By

Published on Oct 14, 2020 in COVID-19, Health

Health disparities in the COVID-19 pandemic spotlight the long-standing inequities that permeate the health care system. Though the pandemic has been undeniably devastating throughout the country, the impact on Black and Latinx communities outpaces that on other populations.[i] Nationally, Black and Latinx residents have been three times more likely than white residents to contract COVID-19 and nearly twice as likely to die from it.[ii] These patterns are also reflected at the state level. This report examines racial disparities in New Jersey throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and suggests policy solutions to alleviate these problems and build more equitable conditions for the future.

Black and Latinx Cases, Hospitalization Rates, and Mortality Rates Outpace Others

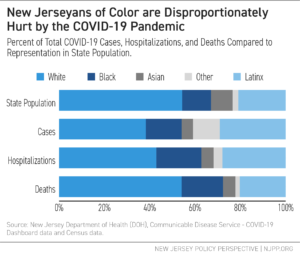

The Garden State’s population, while increasingly diverse, still sees the impact of structural racism in its housing and occupational divides.[iii] Past redlining practices have resulted in the segregation of neighborhoods and schools, with many Black and Latinx families living in densely populated metro areas with segregated school districts.[iv] Residents of color make up over half of employees in essential, or “frontline” industries, including grocery stores and pharmacies; trucking, warehouse, and postal services; cleaning services; public transportation; health care; and child care and social services.[v] These vulnerabilities, in addition to the need for many to commute into New York City or Philadelphia for work, put these residents at greater risk for exposure to the virus. The results of that structural risk are seen in the data, with Black and Latinx populations disproportionately represented in COVID-19 case, hospitalization, and mortality rates.

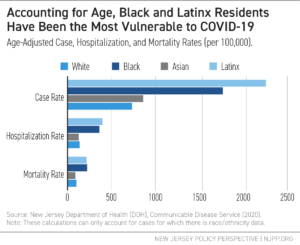

Age-adjusted case, hospitalization, and mortality rates also show that New Jersey’s Black and Latinx residents have suffered directly from the disease at double to triple the rates of the state’s white and Asian residents.[vi] Due to poor socioeconomic conditions and systemic racism in the health care system, Black and Latinx communities often die at younger ages and have proportionally more young residents than white populations. This means that, amongst the elderly, there are regularly more white than Black or Latinx individuals. The elderly are the most vulnerable age group to COVID-19, which is a possible reason that the white death rate is proportionally higher than the case rate — because there are more white, as opposed to Black or Latinx, elderly residents to suffer from age vulnerability. However, Black and Latinx residents are more likely to contract, be hospitalized, and die from COVID-19 than white residents of the same age group. The age-adjusted rates, then, allow us to better compare relatively incomparable populations, by assessing what the rates would look like if the age structures (proportion in each age group) of these populations were the same. In the case of New Jersey, this shows that Black and Latinx residents have been significantly more likely to suffer from COVID-19 in every way than white or Asian residents.

The state data remains consistent with patterns seen at the national level. In the COVIDView Surveillance Summary published weekly by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nationally reported hospitalization rates amongst Latinx, Black, and American Indian or Alaska Native residents are higher than those of white residents in every age group. The highest rates by age group in the national data range from 3.7 (for non-Latinx Black residents, age 65+) to 8.2 (for Latinx residents, ages 18-49 years old) times those of white residents for that age group.[vii]

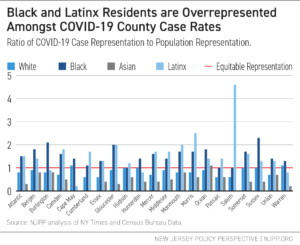

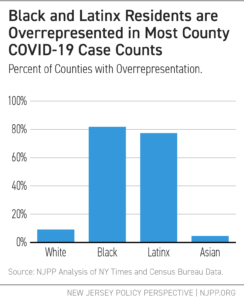

Black and Latinx people are more likely to contract COVID-19 than would be expected based on their representation in most counties. Black residents have been particularly overrepresented amongst cases in Atlantic, Burlington, Camden, Essex, Gloucester, Mercer, Somerset, and Union Counties. This means that, even in places where the outbreak and surge began later and general protective measures were already put in place when the disease arrived, residents of color were still more vulnerable than others; their high numbers of deaths and cases were not just due to initial outbreak conditions. In Salem County, for example, Latinx residents made up approximately 40 percent of cases by the end of May, while only accounting for roughly 9 percent of the county population. This means that Latinx residents are between 4 and 5 times overrepresented in the county case count as compared to their representation in the population.[viii] Like with the state-level data, there is a clear divide between Latinx and Black health outcomes and white and Asian health outcomes.

