Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused tremendous challenges for New Jersey’s workers, from unsafe working conditions to unprecedented job loss. While some portions of New Jersey’s economy are recovering, the job market is far from pre-pandemic levels and employment gains have not been equally distributed. In addition, many essential workers continue to perform work requiring face-to-face interactions, risking exposure to the virus as they carry out critical functions like growing and preparing food, caring for our loved ones, and providing transportation.

New laws expanding workplace protections and safety net programs have played an important role in supporting workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. While the crisis has not ended, several of these programs and policies have been terminated or allowed to expire, including expansions to unemployment insurance. Moreover, existing benefits and protections are not available to all workers, as many New Jersey residents continue to be systematically excluded from pandemic relief programs altogether.

This report includes an analysis of employment trends during the past year and offers recommendations to support a stronger and more equitable recovery for all workers.

Pandemic Safety Net Provides Crucial Support, but Falls Short of Need

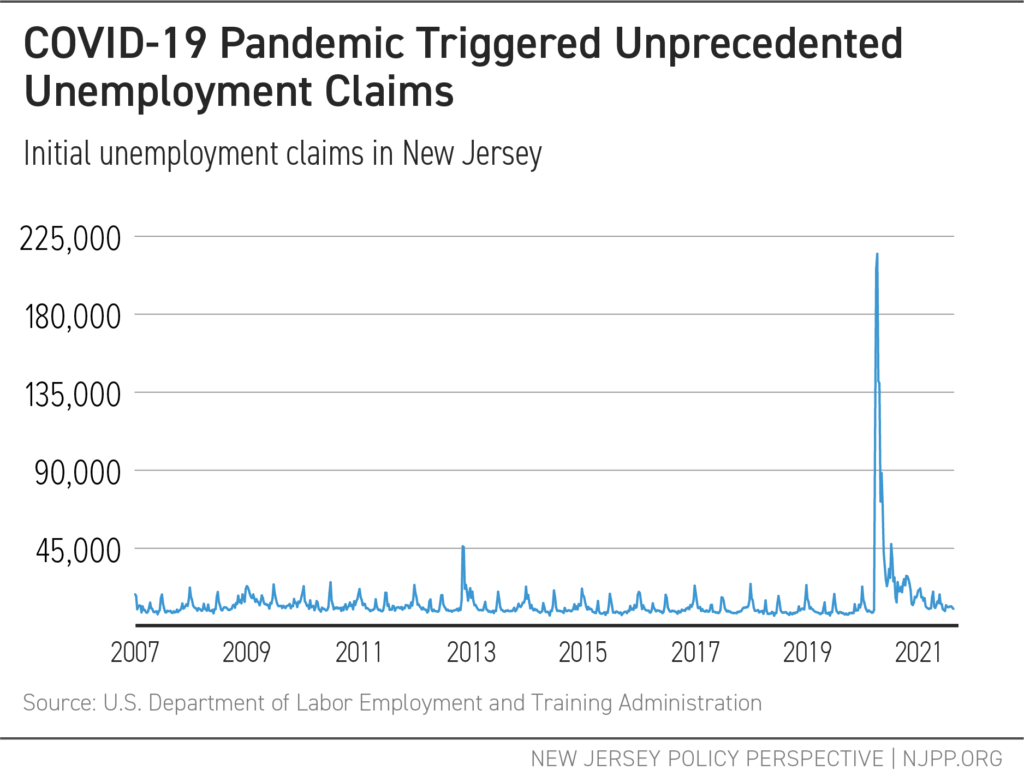

Unemployment insurance has been a critical lifeline for many workers harmed by the pandemic by providing income support to those who lost their jobs.[i] Since the onset of the pandemic, over two million initial unemployment insurance claims have been filed in New Jersey.[ii] Unemployment insurance benefits not only support workers’ wellbeing and economic security but also the broader economy by sustaining consumer demand for goods and services.

The state has been able to support many workers who lost their jobs in part through aid from the federal government. Specifically, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and American Rescue Plan (ARP) Act provided necessary funding to not only respond to the crisis, but also to rebuild a stronger economy.

However, many of these vital programs expire by September 6, Labor Day. For workers in New Jersey, the last payable week of benefits for pandemic unemployment programs was the week ending on September 4th:

- Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC) provided additional weeks of federally funded unemployment benefits to workers who exhausted regular unemployment insurance.

