New Jersey, p. 2 (2022) https://nj.gov/njsp/information/pdf/fcr/2021_fatal_crash_report.pdf; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Road Traffic Injuries and Deaths – A Global Problem, Jan. 10, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/injury/features/global-road-safety/index.html.

[xxi] Emma G. Fitzimmons & Patrick McGeehan, New Jersey Transit, a Cautionary Tale of Neglect, N.Y. Times, Oct. 13, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/14/nyregion/new-jersey-transit-crisis.html

[xxii] NJPP analysis of NJ budget documents from FY 1985 to present.

[xxiii] See Alex Ambrose, New Jersey Policy Perspective, Stop the Raids: The Clean Energy Fund Should Fund Clean Energy, Jan. 12, 2023, https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/stop-the-raids-the-clean-energy-fund-should-fund-clean-energy/. Elise Young, NJ Transit’s Creaky, Empty Trains Stir Worry of Fare Increases, Bloomberg, Feb. 24, 2023, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-02-24/nj-transit-delays-hit-record-high-despite-gov-murphy-pledge-to-fix-trains

On the capital-to-operating raid, the New Jersey Department of Transportation notes that because of underfunding, NJ Transit has to use capital funding for basic maintenance and operations, rather than on long-term purchasing of new trains, buses, and equipment. See Nikita Biryukov, No dedicated funding source for NJ Transit this year, budget chair says, New Jersey Monitor, May 4, 2023, https://newjerseymonitor.com/2023/05/04/no-dedicated-funding-source-for-nj-transit-this-year-budget-chair-says/.

[xxiv] Over the past two decades, farebox revenue has fluctuated from highs of over $1 billion to lows of $375 million during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

[xxv] Based on 2021 consumer expenditure data, the average household in the bottom 10 percent in income spent roughly 2.3% of income on public and other transportation, compared with a mere 0.5% in the top 10 percent. See Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Expenditure Surveys, Table 1110, Deciles of income before taxes: Annual expenditure means, shares, standard errors, and coefficients of variation (2022). https://www.bls.gov/cex/tables/calendar-year/mean-item-share-average-standard-error/cu-income-deciles-before-taxes-2021.pdf

[xxvi] The Metropolitan Transportation Authority has analyzed its finances and identified volatile farebox revenue as a prime driver of its fiscal risks. See Office of the State Deputy Comptroller for the City of New York, Fare Revenue Considerations for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (November 2022), https://www.osc.state.ny.us/reports/osdc/fare-revenue-considerations-metropolitan-transportation-authority.

[xxvii] Governor’s Disaster Recovery Office, COVID-19 State Funding Financial Table, Responsible Agency: NJ Transit, last updated June 30, 2023, https://gdro.nj.gov/tp/en/financial-analysis/table-view/state?bureau=376369859&sortColumn=agency&sortValue=asc&pageSize=15&pageOffset=0&lang=en.

[xxviii] Transit agencies were fortunate that unexpended pandemic aid avoided the chopping block, as a target of House Republican cuts to federal aid nationally. See Ian Duncan & Justin George, Ailing Transit Agencies to Keep Pandemic Funding in Debt Ceiling Deal, Washington Post, June 2, 2023 https://www.washingtonpost.com/transportation/2023/06/02/covid-aid-transit-debt-ceiling/.

[xxix] American Public Transportation Association, Policy Brief: Public Transit Agencies Face Severe Fiscal Cliff, June 2023, p. 2 https://www.apta.com/wp-content/uploads/APTA-Survey-Brief-Fiscal-Cliff-June-2023.pdf

[xxx] Pennsylvania deposits 4.4% of sales tax into its Public Transportation Trust Fund. See Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority, Fiscal Year 2024 Operating Budget, Fiscal 2025-2029, Financial Projections (2023), https://planning.septa.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/FY2024-Operating-Budget-Proposal-4.pdf, p. 80; Phineas Baxandall, Massachusetts Budget and Policy Center, How Slow Sales Tax Growth Causes Funding Problems for the MBTA, Jan. 10, 2018, https://www.massbudget.org/reports/pdf/MBTA%20Sales%20Tax%20Explainer%20FINAL%201-8-2018.pdf p. 1; California has two separate dedicated funds for transit, one based on a quarter-cent of the general sales tax and a separate formula for state transit assistance, see Caltrans, Transportation Development Act, accessed Sept. 21, 2023, https://dot.ca.gov/programs/rail-and-mass-transportation/transportation-development-act; Illinois Dep’t of Revenue, Mass Transit District Sales Tax, accessed Sept. 21, 2023, https://tax.illinois.gov/localgovernments/masstransit.html.

