On June 24, 2022 the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the constitutional right to abortion care, significantly scaling back access to reproductive health care across the country. This explainer breaks down the impact of that decision both nationally and here in New Jersey.[i]

- What does the Dobbs decision mean for abortion rights in the United States?

- Who will be most impacted by this decision?

- What does this decision mean for New Jersey’s abortion laws?

- Do New Jersey’s laws go far enough to guarantee access to abortion care?

- How can state lawmakers improve abortion access in New Jersey?

What does the Dobbs decision mean for abortion rights in the United States?

The U.S. Supreme Court’s 6-3 decision in the case of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization overturned the constitutional right to abortion as recognized for nearly 50 years since the landmark cases of Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey.[ii] With federal protection gone, the legality of abortion at all stages of pregnancy will now be decided by individual states, putting the futures and lives of millions of people and their families at risk.

The right to an abortion is essential to the health, safety, and well-being of individuals who are or can become pregnant. The radical decision by the conservative court turns a blind eye to the individual needs of people who are pregnant and the many reasons they may seek an abortion.

Who will be most impacted by this decision?

The Dobbs decision will most impact those who live in states that ban abortion and do not have the financial means or time to travel to states where abortion care remains legal. Those who seek abortion care disproportionately earn low wages and, due to the nation’s legacy of slavery and exclusionary policies, that means Black and brown residents face the greatest barriers to accessing reproductive health care. When those with low incomes receive the care they need, their future socioeconomic and health conditions improve.[iii] Yet, when they are denied care, the harm to their overall well-being and that of their children can last for decades.

What does this decision mean for New Jersey’s abortion laws?

Do New Jersey's laws go far enough to guarantee access to abortion care?

The short answer: No, not everyone can access abortion care in New Jersey because rights alone do not equal access to services. Barriers like cost or a lack of nearby providers can delay care and, in some cases, push it completely out of reach.[xi] Here is how these barriers play out in New Jersey.

Insurance Coverage and Affordability

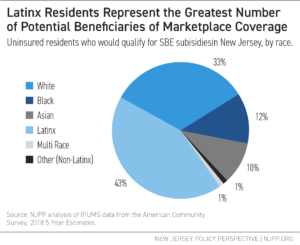

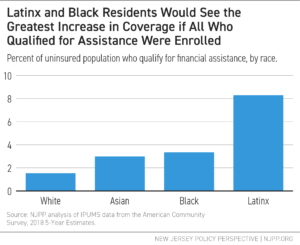

Cost remains one of the biggest barriers for people seeking health care in New Jersey. Nearly 700,000 New Jersey residents do not have insurance coverage and must rely on non-profit funding sources or state-run programs to cover the cost of any care they need.[xii] This includes over 480,000 people of reproductive age (19-54 years old).[xiii] Nearly 100,000 of New Jersey’s uninsured residents identify as Black and over 325,000 identify as Hispanic/Latinx.[xiv] This disparity in insurance coverage means health care cost barriers disproportionately harm Black and Hispanic/Latinx communities and worsen already inequitable maternal health outcomes.[xv]

Even those who have insurance coverage may not be able to afford the procedure due to high out-of-pocket costs, such as copays. Health insurance plans can include high deductibles — the amount a person must pay out of pocket before services are covered — and high copays (flat rates for covered services) or coinsurance (a set percentage that a person pays for a covered service). Plans can also differ by employer or provider and can change year to year, creating confusion amongst residents about what their plan may cover.

Finally, the cost of an abortion depends on the pregnancy.[xvi] An abortion in the first trimester may cost a few hundred dollars or a few thousand dollars if the patient requires a hospital procedure due to pre-existing conditions. An abortion in the second trimester costs significantly more, as some procedures can cost more than $5,000.[xvii] This means that if someone is unable to access care early in their pregnancy due to cost barriers, geographic and time constraints, or because they didn’t know they were pregnant, they may face a higher bill than someone who learned about the pregnancy early and secured an appointment without delay.

Geographic Proximity

The location of available abortion providers can also impede access to care. Roughly one third of New Jersey counties — home to more than a quarter of all New Jersey women — do not have an abortion provider, meaning that more than one in four women do not have access to an abortion provider close to home.[xviii] And this is likely an undercount since available data does not represent an accurate count of people who can become pregnant, including transgender and nonbinary individuals.