- Pandemic Unemployment Assistance Program (PUA) provided support to workers who are not typically eligible for state unemployment insurance, including self-employed workers, people seeking part-time work, and those who had to leave work for certain family reasons.

- Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC) provided a weekly supplement to workers receiving unemployment insurance benefits.

There will be some reprieve for certain workers as these programs expire. For instance, some workers facing long-term unemployment and currently on PEUC may be able to continue to receive unemployment insurance by shifting to the Extended Benefits (EB) program, which provides additional weeks of compensation to workers who have exhausted their regular unemployment benefits in states facing increased rates of unemployment.[iii]

Among the 133,000 workers on PEUC in New Jersey, an estimated 106,000 will be able to receive EB, according to The Century Foundation.[iv]

Another 259,000 workers who were receiving PUA will no longer get the support they need.[v] As PUA recipients are ineligible for traditional unemployment, they will lose their benefits without other options for unemployment insurance. In total, an estimated 287,000 New Jersey workers on PUA and PEUC lost all unemployment benefits on September 4, 2021. Workers who are eligible for traditional unemployment insurance will continue to receive unemployment benefits, however, they will no longer receive the $300 supplement.

Excluded Workers Pushed Further Behind

Federal pandemic unemployment insurance programs provided financial support to many, but not all, workers who lost their jobs, as many New Jersey residents were left out, including certain immigrants, people recently released from the carceral system, and workers in the informal economy, including day laborers and domestic workers.

To lift these discriminatory barriers to critical financial support, the federal unemployment insurance program and immigration policy must be reformed. To that end, federal lawmakers are considering creating permanent protections and a path to citizenship for DACA recipients, TPS holders, farmworkers, and other essential workers, which would not only improve the economic security of these workers, but also improve their ability to contribute to and strengthen New Jersey’s vibrant communities and local economies. In the meantime, state lawmakers can temporarily address shortfalls in federal unemployment insurance and other safety net programs by making targeted investments in communities that are often excluded from public programs.

In May 2021, Governor Murphy announced a $40 million fund to provide direct payments to workers excluded from federal pandemic relief.[vi] The proposed structure for this program, a one time payment of up to $2,000 per household, will provide much-needed support, but falls far short of the needs of workers who faced financial hardship as a result of the pandemic. In a state with half a million undocumented immigrants, the proposed fund level will only reach a small portion of New Jersey’s workers excluded from most other forms of relief.[vii] Meanwhile, several states and localities, including neighboring New York, are providing relief that is much closer to unemployment insurance.

