New Jersey is a rich state with high median wages, high concentrations of wealth, and high productivity.[i] But that wealth does not translate into prosperity for all — more than 1 in 8 children live in poverty,[ii] and key public investments, including schools, public transportation, and municipal services, have faced decades of underfunding and underinvestment. The top 1 percent of households by income take home more than 24 times more than the bottom 99 percent.[iii] Meanwhile, economic growth is increasingly concentrated in multinational corporate profits instead of workers, deepening a system of haves and have-nots.[iv] This inequality exacerbates racial economic divides, with Black and Hispanic/Latinx workers paid lower wages and holding less wealth than white households.[v]

New Jersey can counter these trends, sustain public investments, and reduce income concentration in wealthy households and corporations, by strengthening its progressive tax system. In this system, wealthier individuals pay a higher tax rate, while those with lower incomes pay less.[vi] This approach reflects societal values that those who have benefited the most from our economic systems should contribute a higher percentage of their income and pay back their fair share to the rest of the state, while those with fewer financial resources should pay a smaller share.

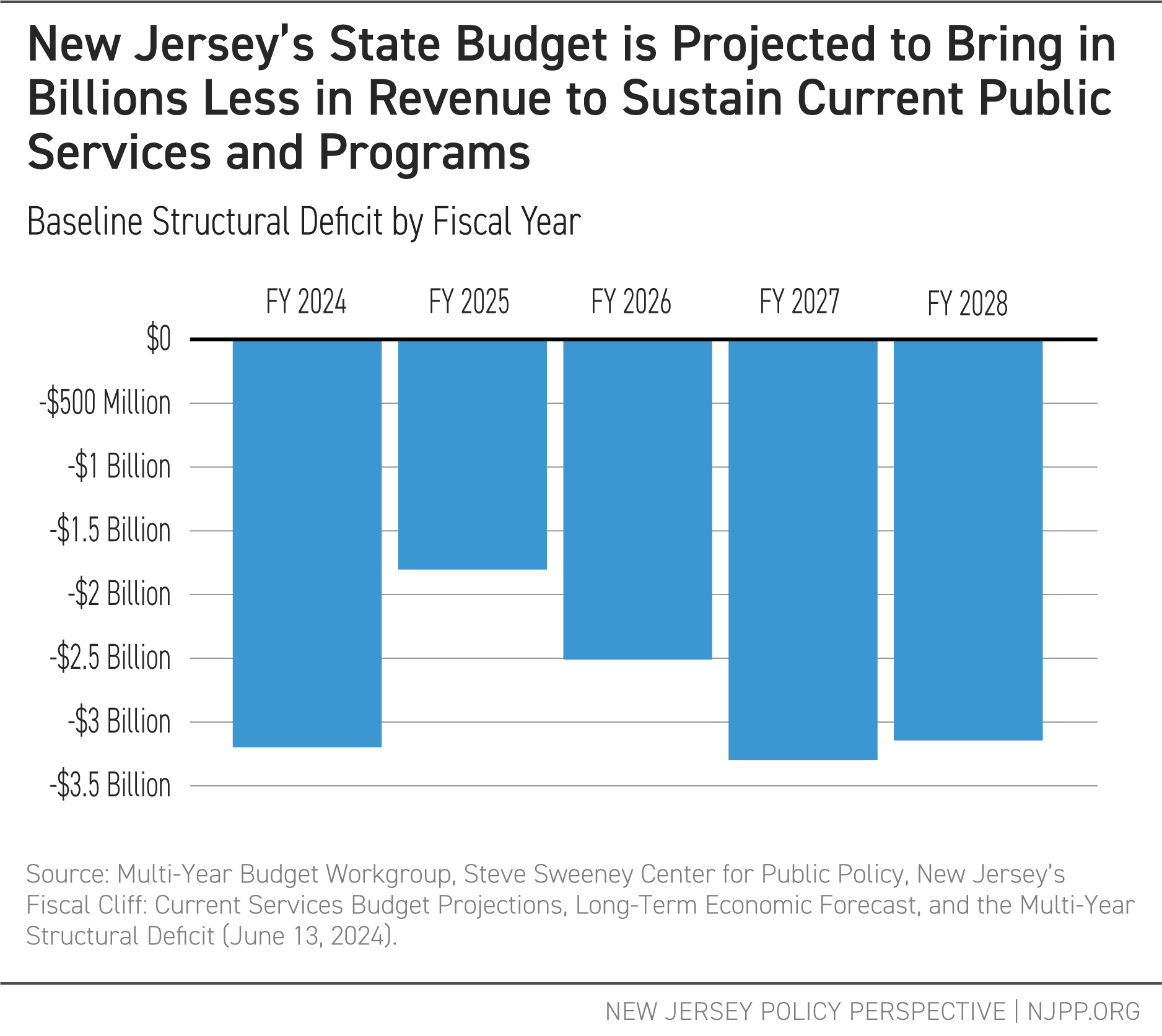

Now is the moment to address tax fairness, as more revenue will be needed to improve affordability for the state’s residents. Unfortunately, the state’s revenues have not kept pace with existing obligations, in part because of years of underinvestment in pensions, deferred maintenance on New Jersey Transit,[vii] and failure to fully fund the school funding formula.[viii] These choices led to irresponsible budgeting, which mortgaged the state’s future for short-term budget patches.[ix] As a result, the state is now running a structural deficit, meaning it collects less in revenue than it spends on programs and services.[x] As these longer-term fiscal projections from an independent group of New Jersey budget experts show in the graph below, this deficit will expand in the years to come, draining the state’s surplus and hampering new investments.[xi]

New Jersey’s need for tax reform has additional urgency because of looming threats to the national landscape. Federal tax law changes from 2017 gave substantial tax cuts to wealthy individuals and corporations starting in 2019, but those changes may become permanent in 2025 when those provisions expire.[xii] Expiring federal funds from pandemic-era aid for states will create fiscal cliffs for critical programs such as New Jersey Transit, which has already led to fare increases and the end of popular fare programs.[xiii] The state’s economy needs increased investment in public services at exactly the time when federal support for progressive tax policy and aid to states is declining.

To meet these policy goals, this report lays out a range of revenue-raising options that meet key criteria:

- Raise new revenues for the state

- Are based on former or current tax systems such as gross income, sales, or corporate taxation

- Increase the overall progressivity of the state’s tax system

- Improve racial and economic equity by closing existing income and wealth disparities.