Addressing racial inequities in health will take more than a quick infusion of money or testing during the public health crisis, however. Success in tackling these inequities will include not only improvements in access and quality in the health care system itself, but improvements in conditions shaped by social determinants of health that exacerbate vulnerabilities to outbreaks, such as inadequate housing,[ix] limited access to nutritious foods,[x] and low-paying jobs in unsafe environments that prove to be essential during historic pandemics.[xi]

Addressing racial inequities in health will take more than a quick infusion of money or testing during the public health crisis, however. Success in tackling these inequities will include not only improvements in access and quality in the health care system itself, but improvements in conditions shaped by social determinants of health that exacerbate vulnerabilities to outbreaks, such as inadequate housing,[ix] limited access to nutritious foods,[x] and low-paying jobs in unsafe environments that prove to be essential during historic pandemics.[xi]

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted these broader trends in socioeconomic vulnerabilities. Residents of color have seen the greatest unemployment rates throughout the crisis in New Jersey, putting them at greater risk for financial insolvency.[xii] In the Household Pulse Survey from the Census Bureau, Black and Latinx households in New Jersey were approximately three times more likely than white households to report not having enough to eat in the past seven days.[xiii] Black and Latinx residents, as well as residents identifying as multiracial, were more likely to report being behind on rental payments than white or Asian residents: Latinx residents were twice as likely as white residents to report this, while Black and multiracial residents were between 3.5 and 4 times more likely to do so.[xiv] Latinx residents were three times more likely than white residents to report lacking health insurance, in addition to being the most likely residents to experience feelings of nervousness, anxiety, and being on edge.[xv] Black residents were twice as likely as white residents to report lacking health insurance;[xvi] they were also most likely (nearly 1.5 times more likely than white residents) to report both delaying medical care and needing medical care for something other than COVID-19, but not getting it, in the past four weeks.[xvii] As a result, there are dual crises: residents of color have a greater likelihood of contracting the virus due to unhealthy conditions beyond their control, while they also face the devastating impact of the virus on long-term health and finances. This will create even greater inequities of health and well-being outcomes in the post-COVID-19 world.[xviii]

Lack of Adequate Planning and Prevention has Led to Greater Suffering

State and local lawmakers’ efforts to address racial disparities and prevent devastation that exacerbates inequities have been inadequate. New Jersey’s county leaders did not anticipate a pandemic sweeping through the state so violently; only Mercer County identified a pandemic as a hazard of concern in mitigation plans in 2018.[xix] Given this, during the early stages of the crisis, counties were less prepared, hospitals were overwhelmed, and, without known treatments and overflowing hospital beds, providers were required to ration treatments, meaning that patients were more likely to die.[xx]

This lack of preparation was not inevitable. In New Jersey, past disease outbreaks have shown that certain counties and populations are regularly vulnerable to these early stages of epidemics.[xxi] With COVID-19, the first case was identified in Bergen County, near New York City, on March 4, 2020.[xxii] The outbreak quickly spread to the neighboring counties outside of New York City, the same counties that have been vulnerable to outbreaks in the past.[xxiii] Of the state’s seven counties with majority communities of color — that is, counties with over 50 percent of the population identifying as Latinx, Asian, Black, Alaska Native, American Indian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, or another race outside of the white population in the 2019 American Community Survey data (Cumberland, Essex, Hudson, Mercer, Middlesex, Passaic, and Union) — five (Essex, Hudson, Middlesex, Passaic, and Union) were among those hit the hardest by the pandemic during its early stages.[xxiv] Even within counties, communities of color suffered more than white populations, as access to resources became a determining factor in the number of cases and deaths, creating disparities between neighboring zip codes.[xxv]

This means that the harms of COVID-19 in New Jersey have been two-fold. First, the counties to initially get hit — and therefore, are most vulnerable to a surge beyond their hospitals’ capacities — were largely communities of color, resulting in many cases and deaths among residents of color. Then, in counties not hit by the early surge, Black and Latinx populations have been more vulnerable, likely due to the effects of structural racism that have created unhealthy environments and living conditions, limited access to care, and discrimination in care.[xxvi]

This lack of planning can be seen in health statistics beyond the COVID-19 data. This is because the toll of COVID-19 comes not only from cases related to the disease itself, but also from its consequences. Excess death data, which compares the deaths counted during a specific time period to average deaths during that period in previous years, can help to show a picture of the true impact of an event by accounting for not only deaths directly from COVID, but also those that may have resulted from the indirect effects of the outbreak, such as depression and other mental health challenges due to hardships or an unwillingness or fear of seeking care for other medical issues.[xxvii]

