A teacher shortage is hitting the nation, and New Jersey is no exception.[1] The problem has become so widespread that the Legislature’s Joint Committee on Public Schools recently held hearings on the issue, at which school leaders described shrinking hiring pools, fewer certificated teachers being available as long-term substitutes, and a surge of retirements. [2]

Schools can adequately replace these teachers if enough well-educated workers consider a career in public education. Unfortunately, even before the increased pressures on teachers and more school staff considered leaving their positions, fewer candidates were enrolling in and completing teacher training programs. If New Jersey does not act soon, there will not be enough qualified candidates to replace teachers leaving the profession.

The Decline in New Jersey Teacher Candidates Continues

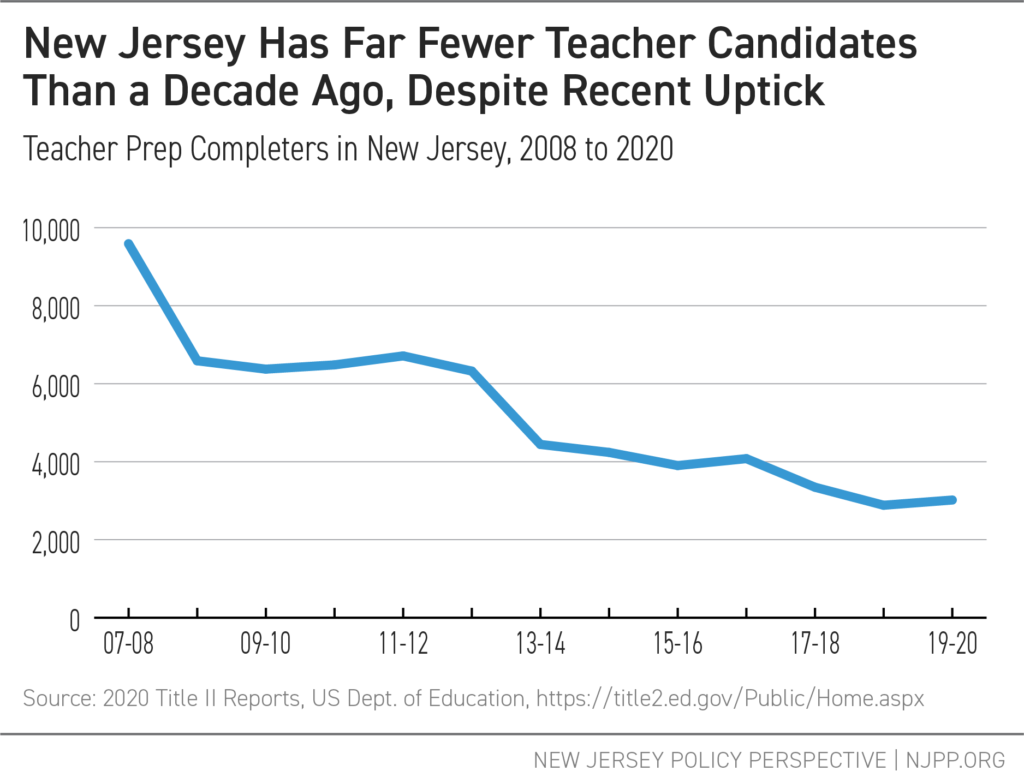

The number of those completing teacher preparation has declined sharply in New Jersey. The 2018-19 school year was the first time in two decades when the number of New Jersey’s new teacher candidates was below 3,000, according to the most recently available data.[3]