New Jersey’s Labor Market Gains Are Unevenly Distributed

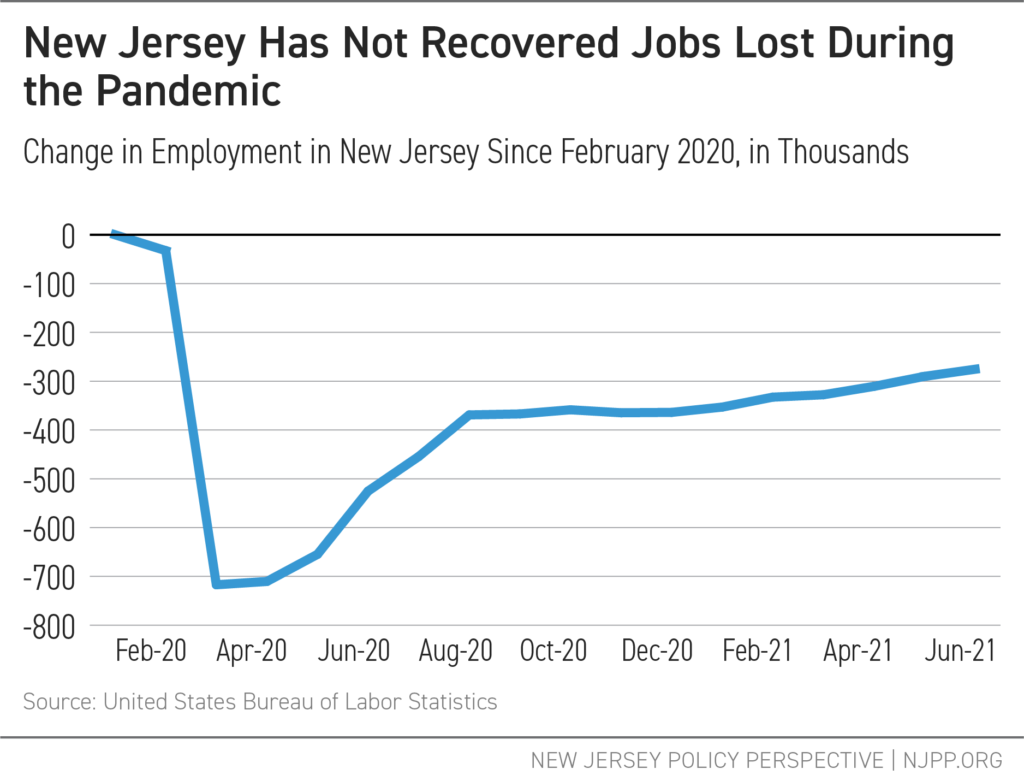

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, New Jersey’s labor market lost an unprecedented 717,000 jobs as employment plummeted from 4.2 million in February 2020 to 3.5 million in April 2020.[viii] New Jersey has seen steady job growth in recent months, recovering 62 percent of jobs lost in March and April 2020. More than one year later, a substantial gap in the labor market remains — in July 2021, New Jersey had nearly 276,000 fewer jobs than just before the pandemic, according to the latest jobs report.[ix]

While the full impact of the recent surge in COVID-19 cases remains unknown, this resurgence will heighten concerns about health and safety among both workers and consumers and could lead to the loss of recent gains in employment.

Given the nature of the current crisis, service-providing industries involving high levels of interaction among people face disproportionate job loss. Following national trends, New Jersey’s leisure and hospitality jobs were especially hard-hit. Leisure and hospitality jobs in New Jersey dropped from 400,000 jobs in February 2020 to 198,000 jobs in April 2020 — half of total pre-pandemic employment.[x] While this industry has seen substantial job growth in recent months, employment in leisure and hospitality remains more than 20 percent below pre-pandemic levels.[xi] The workforce in this industry includes a disproportionately large share of women, people of color, young adults, and low-paid workers.[xii] Even within this sector, workers earning the lowest wages as well as women and people of color experienced the greatest losses.[xiii]

