Every year, New Jersey legislators make choices that shape our communities through the state budget. The budget reveals short-term and long-term priorities of the state and is, at its very core, a moral document. It is how we pool all of our resources together, mainly through taxes, to fund vital programs and essential services that benefit all of us, including public schools and colleges, highways, mass transit, public-health infrastructure, and the social safety net. Communities, programs, services, and lives depend on the state budget.

Yet, despite the importance of the budget, many New Jersey residents do not understand the budget document or process, as they are complicated and rarely transparent. There is also a significant lack of information about how changes in the budget help or harm specific programs and services that are important to the overall economic and social health of the state, or how those programs and services are funded ー or, in many cases, underfunded. This explainer demystifies the state budget, including where the money comes from and goes, how the budget is created, and how residents can be a part of the process.

The Budget: What is it?

The state budget is a formal declaration of where public funds will be allocated. It is also a piece of legislation known as the Appropriations Act, which is passed by the Legislature and signed into law by the Governor every year. As such, it determines whether taxes increase or decrease, which residents and businesses will shoulder those changes, and how the state will gain and distribute additional revenue. This is important because policies that govern our shared investments should ensure that all people, regardless of their race, gender, income, or address, get a fair shot at economic opportunity and financial stability.

The budget is drafted with input from the Governor, state departments and agencies, the Legislature, residents, and after reading this explainer, you!

Where Does the Money Go?

The New Jersey budget funds programs and services that directly benefit the lives of all 8.9 million residents across the state. Through the budget, the state provides aid to 1.37 million students in 584 operating school districts[i] and supports over 300,000 college students attending New Jersey’s 30 public universities and colleges.[ii] It funds salaries and pensions for almost 70,000 state employees[iii] who keep the state government running and provides aid to local municipalities (read: cities, boroughs, townships) so they can meet the unique needs of their communities. The budget also funds critical safety net programs for when families fall on tough times, and many other things we tend to take for granted, such as clean air and water, reliable transit infrastructure, enforcement of labor laws, and much more. It is difficult to find anything that is not touched by the state government.