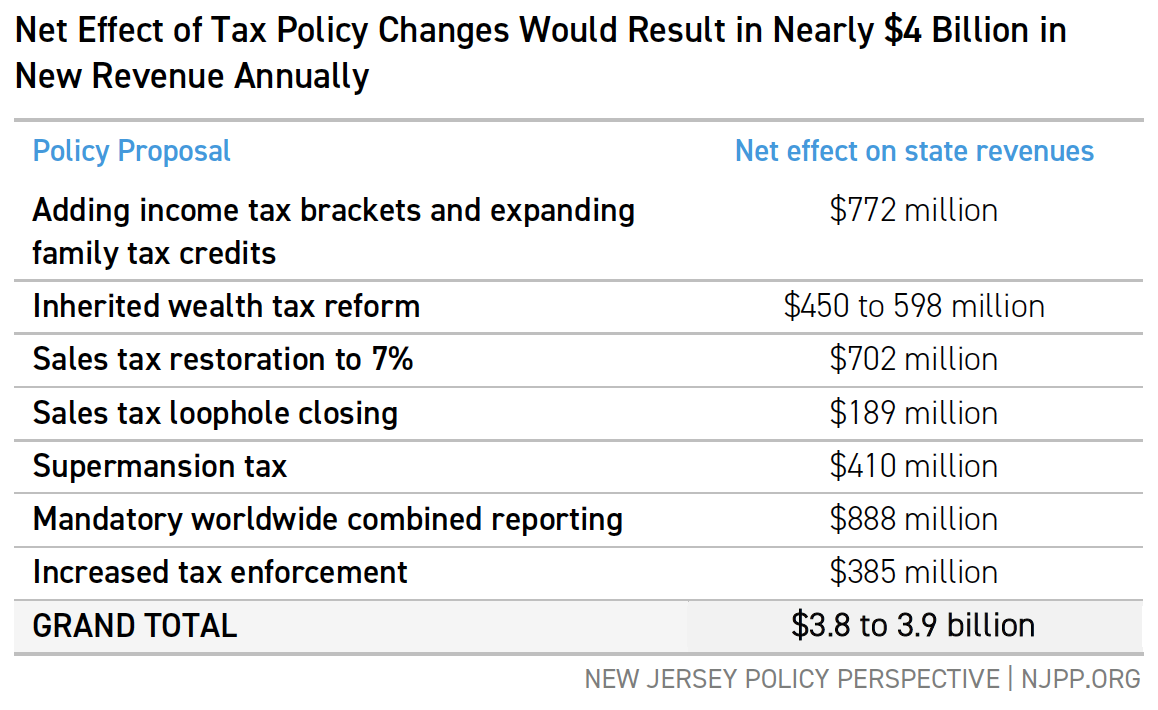

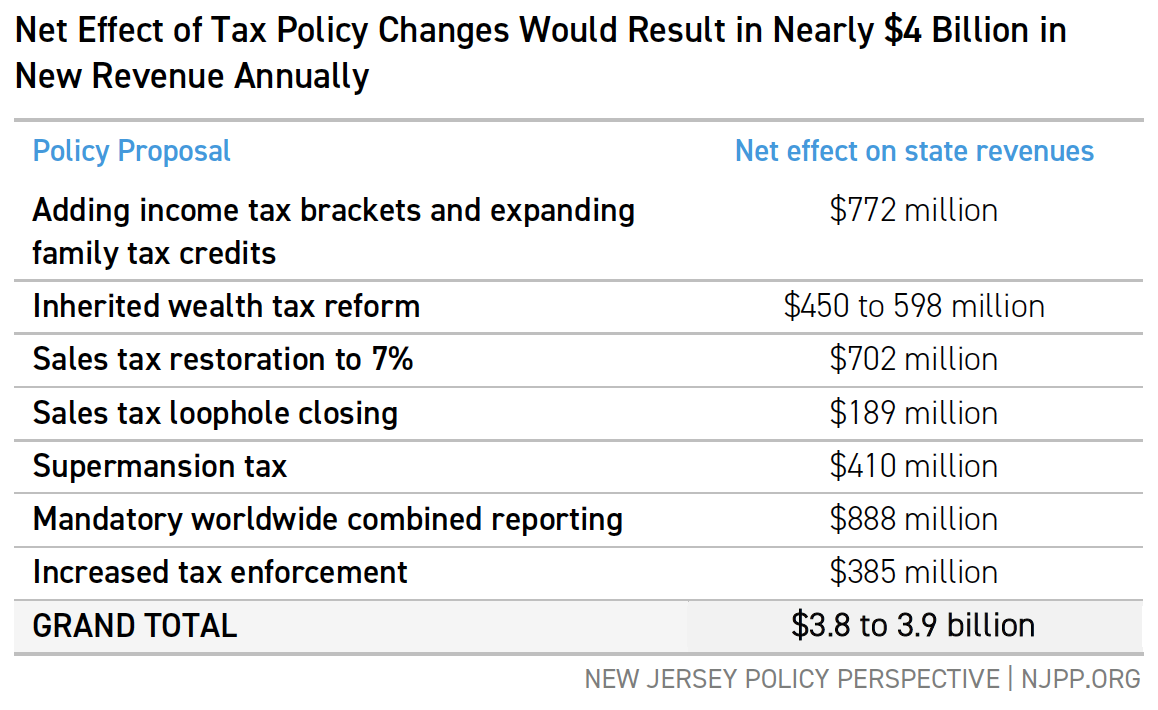

The full package of revenue increases outlined in this report would raise nearly $4 billion annually for the state’s budget — enough to make all school meals free, restore state aid to schools getting cuts, and cover the state’s entire deficit. The full package includes the state’s major revenue streams, including gross income, sales, corporate business, and inherited wealth taxes, identifying targeted changes to generate much-needed funding without placing those costs disproportionately on the people who need the most help:

- Income tax: Revising the income tax to add brackets for higher-income residents, including new rates on earners over $2 million, $5 million, and $10 million in income, while expanding working-family tax credits such as the Child Tax Credit and Earned Income Tax Credit to ensure that low- and moderate-income households benefit from the tax changes.

- Inherited wealth tax: Reforming inherited wealth taxes to reduce unearned wealth transfers and tax large inheritances.

- Sales tax: Restoring the sales tax to 7 percent, along with modernizing services exemptions, which have excluded accounting, advertising, engineering, and other high-end services from taxation.

- Realty transfer fee: Adding two percentage points to the existing 1 percent realty transfer fee on home sales over $1 million and four percentage points on sales over $2 million.

- Corporate tax: Requiring large multinational corporations to report profits from overseas subsidiaries, forcing them to stop offshore profit-shifting.

Right-Size the Income Tax: Raise Rates at the Top, Lower Them at the Bottom

Right-Size the Income Tax: Raise Rates at the Top, Lower Them at the Bottom

Proposal Overview

Making New Jersey’s income tax more progressive would increase revenue and improve affordability for working- and middle-class households. This proposal would add new tax brackets for incomes over $2 million, $5 million, and $10 million, affecting only a tiny fraction of taxpayers but targeting a significant portion of the state’s wealth. Additionally, it would expand the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) to 50 percent of the federal credit and make all workers who file taxes eligible to claim it. The Child Tax Credit (CTC) would also be expanded to $1,500, extending eligibility to children up to age 11. While the expanded working-family tax credits would reduce overall revenues, they would reduce income inequality and provide more financial support to low- and moderate-income households. Combined, this proposal would generate about $772 million annually.[xiv]

Raise Rates at the Top: Higher Marginal Income Tax Rates for High Earners

New Jersey’s gross income tax applies different rates to income brackets, starting at 1.4 percent for the first $20,000 and reaching 10.75 percent for income over $1 million. This tax funds the state’s local property tax relief and serves as the primary revenue source for school aid.[xv] Even with these progressive elements, wealth continues to remain heavily concentrated in high-income households, with the top 20 percent of households taking home more than half the state’s total income.[xvi]

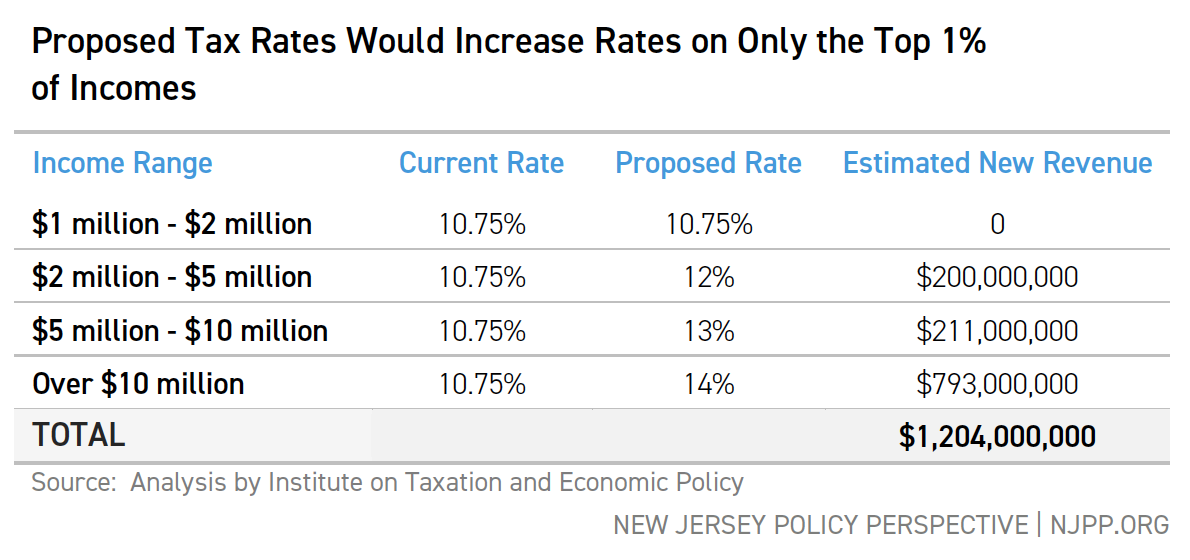

As shown in the table below, the proposal introduces new tax brackets at $2 million, $5 million, and $10 million, in addition to the existing 10.75 percent rate on earnings over $1 million, known as the “Millionaires Tax.” This adjustment alone would raise more than $1.2 billion for essential state programs while affecting less than 1 percent of households.[xvii] As wealth continues to concentrate at the top, a fair tax system should impose higher rates on the highest earners.

As the state’s experience with the millionaires tax has shown, gross income tax receipts continue to climb despite the increasing marginal rates for those earning over $1 million and $5 million income.[xviii] Additionally, research shows that raising income tax rates on high earners has minimal impact on economic growth.[xix] High-income residents continue to call New Jersey home, and the number of tax filers with over $1 million in income increased by nearly 50 percent between 2019 and 2021.[xx]