Like with the confirmed cases data, New Jersey’s most diverse communities have significant representation when examining excess deaths. Essex County, in which approximately 70 percent of residents are people of color, saw nearly 1,900 excess deaths at the peak of the pandemic in April 2020, an approximately 400 percent increase over the average April death count for the county.[xxviii] Essex County has also experienced the highest number of deaths overall from COVID-19, counting 1,901 confirmed deaths as of October 7, 2020. Additionally, there have been an estimated 229 probable COVID deaths in the county that have not been confirmed.[xxix]

While Essex County’s number of excess deaths comes close to its number of confirmed and probable COVID-19 deaths, the hundreds of additional deaths included in the data may be unconfirmed deaths due to COVID-19.[xxx] These can result from lack of access to testing, avoidance of or lack of access to care for other medical issues, or “deaths of despair” — deaths due to drugs, suicide, or alcohol — that can be connected to the stress of the COVID-19 pandemic.[xxxi] Amongst communities of color, deaths both directly from COVID-19 and deaths caused indirectly by the pandemic’s conditions are also exacerbated by “weathering,” the effect on health and well-being of living long term with inequitable socioeconomic conditions.[xxxii]

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic does not end with hospitalizations and deaths, or even with possible unconfirmed deaths or deaths caused indirectly from the pandemic’s conditions. Differences in trust in the medical system across racial groups will cause these disparities to diverge even further. A long history of systematic racism in health care remains fresh for many Black residents, and many still experience this racism today. This has led to a distrust among Black communities, in particular, of doctors, vaccines, and other paths that will be necessary tools in containing the outbreak.[xxxiii] If people most at risk for the virus and long-term damaging effects or death are also more likely than others to either not have access to or to be unwilling to get the vaccine, then disparities will become even greater as the outbreak rages on amongst our most vulnerable populations. The more the virus continues to spread, the more that neighbors, friends, classmates, and co-workers also continue to risk contracting COVID-19, and the worse the long-term economic impact of the pandemic.

The lack of extensive data collection and transparency makes all of the efforts to address issues of inequity and build better preparedness systems more difficult. Lawmakers have been slow to initiate the collection of racial and ethnic data during both COVID-19 and previous public health emergencies, resulting in partial data and a need to try to backtrack in order to add this data to previously collected information.[xxxiv] When data is collected, the categories often used for race and ethnicity, including those used by the New Jersey Department of Health (DOH) cited here, are broad. In being so broad, they do not accurately depict the many varied experiences of residents within each race or Latinx category. They do not, for instance, differentiate between residents identifying as East Asian (such as Japanese) versus South or Southeast Asian (such as Indian). They also do not account for the different experiences of residents who are first-generation immigrants as compared to residents who identify with a racial or ethnic group but have grown up in the United States. This can be an important factor in understanding the full picture of residents’ experiences with racism in the healthcare system and therefore needs to be examined more in-depth than the data currently provides.[xxxv]

Greater Investment in the Future Health of New Jersey is Necessary

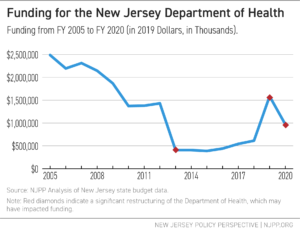

Budget choices reveal lawmakers’ values, especially when choices about access to health programs can literally be the difference between life and death. Overall, funding for DOH has significantly decreased over the past 15 years, standing 61 percent lower than its Fiscal Year (FY) 2005 levels. Funding relative to the size of the population has been reduced from $287.62 per resident in FY 2005 to $178.46 per resident in FY 2019.[xxxvi]

Some of this funding decline was due to structural changes, such as the moving of programs outside of DOH. For instance, the Division of Aging (formerly known as Senior Services) — which funds programs like the Pharmaceutical Assistance to the Aged and Disabled (PAAD) and Senior Gold programs that provide prescription drug benefits to low-income seniors and individuals with disabilities — moved to the Department of Human Services (DHS) in FY 2013.[xxxvii] In addition, the state has not increased funding for DOH to reflect increases in New Jersey’s population.

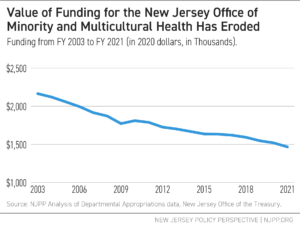

While DHS directs many services related to health (such as Medicaid) and other anti-poverty initiatives that address social determinants of health, the overall decline in direct DOH funding has resulted in diminishing support for many key divisions and programs addressing health inequities. These include the Office of Minority and Multicultural Health as well as the Communicable Disease Service, which are meant to strengthen New Jersey’s health care system and better protect New Jersey residents.