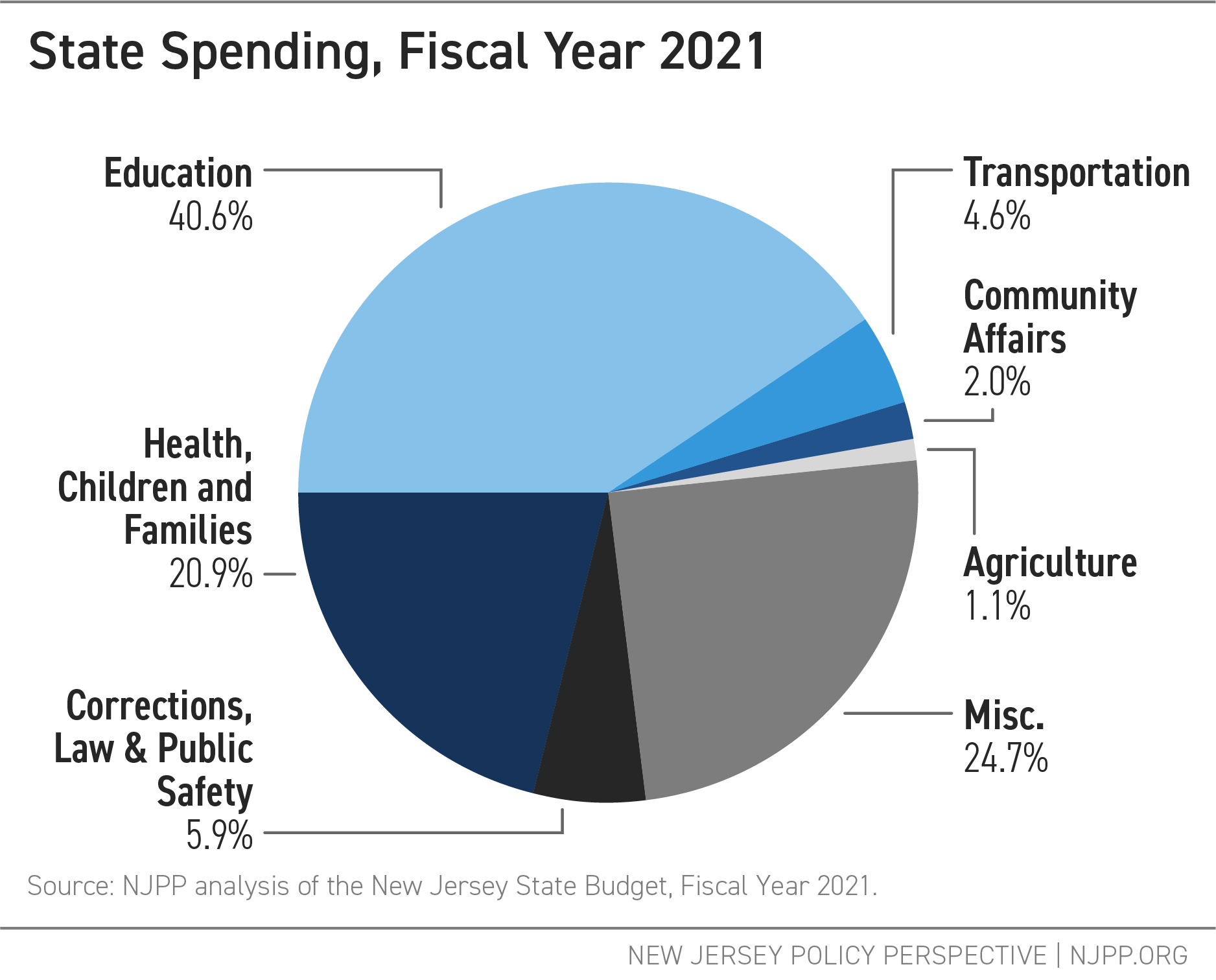

The largest areas of the budget are education and health and human services, which includes needs-based programs for families with limited income like Social Security Insurance (SSI) and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF).[iv] The chart below outlines some of the major expenditures in the budget for Fiscal Year 2021.[v]

Given that Education and Health and Human Services have long been the state’s largest investments, it’s worth exploring some key program areas and how they are impacted by the budget.

Education

Education accounts for the largest percentage of state appropriations, or money dedicated for a certain purpose ー and for good reason. High-quality public schools are a building block of New Jersey communities, as education spending is fundamental to advancing equity, building a strong workforce, and promoting social mobility. There are almost 1.4 million children enrolled in New Jersey public schools, and the quality of their education determines the future prosperity of the state.[vi] State spending on education goes toward funding things like textbooks and other supplies for students, fee waivers for activities and testing for low-income students, special education accommodations, and salaries and pensions for teachers, counselors, nurses, and other staff. It also includes costs associated with keeping public schools safe places to learn that are free of asbestos, lead, and other contaminants.