Lower Rates at the Bottom: Expanding Working Family Tax Credits

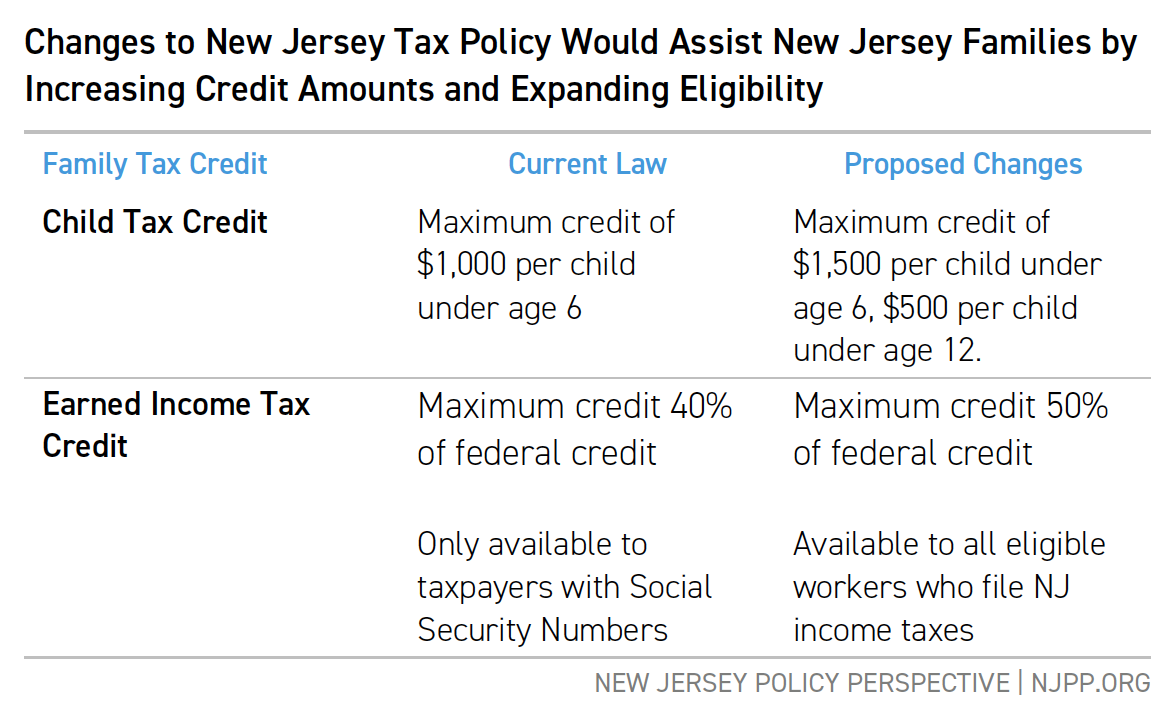

New Jersey, like many states, uses its tax code to reduce poverty and improve affordability to working families and households to help them meet the cost of living by putting cash directly into their bank accounts to help cover the cost of living in the state.[xxi] In particular, the state funds two major tax credits that reduce poverty statewide: the state Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC)[xxii] and the state Child Tax Credit (CTC).[xxiii] As the name implies, the EITC pays workers back by enhancing their incomes, while the CTC provides cash rebates to families with children under age 6. The success of the federal Child Tax Credit has shown that even modest increases in credit amounts can dramatically reduce child poverty.[xxiv]

However, in New Jersey, both programs are still limited in their eligibility, weakening their antipoverty effects. The EITC, for example, is not available for workers without a Social Security number, excluding immigrant workers who pay and file taxes each year.[xxv] The CTC is only available for families with a child under age 6,[xxvi] despite research showing that children’s expenses grow as they age.[xxvii]

New Jersey should expand its Earned Income Tax Credit to 50 percent of the federal credit, and expand eligibility to all workers who file taxes, not just those with Social Security numbers.

Similarly, New Jersey should expand its Child Tax Credit to children ages 6 to 11 and increase the maximum benefit from $1,000 to $1,500 for children under age 6.[xxviii]

These changes would put hundreds of dollars back into families’ pockets, helping make New Jersey the best place to raise a family. These combined proposals would increase the progressivity of the tax code by providing an estimated $432 million to low- and moderate-income households. By amplifying the antipoverty effects of these critical lifelines, the state can help more households meet basic needs and raise the standard of living for working families.

Net Effect of Combined Income Tax Proposals

Net Effect of Combined Income Tax Proposals

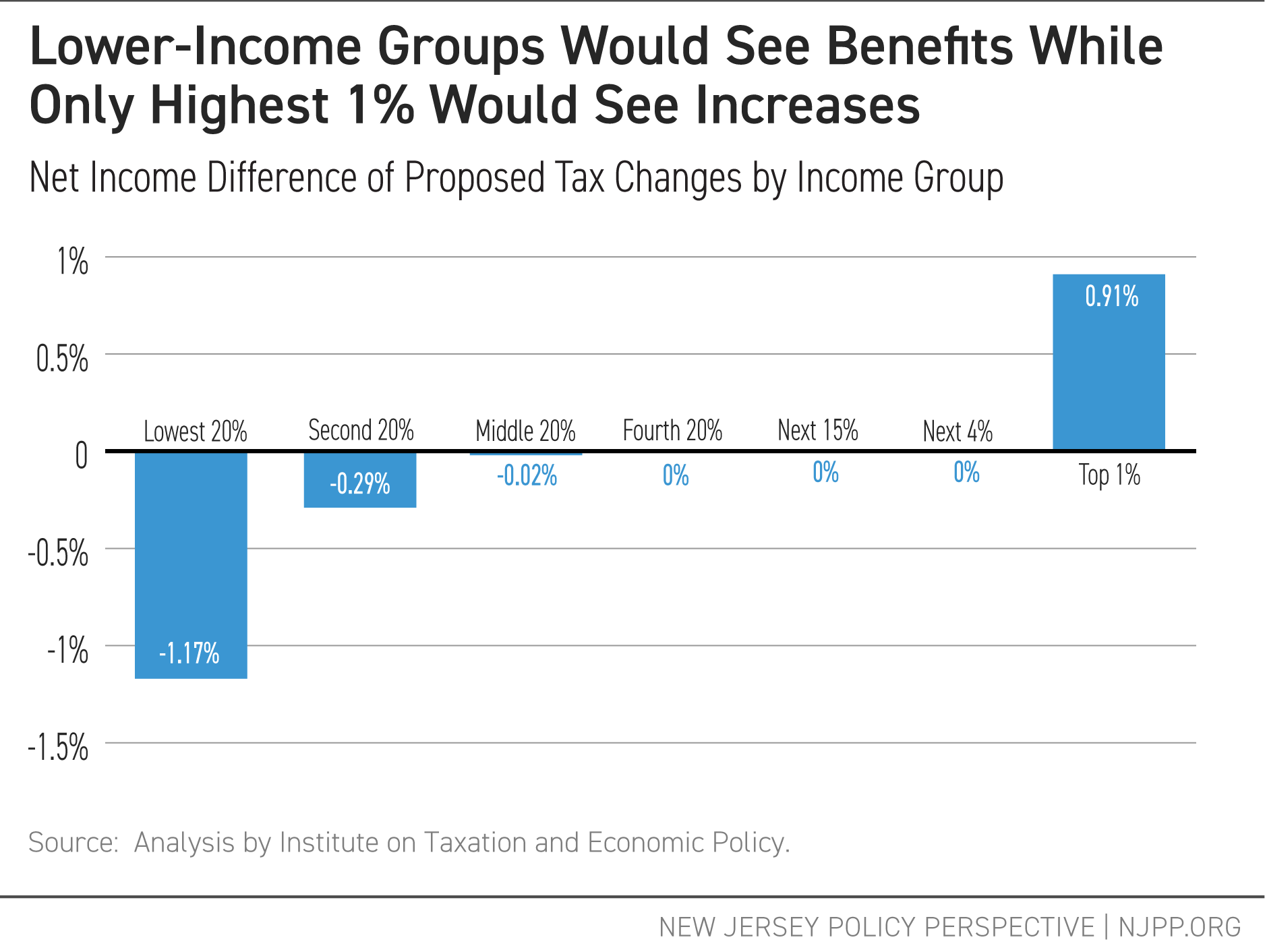

Expanding tax credits for the lowest 40 percent of earners while raising income tax rates for the top 1 percent would make the state’s income tax system more progressive. This would generate additional income for the state while reducing the financial burden on its lowest-income residents, with no changes to rates for the majority of taxpayers.

This combination of income tax changes would boost revenue and make the tax system fairer — a win-win for both New Jersey and its residents. The annual increase of $1.2 billion in revenue based on the bracket changes at the top of the income spectrum would be partially offset by the $432 million in reductions for low- and moderate-income households, resulting in a net revenue increase of $772 million. These tax law changes raise costs only for the wealthiest one percent while helping those who need the most help and funding critical state priorities.

Restore Taxes on Inherited Wealth Transfers

Proposal Overview

Taxation of intergenerational wealth is critical to reducing wealth inequality, shrinking the racial wealth gap, and equitably generating revenue. New Jersey currently has an inheritance tax which taxes the money collected by heirs, but the state no longer has an estate tax which taxes the overall value of the deceased person’s estate.[xxix] The proposed options aim to either eliminate inheritance tax exemptions or restore the estate tax, ensuring that intergenerational wealth transfers among the wealthiest households contribute to critical state needs. By implementing these changes, New Jersey could generate between $450 million and $598 million annually.[xxx]