The Office of Minority and Multicultural Health, the mission of which is to “promote health equity for all and reduce health disparities,” has received the same special purpose funding ($1.5 million) from the early 2000s up until the fiscal year 2021 budget, when a slight cut was made in response to the COVID-19 crisis.[xxxviii] Because the funding was maintained at the same dollar amount, the value of those dollars has decreased over the years due to inflation.

Attention given to newer initiatives to address racial disparities, such as the Nurture NJ multi-agency campaign to address New Jersey’s abysmal Black maternal and infant mortality rates, has provided some promise of improvements in the future.[xxxix]These programs cannot be short-lived or one-off promotions, however, to truly impact the long-term health landscape for New Jersey’s populations. In order to both permanently and effectively address racial disparities in health outcomes, New Jersey lawmakers should consider prioritizing the following:

- Build data collection capacity and transparency.

Much of the data presented in this brief does not cover all cases, hospitalizations, or deaths. Some only cover around 50 to 60 percent of cases because racial and ethnic data was not directed to be collected until the end of April, a month after Governor Murphy instituted his stay-at-home order.[xl] The need for this data should not have been a surprise — there were many calls for better collection efforts after the 2009 H1N1 outbreak in the United States, which appear to have gone unheeded.[xli] Without data — and particularly data collected on cases, rather than just during hospitalization or post-mortem — it is impossible to determine how to most effectively and efficiently fund and design programs meant to address racial inequities.A federal initiative to regulate these types of actions across states would produce more uniform data and a clearer picture than current efforts, since states have differing practices in both the decisions to collect data and how they collect the data.[xlii] However, until federal-level initiatives are pursued, New Jersey can take its own steps to become a leader in these efforts. Regulations that automatically trigger this data collection during crises and permanent directives to collect this data would move the state forward in better understanding the consequences of outbreaks like COVID-19. Additionally, greater efforts to coordinate and support systematic population health work in the state is needed: New Jersey is currently one of only 15 states without a public health institute or participation in the National Network of Public Health Institutes.[xliii] - Require regular state health racial equity impact assessments for policy proposals.

In addition to greater data transparency during crises, New Jersey should require systematic analysis of the racial impacts of policy proposals. This would both aid in providing a picture of the long-term impact a policy would have on New Jersey’s population, as well as develop a stronger understanding of policy designs that work.[xliv] Having improved data collection efforts, as mentioned in the section above, is crucial for this work. - Increase support for initiatives that improve trust in the medical system.

While cultural competency training will aid in the communication between doctors and patients and therefore should be continued, it does not guarantee overall greater health outcomes unless residents of the at-risk populations come to a medical professional in the first place.[xlv] Programs that work to understand the causes of distrust and identify trusted sources of information can help to create better systems for disseminating facts about medical care and encourage take-up. Increased funding and support for New Jersey’s Office of Minority and Multicultural Health, initially established in 1991, can provide a foundation for these efforts.[xlvi] - Encourage policies that diversify the medical field and improve access to culturally sensitive resources.

While steps have been made in recent years to bring more diversity to medical education and, in turn, the medical field, even more can be done to encourage the building of a medical profession that reflects the population it is serving.[xlvii]Continuing to build programs that provide support for medical professionals who come from vulnerable populations, better encourage practice in areas of greatest need, and remove barriers to providers and services to improve cultural competence of the available resources, will be necessary. New Jersey has recently taken steps in this direction by working to improve access to doula services and removing barriers to professional licenses for immigrant populations.[xlviii] The state should continue in this direction by supporting initiatives focused on greater diversity in the medical field, such as Graduate Medical Education (GME) programs, and by exploring the creation of programs that provide financial support for those serving in areas of critical need.[xlix] - Build racial impact results into future public health crisis preparedness plans.

While the current New Jersey preparedness plan does provide an in-depth look into the possible severity of an outbreak, its economic costs, and environmental and structural factors that may exacerbate certain types of outbreaks, there is no discussion of the fact that certain racial and ethnic groups are more subject to those factors than others, and that the combined impact of the inequities can exacerbate the poor outcomes even further.[l]

Building on these efforts with additional policies that address housing, food insecurity, schooling, workers’ safety, and other areas that impact health will further lessen the inequities in health outcomes that we see in New Jersey. While New Jersey’s challenges in these areas seem daunting, systematic investment in programs that promote equity will lead to healthier lives for all — both during normal times and especially during future health crises.