While New Jersey is known for having some of the best schools in the country, the state has routinely underfunded its school aid formula — sometimes by as much as $1 billion each year.[vii] There have been some attempts to close this funding gap, but they have fallen short and the state is backsliding.[viii] Further, salaries for many teachers and support staff are still alarmingly low,[ix] many schools still do not have what they need to be safe and effective institutions of learning, and guidance counselors and social workers are either overworked or have been let go to cut costs.[x] Until the state fully funds public education, some school districts will remain under-resourced and ill-equipped to provide students with a quality education. This inequality often falls along lines of race and class, underscoring the need for continued investment in public schools so all our children receive the education they deserve.

Health and Human Services

The Department of Human Services (DHS) is home to several critical safety net programs that help to keep New Jersey residents healthy. They include NJ FamilyCare, the state’s public health insurance program, which provides coverage for children, low-income adults, and the elderly; WorkFirst NJ, the state’s welfare program, which provides cash assistance to families having trouble affording basic needs; and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), the state’s food assistance program, which helps low-income people put food on the table. DHS also provides support for residents with substance abuse issues, families in need of affordable child care, and housing assistance for people with developmental disabilities. Moreover, DHS provides critical support for the elderly with subsidized drugs for seniors, funds for long-term care facilities, and on-site investigations in cases of abuse or neglect.