At a time when the availability of maternal services in counties is in danger — exemplified by the recent closing of Cape May County’s only maternity ward — the limited availability of abortion providers puts many New Jersey residents and their families at an unfair disadvantage with lifelong consequences.[xix] Like other types of health care, and particularly care that can be urgent, the lack of nearby providers remains a key barrier to timely, quality care.

Immigration Status

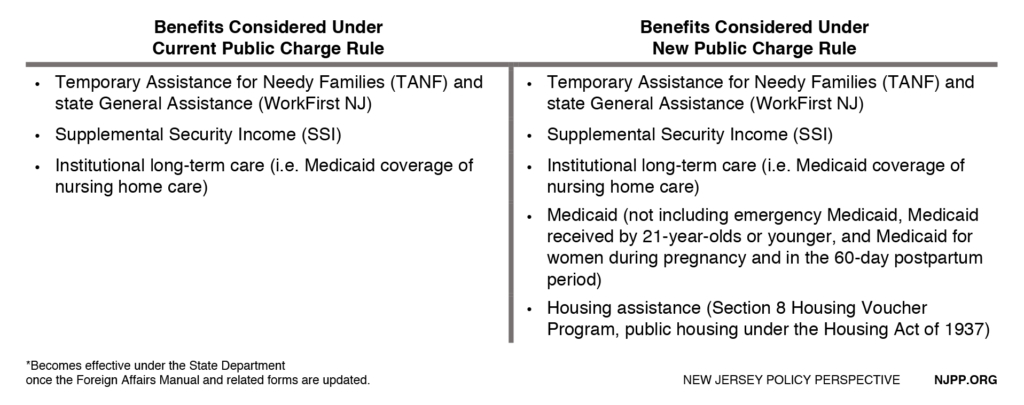

Abortion access, like other aspects of health care, is severely limited by restrictions on health insurance coverage due to immigration status. Rules that restrict which immigrants can access health insurance plans through health care marketplaces like GetCoveredNJ and state- and federally-run programs like Medicaid mean that many immigrant families do not qualify to enroll in coverage and struggle to find affordable insurance through private plans. Legal Permanent Residents are barred from enrolling in Medicaid for five years.[xx] Undocumented immigrants are barred from all programs except where the state has set up its own funding.[xxi] This lack of options forces individuals and families to pay for care with their own savings—which are often limited due to low-paying jobs. Without an expansion of affordable options, immigrant families will continue to be left behind.

How can state lawmakers improve abortion access in New Jersey?

Improving abortion access requires policies to ensure that everyone, regardless of immigration status, insurance status, gender, income, age, or location has access to reproductive health care when needed. Here are three top policy changes that would improve abortion access in New Jersey right now, many of which are included in a bill (S2918/A4350) introduced in June 2022 to improve equitable access to abortion care.[xxii]

Guarantee insurance coverage of abortion with no copays

New Jersey's Medicaid program, NJ FamilyCare, covers abortion without any out-of-pocket costs. But for private insurance plans, coverage of abortion care is not mandated.[xxiii] This means that access to this essential care not only relies on having insurance but on whether an employer or program has chosen to include abortion care in their health plan.

New Jersey can step up its role as a national leader in reproductive rights by mandating coverage in all state-regulated private plans and prohibiting cost-sharing for abortions. This is not a new concept: Seven states mandate coverage of abortion in all private insurance plans, including plans on their state health insurance marketplaces.[xxiv] As of January 1, 2023, all seven states outside of New Jersey that mandate abortion coverage (California, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, New York, Oregon, and Washington) will also all prohibit cost-sharing (deductibles, copays, or coinsurance), to make sure that, even when covered, the service remains affordable to the patient.[xxv] Following these states’ examples will help to ensure equitable access to coverage.

Secure funding for those who are uninsured or underinsured

The ability to access affordable reproductive care, including abortion, should not rely on a health care system that allows gaps persistent in coverage. Thousands of New Jerseyans, including undocumented immigrants and part-time workers who do not qualify for benefits, struggle to find quality, affordable coverage. And we know that without coverage, paying out of pocket is often untenable, putting health care, including time-sensitive abortion care, out of reach.

Mutual aid groups and non-profit entities, like the New Jersey Abortion Access Fund, can help, but these resouces can’t be expected to fill the access gaps alone. The state must take on a more defined role. Financial assistance for prenatal care and contraception is currently available for those who are uninsured, including undocumented immigrants, through the New Jersey Supplemental Prenatal and Contraceptive Program (NJSPCP).[xxvi] However, this program does not cover abortion care, nor is it codified in state law, leaving it vulnerable to cuts under a different administration in the future.