Inequities in Unemployment and Underemployment Persist

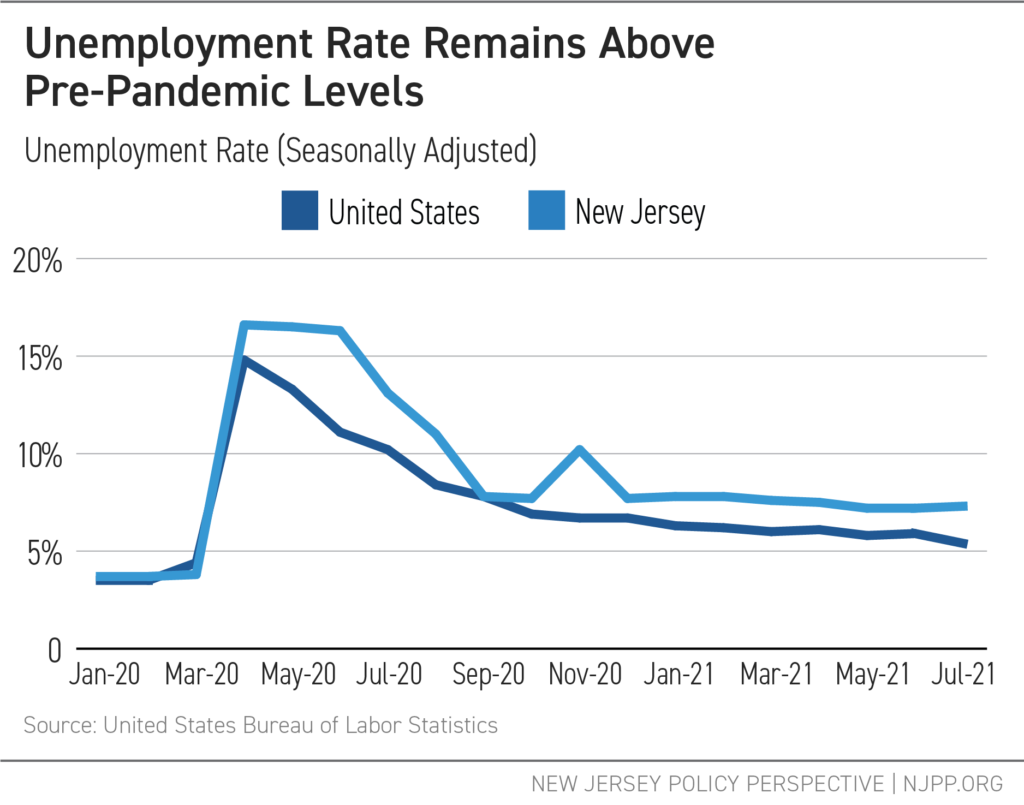

New Jersey’s unemployment rate skyrocketed from 3.8 percent in March 2020 to 16.6 percent in April 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Since then, the unemployment rate has partially recovered to 7.3 percent statewide.[xiv] The unemployment rate measures the share of the labor force that is actively seeking employment within the past four weeks but unable to secure work.

While the number of unemployed people increased among all groups of workers during the pandemic, job loss was not felt evenly due to persistent disparities in access to education, housing, wealth, and employment. Accordingly, employment is not recovering equally:

- Employment in low-wage jobs remains 28 percent lower than pre-pandemic levels.

- Employment in middle-wage jobs has grown 3 percent higher than pre-pandemic levels.

- Employment in high wage jobs has recovered from the initial impact of the pandemic and is now 5 percent higher than pre-pandemic levels.[xv]

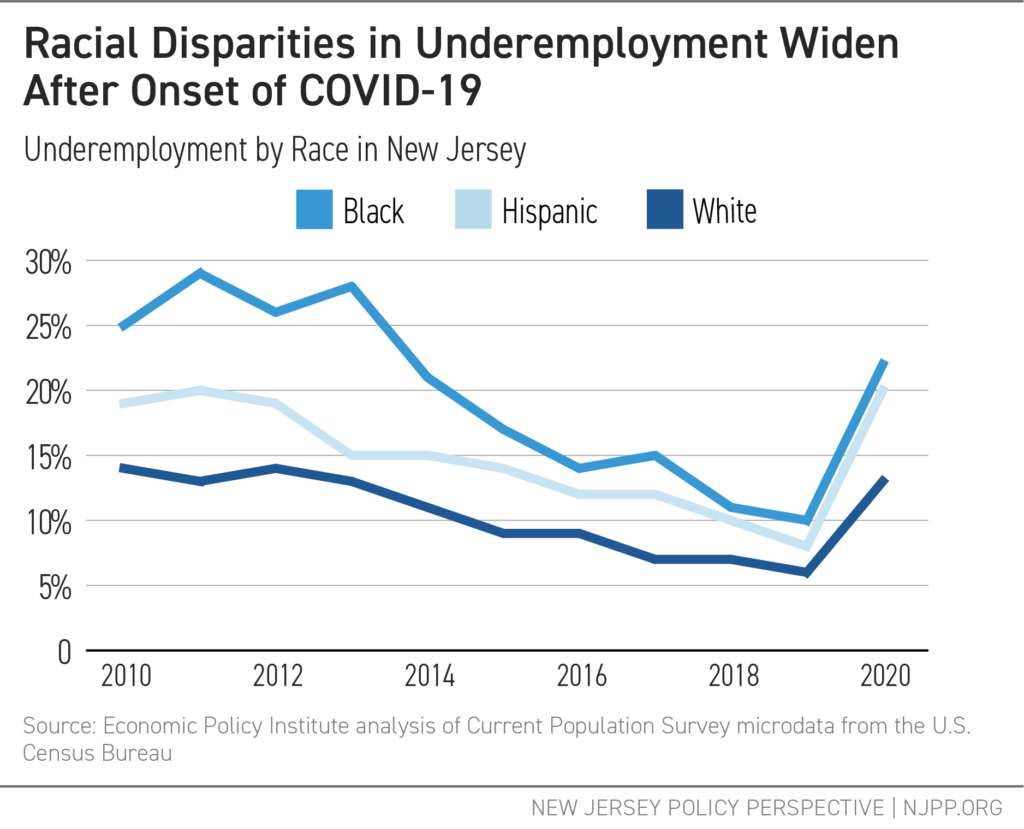

For Black and Hispanic/Latinx New Jerseyans workers, recovery has been even more challenging. Specifically, in 2020, Black workers were 77 percent more likely to be unemployed and Hispanic/Latinx workers were 60 percent more likely to be unemployed than white workers.[xvi]