The Department of Health makes up the state’s public health infrastructure and is the first line of defense in responding to public health crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic. They respond directly by disseminating information and helping connect individuals with critical resources, and they respond indirectly by funding local health initiatives in communities. The Department of Health also keeps some of the most vulnerable people in our state healthy through prevention education and the establishment of Harm Reduction Centers.

With nearly four in ten New Jersey residents struggling to make ends meet,[xi] a growing number of people experiencing substance use and mental health disorders, and an aging population that requires care and support, continued investments in a health infrastructure and robust social safety net are needed to maintain a strong quality of life for millions of New Jersey residents.

Where Does the Money Come From?

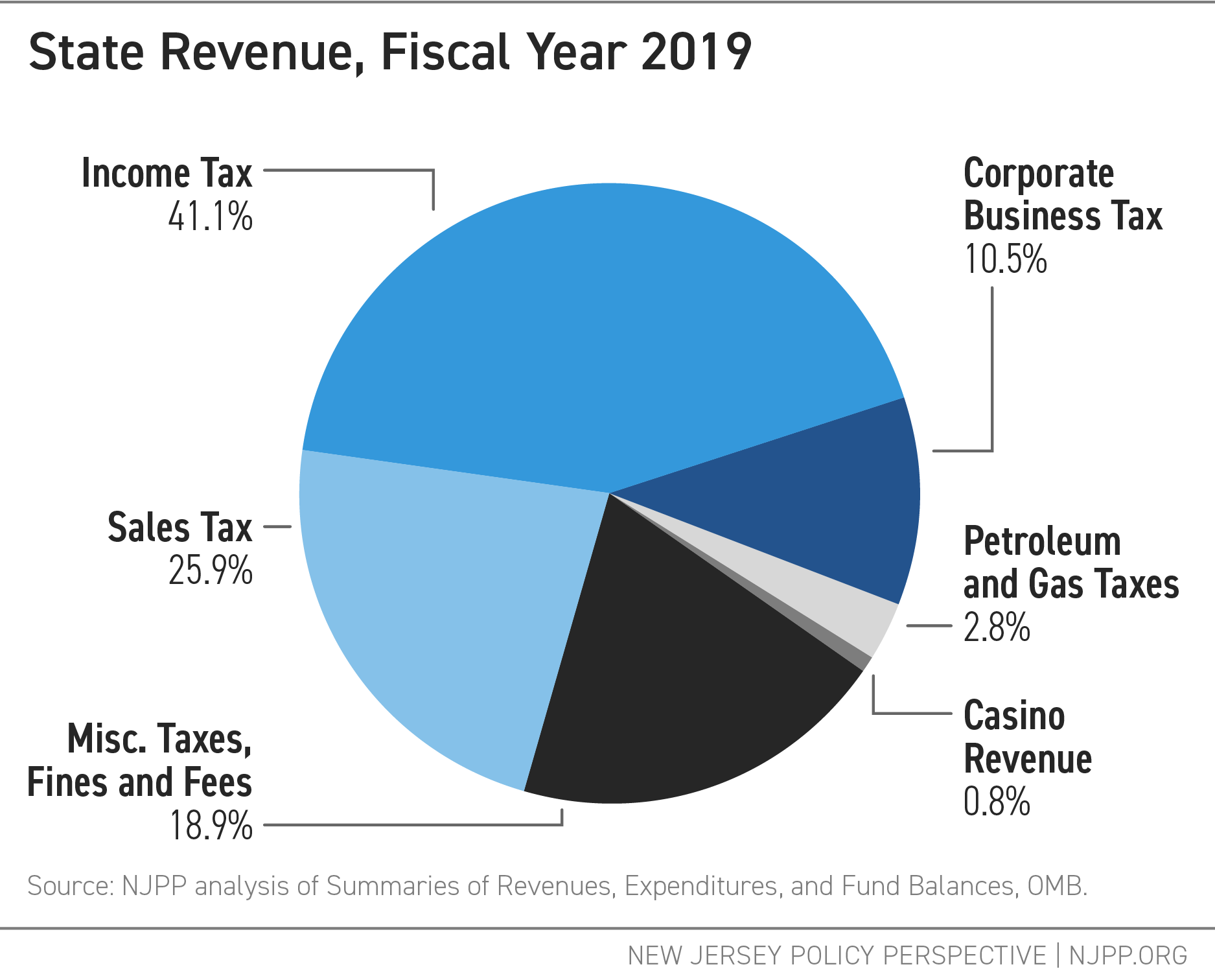

New Jersey, like all states, funds the state government with revenue from taxes, fines and fees, and transfers from the federal government.