New Jesey can do three things to guarantee greater equity in abortion access: Expand services of NJSPCP to include abortion care, expand eligibility of NJSPCP to allow underinsured residents to access the program, and enshrine into statute the expanded program to codify these protections.

Expand services across the state so geographic proximity does not limit access to services

The state can do more to help support the availability of reproductive health services and providers across the state.[xxvii] The New Jersey Board of Medical Examiners rule change expanding which medical professionals can now perform abortion services will certainly help to grow the provider pool. However, the policy change must be codified into state law to protect this new class of providers from a future administration that could potentially be hostile to reproductive rights. The state should also commit to sustained support of family planning services (such as birth control, cancer screenings, and testing and treatment for sexually transmitted infections and HIV) and grants to help close remaining access gaps in counties without a single abortion care provider.

End Notes

[i] Many thanks to the teams at ACLU of New Jersey, Cherry Hill Women’s Center, and Planned Parenthood of Northern, Central and Southern New Jersey, Inc. for their helpful feedback in the preparation of this explainer!

[ii] Supreme Court of the United States, Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 2022, Docket No. 19-1392. Documents available at: https://www.supremecourt.gov/search.aspx?filename=/docket/docketfiles/html/public/19-1392.html

[iii] Guttmacher Institute, Induced Abortion in the United States, 2019. https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/induced-abortion-united-states; Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health (ANSIRH) at University of California - San Francisco, The Turnaway Study, 2020. https://www.ansirh.org/research/ongoing/turnaway-study

[iv] New Jersey Supreme Court, Right to Choose v. Byrne, 91 N.J. 287, 1982, Justia. https://law.justia.com/cases/new-jersey/supreme-court/1982/91-n-j-287-0.html

[v] UCLA Obstetrics and Gynecology, Medical versus Surgical Abortion, 2022. https://www.uclahealth.org/obgyn/medical-versus-surgical-abortion; New Jersey Monitor, Murphy signs law solidifying abortion rights in New Jersey, 2022. https://newjerseymonitor.com/2022/01/13/murphy-signs-law-solidifying-abortion-rights-in-new-jersey/;

[vi] Office of Governor Phil Murphy, New Jersey Expands Access to Reproductive Health Care, Adopts New Rules from Unanimous Vote by State Board of Medical Examiners, 2021. https://www.nj.gov/governor/news/news/562021/20211206a.shtml

[vii] New Jersey Monitor, State board expands access to abortion in N.J. through regulation changes, 2021. https://newjerseymonitor.com/briefs/state-board-expands-access-to-abortion-in-n-j-through-regulation-changes/

[viii] Office of Governor Phil Murphy, Governor Murphy Signs Legislation to Protect Reproductive Health Care Providers and Out-of-State Residents Seeking Reproductive Services in New Jersey, 2022. https://www.nj.gov/governor/news/news/562022/20220701a.shtml

[ix] New Jersey Office of the Attorney General, Acting AG Platkin Establishes Reproductive Rights Strike Force” to Protect Access to Abortion Care for New Jerseyans and Residents of Other States, 2022. https://www.njoag.gov/acting-ag-platkin-establishes-reproductive-rights-strike-force-to-protect-access-to-abortion-care-for-new-jerseyans-and-residents-of-other-states/

[x] New Jersey Policy Perspective, Affordable for Some: What’s Included and Missing in New Jersey’s FY 2023 Budget, 2022. https://www.njpp.org/publications/blog-category/affordable-for-some-whats-included-and-missing-in-new-jerseys-fy-2023-budget/

[xi] Guttmacher Institute, Induced Abortion in the United States, 2019. https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/induced-abortion-united-states; Kaiser Family Foundation, Abortions Later in Pregnancy, 2019. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/fact-sheet/abortions-later-in-pregnancy/

[xii] NJPP Analysis of American Community Survey Data, 2020 5-Year Estimates. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=health%20insurance&g=0400000US34&tid=ACSST5Y2020.S2701

[xiii] Generally, medical definitions of reproductive age range from 12 or 15 years old to 49 or 51 years old for women. Because the Census does not provide further breakdown, the above estimate provided the closest groupings available.