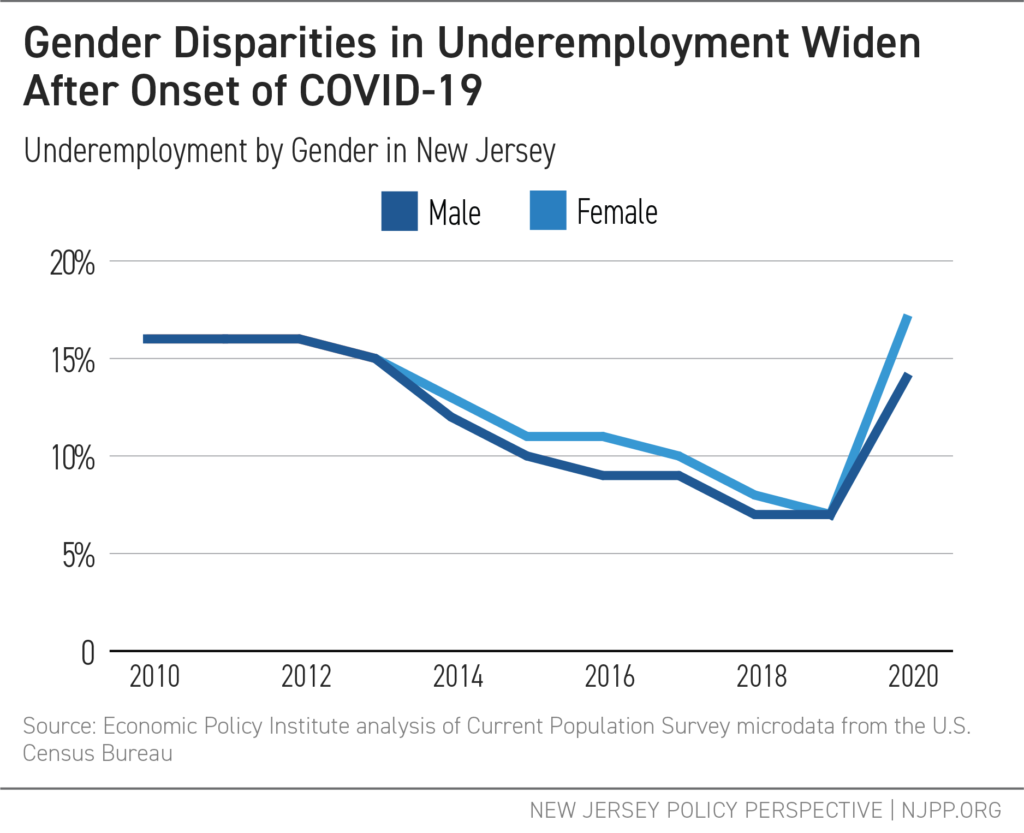

Demographic patterns in underemployment since the onset of the pandemic reveal a similar pattern. Racial inequities in underemployment in New Jersey not only persisted after the onset of COVID-19, but widened, as underemployment rates rose more sharply for Black and Latinx workers than for white workers. In 2020, unemployment rates among Black and Hispanic workers in New Jersey were each over 20 percent, while only 12.5 percent of white workers were underemployed.[xvii] Underemployment is a measure of the share of the labor force that is either unemployed or working part time but wants to work full time, or wants to work and is available to work but has given up actively seeking work in the last four weeks.