A majority of the state’s revenue comes from the income tax, sales tax, and the corporate business tax (CBT), which account for approximately 75 percent of the state budget. Other major taxes include cigarette, alcohol, and motor fuel taxes. The state also generates revenue through various departmental fees, including marriage licenses, hunting and fishing licenses, and parking tickets.

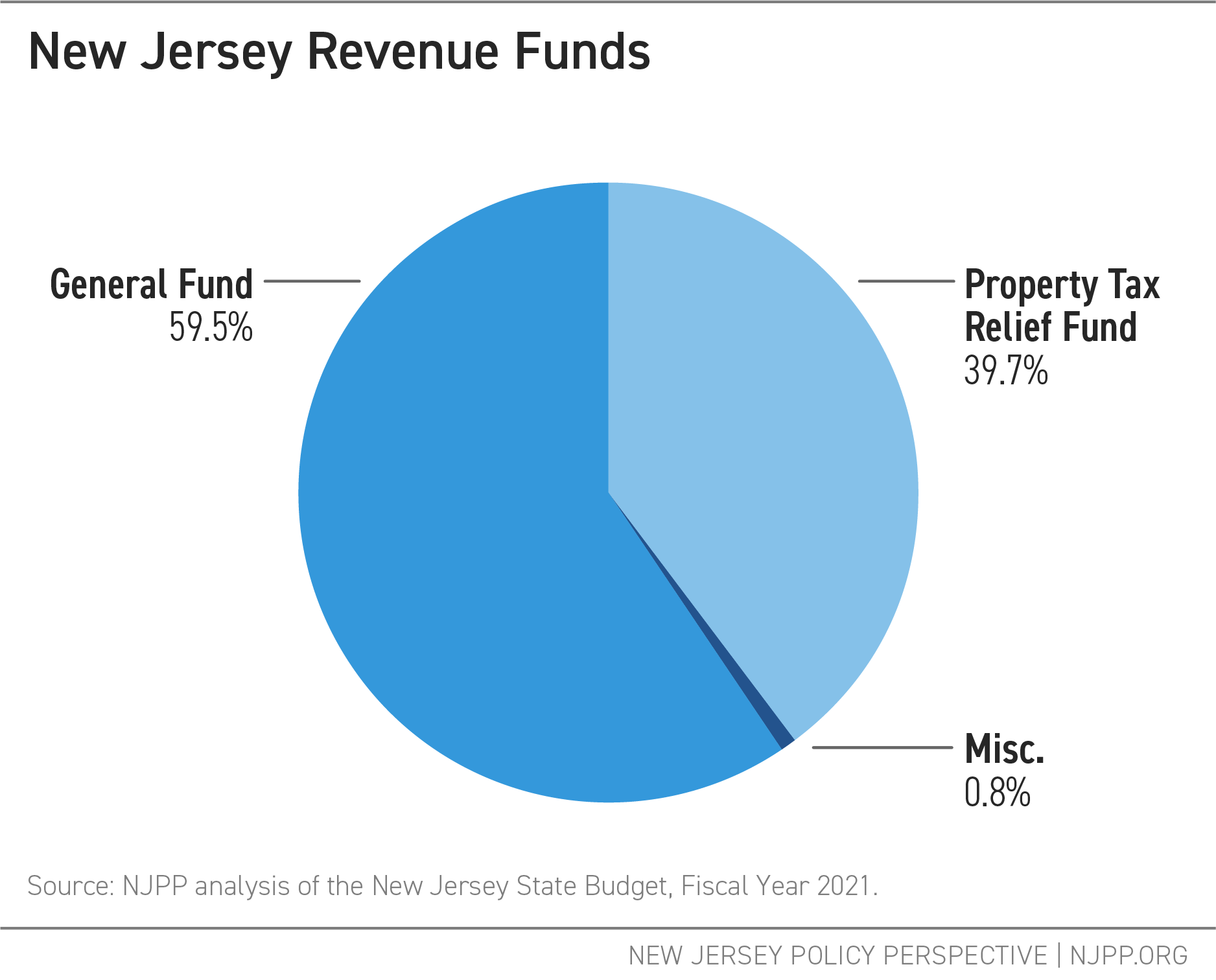

Tax contributions are placed into multiple funds that New Jersey draws on to finance the necessities outlined above. Of these, the General Fund and the Property Tax Relief Fund are the largest and most important.

The General Fund is where all state revenues not restricted by statute, or not dedicated to specific areas of the budget, are deposited and from which most appropriations are made. The revenues in the Property Tax Relief Fund, however, are dedicated to reducing or offsetting property taxes. The chart below illustrates the actual revenue that was generated and deposited into the General Fund in 2019.[xii]

The Property Tax Relief Fund is made up of revenue generated from the New Jersey Gross Income Tax and one half-cent of the Sales and Use Tax. This fund provides direct property tax relief through programs like the Senior Freeze and Homestead Rebate, as well as indirect relief by funding local school districts and essential services provided by local governments — investments that would otherwise be funded by property taxes.

Is There Enough Revenue to Meet New Jersey’s Needs?

Taken together, New Jersey generates approximately $40 billion in revenue every year. While that may be a large amount of money, the state budget has struggled to keep up with mere inflation over the last decade — due in part to some major tax cuts that benefitted wealthy individuals and big corporations. Because states are required to pass balanced budgets, meaning annual spending cannot exceed annual revenue collections, the state must bring in additional revenue to pay for its growing obligations, including programs that were chronically underfunded over the last thirty years.[xiii] Even without new programs, the state must ramp up spending over the next few years to fully fund public schools (in adherence to the School Funding Reform Act) and make full annual pension contributions, which were routinely skipped under previous administrations. The state must also raise enough revenue to build up a healthy surplus and Rainy Day Fund to protect against future economic downturns. New Jersey currently has one of the lowest Rainy Day Funds in the nation as the reserves were never replenished after the Great Recession.

New Jersey needs new, fairer ways to raise revenue to both meet its existing obligations and make new investments that benefit our communities. By making the tax code fairer, New Jersey can create a healthy and vibrant place to live for everyone that calls New Jersey home.

How Does the Budget Become Law?