[i] This brief refers to residents who identify as having ethnic roots in Spain or Latin America with the term “Latinx.” While this term is not used by all residents identifying with this ethnicity (see Noe-Bustamante, Luis, Lauren Mora, and Mark Hugo Lopez (2020). “About One-in-Four U.S. Hispanics Have Heard of Latinx, but Just 3% Use It.” Pew Research Center. Online: https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2020/08/11/about-one-in-four-u-s-hispanics-have-heard-of-latinx-but-just-3-use-it/), this term is more inclusive of all populations with this ethnic identity, including those who may not identify as native Spanish speakers. Also, utilizing “Latinx” rather than “Latino” or “Latina” is more gender-inclusive. All of these considerations help to create more inclusivity for the population considered here, something that is particularly important in addressing structural racism in health care, which does not, in many ways, differentiate between a first-generation immigrant and later generations with these familial roots.

[ii] Oppel Jr., Richard A., Robert Gebeloff, K.K. Rebecca Lai, Will Wright, and Mitch Smith (2020). “The Fullest Look Yet at the Racial Inequity of Coronavirus.” New York Times. 5 July 2020. Online: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/05/us/coronavirus-latinos-african-americans-cdc-data.html

[iii] Raychaudhuri, Disha (2020). “N.J. is more diverse than ever. See how your town has changed.” NJ Advance Media for NJ.com. 19 February 2020. Online: https://www.nj.com/data/2020/02/nj-is-more-diverse-than-ever-see-how-your-town-has-changed.html

[iv] Orfield, Gary, Jongyeon Ee, and Ryan Coughlann (2017). “New Jersey’s Segregated Schools: Trends and Paths Forward.” UCLA: The Civil Rights Project. November 2017. Online: https://www.civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/new-jerseys-segregated-schools-trends-and-paths-forward/New-Jersey-report-final-110917.pdf?_ga=2.105008256.2029930253.1598600934-536607244.1597420044; Petenko, Erin, and Disha Raychaudhuri (2018). “Why Minorities in N.J. are More Likely to be Denied Mortgages, Explained.” NJ.com. Posted 16 February 2018. Updated 30 January 2019. Online: https://www.nj.com/data/2018/02/modern-day_redlining_how_some_nj_residents_are_bei.html

[v] Center for Economic and Policy Research (2020). “A Basic Demographic Profile of Workers in Frontline Industries.” 7 April 2020. Online: https://cepr.net/a-basic-demographic-profile-of-workers-in-frontline-industries/. State-level data available in linked spreadsheet.

[vi] An important note to make about all this data from the Department of Health is that the categories for race and ethnicity are broad and, in being so broad, do not accurately depict the many varied experiences of residents within each race or Latinx category. This can be an important factor in understanding the full picture of residents’ experiences with racism in the healthcare system and therefore needs to be examined more in-depth than the data currently provides.

[vii] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). COVIDView. Weekly Summary for Week 39, ending September 26, 2020. Online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/covidview/index.html. Hospitalization rates for each age group can be found on page 10.

[viii] Salem County’s first confirmed COVID-19 case was reported on March 21, 2020, approximately 17 days after officials confirmed the first case in New Jersey. This was also the day that Governor Murphy announced the state lockdown of all non-essential businesses. See Salem County Department of Health and Human Services (2020). “Salem County Health Department Confirms First Positive Case of Coronavirus.” 21 March 2020. Online: https://health.salemcountynj.gov/salem-county-health-department-confirms-first-positive-case-of-coronavirus/; Erminio, Vinessa (2020). “Coronavirus in New Jersey: A Timeline of the Outbreak.” NJ Advance Media for NJ.com. Last updated on 12 June 2020. Online: https://www.nj.com/coronavirus/2020/03/coronavirus-in-new-jersey-a-timeline-of-the-outbreak.html

[ix] Taylor, Lauren (2018). "Housing and Health: An Overview of the Literature." Health Affairs Health Policy Brief 10. Online: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20180313.396577/full/

[x] Gundersen, Craig, and James P. Ziliak (2015). "Food Insecurity and Health Outcomes." Health Affairs 34 (11): 1830-1839. Online: https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0645

[xi] McCormack, Grace, Christopher Avery, Ariella Kahn-Lang Spitzer, and Amitabh Chandra (2020). Economic Vulnerability of Households With Essential Workers. JAMA. 2020;324(4):388–390. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.11366. Online: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2767630; Yearby, Ruqaiijah, and Seema Mohapatra (2020). "Law, Structural Racism, and the COVID-19 Pandemic." Journal of Law and the Biosciences (Forthcoming). No. 2020-8. Online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3612824