[xxxi] Trimet, Payroll and Self-Employment Tax Information, Employer Payroll Tax, accessed Sept. 21, 2023, https://trimet.org/taxinfo/#employer

[xxxii] Metropolitan Transit Authority, MTA Announces Balanced Budget Through 2027 in July Financial Plan, July 17, 2023, https://new.mta.info/press-release/mta-announces-balanced-budget-through-2027-july-financial-plan.

[xxxiii] For an overview on how progressive taxes in which higher-income and higher-wealth residents pay a higher effective tax rate than their lower-income neighbors, see Carl Davis & Meg Wiehe, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Taxes and Racial Equity, Mar. 31, 2023, https://itep.org/taxes-and-racial-equity/. For the de facto tax imposed on low-income residents, see endnote 25 above.

[xxxiv] Corporate profits in Q2 2023 were 38 percent higher than they were in Q2 2019, at nearly $3.2 trillion. U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, National income: Corporate profits before tax (without IVA and CCAdj) [A053RC1Q027SBEA], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/A053RC1Q027SBEA, September 6, 2023.

[xxxv] Tax Policy Center, Historical Corporate Income Marginal Tax Rates, Tax Years 1942-2022, February 2022. https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/statistics/marginal-corporate-tax-rates

[xxxvi] Steve Wamhoff, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, GAO Report Confirms: Trump Tax Law Cut Corporate Taxes to Rock Bottom, Jan. 13, 2023, https://itep.org/government-accountability-office-report-confirms-trump-tax-law-cut-corporate-taxes-increased-corporations-paying-zero-taxes/

[xxxvii] Josh Bivens, Economic Policy Institute, Reclaiming Corporate Tax Revenues, April 14, 2022, https://www.epi.org/publication/reclaiming-corporate-tax-revenues/.

[xxxviii] William G. Gale & Samuel I. Thorpe, Brookings Institution, Rethinking the incidence of the corporate income tax, May 10, 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/rethinking-the-incidence-of-the-corporate-income-tax/.

[xxxix] Sheila Reynertson, New Jersey Policy Perspective, Stop the Sunset: Corporate Tax Cut Would Benefit the Biggest and Most Profitable Businesses (Feb. 22, 2023), https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/stop-the-sunset-corporate-tax-cut-would-benefit-the-biggest-and-most-profitable-businesses/

[xl] See Governor’s FY 2024 Budget in Brief (2023) https://www.state.nj.us/treasury/omb/publications/24bib/BIB.pdf at p. 65.

[xli] See Alex Ambrose, New Jersey Policy Perspective, Stop the Raids: The Clean Energy Fund Should Fund Clean Energy, Jan. 12, 2023, https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/stop-the-raids-the-clean-energy-fund-should-fund-clean-energy/. On the capital-to-operating raid, Transportation Commissioner Diane Gutierrez-Scaccetti notes that because of underfunding, NJ Transit has to use capital funding for basic maintenance and operations, rather than on long-term purchasing of new trains, buses, and equipment. See Nikita Biryukov, No dedicated funding source for NJ Transit this year, budget chair says, New Jersey Monitor, May 4, 2023, https://newjerseymonitor.com/2023/05/04/no-dedicated-funding-source-for-nj-transit-this-year-budget-chair-says/.

[xlii] See Peter Chen et al., New Jersey Policy Perspective, Red Flags Amid a Sea of Green: Breaking Down New Jersey’s FY 2024 Budget, Aug. 8, 2023, https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/red-flags-amid-a-sea-of-green-breaking-down-new-jerseys-fy-2024-budget/.

[xliii] See Chart 1 above.

[xliv] Colleen Wilson, NJ Transit has had many fiscal crises. Here’s why the one that’s looming will be worse, NorthJersey.com, Jul. 17, 2023, https://www.northjersey.com/story/news/transportation/2023/07/17/nj-transit-fare-increases-service-cuts-new-fiscal-crisis/70407492007/