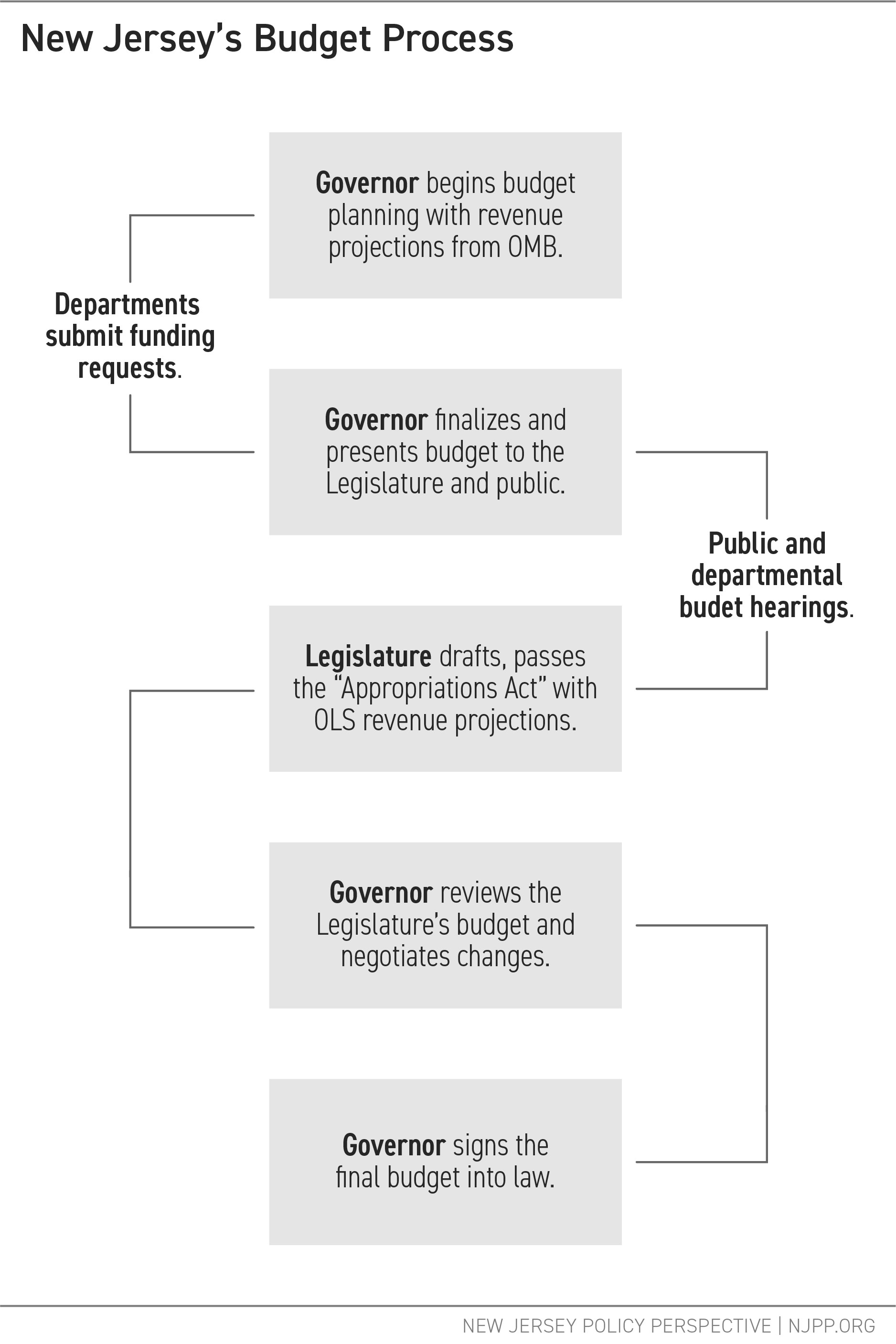

In New Jersey, the fiscal year runs from July 1st to June 30th of every year, but the budget process extends across many months and includes lots of different stakeholders — from the Legislature, to the Governor, to the leaders of state departments and agencies, to members of the public like you! Given the size and significance of the budget, it should be no surprise that the process is long and sometimes complicated. Let’s break it down.

What is the Budget Timeline?

The budget process is a nearly year-round affair.

September – January: It starts with the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), which manages the state’s financial assets, assessing the economy and making predictions about how much revenue is likely to be generated in the following year. With input from state agencies, they also make predictions about how much revenue will be needed to fund existing programs and departments.

January – February: With the projections from the OMB and requests for funding made by various departments, the governor prepares and presents a budget proposal to the Legislature and the public through the annual budget address, which takes place on or before the fourth Tuesday in February.[xiv] The governor’s address is what’s colloquially known as the start of “budget season” in Trenton.

February – May: Like OMB, the Office of Legislative Services (OLS) produces its own revenue projections, which the Legislature uses to craft their own budget or, as is often the case, make adjustments to the governor’s budget proposal. All the while, they hold extensive committee hearings for state agencies and the general public about their budget priorities. This part of the process begins after the governor’s budget address and generally runs through May.

June: The Legislature drafts and releases its own budget proposal, known as the Appropriations Act, which must be approved with a majority vote by both the Assembly and the Senate.[xv] Finally, the bill goes before the governor to be signed before the June 30th deadline.[xvi]

What is the Role of the Governor?