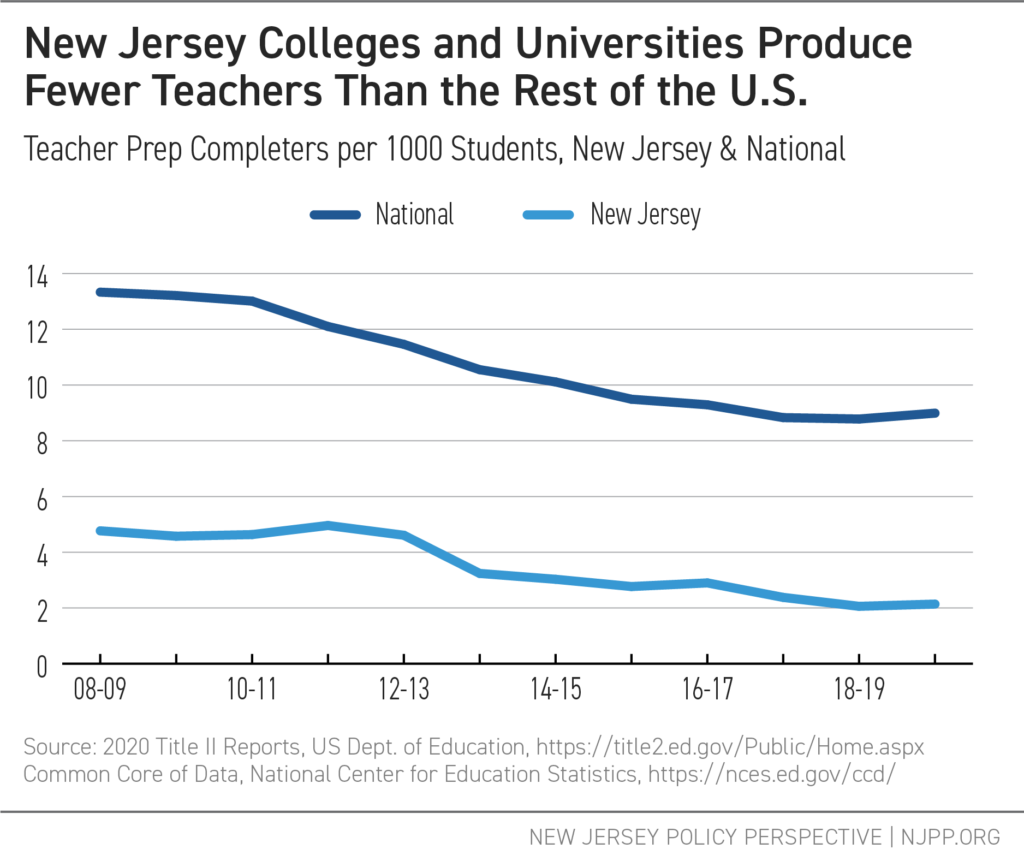

Decreases in the number of students do not explain the teacher decline. Seven years ago, almost five people completed teacher preparation for every 1,000 students in New Jersey; now, there are barely two.

On top of that, New Jersey’s colleges and universities – the providers of teacher training– produce far fewer teachers per 1,000 students than the rest of the nation, suggesting that the Garden State might be over reliant on out-of-state teacher trainings programs.