Gender disparities in underemployment also widened with the onset of COVID-19. While men and women experienced similar rates of underemployment in 2019 (6.8 percent and 6.9 percent respectively), underemployment rose to 14 percent among men and 16.8 percent among women in 2020.[xviii]

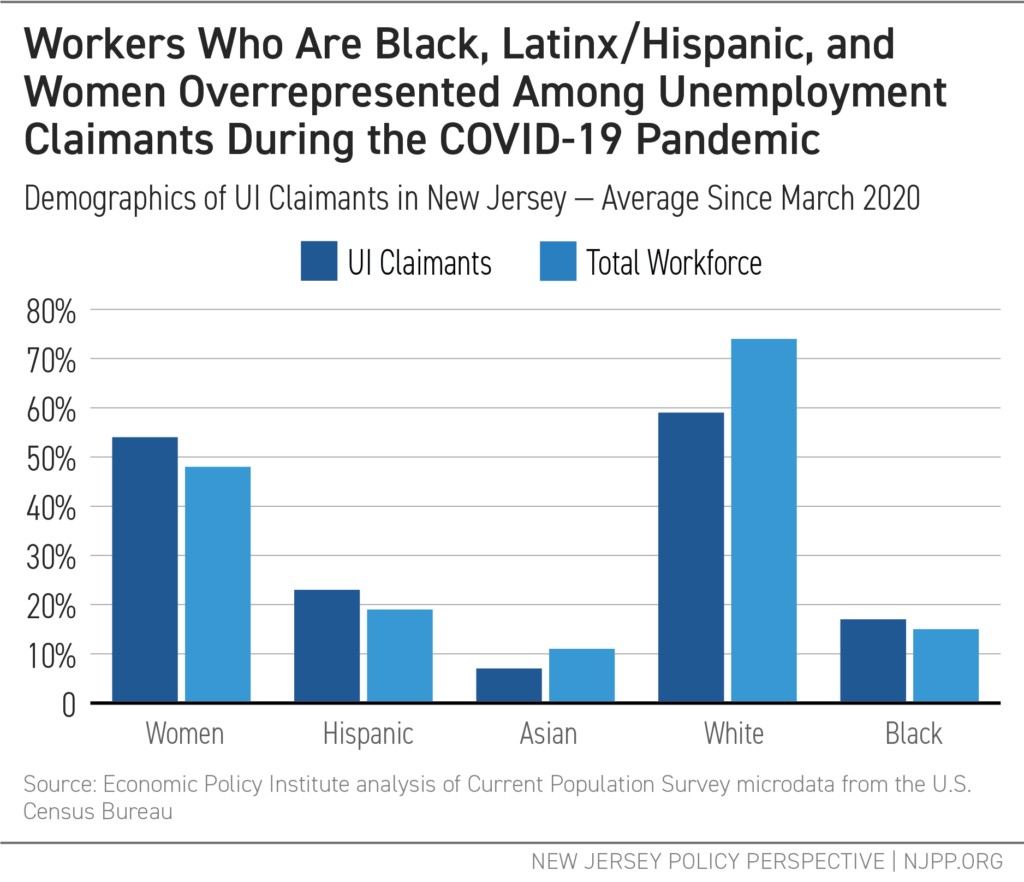

Loss of Unemployment Insurance Disproportionately Harms Women and People of Color

Unemployment insurance claims reflect the racial and gender disparities in employment that have persisted during the pandemic. New Jersey workers who are women, Black, and Hispanic/Latinx make up a disproportionate share of unemployment insurance claims relative to their share of the state’s workforce. For example, while Hispanic/Latinx workers make up 19 percent of New Jersey’s workforce, 23 percent of unemployment claimants in New Jersey are Hispanic/Latinx. Women are also overrepresented among unemployment claimants in New Jersey — while women make up 48 percent of New Jersey’s workforce, 54 percent of unemployment claimants in New Jersey since March 2020, on average, are women.

Worker Protections and Income Supports Critical to Recovery

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted and reinforced the importance of worker protections, good quality jobs, and a strong safety net. Even before the pandemic, wages had been largely stagnant for workers in the lowest paid industries until the recent increase in the state minimum wage.[xix] As a result, many workers earn too little to make ends meet, let alone save for a rainy day. When the health emergency hit, many New Jersey workers who lost their jobs had little or no savings. Coupled with low wages, massive gaps in worker protections and safety net programs continue to leave many New Jersey workers particularly vulnerable to crises.