Proposal Details

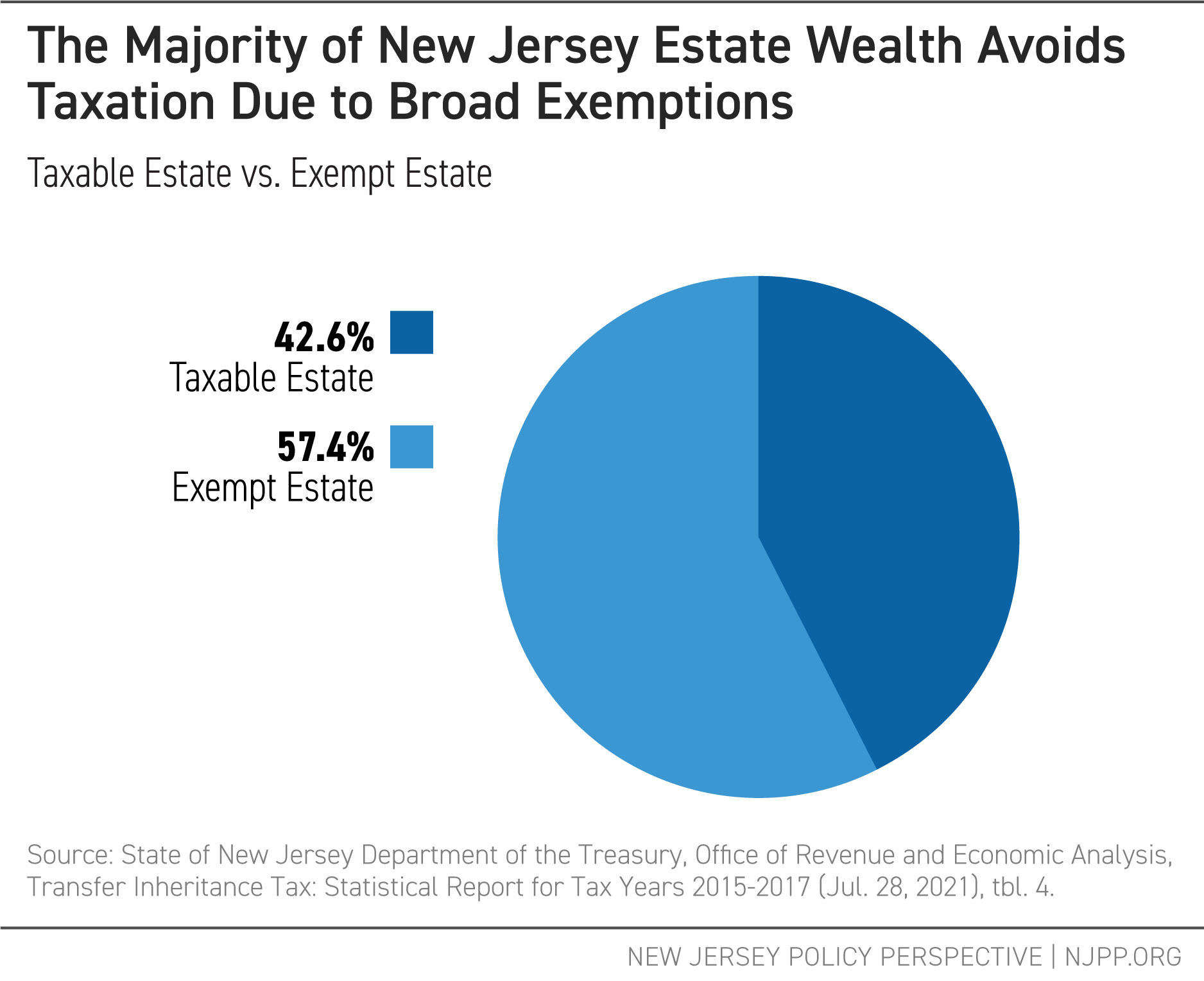

Currently, the inheritance tax includes major exemptions, covering lineal descendants (children, grandchildren, etc.), spouses, or lineal ancestors (parents, grandparents, etc.).[xxxi] Since the majority of inheritances come from parents or grandparents,[xxxii] these broad exemptions have resulted in most estate wealth being exempt from taxation entirely: Of the nearly $5.8 billion in total estate wealth in 2017, less than $2.5 billion (43 percent) was taxable.[xxxiii]

These loopholes run the risk of worsening wealth disparities and racial wealth inequality. Inheritances disproportionately benefit higher-income people, who compound their existing wealth while lower-income people are unlikely to receive any inheritance at all.[xxxiv] Across races, the difference in inheritance rates reinforce existing disparities: 30 percent of white families nationally report having received an inheritance, compared to only 10 percent of Black and 7 percent of Latinx/Hispanic families.[xxxv]

Compounding matters, New Jersey eliminated its estate tax for residents passing away after December 31, 2017.[xxxvi] Estate taxes were levied on the total value of the estate of the deceased person, and the elimination of this tax has led to substantial revenue loss for the state, estimated at $560 million in 2022 — $598 million in 2024 dollars.[xxxvii]

Concerns about the potential risks of inherited wealth taxes at the state level, such as forced home sales to cover tax costs or an exodus of older high-wealth residents, do not have a strong basis in the available evidence. Real estate such as homes and land do not make up the bulk of estates, which are overwhelmingly composed of intangible property such as retirement and bank accounts.[xxxviii] Meanwhile, research on aging adults and their moving behavior shows, at most, little effect on residence decisions.[xxxix]

New Jersey has two options for taxing inherited wealth transfers:

- Eliminating the inheritance tax exemptions and subjecting all transfers to taxation;

- Restoring the estate tax.

Removing inheritance tax exemptions would generate an estimated $451 million in annual revenue for the state[xl]. Restoring the estate tax could generate between $450 million and $598 million annually. These amounts could vary, depending on state policy decisions such as the size of exemptions, whether some heirs would still have partial exemptions, and the interplay between the two taxes. Nonetheless, taxing intergenerational wealth transfers is an effective way to raise revenue while reducing wealth inequality.

Restore the Sales Tax Rate and Eliminate Loopholes and Exemptions

Proposal Overview

Reversing the damaging Christie-era sales tax cut while modernizing the sales tax by eliminating gimmicks and exemptions would create a broader tax base and generate much-needed revenue. Specifically, the proposal aims to: restore the sales tax from 6.625 percent to 7 percent; eliminate loopholes for car rental companies and yacht purchases; and tax high-end professional services. Taken together, this proposal could generate about $859 million.

Restoring the sales tax to 7 percent would generate $702 million annually, while eliminating the car rental and yacht loopholes would add another $157 million. Estimates for eliminating high-end professional services vary due to the complexity of industry-specific sales data.

Proposal Details

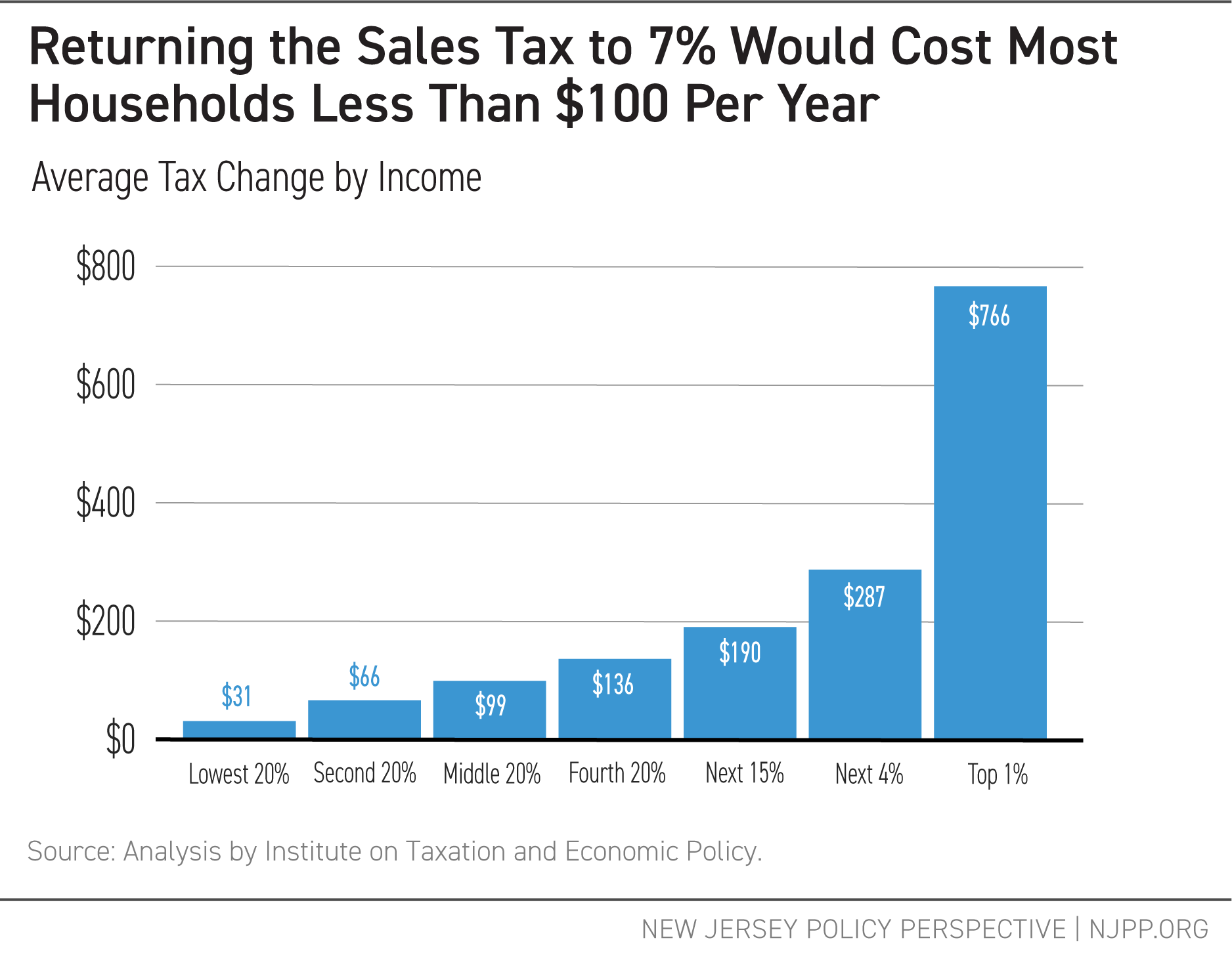

Increasing sales taxes can bring in much-needed reliable revenue for a budget facing a structural deficit.[xli] New Jersey’s sales tax supports the state’s general fund by taxing consumer purchases, with exemptions for groceries, medicine, and various services.[xlii] Although the sales tax does place proportionally more financial burden on lower-income residents, the below graph shows that people in the bottom 60 percent of incomes would see increases of under $100 if the sales tax cut were reversed, with even smaller amounts for lower-income residents.