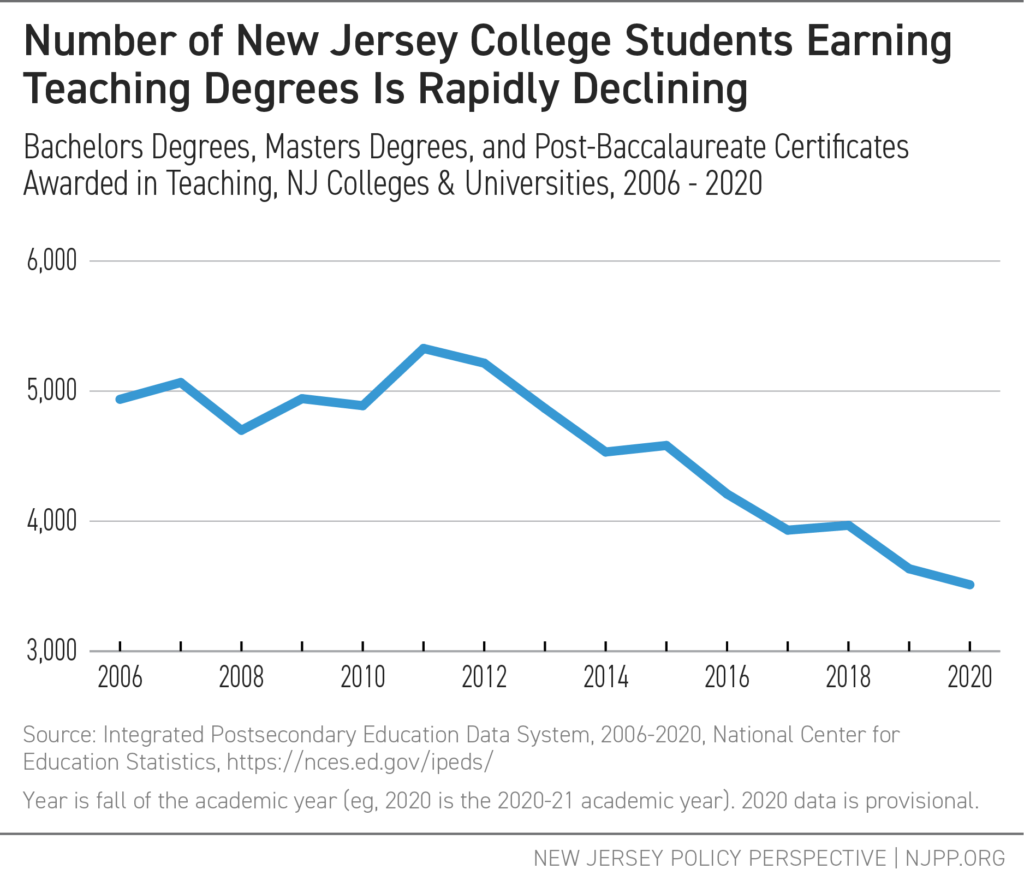

Not all teacher training programs lead to college degrees that prepare candidates for a career in teaching. But the number of teaching degrees awarded in a year is still an important measure of educator recruitment. The most recent data is troubling: New Jersey’s colleges and universities awarded a record low number of teaching degrees in 2020.[4]

