Earlier this year, NJPP released a report that found Camden’s publicly funded schools were hiring a teaching workforce that was increasingly white and less experienced.[i] While some of this shift was due to changes in the Camden public school teaching staff, most of the change was due to the growth of charter and renaissance schools in the city.[ii] Yet, New Jersey needs more teachers of color in its ranks, especially in communities with many students of color, as research shows these students benefit from having teachers who look like they do.[iii]

But is Camden unique? Other cities in New Jersey have seen significant growth in charter school enrollments; have they also seen shifts in the racial and ethnic composition of their total teaching workforces? To answer the question, we look at the percentage of Black teachers in other large, urban districts (over 10,000 students) that have a significant charter school presence (where greater than 15 percent of students are enrolled in charter schools).

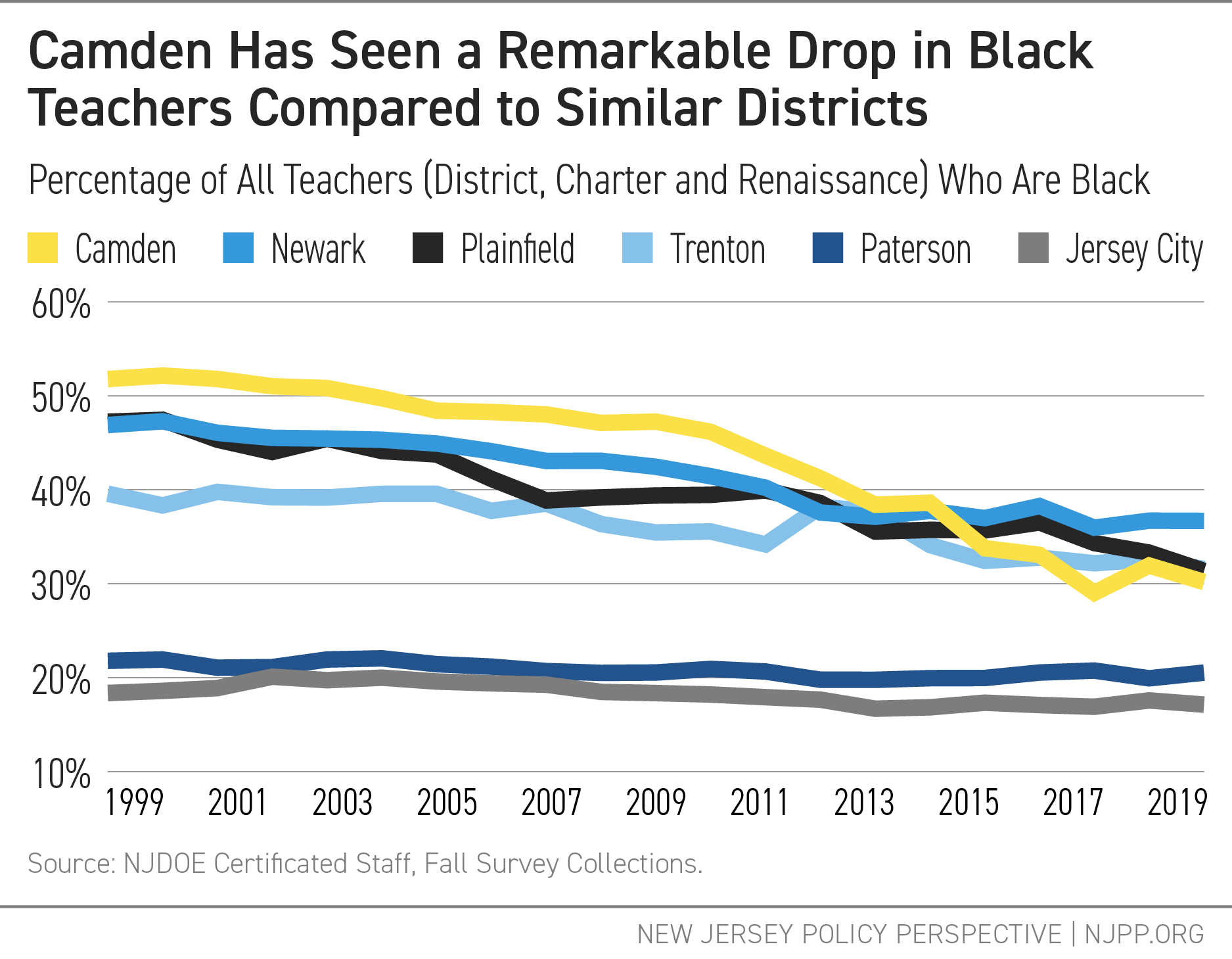

The figure below shows the change in the percentage of Black teachers across a city’s entire teacher workforce: public district, charter, and renaissance combined.

Over the last two decades, Jersey City’s and Newark’s teacher workforce has remained about one-fifth Black; while there has been little change, the proportion of Black teachers was small to begin with. In Newark, Plainfield, and Trenton the proportion of Black teachers has dropped between 8 and 16 percentage points since 1999.

Camden’s decline in Black teachers, however, is greater than any other city’s: a 22 percentage point decrease over the past two decades. What’s especially notable is that Camden was employing a greater percentage of Black teachers than all the comparison districts in 1999; in other words, the district that was hiring the greatest share of Black teachers proportionally has now seen the greatest decline in their numbers.