The governor of New Jersey enjoys an incredible amount of power and leverage in the budget process. Through the budget address, the governor sets the tone and priorities for the budget process. The governor’s initial budget proposal is also often used as the foundation for the Legislature’s budget bill. The governor also determines how much revenue is ultimately needed to balance the budget — which has big implications on tax policy — as the executive branch has the sole power to certify revenue estimates. And because the governor appoints the state Treasurer (as well as every other department head) the governor can influence both revenue projections and how much departments and agencies request in funding.

Once the Legislature passes their own budget proposal, the governor has four options:

- Sign the proposal, as is, into law.

- Reject the entire budget proposal outright and send it back to the Legislature.[xvii]

- “Line-item veto” certain spending priorities before signing the budget into law.

- If revenue projections from the OMB and the OLS are far enough apart, the governor may accept the budget as is and put some funding into a lockbox to be released later in the year if enough revenue is collected to cover those investments.

After the budget is signed into law, the governor also has the power to change the budget through Executive Orders. Nothing can be added to the budget, however, without approval from the Legislature.

What is the Role of the Legislature?

Once the governor releases a full budget proposal, the Legislature gets to work crafting their own bill with their own spending and revenue priorities. While the Legislature can choose to accept the governor’s budget in its entirety, this is unlikely. What often happens is that the Legislature writes their own budget and then negotiates a final deal with the governor.

Each house, the Senate and General Assembly, has their own budget committee that holds budget hearings throughout the Spring. Each committee has their own chairperson who wields power over their respective house’s budget process, but the Senate President and the Speaker of the Assembly ultimately act as the final gatekeepers for what is included in or excluded from the budget. The committees are responsible for hearing testimony from the public and all the state department heads. All of these hearings are also open to the public to attend.

After the budget becomes law, the Legislature has the power to change it by drafting and approving new bills to allocate funding for a particular program or service. This bill would have to follow the same process as the Appropriations Act and be signed into law by the governor.

If the governor vetoes a bill or performs a line-item veto, the Legislature has the power to override the veto with a two-thirds majority of all members of both the General Assembly and Senate.[xviii]

How Can Members of the Public Participate in the Budget Process?

Active participation in the budget process can really make a difference. Advocates and members of the public alike can and should share their priorities with the governor’s office and members of the Legislature both before and during the formal budget process.

While the governor is preparing the budget proposal, residents can contact the governor’s office to voice support for specific programs or initiatives that rely on state funding. You can also contact the governor’s office later in the budget process to voice your opinion in support of or opposition to potential programs at risk of being cut or line-item vetoed.

During the Legislature’s budget hearings, one of the best ways for residents to ensure their voices are heard is to testify at one of three public hearings offered by the Senate and Assembly budget committees. These hearings are often held across the state, with one meeting in each region of New Jersey: North, Central, and South. Anyone who signs up to testify can give comments. Legislators are meant to represent the people and be responsive to community needs. Believe it or not, most legislators like to hear from their constituents. Giving the issues you care about a face by providing a personal account can make an impact.

Writing, calling, and emailing legislators, including your own representative as well as those serving on the budget committees, with concerns or questions regarding a particular program or initiative is another way to ensure your voice is heard.

During the month of June, legislators negotiate the final budget within their caucuses and with the governor’s office. This is the time when advocates are the most active, lobbying and otherwise engaging legislators and the general public. This is a great opportunity to tap into your local advocacy organizations and meet with legislators about items in the budget that are of concern to you!

Glossary of Terms |

||

|

Term |

Definition |

|

| Appropriation | A sum of money that is authorized by the Legislature for a specific expenditure for a single fiscal year. | |

| Appropriations Act | The bill passed by the New Jersey Legislature that ultimately becomes the state’s annual budget. The budget becomes law when the Appropriations Act is signed by the Governor. | |

| Corporate Business Tax (CBT) | A tax on the net income or capital of a corporation. There are different rates for C and S Corporations. | |

| Earmark | Designated funds or resources for a particular purpose. | |

| Expenditure | Money owed, whether paid or unpaid. | |

| Fiscal Year | The twelve-month period to which the annual budget applies. New Jersey has a July 1 to June 30 fiscal year. | |

| General Assembly | One of the two Houses that comprises the state Legislature. The General Assembly has 80 members, two elected from each legislative district, and is presided over by the Assembly Speaker. | |