Among New Jersey residents who were able to stay employed, many continued to earn substandard wages, face unsafe conditions, and lack access to adequate sick days and paid leave. In the absence of federal worker health and safety standards and protections, Governor Murphy issued Executive Order 192 in the fall of 2020, which established health and safety protocols, including guidelines relating to social distancing, face masks, cleaning and disinfecting guidelines, and health checks. The executive order also directed the Department of Labor and Workforce Development to develop a mechanism for receiving complaints and to provide compliance and safety training for employers and employees. Since November 2020, workers in New Jersey have filed over 3,000 complaints against their employers.[xx] Following a subsequent executive order which ended the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency, however, the health and safety protocols outlined in Executive Order 192 are no longer required, even as COVID-19 cases are rising with the growth of the Delta variant.[xxi]

Lack of labor and health and safety standards and enforcement leaves many workers unable to speak out about unsafe conditions without risk of retaliation or loss of income. In addition, inadequate access to paid leave and sick days poses challenges for workers who need to care for loved ones, recover from illness, or receive vaccinations and recover from side effects. Unfortunately, for too many workers, access to health care is also attached to employment. Disparities in economic security and employment create disparate risks of exposure to the virus, and accordingly, may contribute to racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 cases and deaths.[xxii]

Advancing a more inclusive recovery and economy will require not only job growth, but policies that support quality jobs with access to paid leave, sick time, fair scheduling, and adequate wages.

Recommendations for an Inclusive Recovery

An inclusive pandemic recovery will require targeted investments and policies that support the health and economic security of all New Jersey residents. Many of the disparate impacts of COVID-19 outlined in this report are rooted in social and economic injustices, which continue to create barriers for many workers and families. Accordingly, a return to the status quo will only perpetuate these structural inequities.

There are several immediate steps that New Jersey lawmakers can take to improve conditions for workers across the state who have been left behind by existing policies. As some workers lose access to unemployment insurance benefits, and others continue to be excluded from unemployment insurance altogether, improving access to income supports and programs that can help families cover the cost of basic needs, like food, rent, and childcare, is more important than ever. In addition, taking steps to improve worker health safety will improve the wellbeing of workers’ families and communities, and by extension, improve our state’s economic recovery from the current crises.

Fully Fund Pandemic Relief and Income Replacement for Excluded Workers

While most New Jersey residents harmed by the pandemic have been able to turn to unemployment insurance, stimulus payments, and other programs, many workers who have experienced unemployment in New Jersey continue to face financial hardship without relief. New Jersey lawmakers can help address this gap by fully funding the Excluded Workers Fund in order to provide payments and income replacement to all workers who have been excluded from federal relief programs.

Expand Access to Paid Sick Days

With the state’s economic health inextricably linked to its public health, ensuring that workers have access to paid sick days is critical to the state’s recovery. Unfortunately, New Jersey’s current earned sick day law is both insufficient to meet the needs of the current health emergency and burdensome for many workers. New Jersey only requires that employers provide five sick days per year, and employers can require that workers wait 120 days after the first day of work to use sick days. As a result, many workers are unable to take all the time they need to recover from an illness or to get a vaccine without sacrificing income or facing retaliation from their employer. New Jersey can ensure that more workers are able to take sick leave when they need it by increasing the number of paid sick days available to workers, raising awareness about and better enforcing the state’s sick days law, and reducing barriers to taking sick days.

Strengthen Worker Protections

As workers continue to face unsafe conditions and fear retaliation, strengthening worker protections is necessary to fully recover from the health and economic crises. The state should provide clear and enforceable health and safety standards and protocols. In addition, given the threat and reality of retaliation in many workplaces, lawmakers should adopt statewide job protections to prohibit employees from being punished or fired without warning or a good cause. Preventing retaliation for raising concerns about workplace problems, such as health and safety violations, can improve stability and economic security for New Jersey’s workers. Another mechanism for improving conditions for workers is targeted legislation that addresses the unique circumstances of workers in industries rife with worker exploitation and health and safety concerns, including temp work and domestic work.

Raise Substandard Wages

Low wages compromise the well-being and economic security of many New Jersey residents. While New Jersey’s minimum wage law has improved conditions for some workers, many workers, including tipped workers and farmworkers, earn less than the standard minimum wage of $12.00 per hour. In addition, many workers who have been risking their own safety to provide essential services throughout the pandemic earn too little to make ends meet. One mechanism for raising substandard wages is by convening wage boards. Through wage boards, labor representatives, employers, and state labor officials could work together to agree upon fair wage standards for an entire industry.