To counter the impact on low- and moderate-income households, New Jersey can maintain and improve its overall progressive tax code by expanding refundable working family tax credits as detailed in the income tax section above.[xliii]

Robust sales tax collections are essential for aligning the state’s revenues with state economic activity. However, it is crucial not to compound the sales tax’s regressive nature by allocating the revenue generated on regressive tax programs such as property tax credits.[xliv] Past ill-planned tax cuts, like the Christie-era sales tax reduction, cost the state hundreds of millions in much-needed tax dollars while providing little in terms of economic benefits.[xlv]

Restoring the sales tax to 7 percent would generate roughly $700 million in additional revenue for the state. About one-quarter of the revenue generated — around $180 million — would come from non-residents, such as tourists and shoppers from neighboring states.[xlvi]

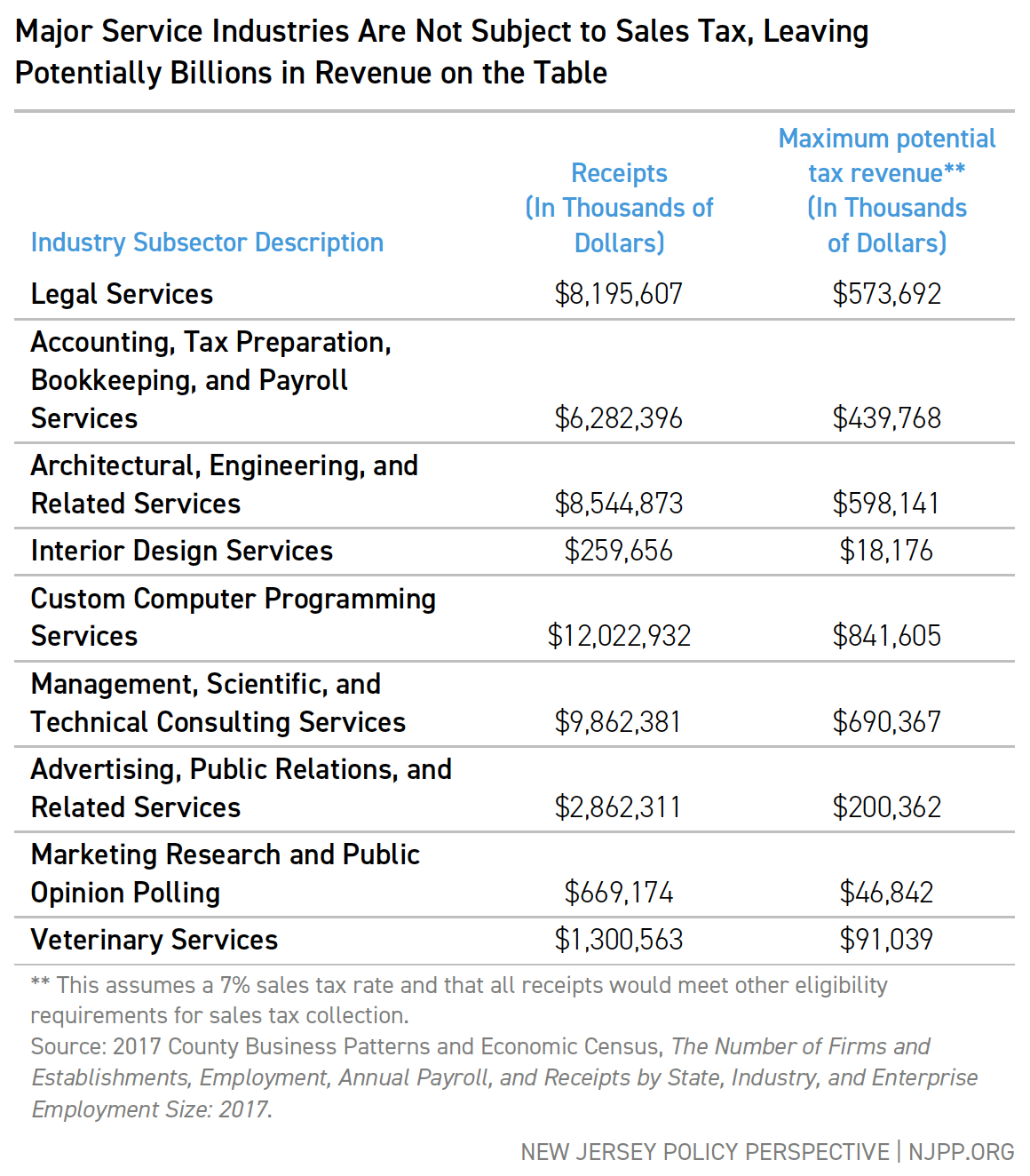

Additionally, New Jersey’s sales tax is primarily geared toward goods, even though services now make up a larger portion of the economy as a whole. Services account for nearly two-thirds of all consumer spending in the state,[xlvii] yet high-end services remained exempt. Put differently, when a family goes to buy a computer, they pay taxes on that purchase, but if a large corporation buys computing services from a third-party vendor, they do not pay taxes on that service.

Examples of services exempt from sales tax include:

- Accounting and Bookkeeping

- Architects

- Land Surveying

- Attorneys

- Engineers

- Advertising and Marketing

- Public Relations and Management Consulting

- Lobbying and Consulting

- Data Processing Services

These high-end services, categorized under “Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services” in the North American Industry Classification System, generated $67.6 billion in revenue in New Jersey, based on 2017 data,[xlviii] much of which was not subject to sales tax.[xlix]

Updating the state’s sales tax code to include these services and closing loopholes can bring in substantial revenue. Closing the car rental loophole alone could generate $174 million annually,[l] while repealing the yacht purchase tax would bring in about $15 million in additional annual revenue.[li]

The state has precedent for updating services subject to sales tax, but it has been nearly 20 years since the last major revision in 2006.[lii] That update expanded the tax to include services like pre-written computer software, flooring installation, storage units, and personal care services such as tanning salons and massage therapy.

Raise Fees on Super-Luxury Homes Sales

Proposal Overview

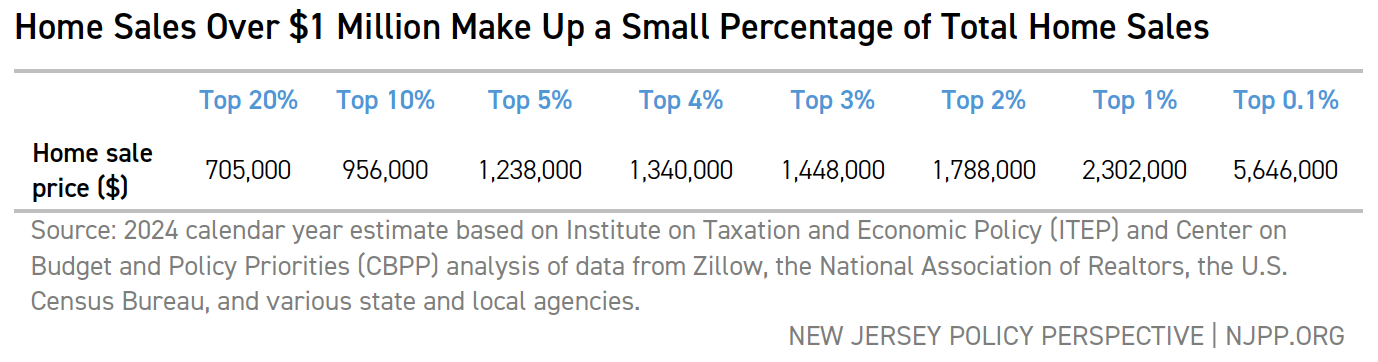

New Jersey’s market for super-luxury homes continues to grow, as homes with high price tags continue to sell faster than more moderately priced homes.[liii] Currently, New Jersey levies a 1 percent tax on home sales greater than $1 million.[liv] This proposal suggests increasing the tax to 3 percent for homes over $1 million and 5 percent for homes over $2 million. This proposal would generate about $410 million in new annual revenues while affecting only the top 10 percent of home sales.

Proposal Details

The existing fee has done little to dampen the luxury home market, with sales of very expensive homes continuing to grow while the overall housing market has cooled. While many residents struggle with the high cost of housing in New Jersey, very expensive homes continue to change hands at a high rate. However, as detailed in a recent NJPP analysis, an added fee on expensive home sales would provide substantial revenue for the state.[lv] Home sales over $1 million represent less than 10 percent of home sales in the state, with home sales over $2 million making up less than 2 percent.[lvi] These transactions affect high-income or high-wealth households, leaving the vast majority of homeowners unaffected.

Require Worldwide Combined Corporate Reporting to Fight Against Profit Offshoring

Proposal Overview

As large multinational corporations have enjoyed the lion’s share of economic growth, they have also grown sophisticated in hiding their profits, shifting to tax haven countries to avoid tax exposure in the United States. As corporations have used sophisticated tax avoidance strategies to move their profits overseas, they have hidden their true profit margins from state regulators.[lvii] Across the country, the overall corporate tax base has shrunk even as corporate profits have skyrocketed to record levels.[lviii] New Jersey can help fight back against this corporate tax offshoring through a straightforward solution: require all corporations to report profits from global subsidiaries, not just those based in the United States. This approach, called “mandatory worldwide combined reporting,” is a critical tool to address profit offshoring, which has accelerated in recent years, significantly reducing the corporate tax base.