| Line Item | Any single item for which an appropriation is provided in the Appropriations Act. | |

| Line-Item Veto | Applying only to bills containing an appropriation, this veto action allows the Governor to approve the bill but reduce or eliminate funding for specific items. | |

| Office of Legislative Services (OLS) | A non-partisan agency of the Legislature that provides professional support services, including analysis, research, bill drafting, and legal services. In addition, the office provides information about the Legislature to the public. | |

| Office of Management and Budget (OMB) | An agency of the Governor’s Office that manages New Jersey’s financial assets. With direction from the Governor, the annual budget is the responsibility of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). | |

| Senate | One of the two Houses that comprises the state Legislature. The Senate has 40 members, one elected from each legislative district, and is presided over by the Senate President. | |

| Senate President | The chief presiding officer of the Senate during legislative sessions. The Senate President appoints committee chairs and members of committees and commissions, refers bills and resolutions to reference committees, sets the agenda for session days, and supervises the administration of the day-to-day business of the Senate. | |

| Speaker of the General Assembly | The chief presiding officer of the General Assembly during legislative sessions. The Assembly Speaker appoints committee chairs and members of committees and commissions, refers bills and resolutions to reference committees, sets the agenda for session days, and supervises the administration of the day-to-day business of the General Assembly. | |

| Veto | An official action taken by the Governor to nullify or deny a legislative action. | |

End Notes

[i] State of New Jersey Department of Education. (2019). https://www.state.nj.us/education/data/fact.htm

[ii] Nelson, B. (2019, July 25). What N.J. colleges are growing (and shrinking) the most? NJ.com. Retrieved 2020, from https://www.nj.com/data/2019/07/what-nj-colleges-are-growing-and-shrinking-the-most.html

[iii] https://www.state.nj.us/csc/about/publications/workforce/pdf/2018%20Workforce%20Profile%20final%20copy.pdf

[iv] In NJ, TANF is also called “Work First New Jersey.”

[v] Some of the agencies that are separate have been combined in this chart in order to make it easier to digest.

[vi] Nj.gov: https://www.nj.gov/treasury/omb/publications/19citizensguide/citguide.pdf

[vii] Clark, Kakkar, & Marcus (2020, September). Here’s how much money every N.J. school district gets in state funding shakeup.https://www.nj.com/education/2020/02/heres-how-much-money-every-nj-school-district-gets-in-state-funding-shakeup.html

[viii] Sitrin (2020, September) Why New Jersey’s progressive school funding formula still isn’t working for some children. https://www.politico.com/states/new-jersey/story/2020/09/30/why-new-jerseys-progressive-school-funding-formula-still-isnt-working-for-some-children-1318599

[ix] Weber, M. (2019, September). New Jersey’s Teacher Workforce, 2019: Diversity Lags, Wage Gap Persists. https://www.njpp.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/NJ-Teacher-Workforce-2019-Full-Report.pdf

[x]This report highlights how schools suffer (and which schools) due to lack of investment: https://www.njpp.org/publications/blog-category/new-jerseys-school-re-openings-are-racially-unequal/

[xi] ALICE (Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed) Project, New Jersey (2020). https://www.unitedforalice.org/Attachments/AllReports/2020ALICEReport_NJ_FINAL.pdf

[xii] FY2019 is the most recent year for which there is actual revenue data. The data for more recent years are currently “estimated” revenues. Source: Office of Management and Budget: Summaries of Revenues, Expenditures, and Fund Balances.

[xiii] The archives containing all budget documents can be found on the OMB’s website. This is a summary of the funds from FY2010, indicating that the balance of the state funds is just under 30 billion.

[xiv] Some exceptions are made to this deadline: it can be superseded by legislation, and if it is a governor’s first term, there is an extended deadline of March 13th.

[xv] At least 21 votes in the Senate and 41 in the General Assembly

[xvi] More detailed and technical information about the state’s budget process: NJ OMB

[xvii] If a Governor vetoes a bill, the Legislature can override it by a vote of at least two-thirds of the members of each house.

[xviii] Here is a FAQ from the OMB that contains more technical information and links to all the budget publications released by the state.