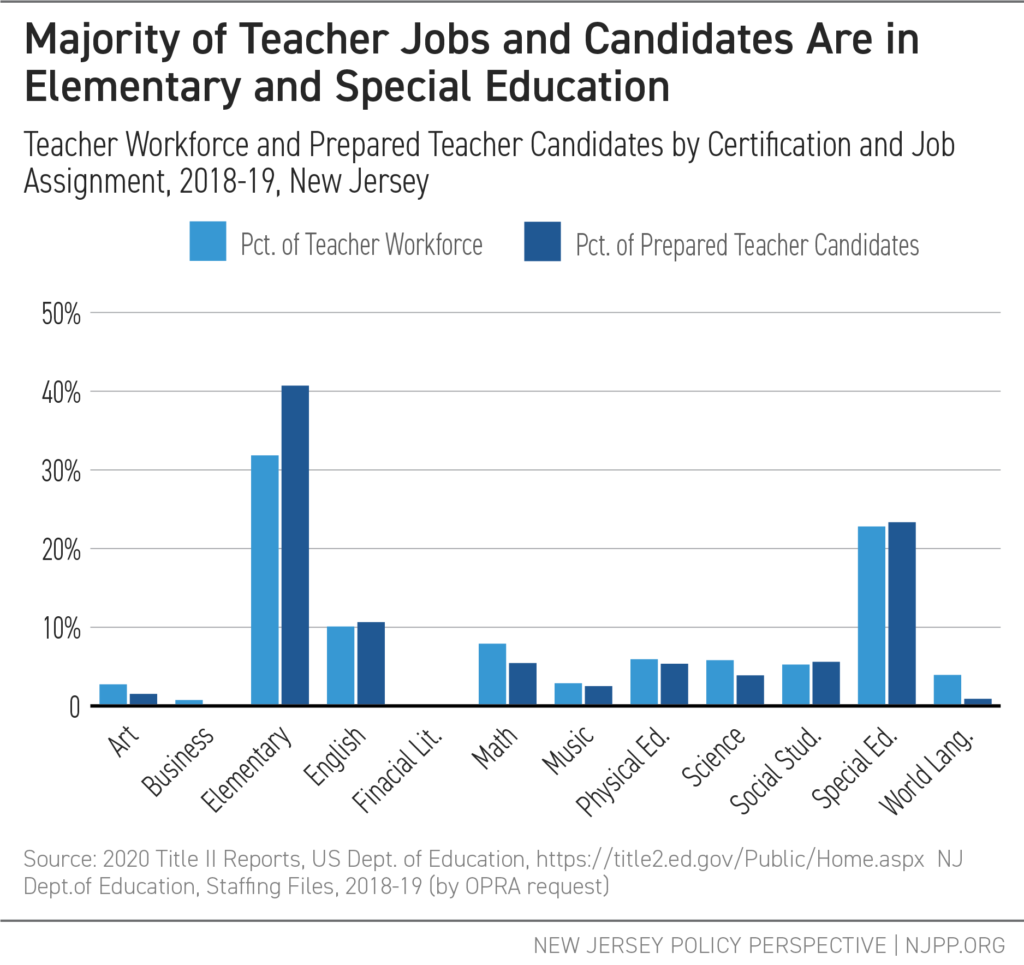

Some reports have noted that teacher shortages are particularly acute in math, science, and special education.[5] To explore this issue, the graph below shows the proportion of the number of people completing teacher training programs and earning credentials in a variety of areas. The graph also shows these proportions for the New Jersey teacher workforce in the same year.[6] As an example: 41 percent of the teacher candidates who completed their programs in 2018-19 earned a credential in elementary education. In contrast, 32 percent of the teacher workforce held a position teaching in elementary education that same year.

For the reasons below, the solution to the problem of teacher shortages is not simply to shift teacher candidates away from areas such as elementary education and toward math and other understaffed areas.

- While math and science teacher candidates are proportionally “underproduced” compared to elementary candidates, the same is true for foreign language and art teachers, as well as, to a lesser degree, music, and physical education teachers. So the problem of “underproducing” teachers is not confined to only a few curricular areas.

- Though special education is reportedly a hard-to-staff area, teacher candidates are proportionally overproduced, albeit by a slim margin. Shifting more teachers away from elementary and toward special education might help, but only if there are enough overall certifications to meet school districts’ staffing needs in all areas of teaching.

- Even if elementary teachers are “overproduced,” excess teachers are needed for positions as long-term and short-term substitutes. As numerous school leaders testified before the Joint Committee on the Public Schools, the lack of qualified personnel to fill teaching positions during maternity leaves and sick leaves, or due to mid-year retirements, has become a serious problem.[7] Having more certificated candidates than full-time positions creates a pool of qualified workers who are available to fill these jobs.

Recommendations

While getting teacher candidates to consider teaching in hard-to-staff areas is important, there is little evidence that this alone will solve the current teaching shortage, especially if those completing teacher preparation programs find the profession unsatisfying and opt to leave after a short time for other careers. To deal with teacher shortages, getting more overall qualified candidates to enter and remain in the teaching profession must be the primary goal. These recommendations should be considered to improve the recruitment and retention of teachers:

- Increase teacher compensation to attract the best candidates. Recent research confirms a well-documented “teacher wage gap,” even when benefits are considered in addition to salary.[8] In today’s tight labor market, school districts are at a disadvantage compared to fields that can offer better wages, flexible schedules, and less pressure in the workplace.

- Shore up the state teacher pension system and stop degrading teacher health care benefits. As NJPP reported previously, teacher retirement and health care benefits have eroded over the past decade[9] And this affects newer teachers more than veterans. New pension “tiers,” for example, have led to benefits packages that are substantially less generous for teachers in their 20s and 30s compared to those earned by older teachers.[10] If degraded benefits are not replaced with better wages, young, well-qualified job aspirants will have even less incentive to become teachers.

- Streamline the process of obtaining a teacher certification as much as possible without sacrificing rigor. The state continues to implement programs like EdTPA, a portfolio assessment for student teachers, that recent research shows to be both ineffective and potentially harmful. These barriers to entry should be removed immediately.[11]

- All of the state’s teacher preparation providers should continue to work together to attract teacher candidates of color. Research shows there are many benefits to a diverse teacher workforce.[12] New Jersey should expand its programs to recruit and retain teachers of color.

- New Jersey’s leaders should commit to improving the state’s level of appreciation and regard for its educators. Teachers have been caught in the middle of culture war battles over masking, critical race theory, gender identity, sexual orientation, and other issues. New Jersey, unlike other states, has wisely avoided introducing controversial laws that would surveil and punish teachers (and students) for simply doing their jobs. Policymakers must continue, through their words and actions, to send a clear message to prospective teachers that New Jersey values its educators, sees them as professionals, and supports their work.