Currently, New Jersey taxes corporations that meet a certain threshold of sales in New Jersey by applying a tax to their overall profits, based on the proportion of those sales occurring in the state.[lix] By expanding this to include all global profits, New Jersey would increase its overall tax base, raising an estimated $888 million in annual revenue simply by requiring corporations to disclose all profits, including those declared overseas.

Proposal Details

The concept of requiring full disclosure, called “mandatory worldwide combined reporting,” simplifies the complex web of corporate offshore holdings by requiring that all profits generated by companies controlled by a parent company be included in New Jersey’s corporate tax calculations.[lx] Currently, under “water’s edge reporting,” New Jersey only requires that corporations disclose profits generated by companies in the United States, taxing them based on the portion of sales made within the state.[lxi] But, by shifting profits overseas, many corporations make their biggest profits invisible to the state’s taxing authority.

Mandatory combined reporting would close this loophole and level the playing field, by forcing large multinational corporations to show where their profits are hidden. This would also benefit smaller domestic corporations that lack the resources to establish foreign subsidiaries or operate in foreign tax haven countries.

An estimate from 2019 placed the potential benefit to New Jersey of adopting worldwide combined reporting at $714 million.[lxii] This figure is now projected to be nearly $890 million adjusted for inflation.

Increase State Tax Enforcement Workforce

Proposal Overview

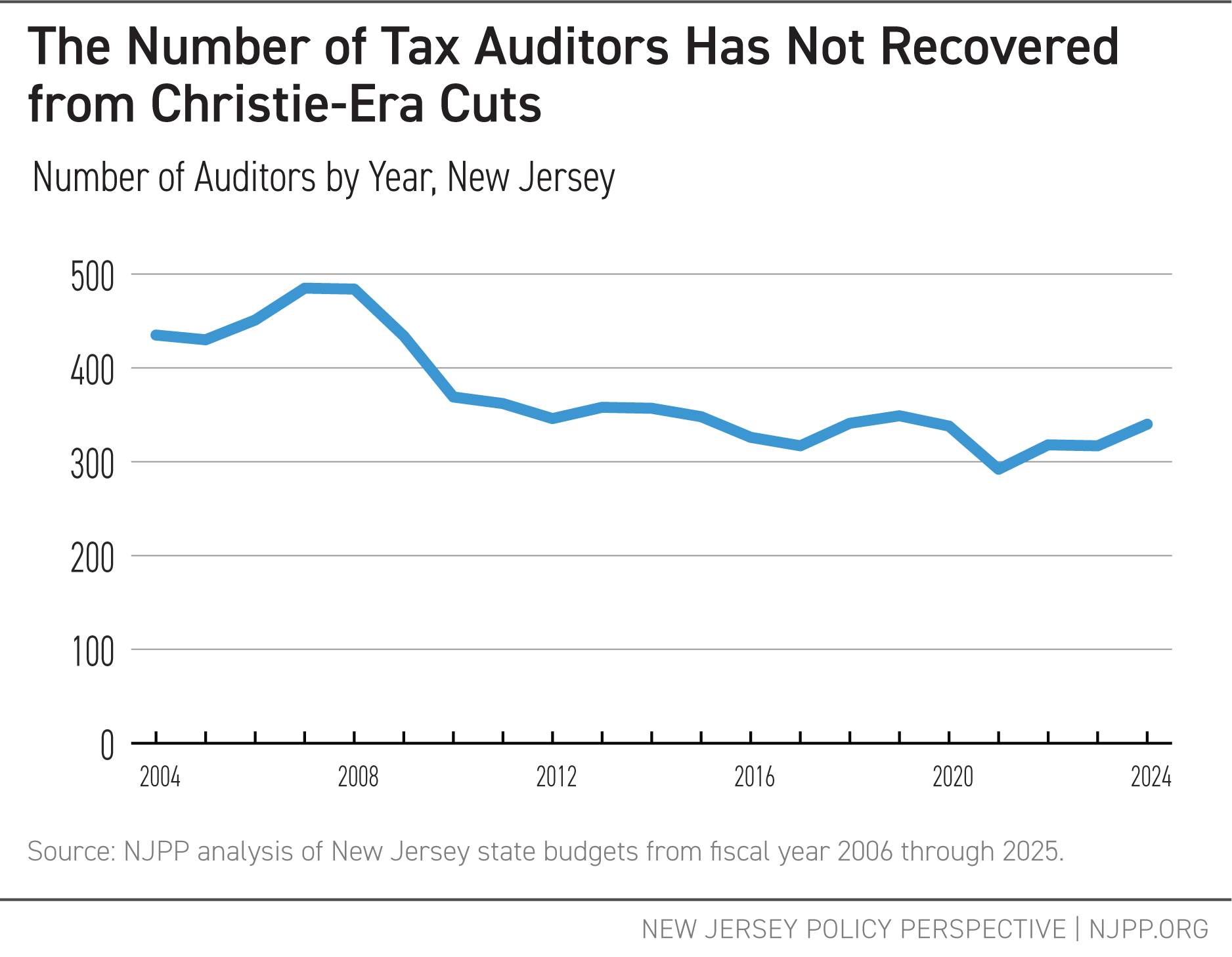

The New Jersey state’s tax division hires auditors and collectors to examine the returns of taxpayers to identify errors and collect assessments. This workforce helps ensure the state maximizes its collections and reduces fraud and errors, particularly among high-income and high-wealth taxpayers. However, the number of auditors has declined since the Great Recession. New Jersey should restore its auditor workforce to pre-Great Recession levels, increasing the number of auditors from 340 to at least 485.[lxiii] This proposal would generate about $385 million annually.

Proposal Details

Over the past 20 years, New Jersey’s auditor workforce has shrunk by 30 percent, even though the complexity of the state’s budget and tax code have grown substantially. This reduction has weakened the state’s ability to combat tax fraud and ensure accuracy, especially for complex tax returns. On average, each New Jersey auditor identifies about $2.35 million in assessments.[lxiv] Restoring the workforce to 485 would yield $341 million in additional annual revenue.[lxv] Reinstating the 20 compliance officers lost since 2004 would add another $44 million, bringing the total potential revenue increase to $385 million.[lxvi] These figures are consistent with past performance when auditor staffing levels were higher, with assessment surpassing $1 billion during from 2007 to 2010 when auditor workforces were at their peak.[lxvii]

Federal efforts to target high-income individuals and large corporations out of compliance with their tax obligations have yielded substantial collections, with nearly $1 billion in past-due taxes collected.[lxviii] Federal tax authorities have noted that the complexity of higher-income audits and auditor attrition has extended the amount of time needed to complete audits.[lxix]

What’s Next for New Jersey

New Jersey needs a set of new revenue streams that will fund the next generation of programs to improve affordability and induce economic growth for generations to come. Whether that comes in the form of increased investments in housing and infrastructure, substantial expansions of tax credits and cash assistance for working families, or increased support for K-12 and higher education, any expansions in public programs to assist affordability will need funding. However, to fully advance equity and lift up the state’s working-class and middle-class residents, these revenues must be generated progressively, ensuring that the state’s wealthiest residents pay their fair share for prosperity for all.

Broadly, this package of potential revenue raisers would set New Jersey on a path toward fiscal responsibility, generate sufficient funds to invest in growth and affordability, and reduce income and economic inequity. Without bold changes in tax policy, New Jersey runs the risk of falling back into the rut it was in at the end of the Christie administration, with a low credit rating, enormous pension and school funding liabilities, and a budget that slashed state employment and investment.[lxx] The choice is clear: New Jersey can choose prosperity for all through targeted taxation of the very wealthy, or a return to fiscal brinkmanship and the continued deferral of essential investments in the state’s well-being.

End Notes

[i] New Jersey ranks second in the nation in median income at $99,781. See Katherine Engel and Kirby G. Posey, U.S. Census Bureau, Household Income in States and Metropolitan Areas: 2023, p. 3, tbl. 1 (Sept. 2024), https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/2024/demo/acsbr-023.pdf. New Jersey ranks in the top ten in median net worth. See U.S. Census Bureau,

Wealth and Asset Ownership for Households, by Type of Asset and States: 2022, table 1,

Survey of Income and Program Participation, Survey Year 2023, https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/demo/tables/wealth/2022/wealth-asset-ownership/state_wealth_tables_dy2022.xlsx. New Jersey’s gross domestic product ranks tenth nationally. U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, SQGDP1 State quarterly gross domestic product (GDP) summary (accessed Wednesday, October 16, 2024), https://apps.bea.gov/itable/index.html?appid=70&stepnum=40&Major_Area=3&State=0&Area=XX&TableId=532&Statistic=3&Year=2024:Q2&YearBegin=-1&Year_End=-1&Unit_Of_Measure=Levels&Rank=1&Drill=1&nRange=5.

[ii] U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce. “Poverty Status in the Past 12 Months.” American Community Survey, ACS 1-Year Estimates Subject Tables, Table S1701, 2023, https://data.census.gov/table/ACSST1Y2023.S1701?q=child poverty&g=040XX00US34. Accessed on October 16, 2024.

[iii] Estelle Sommeiller & Mark Price, Economic Policy Institute, The New Gilded Age: Income Inequality in the U.S. by State, Metropolitan Area, and County at tbl. 1 (July 19, 2018), https://files.epi.org/pdf/147963.pdf.