[xiv] NJPP Analysis of American Community Survey Data, 2020 5-Year Estimates. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=health%20insurance&g=0400000US34&tid=ACSST5Y2020.S2701

[xv] NJ Spotlight News, Access to abortion is an uphill battle for some in New Jersey, 2022. https://www.njspotlightnews.org/2022/07/nj-abortion-access-obstacles-state-law-supreme-court-roe-overturned/; NJ Spotlight News, Advocates fear Roe v. Wade ruling will impact Black women most, 2022. https://www.njspotlightnews.org/2022/06/us-supreme-court-roe-v-wade-nj-fear-racial-inequities-black-women-people-of-color/

[xvi] Health Affairs, Trends In Self-Pay Charges And Insurance Acceptance For Abortion In The United States, 2017–20, 2022. https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01528

[xvii] Range of costs determined through discussions with abortion providers in New Jersey.

[xviii] Guttmacher Institute, Abortion Incidence and Service Availability in the United States, 2017, 2019. https://www.guttmacher.org/report/abortion-incidence-service-availability-us-2017

[xix] The Press of Atlantic City, Come September, maternity services will no longer be offered at Cape Regional Medical Center, 2022. https://pressofatlanticcity.com/news/local/come-september-maternity-services-will-no-longer-be-offered-at-cape-regional-medical-center/article_9abcc3f8-09f8-11ed-8493-57a5151d95a7.html; Additionally, across the country, there have been concerns about the impact of the growth and consolidation of Catholic health care systems which may limit access to care: https://apnews.com/article/abortion-health-religion-new-york-oregon-8994d9b5fd0040d40d19fd1e44c313d8

[xx] New Jersey Department of Human Services, NJ FamilyCare - Immigrant Information, 2022. http://www.njfamilycare.org/imm_info.aspx

[xxi] One example of a state-funded program in New Jersey is the Cover All Kids program, which will open up NJ FamilyCare to all kids under the age of 19, regardless of immigration status, starting in January 2023.

[xxii] New Jersey Legislature, S2918/A4350: Strengthens access to reproductive health care; appropriates $20 million, 2022. https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/bill-search/2022/S2918; Thrive New Jersey, Abortion Access, 2022. https://www.thrive-nj.com/rfa

[xxiii] Rutgers Today, What Does Overturning Roe v. Wade Mean for New Jersey?, 2022. https://www.rutgers.edu/news/how-far-does-new-freedom-reproductive-choice-act-go-keep-abortion-legal-new-jersey

[xxiv] Guttmacher Institute, Regulating Insurance Coverage of Abortion, 2022. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/regulating-insurance-coverage-abortion

[xxv] Guttmacher Institute, Regulating Insurance Coverage of Abortion, 2022. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/regulating-insurance-coverage-abortion; Office of Governor Gavin Newsom, Governor Newsom Signs Legislation to Eliminate Out-of-Pocket Costs for Abortion Services, 2022. https://www.gov.ca.gov/2022/03/22/governor-newsom-signs-legislation-to-eliminate-out-of-pocket-costs-for-abortion-services/; New York, Protecting & Strengthening Abortion Rights, 2022. https://www.ny.gov/abortion-new-york-state-know-your-rights/protecting-strengthening-abortion-rights

[xxvi] New Jersey Abortion Access Fund, About Us, 2022. http://njaaf.weebly.com/; New Jersey Department of Human Services - NJ FamilyCare, New Jersey Supplemental Prenatal and Contraceptive Program (NJSPCP), 2022. http://www.njfamilycare.org/njspcp.aspx

[xxvii] Recent reporting has discussed the need for OB/GYNs in New Jersey, particularly in certain areas. See: NJ.com, A Shortage of OB-GYNs Looms. Why are They Fleeing N.J.?, 2022. https://www.nj.com/healthfit/2022/11/why-are-ob-gyns-fleeing-nj-a-shortage-looms-on-the-near-horizon.html. It’s important to note that, as a state, New Jersey has a higher number of OB/GYNs than many other states (see Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Employment and Wages, 29-1218 Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2021. https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291218.htm). Yet, finding ways to improve access to care should always be prioritized. OB/GYNs are one type of reproductive health care provider who can play a key role in access to abortion. As noted above, the Board of Medical Examiners rule change expands the types of providers able to provide their full scope of care, including abortion. This rule change helps to address one path to access. Ensuring all types of providers and their services are available across the state will be important for building more equitable access to care.