[xii] Kapahi, Vineeta (2020). “Labor Day Snapshot: How New Jersey Can Honor Workers and Improve Economic Security.” New Jersey Policy Perspective. 7 September 2020. Online: https://www.njpp.org/reports/labor-day-snapshot-how-new-jersey-can-honor-workers-and-improve-economic-security

[xiii] U.S. Census Bureau (2020). Week 15 Household Pulse Survey: September 16-28. “Food Table 2b. Food Sufficiency for Households, in the Last 7 Days, by Select Characteristics: New Jersey.” https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/hhp/hhp15.html At the time of writing, this was the most recent release.

[xiv] U.S. Census Bureau (2020). Week 15 Household Pulse Survey: September 16-28. “Housing Table 1b. Last Month’s Payment Status for Renter-Occupied Housing Units, by Select Characteristics: New Jersey” https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/hhp/hhp15.html At the time of writing, this was the most recent release.

[xv] U.S. Census Bureau (2020). Week 15 Household Pulse Survey: September 16-28. “Health Table 3. Current Health Insurance Status, by Select Characteristics: New Jersey” and “Health Table 2a. Symptoms of Anxiety Experienced in the Last 7 days, by Select Characteristics: New Jersey.”https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/hhp/hhp15.html At the time of writing, this was the most recent release.

[xvi] U.S. Census Bureau (2020). Week 15 Household Pulse Survey: September 16-28. “Health Table 3. Current Health Insurance Status, by Select Characteristics: New Jersey.” https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/hhp/hhp15.html At the time of writing, this was the most recent release.

[xvii] U.S. Census Bureau (2020). Week 15 Household Pulse Survey: September 16-28. “Health Table 1. Coronavirus Pandemic Related Problems with Access to Medical Care, in Last 4 weeks, by Select Characteristics: New Jersey.” https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/hhp/hhp15.html At the time of writing, this was the most recent release.

[xviii] Tolbert, Jennifer Kendal Orgera, Natalie Singer, and Anthony Damico (2020). “Communities of Color at Higher Risk for Health and Economic Challenges due to COVID-19.” Kaiser Family Foundation. 7 April 2020. Online: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/communities-of-color-at-higher-risk-for-health-and-economic-challenges-due-to-covid-19/

[xix] New Jersey Office of Emergency Management (2018). “5.1 Identification of Hazards.” 2019 New Jersey State Hazard Mitigation Plan. Online: http://ready.nj.gov/mitigation/2019-mitigation-plan.shtml Specific chapter: http://ready.nj.gov/mitigation/pdf/2019/mit2019_section5-1_Id_Hazards.pdf. Pg. 5.

[xx] Cavallo, Joseph J., Daniel A. Donoho, and Howard P. Forman (2020). "Hospital Capacity and Operations in the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic—Planning for the Nth Patient." In JAMA Health Forum 1 (3): e200345-e200345. American Medical Association. Online: https://jamanetwork.com/channels/health-forum/fullarticle/2763353; Some groups worked to build tools for building better hospital surge capacity as the pandemic developed. See, for example: Abir, Mahshid, Christopher Nelson, Edward W. Chan, Hamad Al-Ibrahim, Christina Cutter, Karishma Patel, and Andy Bogart (2020). “Critical Care Surge Response Strategies for the 2020 COVID-19 Outbreak in the United States.” Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. Online: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA164-1.html. See also New Jersey’s response to the surge: New Jersey Department of Health (2020). “Allocation of Critical Care Resources During a Public Health Emergency.” 11 April 2020. Online: https://nj.gov/health/legal/covid19/FinalAllocationPolicy4.11.20v2%20.pdf

[xxi] Kaulessar, Ricardo (2018). “100 years ago, Spanish flu pandemic brought dread to New Jersey.” NorthJersey.com. Online: https://www.northjersey.com/story/news/local/2018/10/09/1918-spanish-flu-pandemic-killed-thousands-new-jersey/1222214002/; Influenza Encyclopedia (n.d.) “Newark, New Jersey.” Published by University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing and University of Michigan Library. Online: https://www.influenzaarchive.org/cities/city-newark.html; New Jersey Office of Emergency Management (2018). “5.21 Pandemic.” 2019 New Jersey State Hazard Mitigation Plan. Online: http://ready.nj.gov/mitigation/2019-mitigation-plan.shtml Specific chapter: http://ready.nj.gov/mitigation/pdf/2019/mit2019_section5-21_Pandemics.pdf