A Strong Recovery Requires Strong Worker Protections

With the Delta variant on the rise and the threat of additional variants looming, New Jersey’s economic recovery is directly tied to recovery from the health crisis. While steady increases in job numbers provide hope, the quality of jobs is equally important. An inadequate safety net, combined with decades of wage stagnation and declining worker power, leaves many workers with no good options during this challenging time. The termination of key safety net programs and worker protections will cause more workers to be pushed into economic hardship or into jobs with unsafe conditions, low wages, and limited access to sick days and paid leave. A strong and equitable recovery from this crisis will require lawmakers to create supports and protections for workers that match the health and economic conditions of this challenging time.

End Notes

[i] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. 2014 (Updated in 2020). “Introduction to Unemployment Insurance.” https://www.cbpp.org/research/introduction-to-unemployment-insurance

[ii] United States Department of Labor Employment and Training Administration. “Unemployment InsuranceWeekly Claims Data.” Retrieved from https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/claims.asp

[iii] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. 2021. “Policy Basics: Unemployment Insurance”. https://www.cbpp.org/research/economy/unemployment-insurance

[iv] Stettner, Andrew. 2021. “7.5 Million Workers Face Devastating Unemployment Benefits Cliff This Labor Day.” https://tcf.org/content/report/7-5-million-workers-face-devastating-unemployment-benefits-cliff-labor-day/

[v] Stettner, Andrew. 2021. “7.5 Million Workers Face Devastating Unemployment Benefits Cliff This Labor Day.” https://tcf.org/content/report/7-5-million-workers-face-devastating-unemployment-benefits-cliff-labor-day/

[vi] “Governor Murphy Announces $275 Million in Relief for Small Businesses and Individuals Impacted by COVID-19 Public Health Crisis.” https://www.nj.gov/governor/news/news/562021/20210507a.shtml

[vii] Center for Migration Studies. “State-Level Unauthorized Population and Eligible-to-Naturalize Estimates.” http://data.cmsny.org/

[viii] United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. State and Area Employment, Hours, and Earnings. New Jersey – Total Nonfarm. Retrieved from https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/dsrv?sm

[ix] United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. State and Area Employment, Hours, and Earnings. New Jersey – Total Nonfarm. Retrieved from https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/dsrv?sm

[x] United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. State and Area Employment, Hours, and Earnings. https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/SMS34000007000000001?amp%253bdata_tool=XGtable&output_view=data&include_graphs=true

[xi] United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. State and Area Employment Hours, and Earnings. Retrieved from https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/SMS34000007000000001?amp%253bdata_tool=XGtable&output_view=data&include_graphs=true

[xii] Center for Economic Policy and Research. 2020. “A Basic Demographic Profile of Workers in Frontline Industries”. https://cepr.net/a-basic-demographic-profile-of-workers-in-frontline-industries/

[xiii] Economic Policy Institute. “Low-wage, low-hours workers were hit hardest in the COVID-19 recession.” https://www.epi.org/publication/swa-2020-employment-report/

[xiv] United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. Local Area Unemployment Statistics. Retrieved from: https://www.bls.gov/data/

[xv] Opportunity Insights. “Economic Tracker.” Retrieved from https://www.tracktherecovery.org/

[xvi] Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey microdata from the U.S. Census Bureau.

[xvii] Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey microdata from the U.S. Census Bureau

[xviii] Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey microdata from the U.S. Census Bureau

[xix] Economic Policy Institute Analysis of Current Population Survey Microdata from the U.S. Census Bureau

[xx] Yi, Karen. 2021. “NJ Workers Filed Thousands of COVID-19 Complaints Against Their Employers. Here are the Worst Offenders.” Retrieved from https://gothamist.com/news/nj-workers-filed-thousands-covid-19-complaints-against-their-employers-here-are-worst-offenders

[xxi] “Governor Murphy Highlights Aspects of Legislation Allowing for the Termination of the Public Health Emergency Effective as of July 4.” https://www.nj.gov/governor/news/news/562021/20210702c.shtml

[xxii] Yi, Karen. “‘Whole Generations of Fathers Lost As COVID-19 Kills Young Latino Men in NJ.’” Gothamist. https://gothamist.com/news/whole-generations-of-fathers-lost-as-covid-19-kills-young-latino-men-in-nj