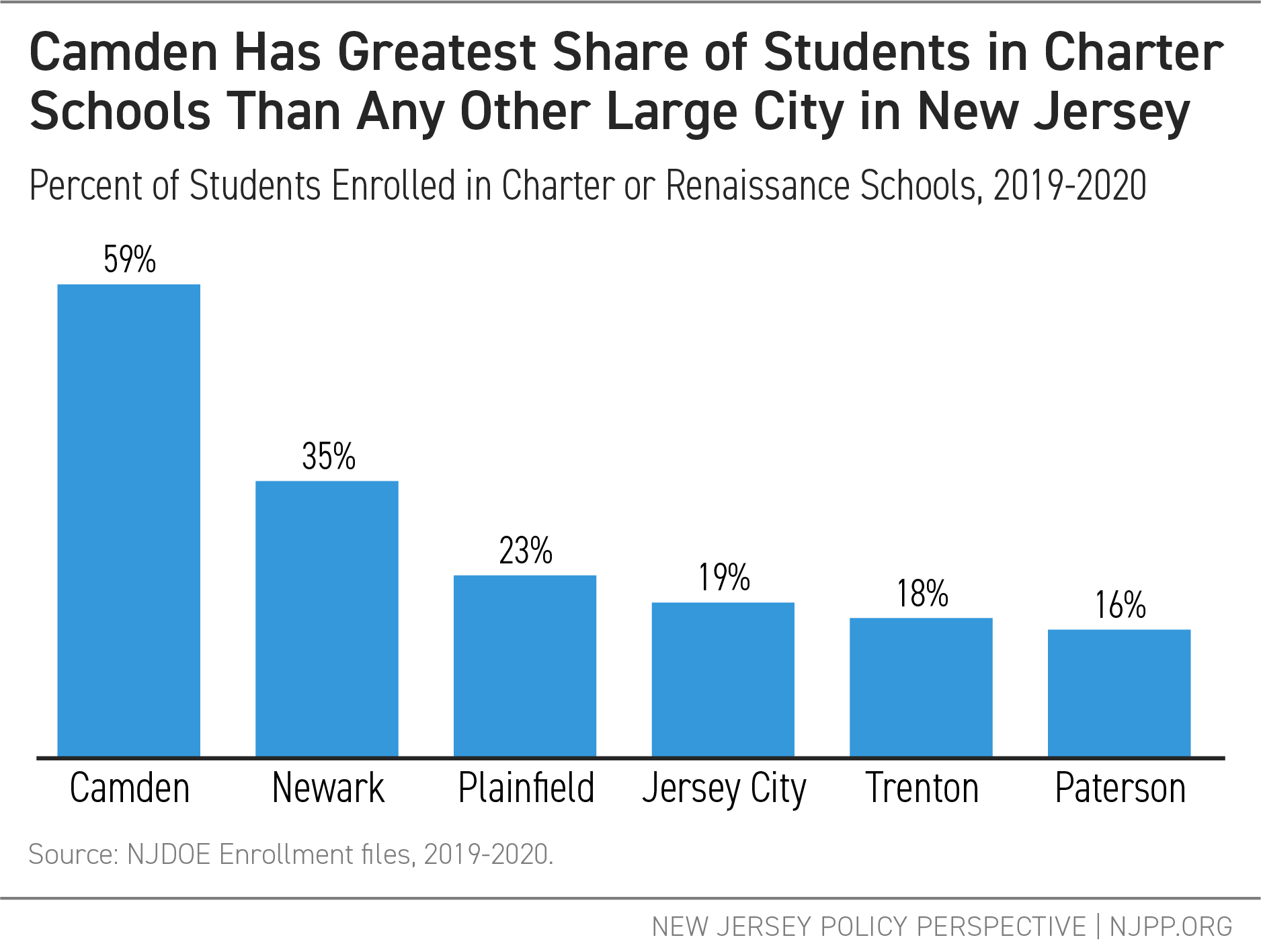

Charter school growth has been largely responsible for the changes in the diversity of Camden’s teacher workforce, as our first report notes. As the chart here shows, Camden has a usually high level of charter proliferation. Other large cities, however, still have significant numbers of students enrolled in charters, yet the racial and ethnic composition of their teacher workforces has not changed as dramatically as Camden’s. Important context to note is that charter schools are publicly funded but operate separately from public school districts: they are authorized by the state and not a local school district, they may cap their enrollments and choose which grade levels to enroll, and many are not subject to collective bargaining agreements, as their staffs are not unionized. Renaissance schools, unique to Camden, are also a type of charter school. The three renaissance schools in Camden are operated by charter management organizations that run charter schools in other cities such as Newark and Philadelphia, PA.