[xxii] Office of Governor Phil Murphy (2020). “Governor Murphy, Acting Governor Oliver, and Commissioner Persichilli Announce First Presumptive Positive Case of Novel Coronavirus in New Jersey.” 4 March 2020. Online: https://www.nj.gov/governor/news/news/562020/20200304e.shtml

[xxiii] Kaulessar, Ricardo (2018). “100 years ago, Spanish flu pandemic brought dread to New Jersey.” NorthJersey.com. Online: https://www.northjersey.com/story/news/local/2018/10/09/1918-spanish-flu-pandemic-killed-thousands-new-jersey/1222214002/; Influenza Encyclopedia (n.d.) “Newark, New Jersey.” Published by University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing and University of Michigan Library. Online: https://www.influenzaarchive.org/cities/city-newark.html; New Jersey Office of Emergency Management (2018). “5.21 Pandemic.” 2019 New Jersey State Hazard Mitigation Plan. Online: http://ready.nj.gov/mitigation/2019-mitigation-plan.shtml Specific chapter: http://ready.nj.gov/mitigation/pdf/2019/mit2019_section5-21_Pandemics.pdf

[xxiv] NJPP Analysis of New Jersey Department of Health (DOH), Communicable Disease Service - COVID-19 Dashboard data and Census data. DOH data online at: https://covid19.nj.gov/. Estimated population data found through the American Community Survey through the Census Bureau. 2019 1-Year Estimates. Table DP05, Demographic and Housing Estimates. This can be found online at: https://data.census.gov

[xxv] Balcerzak, Ashley and Stacey Barchenger (2020). “COVID-19 in your ZIP code: Race, income can double your chance of getting sick in NJ.” NorthJersey.com. 13 July 2020. Online: https://www.northjersey.com/story/news/coronavirus/2020/07/13/coronavirus-nj-race-income-can-double-your-chance-getting-sick/5404947002/

[xxvi] Rubin-Miller, Lily Christopher Alban, Samantha Artiga, and Sean Sullivan (2020). “COVID-19 Racial Disparities in Testing, Infection, Hospitalization, and Death: Analysis of Epic Patient Data.” Kaiser Family Foundation. 16 September 2020. Online: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/covid-19-racial-disparities-testing-infection-hospitalization-death-analysis-epic-patient-data/

[xxvii] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). “Excess Deaths Associated with COVID-19.” Online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/covid19/excess_deaths.htm

[xxviii] NJPP Analysis of Census Bureau data. American Community Survey, 2019 1-Year Estimates. Table DP05, Demographic and Housing Estimates. Online: https://data.census.gov

[xxix] New Jersey Department of Health, Communicable Disease Service (2020). COVID-19 Dashboard. Online: https://covid19.nj.gov/. Accessed 7 October 2020. Probable deaths are updated every week, with the latest update on 29 September 2020.

[xxx] It is important to note here that the excess deaths data only covers up until July, and so does not total deaths up until October as the COVID deaths update includes. This means that the total will likely go up for the number of excess deaths, though the later months were not the peak months of the pandemic.

[xxxi] Petterson, Steve et al (2020). “Projected Deaths of Despair During the Coronavirus Recession,” Well Being Trust. 8 May 2020. WellBeingTrust.org. Online: https://wellbeingtrust.org/areas-of-focus/policy-and-advocacy/reports/projected-deaths-of-despair-during-covid-19/

[xxxii] Forde, Allana T., Danielle M. Crookes, Shakira F. Suglia, and Ryan T. Demmer (2019). "The weathering hypothesis as an explanation for racial disparities in health: a systematic review." Annals of epidemiology 33: 1-18.

[xxxiii] Gramlich, John and Cary Funk (2020). “Black Americans Face Higher COVID-19 Risks, are More Hesitant to Trust Medical Scientists, Get Vaccinated.” Pew Research Center. 4 June 2020. Online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/06/04/black-americans-face-higher-covid-19-risks-are-more-hesitant-to-trust-medical-scientists-get-vaccinated/

[xxxiv] Kim, Soo Rin and Matthew Vann (2020). “Many States Are Reporting Race Data For Only Some COVID-19 Cases And Deaths.” FiveThirtyEight. 7 May 2020. Online: https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/many-states-are-reporting-race-data-for-only-some-covid-19-cases-and-deaths/; National Academy for State Health Policy (2020). “How States Collect Data, Report, and Act on COVID-19 Racial and Ethnic Disparities.” Online: https://www.nashp.org/how-states-report-covid-19-data-by-race-and-ethnicity/