[iv] U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Corporate Profits with Inventory Valuation Adjustment (IVA) and Capital Consumption Adjustment (CCAdj) [CPROFIT], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CPROFIT, October 16, 2024. U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Compensation of Employees: Wages and Salary Accruals [WASCUR], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/WASCUR, . https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=G8JT.

[v] New Jersey Institute for Social Justice, The Two New Jerseys by the Numbers: Racial Wealth Disparities in the Garden State (March 2023), https://njisj.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Two_New_Jerseys_By_the_Numbers_Data_Brief_3.23.23-compressed.pdf.

[vi] By contrast a regressive tax system has higher tax rates for lower-income residents. For more information on progressive and regressive tax systems, see Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States, Seventh Edition (Jan. 2024), https://sfo2.digitaloceanspaces.com/itep/ITEP-Who-Pays-7th-edition.pdf.

[vii] Alex Ambrose & Peter Chen, New Jersey Policy Perspective, Getting Back on Track: Fully Fund NJ Transit by Taxing Big Corporations, Sept. 27, 2023, https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/getting-back-on-track-fully-fund-nj-transit-by-taxing-big-corporations/.

[viii] For a review on the accumulation of insufficient funding of the school funding formula, see Bruce Baker & Mark Weber, New Jersey Policy Perspective, School Funding in New Jersey: A Fair Future for All, Part 3: The School Funding Reform Act – 2020 Update (Nov. 2020), https://www.njpp.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/NJPP-School-Funding-in-New-Jersey-A-Fair-Future-for-All-Part-3.pdf.

[ix] Gordon MacInnes & Sheila Reynertson, New Jersey Policy Perspective, The Notorious Nine: How Key Decisions Sent New Jersey’s Financial Health Spiraling Down Over Two Decades (Sept. 2016), https://www.njpp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/NJPPNotorious9Sept2016.pdf.

[x] Multi-Year Budget Workgroup, Steve Sweeney Center for Public Policy, New Jersey’s Fiscal Cliff: Current Services Budget Projections, Long-Term Economic Forecast, and the Multi-Year Structural Deficit (June 13, 2024), https://chss.rowan.edu/centers/sweeney_center/mybwreportjune2024web.pdf.

[xi] Multi-Year Budget Workgroup, Steve Sweeney Center for Public Policy, New Jersey’s Fiscal Cliff: Current Services Budget Projections, Long-Term Economic Forecast, and the Multi-Year Structural Deficit (June 13, 2024), https://chss.rowan.edu/centers/sweeney_center/mybwreportjune2024web.pdf.

[xii] Steve Wamhoff, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Extending Temporary Provisions of the 2017 Trump Tax Law: Updated National and State-by-State Estimates, Sept. 13, 2024, https://itep.org/trump-tax-law-tcja-permanent-state-by-state-estimates/.

[xiii] Nikita Biryukov, NJ Transit approves $3B budget amid outcry over fare hikes, New Jersey Monitor, Jul. 25, 2024, https://newjerseymonitor.com/2024/07/25/nj-transit-approves-3b-budget-amid-outcry-over-fare-hikes/.

[xiv] Based on analysis by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.

[xv] John Reitmeyer, Explainer: A Look Under the Hood of NJ’s Income Tax and Its Special Quirks, NJ Spotlight News, Apr. 9, 2019, https://www.njspotlightnews.org/2019/04/19-04-08-explainer-a-look-under-the-hood-of-njs-income-tax-and-its-special-quirks/.

[xvi] Data shows that the top 5 percent of households by income in New Jersey take home more than 22 percent of the state’s aggregate income. The top 20 percent take home more than 51 percent. B19082 Census 1-year 2023 estimate.

[xvii] Based on analysis by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.

[xviii] U.S. Census Bureau, State Government Tax Collections, Individual Income Taxes in New Jersey [NJINCTAX], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/NJINCTAX, October 16, 2024.

[xix] Wesley Tharpe, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Raising State Income Tax Rates at the Top a Sensible Way to Fund Key Investments (Feb. 7, 2019), https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/raising-state-income-tax-rates-at-the-top-a-sensible-way-to-fund-key.

[xx] The number of tax filers with $1 million or more in income increased from 22,720 to 33,770 between 2019 and 2021. Compare Internal Revenue Service, Statistics of Income, Table 2: Individual Income and Tax Data, by State and Size of Adjusted Gross Income, Tax Year 2019 (Dec. 2021), https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/19in31nj.xlsx with Internal Revenue Service, Statistics of Income, Table 2: Individual Income and Tax Data, by State and Size of Adjusted Gross Income, Tax Year 2021 (Feb. 2024), https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/21in31nj.xlsx.

[xxi] Samantha Waxman et al., Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Interactive Map: States Should Continue Enacting and Expanding Child Tax Credits and Earned Income Tax Credits (Aug. 24, 2024), https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/states-should-continue-enacting-and-expanding-child-tax-credits-and.

[xxii] New Jersey Division of Taxation, NJ Earned Income Tax Credit Frequently Asked Questions (last updated Dec. 2023), https://www.nj.gov/treasury/taxation/eitc/eitcfaq.shtml

[xxiii] New Jersey Division of Taxation, Child Tax Credit (last updated Jan. 5, 2024), https://www.nj.gov/treasury/taxation/individuals/childtaxcredit.shtml.

[xxiv] Elise Gould, Child Tax Credit expansions were instrumental in reducing poverty rates to historic lows in 2021, Economic Policy Institute Working Economics Blog, Sept. 22, 2022, https://www.epi.org/blog/child-tax-credit-expansions-were-instrumental-in-reducing-poverty-to-historic-lows-in-2021/.

[xxv] Vineeta Kapahi, New Jersey Policy Perspective, Building a More Immigrant Inclusive Tax Code: Expanding the EITC to ITIN Filers (July 2020),

https://www.njpp.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/NJPP-Report-Building-a-More-Immigrant-Inclusive-Tax-Code-Expanding-the-EITC-to-ITIN-Filers-1.pdf. For more on the nearly $100 billion in tax payments by undocumented immigrants including more than $1.3 billion in New Jersey alone, see Carl Davis, Marco Guzman & Emma Sifre, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Tax Payments by Undocumented Immigrants, Jul. 30, 2024, https://sfo2.digitaloceanspaces.com/itep/ITEP-Tax-Payments-by-Undocumented-Immigrants-2024.pdf.

[xxvi] N.J. Stat. Sec. 54A:4-17.1

[xxvii] Mark Lino et al., U.S. Department of Agriculture, Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion, Expenditures on Children by Families, 2015,. Miscellaneous Publication No. 1528-2015 (Mar. 2017), p. 15, https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/crc2015-march2017.pdf.

[xxviii] For additional information on proposals to expand the state’s Child Tax Credit, see Peter Chen, New Jersey Policy Perspective, How an Expanded Child Tax Credit Would Help More Hard-Working New Jersey Families, Jan. 31, 2023, https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/how-an-expanded-child-tax-credit-would-help-more-hard-working-new-jersey-families/. Analysis of an expanded child tax credit has shown that New Jersey could reduce child poverty by 25 percent with a $2,000 credit for children under age 6 and $1,700 for ages 6-18. See Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Columbia Center on Poverty and Social Policy, Child Tax Credit Options for Reducing Child Poverty (2022), https://itep.sfo2.digitaloceanspaces.com/Child-Tax-Credit-Options-New-Jersey-2022.pdf.

[xxix] New Jersey Division of Taxation, General Information: Inheritance and Estate Tax, O-10-C (Jan. 2017), https://www.nj.gov/treasury/taxation/pdf/other_forms/inheritance/o10c.pdf.

[xxx] See Samantha Waxman, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, State Taxes on Inherited Wealth, Jun. 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/issue-brief-state-taxes-on-inherited-wealth; Martin Poethke & Patrick Brennan, New Jersey Office of Legislative Services, Legislative Fiscal Estimate [Second Reprint], Assembly, No. 12, Oct. 12, 2016, https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/bill-search/2016/A12/bill-text?f=A0500&n=12_E3.

[xxxi] N.J. Stat. Sec. 54:34-2

[xxxii] Andrew Van Dam, How inheritance data secretly explains U.S. inequality, Washington Post, Nov. 10, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2023/11/10/inheritance-america-taxes-equality/.

[xxxiii] State of New Jersey Department of the Treasury, Office of Revenue and Economic Analysis, Transfer Inheritance Tax: Statistical Report for Tax Years 2015-2017 (Jul. 28, 2021), https://www.nj.gov/treasury/economics/documents/pdf/stats/Transfer-Inheritance-Tax-Statistical-Report-TY-2015-2017.pdf at 5.

[xxxiv] Andrew Van Dam, How inheritance data secretly explains U.S. inequality, Washington Post, Nov. 10, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2023/11/10/inheritance-america-taxes-equality/.

[xxxv] Bhutta, Neil, Andrew C. Chang, Lisa J. Dettling, and Joanne W. Hsu (2020). “Disparities in Wealth by Race and Ethnicity in the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances,” FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, September 28, 2020, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.2797.

[xxxvi] N.J. Stat. Sec. 54:38-1.a.(4). Previously the minimum size of an estate to be eligible for the tax was $675,000. As with other estate taxes including the federal estate tax, wealthy residents could still avoid the tax through a variety of methods. See U.S. Senate Committee on Finance, Estate Tax Schemes: How America’s Most Fortunate Hide Their Wealth, Flout Tax Laws, and Grow the Wealth Gap, Oct. 12, 2017, https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/101217%20Estate%20Tax%20Whitepaper%20FINAL1.pdf.