End Notes

[1] Cooper, D. and Hickey, S.M. (February 3, 2022) Raising pay in public K–12 schools is critical to solving staffing shortages. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/solving-k-12-staffing-shortages/

[2] Joint Committee on the Public Schools, NJ Legislature. Tuesday, February 22, 2022 https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/live-proceedings/2022-02-22-10:00:00/JPS/Meeting

[3] Figures for 2016-17 and 2017-18 do not match our 2019 report as those figures were updated in later data releases.

[4] To determine the number of degrees awarded that are directly relevant to teaching, I sum the number of bachelor’s and master’s degrees awarded in education and add certificates above the baccalaureate level. I only include institutions that are designated in the IPEDS data as offering teacher certification. I then subtract all degrees with Classification of Instructional Programs (CIP) codes designated as the following: Curriculum and instruction; Educational Administration and Supervision; Educational/Instructional Media Design; Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research; Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education; Education, Other. This method likely overstates the number of degrees awarded that would be directly relevant to teaching, as degrees that do not lead to certification may still be included in the total.

[5] Teacher Shortage Areas. U.S. Department of Education. https://tsa.ed.gov/#/home/

[6] The Title II data includes subject area codes that align with staffing data from the NJDOE; however, there are differences. For this graph, I exclude all observations in the staffing data that designate staff as administrators, teacher coaches, educational service providers (counselors, nurses, etc.), or non-certificated staff. I also exclude teachers of family and consumer sciences, industrial arts, and vocational education; these areas are not included in the Title II data. Special education positions are designated in the staffing data by their “jobcode subcategory”; I align these positions with the Title II codes for teachers of students with disabilities, teachers of deaf or hard of hearing students, or teachers of blind or visually impaired students. All of these categories are designated “special education” in the graph. Teachers of middle grades (5-8) are assigned to curricular areas; for example, a teacher with a “Mathematics Grades 5-8” jobcode is designated as teaching math. Elementary teachers, including those with jobcodes in elementary math, English, science, and social studies are assigned to the “elementary” category. For teachers with multiple job codes I use the first code designated (“job code 1”).

[7] Jennings, Rob (2/22/22). “Teacher shortage is a ‘crisis,’ N.J. state legislators say after educators raise alarm.” NJ.com. https://www.nj.com/education/2022/02/teacher-shortage-is-a-crisis-nj-state-legislators-say-after-educators-raise-alarm.html

[8] Cooper, D. and Hickey, S.M. (February 3, 2022) Raising pay in public K–12 schools is critical to solving staffing shortages. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/solving-k-12-staffing-shortages/

Weber, M. (2019) New Jersey’s Teacher Workforce, 2019: Diversity Lags, Wage Gap Persists, pp. 26-28. https://www.njpp.org/reports/in-brief-new-jerseys-teacher-workforce-2019-diversity-lags-and-wage-gap-persists.

[9] Weber, M. (2019) New Jersey’s Teacher Workforce, 2019: Diversity Lags, Wage Gap Persists, pp. 26-28. https://www.njpp.org/reports/in-brief-new-jerseys-teacher-workforce-2019-diversity-lags-and-wage-gap-persists.

[10] “Retirement Planning Member Guidebook” (January, 2022). New Jersey Department of Pensions and Benefits. https://www.nj.gov/treasury/pensions/documents/forms/sp0774.pdf

[11] Gitomer, D. H., Martínez, J. F., Battey, D., & Hyland, N. E. (2019). Assessing the Assessment: Evidence of Reliability and Validity in the edTPA. American Educational Research Journal. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831219890608

Chung, Bobby W., and Jian Zou. (2021). Teacher Licensing, Teacher Supply, and Student Achievement: Nationwide Implementation of edTPA. (EdWorkingPaper: 21-440). Retrieved from Annenberg Institute at Brown University: https://doi.org/10.26300/ppz4-gv19

[12] Weber, M. (2019) New Jersey’s Teacher Workforce, 2019: Diversity Lags, Wage Gap Persists, pp. 26-28. https://www.njpp.org/reports/in-brief-new-jerseys-teacher-workforce-2019-diversity-lags-and-wage-gap-persists.