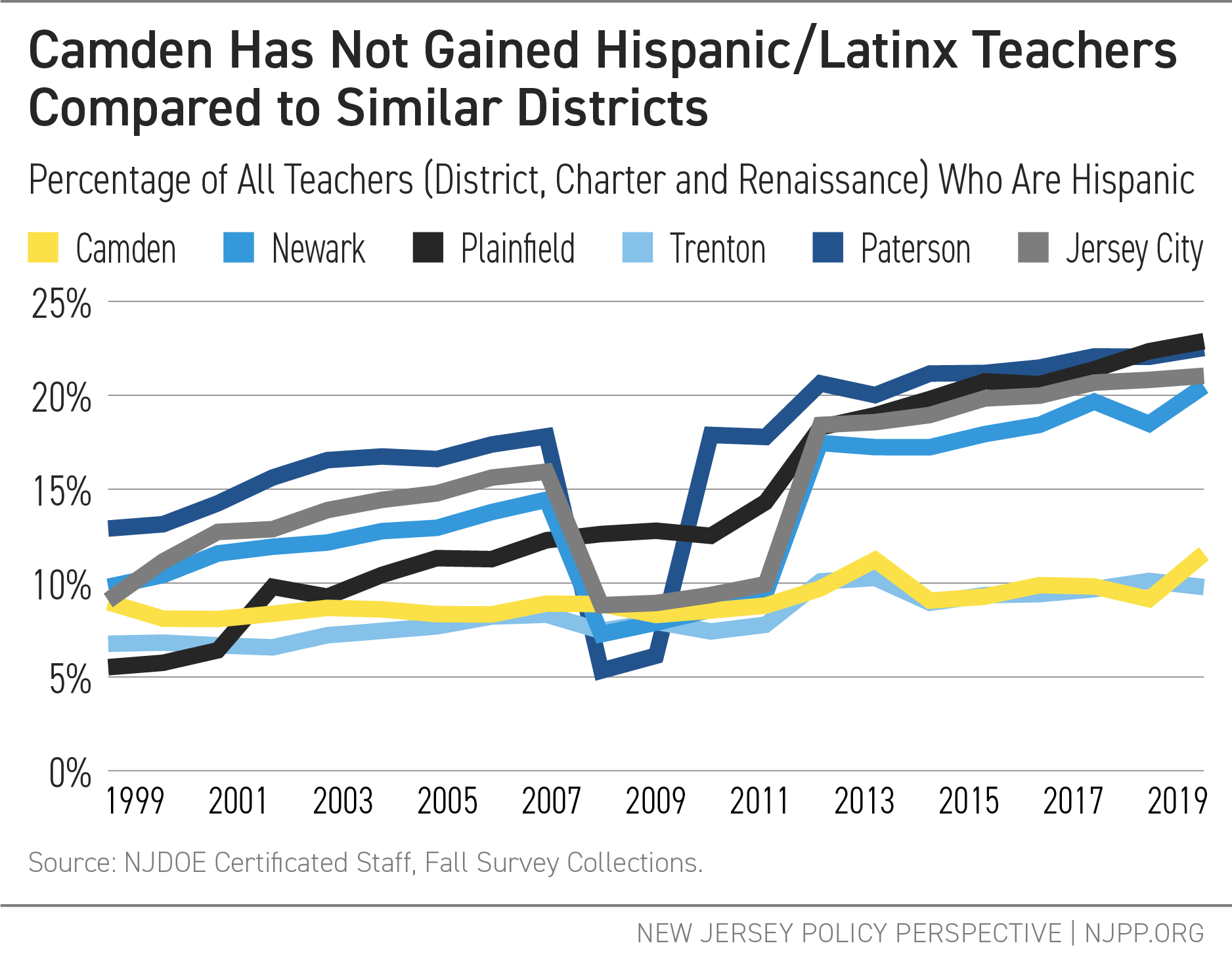

The decline in Black teachers does not necessarily mean there are more white teachers; teachers from other racial and ethnic backgrounds may be replacing Black teachers. The percentage of Hispanic/Latinx teachers, for example, in most other large urban districts (excluding Trenton) has grown over the last twenty years.[iv] But the proportion of Hispanic/Latinx teachers in Camden has remained roughly the same: between 9 and 12 percent over the last two decades. Camden, therefore, has not been replacing its Black teachers with Hispanic/Latinx teachers, even as other districts have.

The data does not reveal whether other large, urban districts in New Jersey would lose more Black teachers if their charter school enrollments rose as high as Camden’s. These other districts, however, have not seen nearly the decrease in Black teachers that Camden has. This suggests state and Camden policymakers could be doing more to recruit and retain Black teachers, even in the face of an increasing charter school presence.

At the same time, the state and other cities should look at Camden as a cautionary tale: simply allowing charters to grow without taking actions to preserve Black teaching jobs may significantly diminish the diversity of their district’s teacher workforce. This overlooked but important aspect of education policy should be acknowledged and addressed as New Jersey continues to reform charter school laws and regulations.

End Notes

[i] Weber, Mark (February 11, 2021). “The ‘Whitening” of Camden’s Teachers.” Trenton, NJ: New Jersey Policy Perspective. https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/the-whitening-of-camdens-teachers/

[ii] Charter and renaissance schools are taxpayer-funded schools that operate separately from school districts, hiring their own teaching and administrative staff.

[iii] Mark Weber (September 9, 2019). “In Brief: New Jersey’s Teacher Workforce, 2019.” Trenton, NJ: New Jersey Policy Perspective. https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/in-brief-new-jerseys-teacher-workforce-2019-diversity-lags-and-wage-gap-persists/

[iv] There is a clear but temporary shift in data reporting for some districts between 2008 and 2012, creating a sharp drop, then a sharp increase, in the percentage of Hispanic teachers. This is likely due to changes in the categorization of race and ethnicity under federal guidelines starting in 2008.