[xxxvii] Martin Poethke & Patrick Brennan, New Jersey Office of Legislative Services, Legislative Fiscal Estimate [Second Reprint], Assembly, No. 12, Oct. 12, 2016, https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/bill-search/2016/A12/bill-text?f=A0500&n=12_E3.

[xxxviii] Personal property made up 70 percent of estates, compared to real property at 18 percent in tax year 2017, the most recent year of available data State of New Jersey Department of the Treasury, Office of Revenue and Economic Analysis, Transfer Inheritance Tax: Statistical Report for Tax Years 2015-2017 (Jul. 28, 2021), https://www.nj.gov/treasury/economics/documents/pdf/stats/Transfer-Inheritance-Tax-Statistical-Report-TY-2015-2017.pdf at 6.

[xxxix]Samantha Waxman, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, State Taxes on Inherited Wealth, Jun. 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/issue-brief-state-taxes-on-inherited-wealth, n.1.

[xl] Given that inheritance tax data is limited, this estimate is based on key assumptions. First, the estimate assumes that the effective tax rate on Class A (lineal descendants and spouses) and Class C (siblings) beneficiaries would be the same as the current effective tax rate on Class D beneficiaries if the current Class D marginal rate structure were applied to Class A and Class C beneficiaries. Second, it assumes that the exempt estate is evenly distributed over the currently exempt beneficiaries, even though lineal descendants and spouses likely inherit larger inheritances than unrelated persons and more distant relations. Third, the estimate assumes that the ratio of share of returns between Class C and Class D beneficiaries correlates with the size of the tax base for each category.

[xli] Sheila Reynertson, New Jersey Policy Perspective, Modernizing New Jersey’s Sales Tax Will Level

the Playing Field & Help the Economy Thrive, Feb. 2018,

https://www.njpp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/NJPPSalesTaxReformsFeb2018.pdf.

[xlii] For a comprehensive look at New Jersey’s sales and use tax exemptions, see New Jersey Division of Taxation, New Jersey Sales Tax Guide, Tax Topic Bulletin S&U-4, July 2022, https://www.nj.gov/treasury/taxation/pdf/pubs/sales/su4.pdf.

[xliii] To see how New Jersey’s sales tax regressivity is counteracted by its progressive income tax, see Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Who Pays? New Jersey State and Local Tax Shares of Family Income (Jan. 2024), https://sfo2.digitaloceanspaces.com/itep/itep-whopays7-New-Jersey.pdf.

[xliv] Testimony of Peter Chen, Senior Policy Analyst, New Jersey Policy Perspective, Before Stay NJ Task Force, March 13, 2024, https://www.njpp.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/NJPP-StayNJ-Committee-Testimony-03-13-24.pdf.

[xlv] Based on analysis of data from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.

[xlvi] Based on analysis of data from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.

[xlvii] U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, “SAPCE1 Personal consumption expenditures (PCE) by major type of product 1” (accessed Wednesday, October 16, 2024), https://apps.bea.gov/itable/?ReqID=70&step=1&_gl=1*1c592j9*_ga*NDUzNjQ0MzAyLjE3MjY1MTAxMDc.*_ga_J4698JNNFT*MTcyNjUxMDEwNy4xLjAuMTcyNjUxMDEwNy42MC4wLjA.#eyJhcHBpZCI6NzAsInN0ZXBzIjpbMSwyOSwyNSwzMSwyNiwyNywzMF0sImRhdGEiOltbIlRhYmxlSWQiLCI1MjQiXSxbIk1ham9yX0FyZWEiLCIwIl0sWyJTdGF0ZSIsWyIwIl1dLFsiQXJlYSIsWyIzNDAwMCJdXSxbIlN0YXRpc3RpYyIsWyIyIiwiMTMiXV0sWyJVbml0X29mX21lYXN1cmUiLCJMZXZlbHMiXSxbIlllYXIiLFsiLTEiXV0sWyJZZWFyQmVnaW4iLCItMSJdLFsiWWVhcl9FbmQiLCItMSJdXX0=.

[xlviii] U.S. Census Bureau, Survey of U.S. Businesses, The Number of Firms and Establishments, Employment, Annual Payroll, and Receipts by State, Industry, and Enterprise Employment Size: 2017 (2021), available at https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/econ/susb/2017-susb-annual.html.

[xlix] New Jersey Division of Taxation, New Jersey Sales Tax Guide, Tax Topic Bulletin S&U-4, July 2022, https://www.nj.gov/treasury/taxation/pdf/pubs/sales/su4.pdf, pp. 14-15.

[l] NetChoice, Big Rental’s Rules of the Road: Tax Loopholes and Sneaky Subsidies, Policy Note, April 2020, https://netchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Turo-VLF-v.3.pdf, p. 9. The $174 million estimate adjusts the annual estimate of $142 million in 2020 for 2024 dollars.

[li] Sheila Reynertson, New Jersey Policy Perspective, Modernizing New Jersey’s Sales Tax Will Level

the Playing Field & Help the Economy Thrive, Feb. 2018, https://www.njpp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/NJPPSalesTaxReformsFeb2018.pdf.

[lii] Pub. L. 2006, c.44.

[liii] Allison Pries, The housing market in N.J. has slowed — except for these types of homes, NJ Advance Media for NJ.com, Mar. 10, 2024, https://www.nj.com/realestate-news/2024/03/the-housing-market-in-nj-has-slowed-except-for-these-types-of-homes.html.

[liv] NJ Stat. Sec, 46:15-7.2 (2023)

[lv] Peter Chen, New Jersey Policy Perspective, Taxing “Super Luxury” Home Sales Could Make New Jersey Affordable for More Residents, Sep. 10, 2024, https://www.njpp.org/publications/blog-category/taxing-super-luxury-home-sales-could-make-new-jersey-affordable-for-more-residents/.

[lvi] Peter Chen, New Jersey Policy Perspective, Taxing “Super Luxury” Home Sales Could Make New Jersey Affordable for More Residents, Sep. 10, 2024, https://www.njpp.org/publications/blog-category/taxing-super-luxury-home-sales-could-make-new-jersey-affordable-for-more-residents/.

[lvii] Michael Mazerov, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, States Can Fight Corporate Tax Avoidance by Requiring Worldwide Combined Reporting, June 27, 2024, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/states-can-fight-corporate-tax-avoidance-by-requiring-worldwide-0.

[lviii] Josh Bivens, Economic Policy Institute, Reclaiming Corporate Tax Revenues, April. 14, 2022, https://www.epi.org/publication/reclaiming-corporate-tax-revenues/ at figure G.

[lix] Michael Mazerov, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, The “Single Sales Factor” Formula for State Corporate Taxes, Sept. 1, 2005, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/archive/3-27-01sfp.htm.

[lx] Michael Mazerov, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, States Can Fight Corporate Tax Avoidance by Requiring Worldwide Combined Reporting, June 27, 2024, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/states-can-fight-corporate-tax-avoidance-by-requiring-worldwide-0.

[lxi] N.J. Admin. Code § 18:7-21.15 (2024).

[lxii] Richard Phillips, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, A Simple Fix for a $17 Billion Loophole: How States Can Reclaim Revenue Lost to Tax Havens, Jan. 17, 2019, https://itep.org/a-simple-fix-for-a-17-billion-loophole/.

[lxiii] The state peaked at 485 auditors in fiscal year 2007.

[lxiv] In Fiscal Year 2007, New Jersey peaked at 485 auditors. See State of New Jersey Budget, Fiscal Year 2008-2009 at D-425. The per auditor assessment is based on the Revised FY 2024 figure in State of New Jersey Budget, Fiscal Year 2025, at D-402.

[lxv] In Fiscal Year 2007, New Jersey peaked at 485 auditors. See State of New Jersey Budget, Fiscal Year 2008-2009 at D-425. The per auditor assessment is based on the Revised FY 2024 figure in State of New Jersey Budget, Fiscal Year 2025, at D-402.

[lxvi] In Fiscal Year 2007, New Jersey peaked at 290 auditors. See State of New Jersey Budget, Fiscal Year 2008-2009 at D-425. The per collector collection is based on the Revised FY 2024 figure in State of New Jersey Budget, Fiscal Year 2025, at D-402.

[lxvii] NJPP analysis and inflation adjustment of state budget data from fiscal years 2004 through 2024. In fiscal year 2009, assessments reached over $1.5 billion in 2024 dollars.

[lxviii] Press Release, Internal Revenue Service, IRS tops $1 billion in past-due taxes collected from millionaires; compliance efforts continue involving high-wealth groups, corporations, partnerships, July 11, 2024, https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/irs-tops-1-billion-in-past-due-taxes-collected-from-millionaires-compliance-efforts-continue-involving-high-wealth-groups-corporations-partnerships.

[lxix] Government Accountability Office, Report to the Chairman, Subcommittee on Oversight, Committee on Ways and Means, House of Representatives, Tax Compliance: Trends of IRS Audit Rates and Results for Individual Taxpayers by Income (May 2022), https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-22-104960.pdf, pp. 10-16.

[lxx] John Reitmeyer, The List: Tracking NJ’s 10 Credit-Rating Downgrades Under Gov. Christie, NJ Spotlight News, Nov. 21, 2016, https://www.njspotlightnews.org/2016/11/16-11-20-the-list-tracking-nj-s-10-credit-rating-downgrades-under-gov-christie/.