[xxxv] Hummer, Robert A. and Iliya Gutin (2018). "Racial/ethnic and Nativity Disparities in the Health of Older US Men and Women." In Future Directions for the Demography of Aging: Proceedings of a Workshop. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, Washington, DC. Pages 31-66; Enchautegui, María E. (2014). “Immigrant Youth Outcomes: Patterns by Generation and Race and Ethnicity.” Urban Institute. Online: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/22991/413239-Immigrant-Youth-Outcomes-Patterns-by-Generation-and-Race-and-Ethnicity.PDF; Teruya, Stacey A. and Shahrzad Bazargan-Hejazi (2013). "The Immigrant and Hispanic Paradoxes: A Systematic Review of Their Predictions and Effects." Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 35 (4): 486-509.

[xxxvi] Calculated using NJPP analysis of Budget Data and Census Data from 2019 estimates (latest available). Intercensal data tables can be found at: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/intercensal-2000-2010-state.html. Data estimates for the 2019 population can be found at: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/NJ. Budget information can be found at: https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/legislativepub/finance.asp

[xxxvii] This is now titled the “Division of Aging Services.”

[xxxviii] New Jersey Department of Health, Office of Minority and Multicultural Health (2020). “About Us.” Last Reviewed: 11/23/2018. Online: http://www.nj.gov/health/ommh/about-us; Budget analysis completed by author using Departmental Appropriations information on the New Jersey Office of Management and Budget (OMB) website.

[xxxix] Office of Governor Phil Murphy. “Nurture NJ.” Online: https://www.nj.gov/governor/admin/fl/nurturenj.shtml

[xl] Office of Governor Phil Murphy. “Governor Murphy Announces Actions to Require Reporting of COVID-19 Demographic Data.” 22 April 2020. Online: https://nj.gov/governor/news/news/562020/approved/20200422b.shtml

[xli] Gibbons, Ann (2020). “How can We Save Black and Brown Lives During a Pandemic? Data from Past Studies can Point the Way.” Science. 10 April 2020. Online: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/04/how-can-we-save-black-and-brown-lives-during-pandemic-data-past-studies-can-point-way

[xlii] National Academy for State Health Policy (2020). “How States Collect Data, Report, and Act on COVID-19 Racial and Ethnic Disparities.” Online: https://www.nashp.org/how-states-report-covid-19-data-by-race-and-ethnicity/

[xliii] National Network of Public Health Institutes (2020). Website: https://nnphi.org/about-nnphi/. Last accessed: 9 September 2020.

[xliv] Race Forward (n.d.). Racial Equity Impact Assessment Toolkit. Online: https://www.raceforward.org/practice/tools/racial-equity-impact-assessment-toolkit; Center for the Study of Social Policy (2018). “Racial Equity Impact Assessment.” Online: https://cssp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Race-Equity-Impact-Assessment-Tool.pdf

[xlv] County Health Rankings & Roadmaps, a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Program (2020). “Cultural Competence Training for Health Care Professionals.” Updated 27 January 2020. Online: https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/take-action-to-improve-health/what-works-for-health/strategies/cultural-competence-training-for-health-care-professionals

[xlvi] New Jersey Department of Health. Office of Minority and Multicultural Health. Online: https://www.nj.gov/health/ommh/

[xlvii] Boatright, Dowin H., Elizabeth A. Samuels, Laura Cramer, Jeremiah Cross, Mayur Desai, Darin Latimore, and Cary P. Gross (2018). "Association between the Liaison Committee on Medical Education’s Diversity Standards and Changes in Percentage of Medical Student Sex, Race, and Ethnicity." JAMA 320 (21): 2267-2269.

[xlviii] Office of Governor Phil Murphy (2020). “Governor Murphy Signs Legislative Package to Combat New Jersey’s Maternal and Infant Health Crisis.” 8 May 2019. Online: https://www.nj.gov/governor/news/news/562019/20190508a.shtml; Office of Governor Phil Murphy (2020). “Governor Murphy Signs Legislation Expanding Access to Professional and Occupational Licenses.” 1 September 2020. Online: https://www.nj.gov/governor/news/news/562020/approved/20200901c.shtml

[xlix] A good example of these efforts is the Washington Health Corps, established in 2019. See information here: https://wsac.wa.gov/washington-health-corps

[l] New Jersey Office of Emergency Management (2018). “5.21 Pandemic.” 2019 New Jersey State Hazard Mitigation Plan. Online: http://ready.nj.gov/mitigation/2019-mitigation-plan.shtml Specific chapter: http://ready.nj.gov/mitigation/pdf/2019/mit2019_section5-21_Pandemics.pdf